From the Department of Cardiology, P.D. Hinduja

Hospital and Medical Research Centre and *Glenmark Cardiac Centre,

Mumbai 400 016, India.

Correspondence to: Dr. Yashkhandwala, P.D. Hinduja

Hospital and Medical Research Center, Veer Savarkar Marg, Mahim,

Mumbai 400 016, India.

E-mail:

[email protected]

Manuscript received: February 1, 2002; Initial

review completed: February 25, 2002; Revision accepted: January 1,

2003.

A two-month-old child having WPW syndrome and

orthodromic tachycardia was on treatment with digoxin, flecainide and

amiodarone. Despite this, he continued to have severe, very frequent

episodes of tachycardia. The left-sided accessory pathway was hence

ablated via a patent foramen ovale.

Key words: Arrhythmia storm, pre-excitation, WPW syndrome.

Radiofrequency ablation (RF) is the standard

treatment for symptomatic WPW syndrome. Usually this procedure is not

performed in very small children due to technical limitations. The case

reported herein was undertaken as a last resort.

Case Report

A one-month-old child born as a full term normal baby

was referred to us with a diagnosis of WPW syndrome. The child first had

an episode of paroxysmal tachycardia at the age of 15 days. Since then

the child had experienced 2 more episodes. During the episodes, the

child would appear limp. The ECG revealed narrow QRS tachycardia at 250

beats/min. The ECG in sinus rhythm suggested a left sided accessory

pathway. The tachycardia could be terminated by intra-venous adenosine.

The child had been started on digoxin and amiodarone. These medica-tions

were continued and a weekly follow-up was advised. The echocardiographic

exam-ination was normal; a patent foramen ovale was seen. Since the

child continued to have episodes of tachycardia, flecainide 1 mg/kg

twice a day was added. Despite this, episodes of tachycardia continued.

At the age of 2 months the child, weighing 3.2 kg was admitted in the

intensive pediatric care unit with tachycardia storm. In a period of 24

hours he had six episodes of orthodromic tachycardia, every time

requiring 1.5 mg/kg adenosine. In view of his precarious state, a

"rescue" ablation was considered.

The procedure was performed under general anesthesia.

Both femoral veins were accessed percutaneously. A 4-F quadripolar

electrode catheter (Bard) was introduced via the left femoral vein into

right ventricle. A 5F (Medtronic) ablation catheter with a 4 mm tip was

introduced via the right femoral vein into the right atrium. Orthodromic

tachycardia was easily inducible and could be terminated by ventricular

extra stimuli. The ablation catheter was passed into the left atrium

through the patent foramen ovale. An early activation site was found in

the left lateral region (Fig. 1). Transient "bumping" of the

pathway was noted by catheter contact. Radiofrequency energy at this

site led to immediate abolition of pre-excitation (Fig. 2). The

peak temperature setting was kept at 60ºC and the maximum temperature

achieved was 53ºC. The ECG next day showed that the preexcitation had

returned. In view of this, flecainide was continued while amiodarone was

stopped. Over the next 5 months the child has not had a single episode

of tachycardia. Digoxin was stopped at 7 months of age. Serial ECGs have

revealed intermittent pre-excitation. He is growing well with normal

milestones. His echocardiogram revealed mild mitral regurgitation but no

structural abnormality of the mitral valve apparatus was seen. At the

last follow up the weight was 9 kg at 11 months of age.

|

|

|

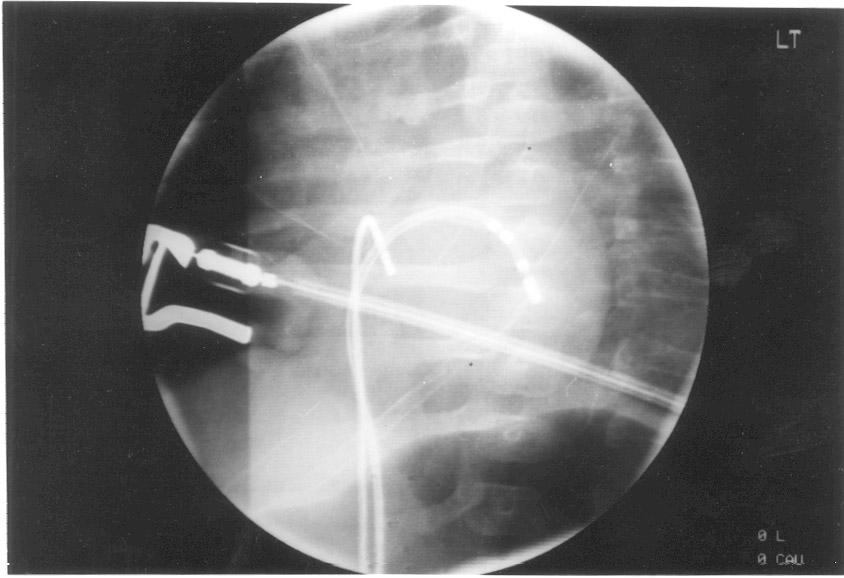

Fig. 1. Fluoroscopy of successful RF

ablation site. (a) 20º RAO, 10º cranial angulation. The ablation

catheter is on mitral annulus across the patent foramen ovale. The

diagnostic catheter is in the right ventricle. (b) 40º LAO view.

The ablation catheter tip is seen in the left lateral region. |

|

|

Fig. 2. RF energy delivery. Preexcitation is

abolished from 10th QRS complex onwards. The initial 9 QRS

complexes show a negative delta wave in lead aVF and a positive

delta wave in lead V1, which disappear later. |

Discussion

RF ablation is rarely performed in infancy. The small

diameter of femoral vessels imposes severe limitations on catheter

choices. Apart from vascular complications, there are concerns of damage

to the fragile intracardiac structures at such a tender age. We

undertook RF ablation after all other measures had failed. The return of

pre-excitation in our patient was unusual, because adenosine had

demonstrated transient AV block after RF ablation. The intermittent

nature of pre-excitation at follow-up is indicative of a long antegrade

refractory period of the accessory pathway. The absence of tachycardia

recurrence suggests that retrograde conduction over the pathway has been

markedly diminished, if not eliminated by the RF ablation.

There are apprehensions regarding increase in RF

lesion size with growth based on studies in lambs(1). Hence RF ablation

in infancy is undertaken only when severe tachycardia persists despite

adequate trial of drug therapy. There are several reported series of RF

ablation in children(2,3,4), but the proportion of infants in these

studies have been very small. Our patient is the youngest reported

hitherto from India. A previous report from India(5) highlighted a

similar problem in a thirteen month old child. The mild mitral

regurgitation noted in our patient has been well tolerated. It is

possible that the RF lesion in some way has led to this regurgitation.

However the absence of any visible damage to the leaflets or chordae is

reassuring. The satisfactory clinical progress that we observed indicate

a good prognosis in this regard.

Contributors: BD conducted initial clinical and

echocardiographic evaluation, CKP assisted in the RF ablation procedure,

KC assisted in the management and help in writing the manuscript, YL

helped in patient care and preparation of the manuscript and will act as

guarantor of the paper.

Funding: None.

Competing Interests: None stated.