|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:206-210 |

|

Effect of Gastric

Lavage on Meconium Aspiration Syndrome and Feed Intolerance in

Vigorous Infants Born with Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid –

A Randomized Control Trial

|

|

Shrishail Gidaganti, MMA Faridi, Manish Narang and

Prerna Batra

From Division of Neonatology, Department of

Pediatrics, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur

Hospital, Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr MMA Faridi, Flat # G-4, Plot #

14, Block-B, Vivek Vihar Delhi 110 095, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: April 17, 2017;

Initial review: June 20, 2017;

Accepted: January 03, 2018.

Trial Registration: CTRI/2014/03/004495

|

Objective: To compare the incidence of meconium aspiration syndrome

and feed intolerance in infants born through meconium stained amniotic

fluid with or without gastric lavage performed at birth.

Setting: Neonatal unit of a teaching hospital in

New Delhi, India.

Design: Parallel group unmasked randomized

controlled trial.

Participants: 700 vigorous infants of gestational

age ³34

weeks from through meconium stained amniotic fluid.

Intervention: Gastric lavage in the labor room

with normal saline at 10 mL per kg body weight (n=350) or no

gastric lavage (n=350). Meconiumcrit was measured and expressed

as £30%

and >30%.

Outcome Measures: Meconium aspiration syndrome,

feed intolerance and procedure-related complications during 72 h of

observation.

Results: 5 (1.4%) infants in lavage group and 8

(2.2%) in no lavage group developed meconium aspiration syndrome (RR

0.63, 95% CI 0.21, 1.89). Feed intolerance was observed in 37 (10.5%)

and 53 infants (15.1%) in lavage and no lavage groups, respectively (RR

0.70, 95% CI 0.47, 1.03). None of the infants in either group developed

apnea, bradycardia or cyanosis during the procedure.

Conclusion: Gastric lavage performed in the labor

room does not seem to reduce either meconium aspiration syndrome or feed

intolerance in vigorous infants born through meconium stained amniotic

fluid.

Keywords: Neonate, Prevention, Respiratory distress, Risk

factors, Vomiting.

|

|

Meconium stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) complicates 7%

to 22% deliveries, with meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) developing in

approximately 10% of babies with MSAF [1,2]. Amount of meconium in the

amniotic fluid, fetal acidemia and fetal heart rate are some of the

factors determining the risk of MAS [3,4]. The infant born through MSAF

may ingest or aspirate meconium in utero, during delivery or

after birth. Due to the chemical nature and vasoconstriction action of

the meconium, the MSAF might cause meconium induced gastritis leading to

feed intolerance. After birth, infant may also vomit and aspirate MSAF

resulting in ‘secondary meconium aspiration syndrome’ [5]. Gastric

lavage soon after birth is advocated to prevent these complications.

Some clinicians advise gastric lavage with normal saline but others

advocate use of soda bicarbonate for stomach wash [6-8]. Interestingly,

none of the practices of gastric lavage is based on scientific evidence

and is followed at most centers by convention.

The insertion of infant feeding tube in the stomach

is an invasive procedure and might cause immediate complications like

apnea, bradycardia, cyanosis and traumatic injury and late adverse

effects like impaired sensitivity to pain [6-9]. We, therefore, planned

this study to compare the frequency of MAS and feed intolerance between

the infants born through MSAF with and without gastric lavage performed

in the labor room, and also to evaluate safety of the procedure.

Methods

This parallel group unmasked randomized controlled

trial was conducted in the Division of Neonatology of University College

of Medical Sciences and GTB Hospital, Delhi, India. The study was

approved by the institutional Ethics Committee for Human Research.

Written informed consent was obtained from the mother before delivery.

Assuming proportion of MAS as 15% among those born

with MSAF [10], level of significance 5%, power 80%, and 50% relative

difference of MAS in infants with or without gastric lavage, a sample

size of 700 infants (350 in each group) was calculated to be sufficient.

Study participants included neonates of both genders with gestational

age ³34 weeks,

who were born through MSAF and were vigorous at birth. Babies with gross

congenital anomalies, those born to mothers with suspected

chorioamnionitis, and those receiving methyldopa during pregnancy were

excluded from the study. The gestational age was calculated by Naegle’s

rule and Modified Ballard’s scoring [11]; latter was taken into account

if difference in the gestational age estimated by two methods was

greater than two completed weeks.

Eligible newborns were randomized through computer

generated random numbers to assign them into intervention (lavage) or

control group. Coding scheme was concealed in serially numbered, opaque,

and sealed envelopes by a person not directly involved in the study.

Parents were informed of the group, their infant was included in, after

randomization.

About 15 mL MSAF was obtained in a clean kidney tray

with the help of a sterilized plain rubber catheter No.10 passed through

vagina or directly in the kidney tray during delivery. In cases of

caesarean section, liquor was collected in a 20 mL disposable syringe by

an obstetrician after giving uterine incision. Meconiumcrit was assessed

by centrifuging 10 mL MSAF at 1000 rpm for 10 min in a 20 mL glass test

tube.

The infant was placed under radiant warmer. Oxygen

sensor of the Pulse Oximeter (Welch Allyn, USA) was attached to the

ulnar aspect of the right wrist. After initial stabilization in the

labor room, gastric lavage was carried out in the intervention group. An

orogastric tube (#10 Fr) was passed into the stomach, after measuring

the length as per the standard procedure, and lavage was done with

normal saline (10 mL/kg body weight). In control group, gastric lavage

was not performed. The heart rate, oxygen saturation, apnea and color of

the infant were monitored during gastric lavage and till 20 min after

removal of orogastric tube. In control group also, above parameters were

recorded for same the duration. Heart rate <120 bpm and >160 bpm were

taken as bradycardia and tachycardia respectively. Apnea was defined as

cessation of breathing for >20 sec or for any duration associated with

cyanosis or bradycardia. SpO 2

< 85% after 15 min of birth was taken as significantly low. Local trauma

to the oropharynx was assessed by naked eye examination twice in first

12 h of life. Breastfeeding was started within 60 min after normal

delivery and within two hours after caesarean section. X-ray

chest was obtained within 4 h in all infants, and was repeated if infant

developed respiratory distress.

The respiratory distress was monitored by Downe’s

score at birth [13] and repeated every 6 h for first 24 h, and every 12

h for next 48 h. When Downe’s score was

³3 a repeat X-ray

chest was obtained and MAS was treated as per standard treatment

protocol. MAS was defined as the presence of respiratory distress in an

infant born through MSAF, whose symptoms could not be otherwise

explained and with radiological evidence of meconium aspiration [14].

Intolerance to enteral feeding was evaluated one hour after initiation

of breastfeeding and every six hour thereafter for 72 h. Feed

intolerance was considered if there was history of vomiting at least two

times in 24 h, or there was pre-feed aspirate of >50% of previous feed

even once in 24 h in case baby was fed expressed breast milk by

orogastric tube, or increase in abdominal girth by 2 cm on two occasions

in 24 h. Vomiting was differentiated from regurgitation by the

associated features like retching/ tachycardia/ salivation/ sweating

[15]. When a baby developed feed intolerance, gastric lavage was carried

out with normal saline if it was not done earlier; weight and urine

output were monitored and breastfeeding was continued as per the unit

protocol. In case infant continued with feed intolerance after 24 h, a

repeat gastric lavage was done with the normal saline and breastfeeding

was continued.

Primary outcome measure was proportion of infants

developing meconium aspiration syndrome within 72 h of age in both

groups. Secondary outcome measures were proportion of infants developing

feed intolerance after initiation of breastfeeding till 72 h in two

groups and number of babies showing adverse effects of gastric lavage

(apnea, bradycardia, cyanosis, local trauma).

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed by SPSS

16.0 statistical software. Meconiumcrit was compared in two groups by

Student’s ‘t’ test. The comparison of the qualitative variables such as

MAS and feed intolerance in the study and control groups were done using

Chi square test. P value of <0.05 was considered as statistically

significant.

Results

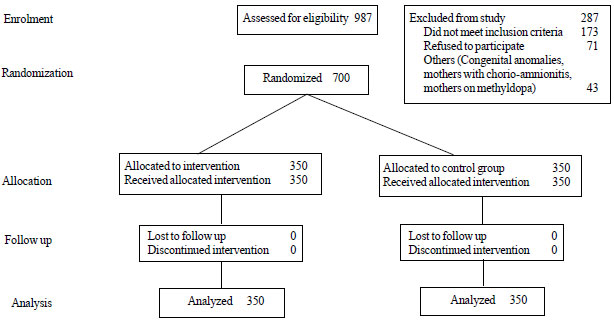

A total of 700 infants (350 each in intervention and

control group) were enrolled and successfully completed the study (Fig.

1). The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of

enrolled infants are presented in Table I.

TABLE I Comparison of Perinatal and Neonatal Parameters in Study and Control Groups

|

Variables |

Intervention |

Control group |

|

group (n=350) |

(n=350) |

|

Perinatal Characteristics |

|

Primipara |

190 (54.3) |

185 (52.9) |

|

Meconiumcrit |

|

|

|

≤30% |

249 (71.1) |

260 (74.3) |

|

>30% |

101 (28.9) |

90 (25.7) |

|

Fetal bradycardia |

46 (13.1) |

41 (11.7) |

|

Fetal tachycardia |

16 (4.6) |

14 (4.0) |

|

Caesarian delivery |

129 (36.9) |

109 (31.1) |

|

Forceps/ Vacuum |

5 (1.4) |

6 (1.7) |

|

Breech |

8 (2.3) |

3 (0.9) |

|

APGAR Score* |

|

1 min |

8.9 (0.3) |

8.9 (0.3) |

|

5 min |

9.0 (0.3) |

9 (0.3) |

|

Neonatal Characteristics |

|

Male gender |

182 (52.0) |

193 (55.1) |

|

Preterm birth |

94 (26.9) |

97 (27.4) |

|

Birth weight (g)* |

2684 (398) |

2706 (398) |

|

Length (cm)* |

48.1 (1.4) |

48.2 (1.4) |

|

Head circumference (cm)* |

33.5 (0.8) |

33.6 (0.8) |

|

Values in No. (%) or *mean (SD). |

|

|

Fig. 1 Consort flow diagram for the

study.

|

A significant difference was noted in number of

vomiting episodes in first 24 hours (P=0.001), while no

statistical difference was noted in incidence of MAS and feed

intolerance in the two groups (Table II). Gastric lavage

prevented occurrence of first episode of vomiting within 6 hour of

initiation of breastfeeding but did not affect eventual development of

feed intolerance. Overall, feed intolerance developed in 90 (12.8%)

infants after initiation of breastfeeding. However, all infants improved

after 48 h of age (Table III). Out of 90 infants who

suffered from feed intolerance, 63 (70%) were born with meconiumcrit

£30%, and in

27 (30%) babies, the meconiumcrit was >30% (P>0.05).

TABLE II Effect of Gastric Lavage on Development of Meconium Aspiration Syndrome and Feed Intolerance

|

Outcome |

Intervention group (n=350), No.(%) |

Control group (n=350), No.(%) |

RR (95% CI) |

|

Meconium aspiration syndrome |

5 (1.4) |

8 (2.2) |

0.63 (0.21, 1.89) |

|

Feed Intolerance |

37 (10.5) |

53 (15.1) |

0.70 (0.47, 1.03) |

|

Vomiting episodes in 24 h |

76 |

115 |

0.66 (0.52, 0.85) |

|

0-6 h |

30 (8.5) |

47 (13.4) |

0.64 (0.41, 0.96) |

|

6-12 h |

32 (9.1) |

38 (10.8) |

0.84 (0.54, 1.32) |

|

12-24 h |

14 (4) |

30 (8.5) |

0.47 (0.25, 0.86) |

|

Vomiting episodes in 24-48 h |

6 (1.7) |

10 (2.8) |

0.38 (0.15, 0.95) |

No baby developed apnea, bradycardia or local trauma

in the study group; SpO2 <

85% at 15 min was observed in one baby in the control group and two

babies in the intervention group (P>0.05).

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial on vigorous

infants born through meconium stained amniotic fluid, we documented that

gastric lavage performed immediately after birth in labor room did not

reduce the incidence of MAS and feed intolerance. No procedure related

complication was observed following gastric lavage.

Investigators could not be blinded for intervention

due to the nature of intervention, and results cannot be generalized on

non-vigorous infants, constitute few study limitations. Also, the study

was not adequately powered to detect smaller changes in the incidence of

MAS and feeding intolerance.

In a similar study from India, Sharma, et al.

[6] randomized 267 babies in gastric lavage and 269 babies to no gastric

lavage group. They followed up infants for development of retching,

vomiting and secondary meconium aspiration syndrome till the time they

were discharged from the hospital. None of the babies developed

secondary meconium aspiration syndrome in any group [6]. Evidence from

several other studies also does not support gastric lavage preventing

feed intolerance in infants born with MSAF [5,7,15-17]. A recent

systematic review by Deshmukh, et al. [18] concluded that gastric

lavage may improve feed tolerance in neonates born to MSAF; however

small sample size in included studies, and probable bias were the

limitations. Our study is in conformity with above observations that

routine gastric lavage in MSAF babies does not seem to prevent

development of MAS, irrespective of the concentration of meconium in the

amniotic fluid, mode of delivery or birthweight. Gastric lavage also

does not seem to reduce incidence of feed intolerance either, though the

first episode of vomiting after initiation of breastfeeding may be

prevented. However, the procedure of gastric lavage appears safe,

without immediate complications like apnea, bradycardia, cyanosis or

local trauma. We recommend further studies addressing the issue of MAS

and feed intolerance on non-vigorous infants to generate stronger

evidence in favor or against gastric lavage performed in the labor room.

Contributors: SG: data collection and

prepared initial draft of manuscript; MMAF: conceptualized study,

analyzed and scrutinized data, and finalized the manuscript; MN:

supervised data collection and contributed to manuscript writing; PB:

reviewed literature, manuscript editing and analysis. All authors

approved final version of the manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

|

What is Already Known?

•

Gastric lavage in infants born through meconium stained

amniotic fluid is performed to prevent secondary meconium

aspiration syndrome and feed intolerance.

What This Study Adds?

•

Gastric lavage in

vigorous infants born through meconium stained amniotic fluid

does not seem to reduce the incidence of meconium aspiration

syndrome or feed intolerance.

|

References

1. Bhat R, Rao A. Meconium-stained amniotic fluid and

meconium aspiration syndrome: a prospective study. Ann Trop Paediatr.

2008;28:199-203.

2. Narang A, Nari PMC, Bhakoo ON. Management of

meconium stained amniotic fluid: A team approach. Indian Pediatr.

1989;30:9-13.

3. Trimmer KJ, Gilstrap LC 3rd. "Meconiumcrit" and

birth asphyxia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1010-3.

4. Rossi EM, Philipson EH, Williams TG, Kalhan SC.

Meconium aspiration syndrome: intrapartum and neonatal attributes. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 1989; 161:1106-10.

5. Sharma P, Nangia S, Tiwari S, Goel A, Singla B,

Saili A. Gastric lavage for prevention of feeding problems in neonates

with meconium stained amniotic fluid : A randomized controlled trial.

Peditar Int Child Health. 2014;34:115-9.

6. Narachi H, Kulayat N. Is gastric lavage needed in

neonates with meconium-stained amniotic fluid? Eur J Pediatr.

1999;158:315-7.

7. Ameta G, Upadhyay A, Gothwal S. Role of gastric

lavage in vigorous neonates born with meconium stained amniotic fluid.

Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:195-8.

8. Anand KJS, Runeson B, Jacobson B. Gastric suction

at birth associated with long term risk for functional intestinal

disorders in later life. J Pediatr. 2004;144:449-54.

9. Stoll B. The Newborn Infant. In: Kliegman

R, Jenson H, Behrman R, Stanton B. editors, Nelson’s Textbook of

Pediatrics (18thed). Saunders Elsevier Publications India. 2008. p.

675-83.

10. Bahl D. A Study of Neonatal Outcome in Relation

to Meconiumcrit of Liquor Amnii. MD Thesis, University of Delhi, 1993.

11. Ballard JL, Khoury JC, Wedig K, Wang L, Eilers-Walsman

BL, Lipp R. New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature

infants. J Pediatr. 1991; 119:417-23.

12. Bhat S. Respiratory distress in newborns In:

Achar’s textbook of Pediatrics, 4th ed. Universities Press; 2009. p.

221.

13. Wiswell TE, Bent RC. Meconium staining and the

meconium aspiration syndrome: Unresolved issues. Pediatr Clin N Am.

1993;50:955-81.

14. JeevaSankar M, Agarwal R, Mishra S, Deorari AK,

Paul VK. Feeding of low birth weight infants. Neonatology protocols.

Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75:459-69.

15. Shah L, Shah GS, Singh RR, Pokharel H, Mishra OP.

Status of gastric lavage in neonates born with meconium stained amniotic

fluid: A randomized controlled trial. Italian J Pediatr. 2015;41:85.

16. Garg J, Masand R, Tomar BS. Utility of gastric

lavage in vigorous neonates delivered with meconium stained liquor: A

randomized controlled trial. Int J Pediatr. 2014;2014:204807.

17. Cuello-García C, González-López V, Soto-González

A.Gastric lavage in healthy term newborns: A randomized

controlled trial. Ann Pediatr (Barc). 2005;63:509-13.

18. Deshmukh M, Balasubramanian H, Rao S, Patole S.

Effect of gastric lavage on feeding in neonates born through meconium-stained

liquor: A systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed.

2015;100:F394-9.

|

|

|

|

|