|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57: 222-227 |

|

Comparison of Phenytoin, Valproate and

Levetiracetam in Pediatric Convulsive Status Epilepticus: A

Randomized Double-blind Controlled Clinical Trial

|

Vinayagamoorthy Vignesh, Ramachandran Rameshkumar

and Subramanian Mahadevan

From Division

of Pediatric Critical Care, Department of Pediatrics,

Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and

Research, Puducherry, India.

Correspondence to: Dr

Rameshkumar Ramachandran, Associate Professor, Division of

Pediatric Critical Care, Department of Pediatrics,

Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and

Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: June

26, 2019;

Initial review: November 04, 2019;

Accepted: January 20, 2020.

Trial Registration: CTRI/2016/05/006908.

|

|

Objective: To compare

the efficacy of phenytoin, valproate, and levetiracetam in

the management of pediatric convulsive status epilepticus.

Design: Randomized double-blind

controlled clinical trial.

Setting:

Pediatric critical care division in a tertiary care

institute from June, 2016 to December, 2018.

Participants: 110 children aged three month

to 12 year with convulsive status epilepticus.

Intervention: Patients not responding to

0.1 mg/kg intravenous lorazepam were randomly assigned

(1:1:1) to receive 20 mg/kg of phenytoin (n=35) or valproate

(n=35) or levetiracetam (n=32) over 20 minutes. Patients

with nonconvulsive status epilepticus, recent hemorrhage,

platelet count less than 50,000 or International normalized

ratio (INR) more than 2, head injury or neurosurgery in the

past one-month, liver or kidney disease, suspected or known

neurometabolic or mitochondrial disorders or structural

malformations, and allergy to study drugs; and those who

were already on any one of the study drugs for more than one

month or had received one of the study drugs for current

episode, were excluded.

Outcome measure:

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients that

achieved control of convulsive status epilepticus at the end

of 15 minutes after completion of the study drug infusion.

Secondary outcomes were time to control of seizure, rate of

adverse events, and the requirement of additional drugs to

control seizure, length of ventilation, hospital stay, and

functional status after three months (Glasgow Outcome

Scale).

Results: The study was

stopped after the planned mid-interim analysis for futility.

Intention to treat analysis was done. There was no

difference in primary outcome in phenytoin (31/35, 89%),

valproate (29/35, 83%), and levetiracetam (30/32, 94%)

(P=0.38) groups. There were no differences between the

groups for secondary outcomes. One patient in the phenytoin

group had a fluid-responsive shock, and one patient in the

valproate group died due to encephalopathy and refractory

shock.

Conclusions: Phenytoin,

valproate, and levetiracetam were equally effective in

controlling pediatric convulsive status epilepticus.

Keywords: Anti-epileptic drugs, Management,

Outcome Seizure.

|

|

Convulsive status epilepticus (CSE) is the most

common time-bound pediatric neurological emergency worldwide, where

delayed control is associated with neurological sequelae and risk of

mortality [1]. Half of the children in an Indian emergency department

had convulsive status epilepticus at their first presentation without

having any history of prior seizure [2]. The available evidence supports

that benzodiazepines should be the drugs of first choice for CSE [3].

Subsequently, intravenous phenytoin/fosphenytoin remains the most used

antiepileptic drug. The other reasonable options are valproate,

levetiracetam and phenobarbital. There is insufficient evidence to

support the use of one particular drug over the others [1,4,5]. Thus, we

compared the efficacy of phenytoin, valproate, and levetiracetam in

pediatric convulsive status epilepticus. We hypothesized that

levetiracetam would be associated with better control of seizures as

compared to phenytoin and valproate in pediatric convulsive status

epilepticus.

METHODS

This

randomized, double blinded-controlled clinical trial was

conducted in the Division of pediatric critical care of a

tertiary-care academic institution between June, 2016 to

December, 2018. The institutional ethics committee approved the

study and written informed consent was obtained from

parents/legal guardians. Children aged 3 month to 12 years with

convulsive status epilepticus (clonic, tonic, tonic-clonic, and

myoclonic, focal or generalized) were enrolled. Children with

either of the following conditions were excluded (i)

non-convulsive status epilepticus, (ii) active or recent

hemorrhage (less than one week) from any site, (iii) documented

platelet count less than 50,000, or international normalized

ratio more than two, (iv) head injury or neurosurgery in the

past one month, (v) acute or chronic liver or kidney disease,

(vi) suspected or known neurometabolic or mitochondrial

disorders or structural malformations, (vii) known or suspected

allergy to any of the study drugs, (viii) patient with epilepsy

already on levetiracetam (more than 20 mg per kg per day) or

valproate (more than 20 mg per kg per day) or phenytoin (more

than 5 mg per kg per day) for more than one month, and (ix)

patients who have received the appropriate dose of study drug(s)

for the current episode of convulsive status epilepticus.

Convulsive status epilepticus was defined as continuous seizure

activity or recurrent seizure activity without regaining

consciousness, lasting more than five minutes [6,7]. Status

epilepticus and its etiology were classified as per

International League Against Epilepsy guidelines [6].

A

computer-generated and unstratified block randomization with

variable block sizes of three, six, and nine were used. A person

not involved in the study performed the random number

allocation. Individual assignments were placed in sequentially

numbered opaque sealed envelopes (SNOSE) with a three-component

alphanumerical code. The envelope contained an instruction slip

about the preparation of the study drug. Nursing personnel, who

was not part of the research team, opened the envelope and

prepared the study drug concentration of 5 mg/mL in 0.9% normal

saline dilution in the syringe. Each syringe was labeled with

the same alphanumerical code, and study drug dose (4 mL per kg

over 20 minute). The person who prepared the study drug was

blinded to the patient’s identity. Injection phenytoin sodium

(Ciroton, 2 mL per 100 mg, Ciron Pharmaceuticals, India),

injection sodium valproate (Valprol, 5 mL per 500 mg, Intas

Pharmaceuticals, India) and injection levetiracetam (Levesam, 5

mL per 500 mg, Abbott Ind. Ltd, India) were used in this study.

The Institute’s central pharmacy supplied the study drugs. The

participants, treating doctors and nurses administering the

drugs, as well as the investigators and research personnel, were

unaware of the treatment assignments until control of seizure.

Later, the study drug was unblinded to the treating team to

continue maintenance therapy. The person who collected the data

and entered it into the datasheet, and the study statistician

were unaware of the treatment assignments until final analyses.

At the time of analysis, another person not involved in the

study and SNOSE preparation decoded the treatment assignment by

using the code from the online stored datasheet.

Enrolled patients were managed by stabilizing the airway,

breathing and circulation, and using intravenous lorazepam 0.1

mg/kg in the pediatric emergency room. Patients not responding

to intravenous lorazepam received the study drug at the dose of

20 mg kg over 20 minutes as an intravenous infusion. If

convulsions were not controlled with the study drug or there was

recurrence of seizure after control by study drug, additional

antiepileptic drugs were administered as per the treating team’s

discretion. The patients were shifted to the pediatric intensive

care unit or ward for further management and etiological workup,

as per unit protocol. Survivors were followed for three months

post-discharge. The functional status was assessed using Glasgow

outcome scale score, which ranges from one to five (higher the

score better the neurological function).

The primary

outcome was the proportion of patients who achieved control of

convulsive status epilepticus at the end of 15 minutes after

completion of study drug infusion (i.e., 35 minutes after

starting the study drug infusion). The secondary outcomes were

(i) time (minutes) taken to control seizure from the initiation

of study drug infusion, (ii) proportion of patients who required

additional drug to abort clinical seizures, (iii) rate of

adverse events, (iv) length of mechanical ventilation if

ventilated; (v) hospital stays including pediatric intensive

care stay, (vi) in-hospital mortality, and (vii) functional

status at three months of follow-up by Glasgow Outcome Scale.

Based on a study by Mundlamuri, et al. [8], control of

convulsive status epilepticus by phenytoin and valproate was

found to be at 68%. We, therefore, assumed that levetiracetam

might increase the control rate to 88%. With a two-sided alpha

of 5% and 80% power, 68 patients were needed in each group

(nQuery + nTerim3.0 version software). Interim analysis was

planned at the end of 50% enrollment. The trial progress was

reviewed yearly by the institute’s ethics and data and safety

monitoring committee, including an independent statistician who

was also a physician. The trial had to be stopped prematurely

after the planned interim analysis contended that it was futile

to continue the study further.

Statistical analyses:

Data of all the patients were analyzed according to their

assigned groups (Intention to treat). The normality of data was

checked with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z test. Continuous data were

compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) if normally

distributed or by Kruskal-Wallis test if non-normally

distributed and proportions with Chi-square test. All tests were

two-tailed, and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically

significant. SPSS version 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY)

and Epi Info 7 (7.0.9.7, CDC, Atlanta, GA) were used for data

analysis.

RESULTS

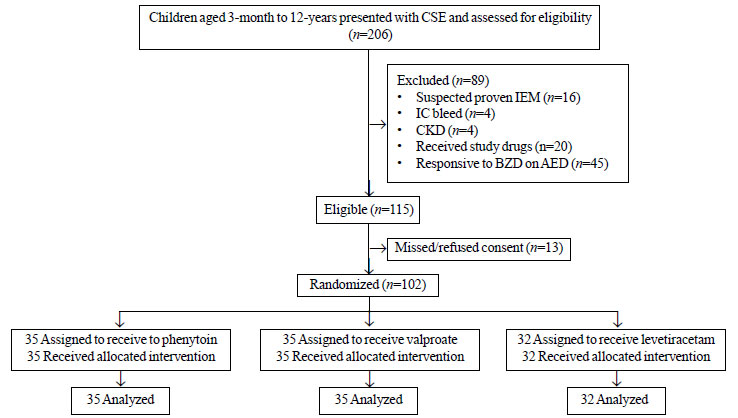

The study

flow is depicted in Fig.1. The baseline

characteristics and investigations were comparable in the study

groups (Table I). The median duration of

seizure, before enrollment, was 10 minutes in each group. Seven

(7%) of patients received normal saline bolus and six (6%)

patients received vasoactive therapy. Five patients in each

group received osmotherapy for cerebral edema. Antibiotics and

antivirals were given in 40 (39.2%) and 16 (16%) patients,

respectively (Table I). Computerized tomography

was done in 55 (54%) patients, and magnetic resonance imaging

was done in 41 (40%) patients. Abnormalities were found in 18

studies, with tubercular involvement in two children and

multiple neurocysti-cercosis in one child. Control of convulsive

status epilepticus was higher in the levetiracetam group (94%)

as compared to the phenytoin group (89%) and valproate group

(83%), though statistically no difference was found (P=0.38).

The mean time to control of seizure was three minutes (P=0.42).

Additional drug to control the seizure after control of seizure

by study drug was higher in the phenytoin group (26%) as

compared to the valproate (14%) and levetiracetam (13%) groups.

Twenty-eight patients (27.5%) were shifted to the pediatric

intensive care unit; mean stay was significantly lower in the

phenytoin group (Table II). One patient died in

the valproate group due to encephalopathy and refractory shock;

this death was not thought to be due to the study drug. No

intervention-related serious adverse event was noted, except for

one patient in the phenytoin group who had a fluid responsive

shock.

|

| Fig. 1 Study flow.

CSE: Convulsive status epilepticus; IEM: Inborn error of

metabolism; IC bleed: Intracranial bleed; CKD: Chronic

kidney disease; BZD: Benzodiazepine; AED: Anti epileptic

medication. |

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of Children With Convulsive Status Epilepticus in the Three Treatment Groups

|

Variable

|

Phenytoin group

(n=35) |

Valproate group

(n=35) |

Levetiracetam

group (n=32) |

P value

| |

*Age (mo) |

44 (43) |

59 (44) |

58 (50) |

0.32 | |

Male |

19 (54.3) |

21 (60) |

18 (56.2) |

0.89 | |

*Body Mass Index, z score |

- 1.7 (2) |

- 1.1 (1.9) |

- 1.6 (2) |

0.32 | |

*(cm) Head circumference |

46.4 (4.2) |

48.3 (3.5) |

47 (4.8) |

0.16 | |

#PRISM-III |

5 (3 - 8) |

4 (2-7) |

3 (0-5) |

0.17 | |

#Duration of seizure, prior to enrollment (min) |

10 (10 - 23) |

10 (10-15) |

10 (10-18) |

0.57 | |

Fever history |

23 (66) |

15 (43) |

15 (47) |

0.13 | |

Classification of status epilepticus, n (%) | | | |

0.44 | |

Generalized convulsive |

26 (74) |

31 (88) |

24 (75) | | |

Focal motor |

5 (14) |

2 (6) |

6 (19) | | |

Focal onset evolving into bilateral convulsive SE |

4 (11) |

2 (6) |

2 (6) | | |

Family history of seizure disorder |

4 (11) |

2 (6) |

1 (3) |

0.38 | |

Developmental delay |

5 (14) |

8 (23) |

5 (16) |

0.60 | |

Hypocalcemia |

4 (11) |

3 (9) |

2 (6) |

0.76 | |

Abnormal CT head (n=55) |

4 / 23 (17) |

3/16 (19) |

1/16 (6) |

0.37 | |

‡MRI Brain* (n=41) |

5 / 12 (42) |

2/13 (15) |

5/16 (31) |

0.43 | |

‡Electroencephalographic abnormality |

15 / 27 (56) |

17 /29 (59) |

12/21 (57) |

0.97 | |

Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis |

10 (29) |

7 (20) |

4 (13) |

0.27 | |

Etiology | | | |

0.28 | |

Acute |

16 (46) |

7 (20) |

14 (44) | | |

Remote |

9 (25) |

7 (20) |

5 (16) | | |

Acute on remote |

1 (3) |

2 (6) |

- | | |

Febrile status epileptics |

2 (6) |

2 (6) |

2 (6) | | |

Unknown (ie, cryptogenic) |

7 (20) |

17 (48) |

11 (34) | | |

All values in no. (%) except *mean (SD) or #median (IQR); Hypocalcemia defined as ionized calcium less than one mmol/L or total serum calcium less than 8.5 mg/dL; PRISM: *Pediatric risk mortality score; CT: Computer tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; ‡done during the follow-up. |

TABLE II Outcome in Children With Convulsive Status Epilepticus in the Three Treatment Groups (N=102)

|

Outcome |

Phenytoin group |

Valproate group |

Levetiracetam |

P value | |

(n=35) |

(n=35) |

group (n=32) | | |

Primary outcome, n (%) |

31 (89) |

29 (83) |

30 (94) |

0.38 | |

Secondary outcomes | | | | | |

Time to control seizure (min), mean (SD) |

3 (1.2) |

3.2 (1.4) |

3.1 (1.3) |

0.42 | |

‡Additional drug to control the seizure, n (%) |

4 (11.4) |

6 (17) |

2 (6) |

0.38 | |

$Additional drug to control seizure, n (%) |

8 / 31 (26) |

4 / 29 (14) |

4 / 30 (13) |

0.35 | |

Mechanical ventilation, n (%) |

7 (20) |

5 (14) |

3 (9) |

0.47 | |

Length of mechanical ventilation (d), mean (SD) |

2 (1.2) |

7 (5.5) |

3 (1.7) |

0.08 | |

PICU shifting, n (%) |

15 (43) |

7 (20) |

6 (19) |

0.04 | |

PICU stay (d), mean(SD) |

4 (2.4) |

10 (4.5) |

6 (3.7) |

0.005 | |

Hospital stay (d), mean (SD) |

6.1 (4.1) |

5.5 (5.4) |

7 (7.4) |

0.55 | |

Functional status (at discharge), n (%) | | | |

0.46 | |

GOS score-1 |

- |

1 (3) |

- | | |

GOS score-3 |

- |

1 (3) |

1 (3) | | |

GOS score-4 |

8 (23) |

12 (34) |

6 (19) | | |

GOS score-5 |

27 (77) |

21 (60) |

25 (78) | | |

#Functional status (at 3 mo), n (%) | | | |

0.06 | |

GOS score-3 |

- |

- |

1 (3) | | |

GOS score-4 |

3 (9) |

10 (29) |

3 (9) | | |

GOS score-5 |

32 (91) |

24 (71) |

28 (88) | | |

Mortality, n (%) |

- |

1 (2.8) |

- |

- | |

Adverse event, n (%) |

1 (2.8)* |

- |

- |

- | |

PICU: Pediatric Intensive Care Unit; GOS: Glasgow Outcome Scale; *fluid responsive shock, #n=34 for valproate group, $after control of seizure by study drug; ‡no response to study drug. |

DISCUSSION

The present randomized controlled study found that phenytoin,

valproate, and levetiracetam are safe and equally efficacious in

the management of pediatric status epilepticus. Our study

findings are consistent with recent controlled studies. A study

in adults [8], compared phenytoin (20 mg per kg), valproate (30

mg per kg) and levetiracetam (40 mg per kg) after 0.1 mg per kg

of lorazepam found that there was no difference in the control

of generalized convulsive status epilepticus (68% vs. 68% vs.

78%) and 6% of levetiracetam group patients had post-ictal

psychosis. A more recent study [9] in both children and adults,

comparing fosphenytoin (20 mg of phenytoin equivalent per kg),

valproate (40 mg per kg) and levetiracetam (60 mg per kg), found

that cessation of status epilepticus and improvement in the

level of consciousness at 60 minutes of starting study drug

infusion was similar in all three groups (45%, 46%, and 47%,

respectively). The ConSEPT study [10] and the EcLiPSE study [1]

compared 20 mg per kg phenytoin and 40 mg per kg levetiracetam.

Clinical cessation of seizure activity in children with status

epilepticus refractory to benzodiazepine was similar in both

studies (60% vs. 50% and 64% vs. 70%, respectively) [1,10].

Isguder, et al. [11] reported that control of status

epilepticus in pediatric patients was 71.8% with valproate and

levetiracetam. The lower rate of seizure control could be due to

a longer median duration of status epilepticus of 75 minutes, as

compared to 10 minutes in our study.

A meta-analysis in

pediatric status epilepticus found that valproate had a higher

efficacy of 75.7% as compared to levetiracetam (68.5%) and

phenytoin (50.2%) after administration of benzodiazepine [12].

Another meta-analysis of five randomized studies, which included

one pediatric study (valproate vs. phenytoin), with insufficient

information about random sequence generation and allocation

concealment, found that there was no difference in clinical

seizure control in both direct (valproate vs. phenytoin; 77% vs.

76% and levetiracetam vs. phenytoin; 72% vs. 68%) and indirect

(levetiracetam vs. valproate; 72% vs. 77%) comparison [13]. Our

study found a relatively higher control rate of seizure; as

compared to other published studies [1,,8-13], possibly due to

shorter duration of seizures before treatment in our study.

We found that the proportion of patients shifted to the

pediatric intensive care unit was significantly higher in the

phenytoin group. This could be due to the underlying illness in

addition to the drug effects on neurological function. Valproate

is reported to have a lower risk of cardiorespiratory compromise

and a lack of sedative effect [14,15].

Our study had

certain methodological differences from other similar studies.

We assessed the absence of seizure 15 minutes after completion

of study drug infusion, i.e. 35 minutes after starting the

infusion, and the mean time taken to control of seizure was

three minutes. We randomized the patients who did not respond to

the benzodiazepine and used intention to treat analysis. This

finding differs from the EcLiPSE study, which found that median

time from randomization to the cessation of convulsive status

epilepticus was similar in phenytoin and levetiracetam group

(45-minute vs. 35-minute) and ConSEPT study assessed the

clinical cessation of seizure activity five minutes after

completion of infusion of the study drug with a different

infusion time used for administration of study drugs (over five

minutes and over 20 minutes) [1,10]. Another controlled study by

Kapur, et al. [9] assessed the absence of seizure and recovery

of consciousness after 60 minutes of starting the study drug

infusion, and emergency unblinding before 60 minutes was

considered a protocol deviation. Hence, the time limit followed

for assessment of primary endpoint in our study is in line with

the International League Against Epilepsy operational time point

(t1 and t2) of status epilepticus [6].

Apart from the

duration of seizure, age and underlying etiologies have a

different impact on the prognosis of neurological outcome, even

if assuming a similar seizure type [6]. In our study, these

prognostic factors were not analyzed. Though it is difficult to

differentiate the role of each of the prognostic factors, data

from larger studies could allow for redefining of the risk of

long-term neuro-morbidity. Another strength of our study was

that the neurological outcome at three-month was assessed. This

is in contrast to six previous open-labeled controlled studies

with valproate and two with levetiracetam, no follow-up details

were provided [5]. Our study did not include the recovery of

postictal consciousness, long term drug-related adverse effects,

and behavioral assessment. Future studies with large sample

size, preferably multicentric, should focus on children with

different etiologies, including liver and hematological

diseases, with stratification of the duration of seizure and

convulsive versus non-convulsive seizures.

In conclusion,

our study shows that phenytoin, valproate, and levetiracetam are

equally effective in controlling seizure in the management of

pediatric convulsive status epilepticus with a similar

neurological outcome at three-month follow-up.

Acknowledgments: S Raja Deepa, JIPMER Campus, Puducherry, India

for review and editing of the manuscript; Mr Rakesh Mohindra,

Punjab University, Chandigarh, India. Mrs Thenmozhi M for

helping with statistical analysis and Mrs. Harpreet Kaur, Punjab

University, Chandigarh, India, Mrs. Neelima Chadha (Tulsi Das

Library, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India) for helping with medical

literature search.

Contributors: VV,RR,SM: Management of

the patients and study supervision. VV: collected the data,

reviewed the literature and drafted the first manuscript: SM:

contributed for protocol development, review of literature and

manuscript. RR: conceptualized the study, reviewed the

literature and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors

approved the final version of the manuscript. RR: is the

guarantor of the paper.

Funding: In part by the

institutional and departmental fund;

Competing interest:

None stated.

|

WHAT THIS STUDY ADD?

•

Phenytoin, valproate, and levetiracetam at a dose of 20

mg/kg infusion over 20 minute were equally efficacious in the

management of pediatric convulsive status epilepticus not

responding to single dose of lorazepam, and patients had similar

neurological outcome at three-month follow-up.

|

REFERENCES

1. Lyttle MD, Rainford

NEA, Gamble C, Messahel S, Humphreys A, Hickey H, et al.

Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of

paediatric convulsive status epilepticus (EcLiPSE): A

multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet.

2019;393:2125-34.

2. Gulati S, Kalra V, Sridhar MR.

Status epilepticus in Indian children in a tertiary care

center. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:105-8.

3. McTague

A, Martland T, Appleton R. Drug management for acute

tonic-clonic convulsions including convulsive status

epilepticus in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2018;1:CD001905.

4. Verrotti A, Ambrosi M, Pavone P,

Striano P. Pediatric status epilepticus: Improved management

with new drug therapies? Expert Opin Pharmacother.

2017;18:789-98.

5. Trinka E, Kälviäinen R. 25 years

of advances in the definition, classification and treatment

of status epilepticus. Seizure. 2017;44:65-73.

6.

Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, Rossetti AO, Scheffer IE,

Shinnar S, et al. A Definition and Classification of Status

Eepilepticus – Report of the ILAE Task Force on

Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia.

2015;56:1515-23.

7. Brigo F, Sartori S. The new

definition and classification of status epilepticus: What

are the implications for children? Epilepsia.

2016;57:1942-3.

8. Mundlamuri RC, Sinha S,

Subbakrishna DK, Prathyusha PV, Nagappa M, Bindu PS, et al.

Management of generalised convulsive status epilepticus

(SE): A prospective randomised controlled study of combined

treatment with intravenous lorazepam with either phenytoin,

sodium valproate or levetiracetam—Pilot study. Epilepsy Res

2015; 114:52-8.

9. Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM,

Barsan W, Cloyd J, Lowenstein D, et al. Randomized trial of

three anticonvulsant medications for status epilepticus. N

Engl J Med. 2019;381:2103-13.

10. Dalziel SR, Borland

ML, Furyk J, Bonisch M, Neutze J, Donath S, et al.

Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of

convulsive status epilepticus in children (ConSEPT): an

open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet

2019;393:2135-45.

11. Ýþgüder R, Güzel O, Ceylan G,

Yýlmaz Ü, Aðýn H. A comparison of intravenous levetiracetam

and valproate for the treatment of refractory status

epilepticus in children. J Child Neurol. 2016;31:1120-6.

12. Yasiry Z, Shorvon SD. The relative effectiveness of

five antiepileptic drugs in treatment of

benzodiazepine-resistant convulsive status epilepticus: a

meta-analysis of published studies. Seizure. 2014;23:167-74.

13. Brigo F, Bragazzi N, Nardone R, Trinka E. Direct and

indirect comparison meta-analysis of levetiracetam versus

phenytoin or valproate for convulsive status epilepticus.

Epilepsy Behav. 2016;64:110-5.

14. Mehta V, Singhi

P, Singhi S. Intravenous sodium valproate versus diazepam

infusion for the control of refractory status epilepticus in

children: A randomized controlled trial. J Child Neurol.

2007;22:1191-7.

15. Mishra D, Sharma S, Sankhyan N,

Konanki R, Kamate M, Kanhere S, et al. Consensus guidelines

on management of childhood convulsive status epilepticus.

Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:975-90.

16. Dawrant J, Pacaud

D. Pediatric hypocalcemia: making the diagnosis. CMAJ.

2007;177:1494-7.

|

|

|

|

|