|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2017;54: 208-210 |

|

Bedside Infant Manikins

for Teaching Newborn Examination to Medical Undergraduates

|

|

*Sheila Samanta Mathai, Deepak Joshi and Mrigank

Choubey

From The Department of Pediatrics, Armed Forces

Medical College, Wanowrie PO, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Sheila Samanta Mathai,

Professor and Head of Department, Department of Pediatrics, Armed Forces

Medical College, Pune 411 040, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: February 28, 2016;

Initial review: May 19, 2016;

Accepted: October 08, 2016.

Published online: November 05, 2016.

PII:S097475591600021

|

Objective: To study whether

using infant manikins during clinical posting could help in teaching

newborn examination to undergraduate medical students. Methods:

111 final MBBS students were taught newborn examination either by the

new method which included practice on infant manikins at the bedside

before examining babies (Group 1) or by the traditional method which

involved directly examining babies (Group 2). They were tested the next

day by validated OSCE stations on important aspects of the newborn

examination. Marking was done as 0 (completely incorrect), 1 (partially

correct) or 2 (completely correct). Student feedback was also taken.

Results: Scores were higher, with lesser variance, in Group

1. Student feedback was positive, favoring the new method. Conclusion:

Use of infant manikins at the bedside during clinical posting improves

the performance of undergraduate students in newborn examination.

Keywords: Competency-based medical education,

Simulation, Skill-teaching.

|

|

T

eaching large numbers of undergraduates how to

examine newborn babies in the limited time available is a challenging,

though mandatory, requirement of the undergraduate syllabus. However,

many fresh medical graduates remain diffident in actually examining

patients, specially newborns [2]. Traditional bedside demonstration of

the newborn examination by a faculty followed by supervision of students

while they examine babies themselves is tedious, and it is not always

possible to ensure that every student actually achieves the requisite

skills. We attempted to improve the traditional teaching method of

newborn examination by using an infant manikin. This study was

undertaken to determine if the use of manikin during clinics could

improve the teaching of newborn examination to undergraduate medical

students.

Methods

This was a prospective, observational study conducted

with final year MBBS students during their Pediatric rotation. After

taking the Institutional Ethics Committee clearance and informed consent

of the students, batches of students were designated as Group 1 or Test

Group (these students were exposed to the new method of teaching) and

Group 2 or Control Group (these students were subjected to the

traditional method of teaching) by draw of lots.

From a pilot study, it was calculated that a sample

size of 90 would be required to detect a 30% improvement in OSCE scores

in newborn examination in the Test group with an alpha error of 5% and

power of 80%. A convenience sample of 111 was taken to include all

medical students coming for their Pediatric posting in the final year.

53 students were assigned to the test group (2 batches) and 58 students

to the control group (2 batches) by draw of lots.

Group 1 was taught the newborn examination by the new

method wherein a faculty member first demonstrated signs on the baby

following which every student practiced on an infant manikin at the

bedside under supervision (with correction if necessary) before

examining babies themselves, in small groups, under supervision. Group 2

was taught by the traditional method wherein students observed faculty

demonstrating signs on the baby and they then performed the examination

on babies themselves, in groups, under supervision. Time allotted for

the teaching sessions was similar for both groups. Neonatal

resuscitation manikins (ResusciAnne by Laedral) were used for the study.

Students were tested by validated OSCE stations the

day after the teaching session. Assessment was done on important aspects

of the newborn examination requiring some maneuverability of the baby.

Station A consisted of aspects of the general examination (Feeling the

anterior fontanel, looking for jaundice on palms and soles, checking for

ear recoil, breast nodule and sole creases) and Station B consisted of

some aspects of the neurological examination (assessing muscle tone by

scarf sign, arm recoil, heel to ear and popliteal angle and eliciting

the neonatal reflexes namely palmar and plantar grasp reflexes and

Moro’s reflex). Adequate numbers of healthy neonates were available at

each OSCE station to ensure that no baby was examined by more than four

students, to avoid fatigue of the neonates. Consent of the mothers was

taken for the examination of the neonates. Complete asepsis and other

relevant precautions were observed during the conduct of the OSCE.

Marking was done by trained faculty on a nominal scale of 0 (completely

incorrect), 1 (partially correct) or 2 (completely correct). What

constituted 0, 1 and 2 was pre-determined and the scoring guide or

checklist was kept with the trained examiner during the session. Each

station was for 5 minutes. No student could see how others were

doing during the examination as the stations were in adjacent but

different rooms.

Scores were compared between groups using Moods

Median Test and variability in scores was compared by Levene Test. After

the study was over, students (Test group) were asked to give a feedback

on a Likert-scale on a validated questionnaire. After the end of the

study, Control group students were also given an opportunity to practice

on the infant manikins before the final examination.

Results

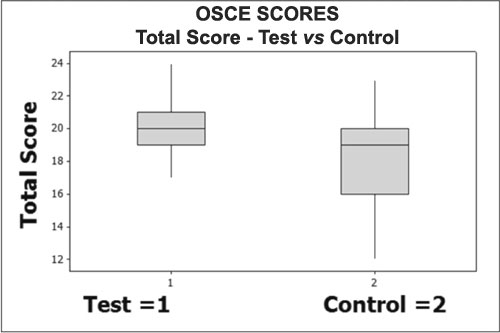

OSCE scores were statistically better in Group 1

(Test) as compared to Group 2 (Control), both in the general examination

and neurological examination stations. In addition, the variance in the

scores was significantly less in Group 1 (Fig. 1). In the

student feedback, majority felt that practice on the manikin had helped

them in performing specific aspects of the newborn examination at the

OSCE stations (Table I).

|

|

Fig. 1 Box-plot chart showing

difference in OSCE scores between group taught with a manikin

(Test group) versus group taught by traditional method (Control

Group).

|

TABLE I Feedback of Medical Undergraduates Regarding Practice in a Manikin (N=53)

|

Helped me in |

Agree (%) |

Not sure (%) |

Disagree (%) |

|

examining for |

|

|

|

|

Ear recoil |

63 |

6 |

31 |

|

Breast nodule |

67 |

8 |

25 |

|

Plantar creases |

65 |

3 |

32 |

|

Palmar reflex |

58 |

10 |

32 |

|

Plantar reflex |

62 |

5 |

30 |

|

Moro’s reflex |

54 |

5 |

26 |

|

Tone of the baby |

71 |

5 |

24 |

|

Anterior fontanel |

60 |

18 |

22 |

|

Jaundice |

67 |

11 |

22 |

|

Overall |

63 |

10 |

27 |

Discussion

This observational study looked at using a simple

manikin to improve the skills of undergraduate medical students in

examining newborns. In our study the students showed significantly

better OSCE scores when manikins were used during teaching, in addition

to the majority agreeing to the benefit of the training.

The main limitation of our study was that only one

assessment was done, and that too the day after the training session.

Hence the long-term effects of this change in training methodology

cannot be commented upon. Moreover, we did not look at the mother’s

response to this method of teaching. Medical educators realize how

anxious mothers get when young medical students handle their babies and

this method of teaching could actually alleviate this anxiety.

Although there is ample evidence that simulation in

training in critical care procedures is effective [5], its use for

teaching clinical skills in neonatology has been infrequently addressed.

Nurses and paramedics still use simple, non-computerized task-trainer

manikins for teaching nursing procedures and breast feeding [6]. Bath,

et al. [7] made an attempt to improve baby ‘handling skills’ of

medical students with mechanized dolls. Most students felt that it

helped them understand better the caretaking issues related to real

babies.

There is a felt need to embrace simulation in

pediatric teaching [8]. ‘Skills laboratory’ is now a mandatory

requirement in medical colleges as per the latest MCI guidelines [9]. We

feel that this study will add to the body of evidence on the use of

manikins in undergraduate medical education, especially at the bedside

for on examination skill.

Our study suggests that the using infant manikins at

the bedside can improve skills of undergraduates in examining newborn

babies. This method may be adopted in medical colleges during pediatric

clinical postings.

Acknowledgements: GSMC Faimer Regional Centre

Mumbai for support during planning as the project was part of the first

author’s FAIMER project and Mr Ranjan Samanta, BSc (Statistics) for

statistical advice and analysis.

Contributors: SSM: conceived the study,

supervised and participated in training, conducted the OSCE and wrote

the paper; DJ: helped in training and conduct of the OSCE and also in

editing the draft of the paper; MC: helped in conduct of the OSCE and

the questionnaire, and in editing the paper. All authors approved the

final manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Additional practice on manikin at the

bedside during clinical posting improves students’ performance

in examination of the newborn.

|

References

1. Srivastava RN, Mittal SK, Paul VK, Ramji S; for

Indian Academy of Pediatrics. IAP Guidelines for Graduate Medical

Education in Pediatrics. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:605-18.

2. Supe A, Burdick WP. Challenges and issues in

medical education in India. Acad Med. 2006;81:1076-80.

3. Okuda Y, Bryson EO, Demaria S, Jacobson L,

Quinines J, Shen B, et al. The utility of simulation in medical

education: what is the evidence? Mt Sinai J Med. 2009; 76:330-43.

4. Halamek LP, Kaegi DM, Gaba DM, Sowb YA, Smith

BC, Smith BE, et al. Time for a new paradigm in pediatric medical

education: teaching neonatal resuscitation in a simulated delivery room

environment. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E45.

5. Weinberg ER, Auerbach MA, Shah NB. The use of

simulation in pediatric training and assessment. Curr Opin Pediatr.

2009;21:282-7.

6. Aebersold M, Tschannen D. Simulation in nursing

practice: the impact on patient care. Online J Issues Nurs.

2013;31;18:6.

7. Bath LE, Cunningham S, McIntosh N. Medical

students’ attitudes to caring for a young infant-can parenting a doll

influence these beliefs? Arch Dis Child. 2000; 83:521-3.

8. Kalaniti K, Compbell DM. Simulation-based medical

education – time for a pedagogical shift. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:41-5.

9. Minimum Standard Requirements for Medical Colleges. Available

from: http:// www.mciindia.org. Accessed June 15, 2016.

|

|

|

|

|