|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56:205-208 |

|

Parental Education,

Children’s Nutritional Status and Non-verbal Intelligence in

Rural School-children

|

|

Rubina Mandlik, Veena Ekbote, Shashi Chiplonkar,

Vaman Khadilkar and Anuradha Khadilkar

From Hirabai Cowasji Jehangir Medical Research

Institute, Jehangir Hospital, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Anuradha Khadilkar, Department

of Pediatrics, Hirabai Cowasji Jehangir Medical Research Institute,

Jehangir Hospital, 32 Sassoon Road, Pune 411 001, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: October 12, 2017;

Initial review: March 03, 2018;

Accepted: January 19, 2019.

|

Objective: To assess non-verbal intelligence and

its relationship with nutritional status, nutrient intakes and parents’

education in school-children. Methods: A cross-sectional,

observational study was conducted in children between 6-11 years,

without any known chronic disorder or intellectual disability. Data were

collected regarding parents’ education, anthropometry and dietary

intakes. Non-verbal intelligence was assessed by Raven’s Coloured

Progressive Matrices (RCPM). Results: In 323 enrolled children

(52.9% boys), a significant positive association was observed between

RCPM scores and parents’ education (father’s rs=0.14, mother’s

rs=0.22), height Z-scores (rs=0.14) and dietary intakes of

zinc (rs=0.14), iron (rs=0.12) and folate (rs=0.14).

Conclusion: Height in normal range, higher zinc, iron and

folate intakes, and parental higher educational levels were associated

with higher non-verbal intelligence scores.

Keywords: Cognitive function, Micronutrients, Raven’s Coloured

Progressive Matrices.

|

|

P

arental education and child’s nutritional status

are hypothesized to be major factors that affect a child’s cognitive

abilities [1,2]. Majority of the Indian population (70%) resides in

rural areas where literacy rates are as low as 68.9% [3]. The

nutritional status of children in rural areas has been reported to be

poor with high prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies [4]. Indian

studies suggest that poor cognitive development is related to poor

growth and low socio-economic status [2]. However, there are few reports

that have studied the relationship between cognitive development of

Indian children with micronutrient intake and their parents’ education.

Non-verbal intelligence indicates the ability to

learn, analyze, comprehend, and solve novel, complex problems without

the use of words [5]. Assessment tools like the Raven’s Coloured

Progressive Matrices (RCPM) are preferred in multicultural settings or

rural areas where poor language skills are a barrier [5].

The objectives of this study were to assess the

non-verbal intelligence in school-children from a rural setting and to

study the relationship of nutritional status, nutrient (zinc, iron and

folate) intakes and parents’ education with children’s non-verbal

intelligence.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out in 6-11

year old children from a randomly selected primary school in Karegaon, a

rural area in Western Maharashtra, from mid June 2014 to end of July

2014. Children with known chronic disorders like diabetes, thalassemia

and intellectual disability were excluded [6]. According to earlier

reports of RCPM scores (70.65% children below average), considering a 4%

margin of error and 5% significance level, sample size of 313 was

computed [2]. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee,

Jehangir Clinical Development Centre. Written informed consent was

obtained from parents.

Demographic data, socioeconomic status (SES) and

parents’ education were elicited by structured questionnaires [7].

Height, weight and hemoglobin concentrations were assessed by standard

techniques [8,9]. Anemia was categorized as mild (hemoglobin 11-11.4 g/dL)

and moderate (hemoglobin 8.0-10.9 g/dL) [9].

Clinical psychologists administered the RCPM test.

This measures the general ability of children aged 4 to 11 years, by 3

sets of "diagrammatic puzzles" (12 items in each), with increasing

levels of difficulty [5]. It takes about 15 minutes to administer the

test. Categorization of RCPM scores is as follows: Superior and High

Average (111-130), Average (91-110), Low Average (81-90), Borderline

(71-80) and Extremely Low ( £70)

[5].

Dietary intake was assessed by 24-hour dietary recall

taken over three non-consecutive days. Nutrient intakes were estimated

by the C-Diet software (a cooked foods database software) and were

compared to the Indian recommended dietary allowances (RDA) [10,11].

Dietary adequacy was computed based on Indian RDA.

SPSS for Windows (version 21.0.2012) was used for

statistical analyses. Normality of variables was tested using one-sample

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Chi-square test was used to test the

relationship between the categorical variables. Spearman’s Rank

correlation coefficient (r s)

was used to denote correlation between variables.

Results

The study population comprised of 323 children (52.9%

boys) with mean age of 8 (1.1) years and 89% belonging to middle SES.

Anthropometric parameters and nutritional intakes were comparable and

diets were deficient in both macronutrients and micronutrients. Mild

anemia was detected in 2.3% and moderate anemia in 4.5% children.

Table I depicts the distribution of RCPM scores and

inter-category comparison of demographics.

TABLE I Demographic Characteristics of Children According to the RCPM Scores

|

Parameters |

Superior and High |

Average |

Low Average |

Borderline |

Extremely |

|

Average (111 to 130) |

(91 to 110) |

(81 to 90) |

(71 to 80) |

Low(£70) |

|

n |

11 |

81 |

77 |

79 |

75 |

|

Gender |

|

Male |

73% |

49% |

53% |

54% |

52% |

|

Female |

27% |

51% |

47% |

46% |

48% |

|

Socio-Economic Status |

|

Low SES |

- |

3% |

6% |

8% |

8% |

|

Middle SES |

82% |

92% |

90% |

86% |

92% |

|

High SES |

18%# |

5% |

4% |

6% |

- |

|

Father’s Education |

|

High School and Above |

73% |

80% |

78% |

65%* |

63%* |

|

Lesser than High School |

27% |

20% |

22% |

35%* |

37%* |

|

Mother’s Education |

|

High School and Above |

55% |

56% |

42% |

44% |

24%# |

|

Lesser than High School |

45% |

44% |

57% |

56% |

76%# |

|

*Significantly different from ‘Average’ RCPM score; #Significantly different from other score categories. |

Children, whose parents had completed high school

education or more, attained significantly better scores compared to

children whose parents had lower education levels. Significant positive

associations, but with low correlation coefficients, were found between

both father’s (r s=0.14)

and mother’s (rs=0.22)

education and children’s RCPM score categories.

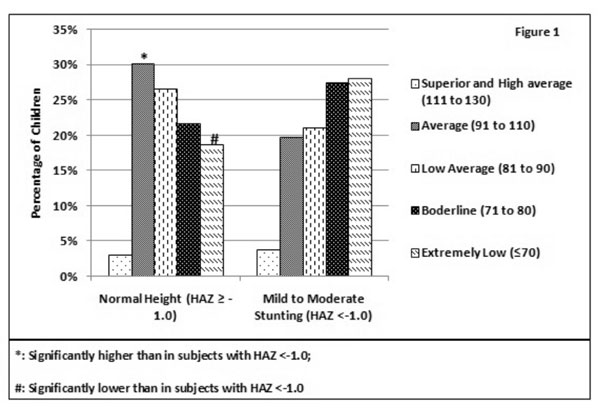

A significantly greater proportion of children (30%)

with normal heights (HAZ ³–1.0)

attained ‘Average’ RCPM scores compared to children (20%) with mild to

moderate stunting (HAZ<–1.0). The percentage of children with ‘Extremely

Low’ scores was lower among children with normal heights (19%) compared

to those with mild to moderate stunting (28%) (Fig. 1).

Similar trends, which were non-significant (P>0.05), were noted

between WAZ and RCPM scores.

|

|

Fig. 1 Association of height-for-age

z-scores with RCPM standard scores.

|

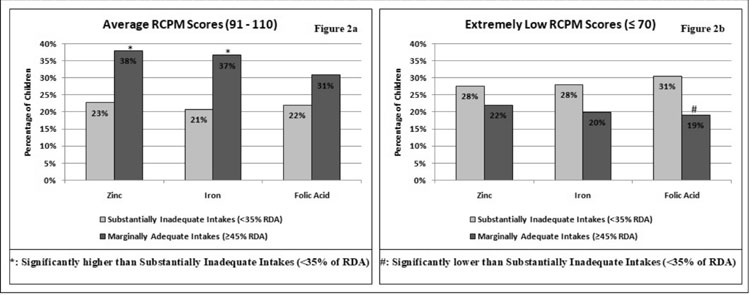

Significant, positive though weak correlations were

obtained for zinc (r=0.14), iron (r=0.12) and folate (r=0.14)

intakes with RCPM scores. These correlations were investigated further

by categorizing micronutrient intakes according to tertiles generated

from the data into 3 groups: substantially inadequate intakes (<35% of

RDA), marginally inadequate intakes (35 to 44% of RDA) and marginally

adequate intakes (³45%

of RDA); and exploring their associations with RCPM categories. A

greater percentage of children, who had marginally adequate intakes of

zinc (38%), iron (37%) and folate (31%) separately, scored ‘Average’

RCPM scores compared to children who had substantially inadequate

intakes of zinc (23%), iron (21%) and folate (22%) (Fig. 2a).

Also, among the children with marginally adequate intakes, the

percentage of children who scored ‘Extremely Low’ RCPM scores were

lesser compared to children with substantially inadequate intakes of

zinc, iron and folate (Fig. 2b).

|

| (a) |

(b) |

|

Fig. 2 Comparison of percentage of

children with ‘Average’ (a), and extremely low (b) RCPM Scores

among micronutrient intake categories.

|

Discussion

This observational study in 6-11 year old children

from a single school in a rural area reveals that majority of children

had below average scores (£90)

in non-verbal intelligence measured by RCPM. Significant positive

associations were found between parents’ education, children’s height

(indicator of nutritional status) and intakes of iron, zinc and folate

with RCPM scores.

Comparably, in a study of Santal tribal children,

RCPM scores of well-nourished children as well as of those from upper

SES were found to be significantly higher than that of the poorly

nourished children and those from lower SES, respectively [2]. The

absence of association of RCPM scores with SES in our study can be

explained by the relatively homogeneous socio-economic status

distribution. However, we did observe positive though weak associations

of paternal and maternal education with RCPM scores, with the latter

demonstrating a stronger association. Schooling, more than household

wealth, has been proposed to be a reliable assessment of SES and

maternal schooling has been demonstrated to exert a strong influence on

children’s cognitive functions [1]. The weak associations obtained

between parental education and RCPM scores may be because other than

parental education level, data related to important factors like

parenting style and family interactions, which also have an influence on

cognitive outcomes, was not collected by us.

It has also been demonstrated in previous studies in

children that micronutrient intakes are positively associated with

cognitive test scores. We observed that though diets of the study

children were overall deficient in micronutrients, those whose diets had

relatively higher amounts of zinc, iron and folate performed better in

RCPM test. Sen, et al. [12] demonstrated that anemia

negatively affected cognition in Indian adolescent girls and

demonstrated an improvement in assessment scores with iron-folic acid

supplementation. Serum folate levels have shown weak significant

positive associations with cognitive test scores in the NHANES III data

on 6-16 year olds [13]. Supplementation studies with zinc-rich foods

have demonstrated positive effects on cognition in young, undernourished

Indian adolescent girls [14]. However, we found poor associations of

micronutrient intakes with RCPM scores in our study; this may possibly

be because current dietary intakes may not have an association with

long-term outcomes such as cognition.

This study being an observational study, only

provides an insight into limited factors that are associated with

non-verbal intelligence in school-children from a rural setting. Further

studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms of association of

different variables observed in this study with non-verbal intelligence

in school-children. Also, long-term supplementation studies which

consider factors such as parenting and family interactions are required.

Thus, in rural school-children, parent’s, especially

mother’s education, children’s linear growth and dietary intakes of

zinc, iron and folate may be important influencers of outcomes in

non-verbal tests of intelligence.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful for the help

and support of Neha Kajale and Sonal Palande. We are thankful to all the

psychologists who administered the Raven’s CPM test and assisted with

its interpretation. We also wish to thank the school principals,

teachers and school staff.

Contributors: RM: data collection, analyses and

drafted the initial manuscript; VHE: assisted with data collection, data

analysis and manuscript revisions; SAC: conceptualized and designed the

study, carried out the analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript,

and approved the final manuscript as submitted; VVK: conceptualized and

designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the

final manuscript as submitted; AVK: conceptualized and designed the

study, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final

manuscript as submitted. All authors approved the manuscript, are

accountable for all aspects.

Funding: Rubina Mandlik was funded by a

fellowship grant from the University Grants Commission (UGC), Government

of India.

Competing interest: None stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

•

Majority (72%) of the 6-11 year-old children from rural setting

had ‘Low Average’ or lower scores (i.e.<90) in non-verbal

intelligence tests.

• Maternal education status, child’s

linear growth and dietary intakes of iron, zinc and folic acid

demonstrated significant, positive but weak associations with

children’s RCPM scores.

|

References

1. Crookston BT, Forste R, McClellan C, Georgiadis A,

Heaton TB. Factors associated with cognitive achievement in late

childhood and adolescence: The Young Lives cohort study of children in

Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:253.

2. Chowdhury DS, Ghosh T. Nutritional and

socioeconomic status in cognitive development of Santal children of

Purulia district, India. Ann Hum Biol. 2011;38:188-93.

3. Government of India. Census of India 2011: Rural

Urban distribution of population. Ministry of Home Affairs Government of

India. 2011 Available from:

http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/paper2/data_files/india/Rural_Urban_2011.pdf.

Accessed May 20, 2018.

4. Laxmaiah A, Arlappa N, Balakrishna N, Mallikarjuna

Rao K, Galreddy C, Kumar S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of

micronutrient deficiencies among rural children of eight states in

India. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;62:231-41.

5. Raven J. Coloured Progressive Matrices and

Crichton Vocabulary Scale India Edition. Bengaluru: NCS Pearson (India)

Pvt Ltd; 2004. p. 1-99.

6. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, Virginia, USA: American Psychiatric

Association; 2013.

7. Kumar N, Shekhar C, Kumar P, Kundu A. Kuppuswamy’s

socioeconomic status scale-updating for 2007. Indian J Pediatr.

2007;74:1131-2.

8. Khadilkar V, Yadav S, Agrawal K, Tamboli S,

Banerjee M, Cherian A, et al. Revised IAP growth charts for

height, weight and body mass index for 5-18-year-old Indian children.

Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:47-55.

9. World Health Organization. Haemoglobin

concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity.

In: Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. 2011. p.

1-6.

10. Chiplonkar S. CDiet – Bellycheaters. Available

from: https://bellycheaters.com/cdiet/. Accessed October 05,

2018.

11. Indian Council of Medical Research. Nutrient

Requirements and Recommended Dietary Allowances for Indians. ICMR: New

Delhi; 2009. p. 1-334.

12. Sen A, Kanani SJ. Impact of iron-folic acid

supple-mentation on cognitive abilities of school girls in Vadodara.

Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:137-43.

13. Nguyen C, Gracely E, Lee B. Serum folate but not

vitamin B-12 concentrations are positively associated with cognitive

test scores in children aged 6–16 years. J Nutr. 2013;143:500.

14. Tupe RP, Chiplonkar SA. Zinc supplementation

improved cognitive performance and taste acuity in Indian adolescent

girls. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28:388-96.

|

|

|

|

|