Munni Ray

Pratibha Singhi

Prabhjyot Malhi

Anil Bhalla

From the Division of Pediatric Neurology,

Department of Pediatrics, Advanced Peditric Center, Post

Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh

160 012, India.

Reprint requests: Dr. Pratibha D. Singhi,

Additional Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Post Graduate

Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160 012,

India.

Manuscript Received: April 13, 1999;

Initial review completed: May 18, 1999;

Revision Accepted: August 30, 1999

Velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS) is a genetic

disorder with an estimated frequency of 1 in 4000 live births(1).

This disorder is characterized by cardiac defects, cleft palate,

learning disabilities and mild facial dysmor-phology(2). The

identification of these patients is difficult because it is a

multisystem syndrome with numerous anomalies, many of which are

considered minor and found in general population(3). The enormous

variability of this condition is seen by the different clinical

features which are present in the affected members of the same

family(4,5). There is a paucity of documentation on this subject

in Indian literature. Hence we report a pair of siblings born to

nonconsanguineous parents who had variable clinical phenotype.

Case Reports

Case 1:

A 7½-year-old boy was referred for

evaluation of developmental delay and abnor-mal behavior. He was

delivered normally at term with an uneventful perinatal period. He

had cleft palate which was repaired at 4 years of age. He had

delay in acquiring milestones in all sectors. The parents reported

poor scholastic performance as well as hypernasality of speech

since he started verbalizing. He had frequent chest infections and

was diagnosed to have a ventricular septal defect at 1 year of

age.

On physical examination the patient was short

statured, [height - 115.6 cm (93% of median)] and had microcephaly

[head circumference 44.3 cm (<3 SD)]. He had a long face with

prominent nasal bridge and a broad tip of the nose. He had flat

maxillae, microg-nathia and retruded mandible with a repaired

cleft palate. The child had an everted upper lip with short

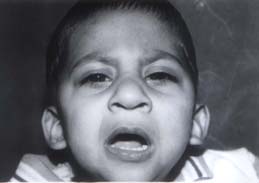

philtrum. The ears were prominent and symmetric (Fig. 1).

He had typical slender hands with tapering fingers which were

hyperextensible (Fig. 2).

On evaluation of intelligence, his IQ was 32.

Social quotient assessment by VSMS scale was 38.6. On

developmental profile, his academic age was 2 years 4 months and

his social age was 3 years 6 months. His behavior pattern was

preservative, stereotypic, and not goal directed.

Chest X-ray revealed cardiomegaly and

echocardiography showed a small perimem-branous ventricular septal

defect. His bone age was normal; computed tomography scan of brain

and ultrasound abdomen for kidneys did not reveal any structural

defects. Ophthalmo-logical assessment and audiometry was normal.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Typical facial findings in Case 1

with velocardiofacial syndrome.

|

Fig. 2. Hands of Case 1 showing spindle

shaped and tapering fingers. |

Case 2:

This 1½-year-old male was the

younger brother of Case 1. He was delivered full term of an

uneventful pregnancy and had no birth asphyxia. The child had

feeding difficulties and failure to thrive since birth. There was

history of nasal regurgitation of milk and he also had a cleft

palate which was repaired at 1 year of age. He had developmental

delay in all sectors. The parents complained that the child was

floppy since birth and also had constipation.

On examination he had dysmorphic features. His

length was 72 cm (90% of median) and head circumference was 42.5

cm (<3 SD). He had narrow palpebral fissures, maxillary

deficiency, microsomia, small chin and a large fleshy nose, a

broad nasal bridge with asymmetric prominent auricles (Figs. 3

& 4). Cardiovascular examination was normal. Neurological

assessment revealed gross motor and fine motor and language delay.

The child was hypotonic but reflexes were normally elicitable.

On investigation the echocardiography, CT scan

head, bone age, thyroid profile, serum calcium and ultrasound

abdomen were within normal limits.

Both the children were diagnosed as cases of

velocardiofacial syndrome and they were provided rehabilitation

particularly speech therapy and special education. The parents

were examined in details and were not found to have any features

of the syndrome. The grandparents could not be contacted.

The parents were informed about the variable

penetrance and manifestations of the syndrome and its associated

problems. They were advised to get chromosomal anlaysis including

FISH analysis and to bring the children for periodic follow up.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Facial features of velocardiofacial syndrome in

Case 2.

|

Fig. 4. Lateral view of face of Case 2. |

Discussion

VCFS was initially described by Sphrintzen et

al. in 1978 as a multiple malformation syndrome that included

clefting of palate, cardiac anomalies, a characteristic facial

phenotype and learning disability(6). Since then more than 40

physical anomalies including hypocalcemia, hypotonia, mental

retardation, thrombocytopenia, blood vessel anomalies such as

tortuous retinal vessels have been described(7). A newly

recognized finding is the presence of psychiatric disorder in

these patients(8).

The typical patient with VCFS presents with a

cluster of velar, cardiac, facial, digital and mental findings.

All these features were amply demonstrated in Case 1. The

characteristic facial features found in these cases are a long

vertical face, large fleshy nose, narrow alar base, flattened

malar region, narrow palpebral fissures, retrognathia, small

downturned mouth and prominent ears(6). Both the children had

characteristic facies and were also short statured as is found in

30% of cases(2). A small head circumference which was present in

both the cases is a common finding. Recently, structural brain

defects have been described(9) but they were not present in either

of the cases.

The oral manifestations consist of clefts of

the secondary palate and velopharyngeal insufficiency(10). Both

the brothers had cleft palate which were repaired. The elder sib

had hypernasality of speech, which was probably due to

velopharyngeal insufficiency. The history of feeding difficulties,

failure to thrive and nasal regurgitation of milk in the younger

boy could also be explained by the presence of the oral

manifestations.

These children commonly have motor

incoordination and poor development of numerical concepts. These

along with poor abstract reasoning leads to increasingly poor

psychological, language and academic performance(9). Personality

may tend towards preservative stereotypic behavior as was seen in

Case 1.

The problems with which such children generally

present in infancy were all seen in Case 2, i.e., hypotonia,

development delay, constipation and failure to thrive.

Not all principal features are present in each

case; particularly cardiac disease is not an essential feature.

The elder sib had VSD but the younger sib did not. The younger sib

also did not have typical digital findings like spindle shaped

slender fingers. Frequent upper respira-tory tract infections,

pneumonia or bronchitis are common in VCFS as were reported only

in the elder sib(9). Studies on monozygotic twins and affected

members of the same family who have different clinical features

show the enor-mous variability seen in this conditions(4,5).

In 1993 the New Castle and Tyne group suggested

the acronym CATCH22 as an alternative name for this syndrome [C =

cardiac anomalies, A = abnormal facies, T = thymic hypoplasia, C =

cleft palate, H = hypocalcemia, 22 = affected chromosome](11).

Both hypocalcemia and thymic hypoplasia were absent in both the

cases. Hypothyroidism which has also been described as an

associated finding was absent in these sibs(7). Conductive hearing

loss caused by chronic otitis media found in 77% of the typical

cases was not found in either of the sibs(12).

The identification of this disorder is dificult

because it is a multisystem syndrome with numerous anomalies.

There is no clinical find-ing which is pathognomonic for diagnosis

of VCFS nor is there a composite of major and minor criteria that

can be used to make a definitive diagnosis(3). Therefore it is

important to consider the diagnosis in any patient with more than

one of the clinical findings characteristic of this syndrome.

As more is learned and new clinical findings

are uncovered in patients with VCFS, the spectrum of affected

patients encompasses many patients previously described as having

DiGeorge syndrome (DGS), Pierre Robin Sequences (PRS) and the

CHARGE associa-tion. Both our cased did not have hypocalcemia,

thymic aplasia, short philtrum of lip and anti-mongoloid slant of

eyes which are characteristic of DGS. The pair of brothers did not

have glossoptosis which is one of the three features like cleft

palate and micrognathia which are found in PRS. On the contrary

many other facial features, cardiac findings and skeletal changes

characteristic of VCFS were found in them. These children did not

fit into CHARGE association as there was absence of coloboma in

the eyes, choanal atresia, genital hypoplasia and deafness.

Most cases of VCFS are sporadic, but when

inherited, it has an autosomal dominant pattern of transmission

with variable penetrance. It results from a deletion of 22 q

11.2(13). High resolution Karyotyping and DNA analysis which is

required to pick up the genetic make up of these cases is

advisable.

1. Burn J, Goodship J. Congenital heart

disease. In: Emery and Rimoin’s principles and Practice

of Medical Genetics, 3rd edn. Eds. Rimoin DL, Connor JM, Pyeritz

RE. New York, Churchill Livingstone, pp 767-828.

2. Smith DW. Shprintzen syndrome (Velocardio-facial

syndrome) In: Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformations,

5th edn. Ed. Smith DW. Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Co; 1997; pp

266-267.

3. Motzkin B, Marlon R, Goldberg R, Shprintzen

R, Saenger P. Variable phenotypes in velocardio-facial syndrome

with chromosomal deletion. J Pediatr 1993; 123: 406-410.

4. Goodship J, Cross I, Scambler P, Burn J.

Monozygotic twins with chromosome 22q 11 deletion and discordant

phenotype. J Med Genet 1995; 32: 746-748.

5. Holder S, Winter R, Kamath S, Scambler P.

Velocardiofacial syndrome in a mother and daughter: Variability of

the clinical phenotype. J Med Genet 1993; 30: 825-827.

6. Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg RB, Lewin ML, Sidoti

EJ, Berkman MD, Argamaso RV, et al. A new syndrome

involving cleft palate, cardiac anomalies, typical facies and

learning disabilities: Velocardiofacial syndrome. Cleft Palate J

1978; 5: 56-62.

7. Goldberg R, Motzkin B, Marion R, Scambler PJ,

Shprintzen RJ. Velocardiofacial syndrome: A review of 120

patients. Am J Med Genet 1993; 45: 313-319.

8. Carlson C, Papolos D, Pandita RK, Faedda GL,

Veit S, Goldberg R, et al. Molecular analysis of velocardio-facial

syndrome patients with psychiatric disorders. Am J Hum Genet 1997;

60: 851-859.

9. Pike AC, Super M. Velocardiofacial syndrome.

Postgrad Med J 1997; 73: 771-775.

10. Finkelstein Y, Zohar Y, Nachmani A, Talmi

YP, Lerner MA, Hauben DJ, et al. The otolaryngologist and

the patient with velocardio-facial syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg 1993; 119: 563-569.

11. Wilson D, Burn J, Scambler P, Goodship J.

Digeorge syndrome part of Catch 22. J Med Genet 1993; 30: 852-856.

12. Shprintzen RJ, Goldberg RB, Young D,

Wolford I. The velocardiofacial syndrome: A clinical and genetic

analysis. Pediatrics 1981; 67: 167-172.

13. Carlson C, Sirotkin H, Pandita R, Goldberg R, McKie J,

Wadey R, et al. Molecular definition of 22q 11 deletions in

151 Velocardiofacial syndrome patients. Am J Hum Genet 1997; 61:

620-629.

|