|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2017;54: 215-221 |

|

Accuracy of Tactile Assessment of Fever in

Children by Caregivers:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

|

|

Yan-Wei Li, Le-Shan Zhou and Xing Li

From Nursing department, Tongji Hospital, Tongji

Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan,

China

Correspondence to: Le-Shan Zhou, Professor, Xiangya

Nursing School, Central South University, No 172, Tongzipo Road, Yuelu

District, Changsha City, 410013, China. [email protected]

Published online: February 02, 2017.

PII:S097475591600044

|

|

Context: Fever is the most common

complaint in the pediatric and emergency departments. Caregivers prefer

to detect fever in their children by tactile assessment.

Objective: To summarize the

evidence on the accuracy of caregivers’ tactile assessment for detecting

fever in children.

Evidence-acquisition: We

performed a literature search of Cochrane Library, PubMed, Web of

Knowledge, EMBASE (ovid), EBSCO and Google Scholar, without restriction

of publication date, to identify English articles assessing caregivers’

ability of detecting fever in children by tactile assessment. Quality

assessment was based on the 2011 Quality Assessment of Diagnostic

Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) criteria. Pooled estimates of sensitivity

and specificity were calculated with use of bivariate model and summary

receiver operation characteristics plots for meta-analysis.

Results: 11 articles were

included in our analysis. The summary estimates for tactile assessment

as a diagnostic tool revealed a sensitivity of 87.5% (95% CI 79.3% to

92.8%) and specificity of 54.6% (95% CI 38.5% to 69.9%). The pooled

positive likelihood ratio was 1.93 (95% CI 1.39 to 2.67) and negative

likelihood ratio was 0.23 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.36). Area under curve was

0.82 (95% CI 0.7 to 0.85). The pooled diagnostic odds ratio was 8.46

(95% CI 4.54 to 15.76).

Conclusion: Tactile assessment of

fever in children by palpation has moderate diagnostic value.

Caregivers’ assessment as "no fever" by touch is quite accurate in

ruling out fever, while assessment as "fever" can be considered but

needs confirmation

Keywords: Assessment, Measurement, Parents and

Pyrexia.

|

|

F

ever is the most common complaint

in the pediatric out-patient and emergency departments, accounting for

almost one-third of these visits [1,2]. Fever is a vital symptom for

diagnosis. In a child, many infections disease either single or in

combination could present with fever [3]. Although thermometers are

readily available at home, parents still prefer to detect fever by

touch. A study from New York revealed that although 78% parents owned a

thermometer at home, 48% still used palpation as the usual method to

detect fever, and up to 87% of parents used palpation at least

occasionally [4], similar to that reported by other authors [5,6]. It is

a fact that tactile assessment of fever by palpation is universal due to

its convenience.

The initial diagnosis of fever in a child is based

almost entirely on the assessment by the caregivers [7]. The ability of

caregivers to detect fever accurately in children by tactile examination

is critical in preventing a first stage delay in the management of

childhood illnesses [8]. The World Health Organization and United

Nations Children’s Fund assume that mothers are able to assess their

children by palpation for the presence of fever [9]. However, it is

controversial about whether caregivers have the ability to accurately

evaluate their children’ body temperature. Some studies suggest that

there are significant inaccuracies in tactile assessment of body

temperature, and objective measurement of temperature is recommended

[8-10]. While findings in other studies showed that caregivers were able

to provide accurate information about the presence or absence of fever

in their children by palpation without the use of a thermometer [11-13].

Therefore, tactile assessment could be accept as a reliable screening

tool for fever determination, and caregivers’ description of their

children’ history of fever should be considered when giving medical

decisions [11-13].

Teng, et al. [10] conducted a systematic

review in 2007 about the accuracy of mother’s touch to detect fever in

children. Many new studies have since been published in the topic. We,

therefore, conducted this updated systematic review on the accuracy of

palpation by caregiver to detect fever.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the

guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta

Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [14].

Search Strategy

We searched the databases of Cochrane Library, Pub

Med, Web of knowledge, EMBASE (Ovid), EBSCO and Google Scholar for

diagnostic studies in English comparing tactile assessment of fever with

objective method using a thermometer, without date restrictions. We used

the following search terms: child or children, fever or febrile, palpate

or palpation or touch or tactile or subjective assesment. Hand-search

was performed after screening the reference lists of the retrived

articles for pertinent publications. Abstracts were reviewed and

full-text articles were obtained for studies that met the eligibility

criteria.

Study Selection

Inclusion criteria: (a) published original

papers in English; (b) evaluated the accuracy of palpation by

parents as a method of detecting fever in children, compared with

thermometer measurement; and (c) provided detailed information on

the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and

negative predictive value (NPV) of tactile assessment. We contacted the

corresponding authors to obtain missing information when necessary.

Exclusion criteria: (a) tactile assessment

was not done during the study, which means tactile assessment was done

at a different time and could not be compared against thermometer

measurement at the same time; (b) publication with only title and

abstract, and full text could not be obtained after contacting the

corresponding authors twice; and (c) duplications, letters and

reviews.

Data were extracted independently through a

standardized protocol by two reviewers. Disagreements between the two of

them were recorded and resolved by consultation with a third author. We

recorded characteristics of the study (author, design, year of

publication, study country, and setting), study population (sample size,

age range, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and prevalence of fever),

reference standard (axillary temperature or rectal temperature or

others, diagnostic cut-off), and index tests (definition, procedures,

and link with inclusion criteria) on predefined forms. The diagnostic

performance measure for index tests: sensitivity, specificity, positive

predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive

likelihood ratio (–LR), negative likelihood ratio (–LR) were also

collected.

Quality Assessment

We assessed the quality of selected studies and

potential risk of bias with the 2011 revised version of the Quality

Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2), adapted to the

review diagnostic accuracy studies, as recommended by the Cochrane

Collaboration. This tool is composed of four domains that consider

patient selection, index test, reference standard and flow of patients

through the study, and timing of the index tests [15]. The quality

assessment was done independently by two authors. Any disagreement was

resolved through discussion and consensus.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA

software version12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Bivariate binomial mixed model was chosen and computed using the Midas

program, as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration for meta-analysis

of diagnostic accuracy studies [16]. Meta-analytic integration of

appointed studies was used for pooled estimated sensitivity, pooled

estimated specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood

ratio, diagnostic odds ratio and variations (Chi-square, I-square, LRT

p) for heterogeneity assessment. A summary receiver operating

characteristic (SROC) curve was drawn to identify diagnostic performance

of tactile assessment from the area under the curve (AUC). Publication

bias was explored using Egger’s test and Funnel plots.

Results

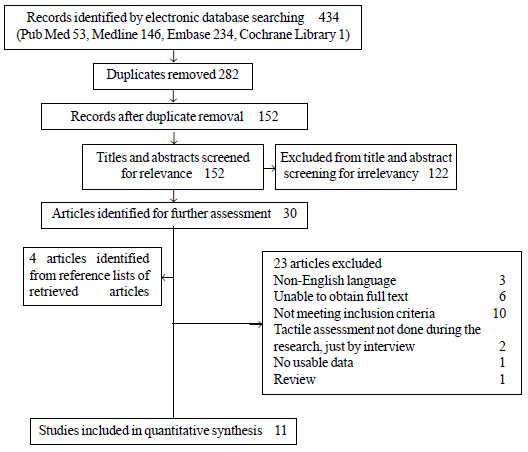

The study selection process is displayed in Fig.

1. Eleven full-text articles [4,10,13,17-24] were included in the

quantitative study and underwent quality assessment using QUADAS-2(http://www.bristol.ac.uk/social-community-medicine/projects/quadas/quadas-2/).

Table I summarizes the characteristics of the included

studies. The 11 included studies were conducted in various

countries/regions in the world and included a total of 3,625 children.

Major variations in sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value,

negative predictive value existed in these studies Table II.

|

|

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the study

selection process.

|

TABLE I Characteristics of Included Diagnostic Studies

|

|

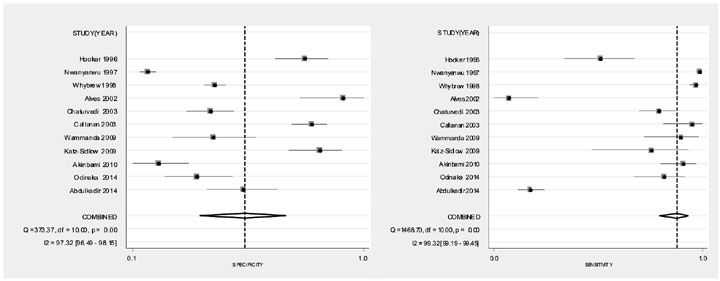

Fig. 2 Forest plot for sensitivity and

specificity of tactile assessment.

|

Quality assessment: Risk of bias and

applicability of the included studies are displayed in Table

III. Overall the 11 studies were rated with an average acceptable

applicability. The majority of the included studies were at low risk for

two categories with respect to applicability, including the patient and

index test. Most studies used convenience samples, leading to high risk

of bias in the patient section domain.

TABLE II The Diagnostic Parameters of Tactile Assessment in the Included Studies

|

Studies |

TP/n |

FP/n |

FN/n |

TN/n |

Sen/% |

Spe/% |

PLR |

NLR |

DOR |

|

Abdulkadir, et al. (2014) |

218 |

29 |

128 |

34 |

63.0 |

54.0 |

1.37 |

0.69 |

2.00 |

|

Odinaka, et al .(2014) |

42 |

39 |

9 |

23 |

82.4 |

37.1 |

1.31 |

0.48 |

2.75 |

|

Akinbami, et al. (2010) |

106 |

54 |

6 |

16 |

94.6 |

22.9 |

1.23 |

0.23 |

5.23 |

|

Katz-Sidlow, et al. (2009) |

17 |

12 |

4 |

55 |

81 |

82 |

4.52 |

0.23 |

19.48 |

|

Wammanda, et al. (2009) |

79 |

25 |

3 |

19 |

96.3 |

43.2 |

1.70 |

0.08 |

20.01 |

|

Callanan, et al. (2003) |

21 |

33 |

2 |

123 |

91.3 |

78.8 |

4.32 |

0.11 |

39.14 |

|

Chaturvedi, et al. (2003) |

48 |

75 |

20 |

54 |

70.5 |

40.9 |

1.21 |

0.70 |

1.73 |

|

Alves, et al. (2002) |

104 |

3 |

33 |

29 |

75.9 |

90.6 |

8.10 |

0.27 |

30.46 |

|

Whybrew, et al. (1998) |

221 |

353 |

15 |

273 |

93.6 |

43.6 |

1.66 |

0.15 |

11.39 |

|

Nwanyanwu, et al. (1997) |

399 |

574 |

11 |

136 |

97.3 |

19.2 |

1.20 |

0.14 |

8.59 |

|

Hooker, et al. (1996) |

81 |

19 |

18 |

62 |

81.8 |

76.5 |

3.49 |

0.24 |

14.68 |

Notes: TP: true positive; FP: false positive; TN: true negative; FN: false negative;

Sen: sensitivity; Spe: specificity; PLR: positive likelihood ratio; NLR:negative

likelihood ratio; DOR: diagnostic odds ratio; n: number of children.

|

TABLE III Bias and Applicability: The Relative Level Bias Assessment of Bias Risk and Applicability

Concerns Across the Included Studies

|

Study |

Risk of bias |

Applicability concerns |

|

Patient |

Index |

Reference

|

Flow and |

Patient

|

Index |

Reference

|

|

selection |

test |

standard |

timing |

selection |

test |

standard |

|

Abdulkadir, et al. (2014) |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

|

Odinaka, et al. (2014) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Akinbami, et al. (2010) |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

|

Katz-Sidlow, et al. (2009) |

High |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

|

Wammanda, et al. (2009) |

High |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

|

Callanan, et al. (2003) |

High |

High |

High |

Low |

High |

High |

Low |

|

Chaturvedi, et al. (2003) |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

|

Alves, et al. (2002) |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

|

Whybrew (1998) |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

|

Nwanyanwu, et al. (1997) |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Hooker, et al. (1996) |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Meta-analysis: The pooled sensitivity of

tactile assessment as a method of detecting fever was 87.5% (95% CI

79.3% to 92 8%) and the pooled specificity was 54.6% (95% CI 38.5% to

69.9%). The pooled diagnostic odds ratio was 8.46 (95%CI, 4.54 to15.76).

Significant heterogeneity was found among studies (P<0.001, I 2=99.3).

Forest plot for sensitivity and specificity of

tactile assessment is showed in Fig. 2. The funnel plot

and the test indicates no publication bias (P=0.11).

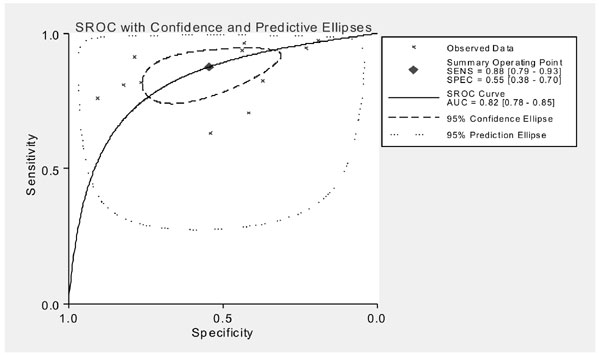

The SROC curve of sensitivity vs. specificity

of tactile assessment suggests diagnostic cut-off located in the point

where sensitivity was 0.88 and specificity 0.55. It also indicates that

there was no threshold effect. Area under curve was 0.82 (95% CI 0.7 to

0.85), predicting moderate diagnostic value (Fig. 3). When

looking at the likelihood ratios (measures that are more meaningful for

clinical decisions), pooled estimates of positive likelihood ratio were

1.93 (95% CI 1.39 to 2.67), and pooled estimates of negative likelihood

ratio were 0.23 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.36).

|

|

Fig. 3 SROC curve of sensitivity

versus specificity of tactile assessment.

|

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis documented

that tactile assessment of fever by caregiver in children had moderate

diagnostic value. The reasonably high sensitivity and low negative

likelihood ratio indicated that caregivers’ assessment of ‘no fever’

were quite accurate. When a child had no fever, the caregiver can

perhaps accurately judge it by palpation. On the other hand, the

specificity and the positive likelihood ratio were not good enough,

meaning thereby that caregivers’ assessment of ‘fever’ was not that

reliable and confirmation was needed. Tactile assessment was therefore

more useful to exclude fever rather than to confirm fever.

There are some limitations of this review. First, six

potentially relevant articles could not be included because of missing

information [25-30]. In the abstract of four of these studies, it was

stated that caregivers’ assessment of fever was reliable [25-27,30] with

relatively high sensitivity. Abstracts of the other two articles could

not be found [28,29]. Second, the quality of the results was moderate to

low. Also there was significant heterogeneity among the chosen studies

for the meta-analysis. Although bivariate binomial mixed model allowing

for heterogeneity was used in our analysis [31], the heterogeneity could

not be eliminated through statistical methods. The heterogeneity was

supposed to be caused by the significant differences in educational

background, severity of pyrexia, age of child, methods of temperature

recording, fever threshold and research design in the included studies.

The results of our study were similar to the findings

of a previous systematic review [10]. The diagnostic odds ratio was

different from that of the earlier review, but the 95% confidence level

was still above one. We added area under curve to indicate diagnostic

value, which is more convincing when the diagnostic cut-off is

different.

As a subjective method, tactile assessment of fever

had not reached a uniform standard so far. There were only few studies

exploring the effect of different palpation method (site used, part of

hand used) on reliability of tactile assessment. Odinaka’s study [17]

revealed that palpation with the palmar surface of the hand using

multiple sites improves the reliability of tactile assessment of fever.

Since detecting fever by touch has some value for reference, we can

explore some techniques to improve the reliability of this method and

carry out relevant education to caregivers.

Contributors: YWL: conceptualized and designed

the study, carried out the analyses, interpreted the data, drafted the

initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted; LSZ:

conceptualized and designed the study, assisted in the interpretation of

the results, revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript

as submitted; XL: assisted in data extraction and the interpretation of

the results, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. Wallenstein MB, Schroeder AR, Hole MK, Ryan C,

Fijalkowski N, Alvarez E, et al. Fever literacy and fever phobia.

Clin Pediatr. 2013;52:254-9.

2. Dai YT, Lu SH. What’s missing for evidence-based

fever management? Is fever beneficial or harmful to humans? Int J Nurs

Stud. 2012;49:505-7.

3. Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB. Nelson

Textbook of Paediatrics. 16 Edition. WB Saunders Company: New York;

2000. p. 2-3.

4. Katz-Sidlow RJ, Rowberry JP, H M. Fever

determination in young infants: prevalence and accuracy of parental

palpation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:12-4.

5. Polat M, Kara S, Tezer H, Tapýsýz A, Derinöz O,

Dolgun A. A current analysis of caregivers’ approaches to fever and

antipyretic usage. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:365-71.

6. Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sweileh WM, Nabulsi MM,

Tubaila MF, Awang R, et al. Beliefs and practices regarding

childhood fever among parents: A cross-sectional study from Palestine.

BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:1-8.

7. Einterz EM, Bates ME. Fever in Africa: Do patients

know when they are hot? Lancet. 1997;350:781.

8. Asekun-Olarinmoye EO, Egbewale BE, Olajide FO.

Subjective assessment of childhood fever by mothers utilizing primary

health care facilities in Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. Niger J Clin

Pract. 2009;12:434-8.

9. Wammanda RD, Onazi SO. Ability of mothers to

assess the presence of fever in their children: Implication for the

treatment of fever under the IMCI guidelines. Ann Afr Med.

2009;8:173-6.

10. Teng CL, Ng CJ, Nik-Sherina H, Zailinawati AH,

Tong SF. The accuracy of mother’s touch to detect fever in children: A

systematic review. J Trop Pediatrics. 2007;54:70-3.

11. Oyakhirome S, Profanter K, Kremsner PG.

Assessment of fever in African children: implication for malaria trials.

Am Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:215-8.

12. Jawad J, Faisal B, Shafique M, Ghafoor T.

Maternal perception of fever in children by tactile technique, How valid

it is? Pak Armed Forces Med J. 2014;64:488-92.

13. Abdulkadir MB, Johnson WB, Ibraheem RM. Validity

and accuracy of maternal tactile assessment for fever in under-five

children in north central Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open.

2014;4:e005776.

14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Group

P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:

the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 151:264-9.

15. Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S,

Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the

quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med.

2011;155:529-36.

16. Macaskill P, Gatsonis C, Deeks J, Harbord R,

Takwoingi Y. Chapter 10: Analysing and Presenting Results. In:

Deeks JJ, Bossuyt PM, Gatsonis C (eds). Cochrane handbook for systematic

reviews of diagnostic test accuracy version 1.0, The Cochrane

Collaboration. 2010. Available from://srdta.cochrane.org.

Accessed January 6, 2014.

17. Odinaka KK, Edelu BO, Nwolisa EC. Accuracy of

subjective assessment of fever by Nigerian mothers in under-5 children.

Niger Med J. 2014;55:338-41.

18. Hooker EA, Smith SW, Miles T, King L. Subjective

assessment of fever by parents: comparison with measurement by

noncontact tympanic thermometer and calibrated rectal glass mercury

thermometer. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:313-7.

19. Nwanyanwu OC, Ziba C, Redd SC, Luby SP. Palpation

as a method of fever determination in Malawian children who are less

than 5 years old: how reliable is it? Ann Trop Med Parasitol.

1997;91:359-63.

20. Whybrew K, Murray M, Morley C. Diagnosing fever

by touch: observational study. BMJ. 1998;317:321-30.

21. Alves J, Correia JD. Ability of mothers to assess

the presence of fever in their children without using a thermometer.

Trop Doct. 2002;32:145-6.

22. Callanan, D. Detecting fever in young infants:

Reliability of perceived, pacifier, and temporal artery temperatures in

infants younger than 3 months of age. Pediatr Emerg Care.

2003;19:240-3.

23. Chaturvedi D, Vilhekar KY, Chaturvedi P, Bharambe

MS. Reliability of perception of fever by touch. Indian J Pediatr.

2003;70:871-3.

24. Akinbami FO, Orimadegun AE, Tongo OO, Okafor OO,

Akinyinka OO. Detection of fever in children emergency care: Comparisons

of tactile and rectal temperatures in Nigerian children. BMC Res

Notes. 2010;3:108.

25. Banco L, Veltri D. Ability of mothers to

subjectively assess the presence of fever in their children. AM J Dis

Child. 1984;138:976-8.

26. Ernst TN, Philp M. Temperature assessment by

parental palpation. AM J Dis Child. 1985;139:546-7.

27. Singhi S, Sood V. Reliability of subjective

assessment of fever by mothers. Indian Pediatr. 1990;27:811-5.

28. Ford H, Hoffman BD. How good is the hand?: What

is the value of tactile fever perception among children’s caregivers?

Pediatr Res. 2004;55S:238-9.

29. Ozuah PO. Feeling the heat: Subjective assessment

of fever by parents. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:131.

30. Al-Almaie SM. The reliability of mothers to

assess the presence of fever in their children. Saudi Med J.

1999;20:696-8.

31. Rambaud-Althaus C, Althaus F, Genton B,

D’Acremont V. Clinical features for diagnosis of pneumonia in children

younger than 5 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet

Infect Dis. 2015;15:439-50.

|

|

|

|

|