|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51:

359-365 |

|

INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Autism Spectrum

Disorder (INDT-ASD): Development and Validation

|

|

Monica Juneja, Devendra Mishra, Paul SS Russell,

Sheffali Gulati, Vaishali Deshmukh, Poma Tudu, Rajesh Sagar, Donald

Silberberg, Vinod K Bhutani, Jennifer M Pinto, Maureen Durkin, Ravindra

M Pandey, MKC Nair, Narendra K Arora and INCLEN Study Group *

From the INCLEN Trust International, New Delhi,

India.

Correspondence to: Dr Narendra K Arora, Executive

Director, The INCLEN TRUST International, F1/5, Okhla Industrial Area,

Phase-1, New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

*INCLEN STUDY GROUP: Core Group: Alok

Thakkar, Arun Singh, Gautam Bir Singh, Manju Mehta, Manoja K Das,

Nandita Babu, Praveen Suman, Ramesh Konanki, Rohit Saxena, Satinder

Aneja, Savita Sapra, Sharmila Mukherjee, Sunanda K. Reddy, Tanuj Dada.

Extended Group: A.K Niswade, Archisman Mohapatra, Arti Maria,

Atul Prasad, B.C Das, Bhadresh Vyas, G.V.S Murthy, Gourie M. Devi,

Harikumaran Nair, J.C Gupta, K.K Handa, Leena Sumaraj, Madhuri Kulkarni,

Muneer Masoodi, Poonam Natrajan, Rashmi Kumar, Rashna Dass, Rema Devi,

Sandeep Bavdekar, Santosh Mohanty, Saradha Suresh, Shobha Sharma,

Sujatha S. Thyagu, Sunil Karande, T.D Sharma, Vinod Aggarwal, Zia

Chaudhuri.

Received: April 03, 2013;

Initial Review: May 21, 2013;

Accepted: February 15, 2014.

|

Objective: To develop and validate INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Autism

Spectrum Disorder (INDT-ASD).

Design: Diagnostic test evaluation by cross

sectional design

Setting: Four tertiary pediatric neurology

centers in Delhi and Thiruvanthapuram, India.

Methods: Children aged 2-9 years were enrolled in

the study. INDT-ASD and Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) were

administered in a randomly decided sequence by trained psychologist,

followed by an expert evaluation by DSM-IV TR diagnostic criteria (gold

standard).

Main outcome measures: Psychometric parameters of

diagnostic accuracy, validity (construct, criterion and convergent) and

internal consistency.

Results: 154 children (110 boys, mean age 64.2

mo) were enrolled. The overall diagnostic accuracy (AUC=0.97, 95% CI

0.93, 0.99; P<0.001) and validity (sensitivity 98%, specificity

95%, positive predictive value 91%, negative predictive value 99%) of

INDT-ASD for Autism spectrum disorder were high, taking expert diagnosis

using DSM-IV-TR as gold standard. The concordance rate between

the INDT-ASD and expert diagnosis for ‘ASD group’ was 82.52% [Cohen’s

k=0.89;

95% CI (0.82, 0.97); P=0.001]. The internal consistency of

INDT-ASD was 0.96. The convergent validity with CARS (r = 0.73, P=

0.001) and divergent validity with Binet-Kamat Test of intelligence (r =

-0.37; P=0.004) were significantly high. INDT-ASD has a 4-factor

structure explaining 85.3% of the variance.

Conclusion: INDT-ASD has high diagnostic

accuracy, adequate content validity, good internal consistency high

criterion validity and high to moderate convergent validity and 4-factor

construct validity for diagnosis of Autistm spectrum disorder.

Keywords: Childhood; Neuro developmental disorders; Resource

limited settings; Childhood austism rating scale; Pervasive

developmental disorders.

|

|

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is widely

recognized for many decades, yet there are no definitive or universally

accepted diagnostic criteria. [1]. Most diagnostic systems and measures

consider ASD to be a 3-symptom cluster disorder with varying severity

and etiology. This is reflected in the diagnostic systems of Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders- IV Text Revision (DSM-IV TR)

and International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10), as well as the

various measures that evolved from them [2,3]. However, the field trials

of the draft version of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders-5 (DSM-5) have supported a 2-symptom cluster model [4,5] of

varying severity.

The construct, core and behavioral symptoms as well

as the reliability of the diagnosis of ASD in diverse socio-cultural

settings using the available tools have been problematic. In addition to

the evolving construct of ASD globally, the timing of the presentation

of this group of disorders [6] and racial differences have been

documented to bring about variations in the core symptoms and associated

behavioral features [7]. In multi-centric studies, the diagnostic

distinctions among sub-categories of ASD has been unreliable across

centers even while using standard diagnostic instruments, supporting a

shift from a categorical to dimensional approach in the diagnosis of ASD

[8]. The use of detailed and explicit appropriateness criteria has

significantly enhanced the diagnostic yield in other medical disciplines

[9]. Furthermore, currently available diagnostic instruments for ASD are

patented [10,11], not available in different Indian languages, and fee

is to be paid each time the instrument is used. To overcome several of

these limitations, INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Autism Spectrum Disorder

(INDT-ASD) was developed for identification and diagnosis of ASD using

appropriateness criteria developed for Indian context.

Methods

Development of Appropriateness Criteria and Instrument

A team of 49 national experts from different parts of

India and six international experts (pediatricians, child psychiatrists,

pediatric neurologists, epidemiologist, pediatric

otorhinolanringologists, clinical psychologists, special educators,

specialist nurses, speech therapist, occupational therapists and social

scientists) developed the appropriateness criteria and tool over three

rounds of 2-day workshop in 2006-2007. During this process, the clinical

criteria for ASD as presented in the ICD-10, DSM-IV TR Autism Diagnostic

Observation Schedule (ADOS), Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS),

Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS), Modified Checklist for Autism in

Toddlers (M-CHAT) and clinicians’ views on the construct of ASD were

reviewed. Pools of items were selected by the panel using the modified

Delphi technique [12]. From the pool of items, the symptoms were

rank-ordered by the panel members, and further reduced using endorsement

rate approach [13].

The construct and its sub-construct were adapted for

its appropriateness in the Indian cultural context and converted into

symptoms clusters for the clinicians and psychologists to rate during

the diagnostic workup. The tool was named as INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for

ASD (INDT-ASD). The tool has two sections: Section A has 29

symptoms/items and Section B contains 12 questions corresponding to B

and C domains of DSM-IV-TR, time of onset, duration of symptoms, score

and diagnostic algorithm. It takes approximately 45-60 minutes to

administer the instrument and score. A trichotomous endorsement choice

(‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unsure/not applicable’) is given to the assessor/

interviewer. In addition, the clinician/psychologist has to make

behavioral observations on the child and score the item as well. For any

discrepancy in parental response and interviewer’s assessment, it is

indicated for each question whether parental response or assessor’s

observation should take precedence. Each symptom/item is given a score

of ‘1’ for ‘Yes’ and ‘0’ for ‘No’ or ‘unsure/not applicable’. Presence

of ³ 6

symptoms/item (or score of ³

6), with at least two symptom/item each from impaired communication and

restricted repetitive pattern of behavior, is used to diagnose ASD [Web

Appendix I].

The instrument was first developed in English, and

forward and backward translated to Hindi and Malayalam by two teams with

two independent, bilingual translators in each, to achieve the proximity

of the source and target versions. This instrument was piloted (first

pilot psychometric evaluation round, described below). Based on the

feedback, the instrument was modified in Hindi version and then forward

translated to English, Malayalam and six additional Indian languages (Odia,

Konkani, Urdu, Khasi, Gujarati and Telugu) and backward translated

in a similar manner.

Psychometric evaluation

The first round of psychometric (pilot) testing for

INDT-ASD was done with 266 children at two sites (New Delhi-178 and

Thiruvananthapuram-88). These included 81 children of ASD, 120 with

other neuro-developmental disorders (NDDs) and 65 with typical

development. However, as the ability of INDT-ASD to differentiate autism

from other NDDs (specificity 69%) and the agreement with CARS [14] was

moderate (kappa=0.69), further training and modifications in translation

(12 items), item changes (3 items) and reframing (7 items with new

examples) was done.

In the second round, psychometric (field) testing of

the INDT-ASD was conducted in four public sector tertiary-care pediatric

referral centers: All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS),

Maulana Azad Medical College (MAMC), and Lady Hardinge Medical College

(LHMC), New Delhi; and Child Development Centre (CDC) in

Thiruvananthapuram.

Consecutive children (2-9 yr) with written informed

consent from their primary caregivers were enrolled into the study from

the Child development and Child neurology outpatient clinics. The

children were recruited until the a priori sample size was

reached. The validation exercise was conducted from June 2008 to April

2010.

|

|

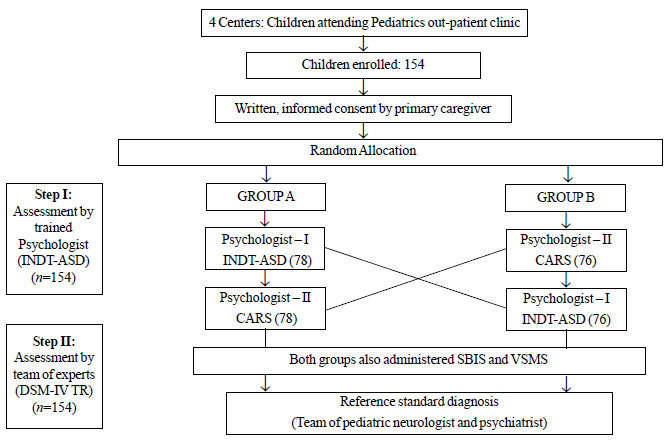

Fig. 1 Process of subject grouping,

randomization and assessment for psychometric validation of

INDT-ASD.

|

Fig. 1 depicts the method for patient

selection, assessment and interview. At every center, the study

coordinator, who was not part of any assessment, evaluated the children

attending the clinic for eligibility and enrolled them in the study. The

subjects were randomly allocated into Group A (N=78) and Group B

(N=76). In Group A, INDT-ASD was administered followed by CARS

and the sequence was reversed in Group B. This was done by independent

psychologists to minimize rating bias. Thereafter, each child was

assessed by a two-member expert team (pediatric neurologist and child

psychiatrist) who based their diagnosis on DSM-IV TR criteria. The

diagnostic protocol required approximately four hours over two days, and

consisted of (i) a face-to-face interview with parent/primary

caregiver, as well as (ii) direct observations of children in

play activities. Each evaluator was blinded to original diagnosis and

assessment results of other evaluator; their evaluations were separately

sealed in opaque envelops immediately after the assessment.

Sample size and sampling technique: Sample size

for diagnostic accuracy was calculated assuming the sensitivity and

specificity of INDT-ASD to diagnose ASD to be 85%, with a precision of

±10% at 95% confidence level. The sample size was calculated to be 50

children in each of the three categories: ASD, other NDD, and normal

development. This sample was also adequate for exploratory factor

analysis during validation [15]. CARS was used to study the convergent

validity of INDT-ASD as well as divide the participants in to mild and

severe autism groups [16]. The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (SK

Kulshreshtha, Hindi version) (SBIS) [17] and Vineland Social

Maturity Scale (VSMS) [18] were used in all subjects to measure

divergent validity of INDT-ASD.

The CARS is a 15-item behavior-rating scale designed

to detect and quantify

symptoms of autism. Each item on the CARS is scored on a Likert

scale, from 1 (no symptoms of autism) to 4 (severe

symptoms). The maximum CARS

score is 60, and a score of 30.5 is suggestive of autism. Children with

scores of 30.5 to 37 are rated as mildly-moderately autistic,and 37.5 to 60 as severely autistic by CARS.

A comprehensive and structured three day training

workshop was conducted for psychologists using standardized manual

developed for INDT-ASD, CARS, SBIS, and VSMS. Separate training groups

(A and B; Fig. 1) of psychologists for INDT-ASD and CARS

were created. Both groups were trained to administer SBIS and VSMS. Two

pediatric neurologists and two child psychiatrists with over ten years

of professional experience were the trainers.

Data processing and statistical analysis:

Participants’ assessment details were entered into a pre-designed

instrument with unique identification numbers. Statistical analysis was

done using SPSS (version 19) and MedCalc (version 12.2.1.0) after data

was entered into Intelligent Character Recognition (ICR) sheets. These

were processed using ABBYY Form Reader 4.0 software. Psychometric

parameters of diagnostic accuracy, construct validity, criterion

validity and internal consistency of INDT-ASD were estimated. The

performance of INDT-ASD was compared with CARS for convergent validity.

IndiaCLEN Review Board and the local Institutional

Review Boards/Ethical Committees of all the participating centers

provided approval for the study. Written informed consent was obtained

from parent/primary caregiver and verbal assent from children, whenever

possible. At the end of the assessment, parents were informed regarding

the child’s needs and appropriate referrals were facilitated, when

warranted.

Results

The mean (SD) age of enrolled children was 64.2

(25.3) months (n=154; 110 boys). Ninety children had average and

64 had subnormal intelligence.

According to the expert diagnosis based on DSM-IV TR

(considered as the gold standard), 51 children were diagnosed as ASD:

autism (44), Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified

(PDD-NOS) (5), Rett syndrome (1), and CDD (1). Severe ASD was

present in 41 and mild-to-moderate in 10 children. Forty-nine "Other

NDDs" included intellectual disability (29), neuro-motor impairments

including cerebral palsy (6), epilepsy (4),

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (2), vision/hearing impairment

(2), and speech and language disorder (1); multiple NDDs were noted

among 5 children.

The INDT-ASD had high diagnostic accuracy against

expert evaluation using DSM-IV-TR for diagnosing ASD (Table I).

The area under-curve (AUC) for INDT-ASD against the expert diagnosis,

was 0.97 (95% CI 0.93, 0.99; P=0.0001). None of the

symptoms/items in the criteria were assigned a score of ‘0’ by more than

half of the children with autism in this study.

The high concordance rate of 82.5% and a significant kappa value

(Cohen’s k=0.89;

95%CI 0.82, 0.97; P=0.001) between the INDT-ASD and expert

diagnosis indicated a high criterion validity for INDT-ASD. The

INDT-ASD had a false positive rate of 5.8%. All the five false positive

cases had "other NDDs": cerebral palsy (N=3), intellectual disability

(N=1), and speech and language disorder (N=1). One child with ASD was

missed (false negative). No normal child was misclassified as having

autism.

TABLE I Diagnostic Accuracy of INDT-ASD Against Expert Diagnosis Using DSM-IV TR Criteria

|

Comparison Group |

Sensitivity

|

Specificity

|

Positive predictive |

Negative predictive |

Positive likelihood |

Negative likelihood

|

|

% (95% CI) |

% (95% CI) |

value % (95%CI) |

value % (95% CI) |

ratio % (95% CI) |

ratio % (95% CI) |

|

ASD vs. normal

|

98.0 (89.5-99.9) |

95.1 (89.0-97.9) |

90.9 (80.4-96.1) |

99.0 (94.5-99.8) |

20.1 (8.5-47.5) |

0.02 (0.003-0.1) |

|

Autism vs. normal

|

95.5 (84.9-98.7) |

90.9 (84.1-95.0) |

80.8 (68.1-89.2) |

98.0 (93.1-99.7) |

10.49 (5.7-19.0) |

0.05 (0.01-0.1) |

|

ASD vs. other NDD

|

98.0 (89.5-99.5) |

87.8 (75.8-94.3) |

89.3 (78.5-95.0) |

97.0 (88.2-99.6) |

8.00 (3.7-16.9) |

0.02 (0.003-0.1) |

|

Autism vs. other NDD

|

95.5 (84.9-98.7) |

82.1 (70.2-90.0) |

80.8 (68.1-89.2) |

95.8 (86.0-98.8) |

5.34 (3.0-9.4) |

0.05 (0.01-0.2) |

|

INDT-ASD total score

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

> 5 and possibility of ASD

|

98.1 (93.0-100) |

90.8 (83.3-95.7) |

85.7 (74.5-93.3) |

98.9 (94.0-100) |

10.6 (9.9-11.5) |

0.02 (0.03- 0.2) |

|

n=51 for ASD, 54 for normal, 44 for autism, 49 for other

NDD; INDT-ASD: INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Autism Spectrum

Disorder; DSM-IV TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders Text Revision; ASD: Autism Spectrum Disorder; NDD:

Neuro-developmental Disorder. |

The convergent validity between the INDT-ASD and CARS

was high (r = 0.73, P= 0.001). Divergent validity

calculated by correlating INDT-ASD scores to the SBIS showed a moderate

negative correlation (r = -0.37; P=0.004).

To investigate the construct validity, we explored

the factor structure of the items in the INDT-ASD. We extracted the

factors with an Eigen value of >1 and thus, a 4-factor structure was

derived. There was no INDT-ASD item that did not achieve the required

factor loading (0.4) on to at least one factor (Web Table I).

In INDT-ASD, 14 symptoms/items loaded onto the

socialization-communication factor, three symptoms/items loaded onto the

repetitiveness-socialization factor, two symptoms/items loaded on to the

restricted repertoire of interest factor, and finally all the 10 sensory

symptom factor also cross-loaded on to other factors. This four-factor

structure explained 85.3% of the variance.

The Cronbach’s a

coefficient for the whole construct of ASD was high (a

= 0.96) suggesting that the INDT-ASD in this

population has high internal consistency and Cronbach’s

a coefficients for

the sub-constructs ranged between 0.82 and 0.96.

The performance of INDT-ASD was equally good among

pre-school (<6 yrs) and primary-school children ( ³6

yrs), among both genders, children with normal and subnormal

intellectual ability, and in children with mild to moderate and severe

ASD (AUC between 0.78 and 0.99).

Discussion

Diagnosis of ASD involves eliciting extensive

history, and detailed observation by experienced clinicians and

psychologists. The sensitivity and specificity of ASD of INDT-ASD was

98% and 95.1%, respectively in our study. This is better than the

performance documented in the DSM-III field trial [19] and the ICD-10

field trial [20]. The DSM-IV TR [21] sensitivity of 93% is closer to our

findings, although the specificity was only 78%. The specificity of

INDT-ASD is similar to that of DSM-5 (95%) but the sensitivity is much

higher (76%) [22].

High Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal

consistency demonstrated that the symptom clusters of INDT-ASD as used

in the Indian context were homogeneous. Some previous studies for

homogeneity of the symptom groups support our findings [21], whereas

others differ with the present findings [23,24].

The agreement rate between INDT-ASD and DSM-IV-TR

(used by expert team) is better than that reported for the DSM-III,

DSM-III-R and ICD-10 [19]. Our false positive rate of 5.8% is comparable

with that of the values reported for DSM-III but lower than that of

DSM-III-R [19]. In our study, children with cerebral palsy and

intellectual disability had impairment in proto-declarative and

proto-imperative pointing and were poorly communicative. This possibly

resulted in false positivity of INDT-ASD. The false negative diagnosis

was also far lower than that reported for DSM-III and DSM-III-R [19].

The only false negative case in the current study had low-average

Intelligence quotient (IQ) with mild autism symptoms.

The convergence between the INDT-ASD and CARS was

high suggesting that the construct of autism as measured by INDT-ASD and

CARS are theoretically related to each other. The negative correlation

between INDT-ASD and IQ as measured by SBIS shows that INDT-ASD has the

ability to diverge from theoretical constructs that are different from

its own, like construct of autism from other childhood disabilities.

However, data for comparison of the concurrent validity for DSM and ICD

are not readily available in the literature.

The factor analysis of the symptom clusters of

autism, as a measure of external validity of the construct has yielded

diverse structure models across different studies [23-28]. For instance,

the study by Tadevosyan-Leyfer, et al. [26] demonstrated a

6-factor structure, while other studies have documented a classical

3-factor [26] like represented in DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 or alternative

3-factor structure [29,30] and even a 1-factor structure explaining the

construct of autism. Our item loading, the 4-factor structure and 85.3%

of variance being explained, makes it closer to the existing model

offered by Tanguay, et al. [25].

The main methodological differences, such as population

characteristics, factor-extraction and factor-retention procedures,

language versions, and statistical approaches, are aspects that might

explain the variability of findings across these factor analyses of the

autism criteria.

As the study was conducted in tertiary-care

hospitals, the participants may not be representative of the children

with autism in the general population and those presenting in primary

and secondary care. Further community-based studies to establish the

sensitivity and specificity of

INDT-ASD are suggested. Another limitation is that the

tool was validated in children 2-9 years of age, and may not capture the

diagnosis in children less than two years of age. Moreover, a larger

sample size could have generated more stable factor structure models

thereby improving the confidence in the validity of identified

constructs, providing more accurate estimates of sensitivity,

specificity, and predictive values.

Establishing the appropriateness of the international

criteria in the Indian context enhances the possibility of accurate

clinical diagnosis and paves way to developing as well as validating new

measures for autism in India. With similar approach and appropriate

modification, tools may be developed for use in other resource limited

settings.

Contributors: All authors have contributed,

designed and approved the study. NKA will act as a guarantor for this

work.

Funding: Ministry of Social Justice

and Empowerment (National Trust), National Institute of Health

(NIH-USA); Fogarty International Center (FIH), and Autism Speaks (USA).

Competing interests: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a

clinical diagnosis by experienced and trained developmental

pediatricians, child psychiatrists and psychologists. Currently

available diagnostic tools are developed for Western populations

and are subject to payment of fee.

What This Study Adds?

• The INDT-ASD is a simple, validated

diagnostic algorithm for Autism Spectrum Disorders in children,

designed on DSM-IV TR criteria through expert consensus.

|

References

1. Volkmar F, State M, Klin A. Autism and autism

spectrum disorders: diagnostic issues for the coming decade. J Psychol

Psychiatry. 2009; 50:108-15.

2. The International Classification of Disease

(ICD-10): Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. Clinical

Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines: World Health Organization,

Geneva; 2002.

3. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed, text rev.)

(DSM-IV-TR): Washington, DC; 2000.

4. Mandy WP, Charman T, Skuse DH. Testing the

construct validity of proposed criteria for DSM-5 autism spectrum

disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012; 51:41-50.

5. Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, Speer L, Embacher

R, Law P, Constantino J, et al. Validation of proposed DSM-5

criteria for autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 2012; 51:28-40.

6. Bakare MO, Munir KM. Excess of non-verbal cases of

autism spectrum disorders presenting to orthodox clinical practice in

Africa - a trend possibly resulting from late diagnosis and

intervention. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2011; 17:118-20.

7. Sell NK, Giarelli E, Blum N, Hanlon AL, Levy SE. A

comparison of autism spectrum disorder DSM-IV criteria and associated

features among African American and white children in Philadelphia

County. Disabil Health J. 2012; 5:9-17.

8. Lord C, Petkova E, Hus V, Gan W, Lu F, Martin DM,

et al. A multisite study of the clinical diagnosis of different

autism spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012; 69:306-13.

9. de Bosset V, Froehlich F, Rey JP, Thorens J,

Schneider C, Wietlisbach V, et al. Do explicit appropriateness

criteria enhance the diagnostic yield of colonoscopy? Endoscopy. 2002;

34:360-8.

10. Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH Jr,

Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. The autism diagnostic

observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and

communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism

Dev Disord. 2000; 30:205-23.

11. Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic

Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for

caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental

disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1994;24:659-85.

12. Fischer RG. The Delphi method: a description,

review and criticism. J Acad Librarianship. 1978:64-70.

13. Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR.

Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical

trials. Health Technol Assess. 1998; 2:1-74.

14. Schopler E, Reichler RJ, DeVellis RF, Daly K.

Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism

Rating Scale (CARS). J Autism Dev Disord. 1980; 10:91-103.

15. McColl E, Jacoby A, Thomas L, Soutter J, Bamford

C, Steen N, et al. Design and use of questionnaires: a review of

best practice applicable to surveys of health service staff and

patients. Health Technol Assess. 2001; 5:1-256.

16. Russell AJ, Mataix-Cols D, Anson MAW, Murphy DGM.

Psychological treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder in people with

autism spectrum disorders – A pilot study. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;

78:59-61.

17. Kulsrestha SK. Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale

and Manual. Hindi Adaptation (Under third revision) Allahabad: Manas

Seva Sansthan Prakashan; 1971.

18. Doll EA. A generic scale of social maturity. Am J

Orthopsychiatry. 1935; 5:180-8.

19. Volkmar FR, Cicchetti DV, Dykens E, Sparrow SS,

Leckman JF, Cohen DF. An evaluation of the Autism Behavior Checklist. J

Autism Dev Disord. 1988; 18:81-97.

20. Spitzer RL, Siegel B. The DSM-III-R field trial

of pervasive developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry.

1990; 29:855-62.

21. Volkmar FR, Klin A, Siegal B, Szatmari P, Lord C,

Campbell M, et al. Field trial for autistic disorder in DSM-IV.

Am J Psychiatry. 1994; 151:1361-7.

22. McPartland JC, Reichow B, Volkmar FR. Sensitivity

and specificity of proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism

spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012; 51:368-83.

23. Ronald A, Happe F, Bolton P, Butcher LM, Price

TS, Wheelwright S, et al. Genetic heterogeneity between the three

components of the autism spectrum: A twin study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 2006; 45:691–9.

24. Ronald A, Happe F, Price TS, Baron-Cohen S,

Plomin R. Phenotypic and genetic overlap between autistic traits at the

extremes of the general population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2006; 45:1206–14.

25. Tanguay PE, Robertson J, Derrick A. A dimensional

classiûcation of autism spectrum disorder by social communication

domains. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998; 37:271-7.

26. Tadevosyan-Leyfer O, Dowd M, Mankoski R, Winklosky

B, Putnam S, McGrath L, et al. A principal component analysis of

the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 2003; 42:864-72.

27. Charman T, Taylor E, Drew A, Cockerill H, Brown

JA, Baird G. Outcome at 7 years of children diagnosed with autism at age

2: predictive validity of assessments conducted at 2 and 3 years of age

and pattern of symptom change over time. Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;

46:500-13.

28. Sigman M, McGovern CW. Improvement in cognitive

and language skills from preschool to adolescence in autism.

J Autism Dev Disord. 2005; 35:15-23.

29. Van Lang NDJ, Boomsma A, Sytema S, de Bildt AA,

Kraijer DW, Ketelaars C, et al. Structural equation analysis of a

hypothesized symptom model in the autism spectrum. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. 2006; 47:37-44.

30. Boomsma A, Van Lang NDJ, De Jonge MV, De Bildt

AA, Van Engeland H, Minderaa RB. A new symptom model for autism

cross-validated in an independent sample. J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2008; 49:809-16.

|

|

|

|

|