|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53:

253-255 |

|

Gastrointestinal Fistulization in Amebic

Liver Abscess

|

|

KP Srikanth, BR Thapa and Sadhna B Lal

From Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology,

Department of Gastroenterology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr KP Srikant, Senior Resident,

Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Department of

Gastroenterology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: August 05, 2015;

Initial review: October 20, 2015;

Accepted: November 28, 2015.

|

Background: Liver abscess is a common deep seated

abscess in children; amebic liver abscess is associated with more local

complications. Case characteristics: We report two preschool

children presenting with short history of pain, fever and right upper

quadrant pain. The abscess communicated with gastro-intestinal tract

(ascending colon in case 1 and duodenum in case 2), and diagnosis of

amebic liver abscess was confirmed by DNA PCR. Outcome: Both

children were successfully managed with intravenous antibiotics and

catheter drainage. Message: Gastrointestinal fistulization may be

rarely seen in amebic liver abscess. Conservative management with

antibiotics, catheter drainage and supportive care may suffice.

Keywords: Complication, E.histolytica, Hepatic abscess.

|

|

Pyogenic liver abscess accounts for nearly 80% of

all liver abscesses in children; amebic etiology may be frequently

encountered in children from tropical developing nations [1,2]. Amebic

liver abscess is uncommon in children, but it poses higher risk of local

complications, and often proves to be a challenge in management. We

report two preschool children with fistulizing amebic liver abscess, who

were managed conservatively.

Case Reports

Case 1: A 3-year-old girl, presented

with intermittent high grade fever with chills for 2 days, which

subsided with antipyretics. Subsequently she developed periumbical pain,

which shifted to right upper abdomen. There was no abdominal distension,

vomiting or diarrhea. A transabdominal sonography (USG) on day 7 of

illness revealed an abscess in right lobe (Segment V), after which she

was referred to our center for management. On admission, child was

hemodynamically stable, and had mild pallor. Abdominal examination

revealed tender hepatomegaly. There was no free fluid or any sign of

peritonitis. Systemic examination was normal. Repeat USG revealed

abscess in the right lobe of the liver measuring 3.5 × 2.8 cm with

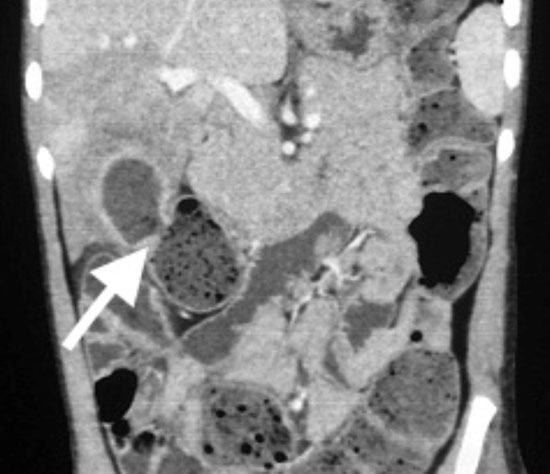

probable communication with ascending colon. Contrast enhanced computed

tomography (CECT) of abdomen showed air fluid level in the abscess and

communication with colon (Fig. 1). Blood investigations

revealed anemia (Hb 8.1 g/dL), thromobocytosis (Platelet count

650,000/µL), microcytic hypochromic anemia and hypoalbuminemia (serum

albumin 2.7 g/dL). Qualitative amebic serology (RIDASCREEN, Germany) was

positive. Bacterial culture from blood and aspirates were sterile.

Aspirate from abscess revealed a positive result for amebic DNA by

polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Child was treated with metronidazole

for 14 days. USG done after 7 days revealed decrease in size of the

abscess with disappearance of air fluid level. Child clinically improved

and was discharged from the hospital after 10 days of stay. After 3

months, USG showed complete disappearance of cavity and the

communication.

|

|

Fig.1 Coronal CECT abdomen showing

abscess communicating with the ascending colon.

|

Case 2: A 2-year-old girl, presented with

high grade intermittent fever for 7 days, watery diarrhea for initial

four days, along with pain and fullness in the right upper abdomen.

Child was evaluated at another hospital, where she was diagnosed to have

abscess in the segment VI and VII of the liver (Fig. 2a),

that was communicating with second part of the duodenum. At admission to

our center, she was hemodynamically stable, and had severe wasting

(weight for length <-3 SD) and mild pallor. Abdominal examination

revealed mild hepatomegaly; there were no local signs. She received

intravenous ceftriaxone, cloxacillin and metronidazole. Pigtail catheter

was inserted under USG guidance. The pus culture revealed growth of

E.coli, sensitive to amikacin and imipenem, and antibiotics were

changed as per the sensitivity. Aspirate was also positive for amebic

DNA PCR. Blood investigations revealed microscopic hypochromic anemia (Hb

7.4 g/dL), thromobocytosis (platelet counts 744,000/µL), and

hypoalbuminemia (S. albumin 2.2 g/dL). Amebic serology was also

positive. After initial stabilization, she was started on liquid diet,

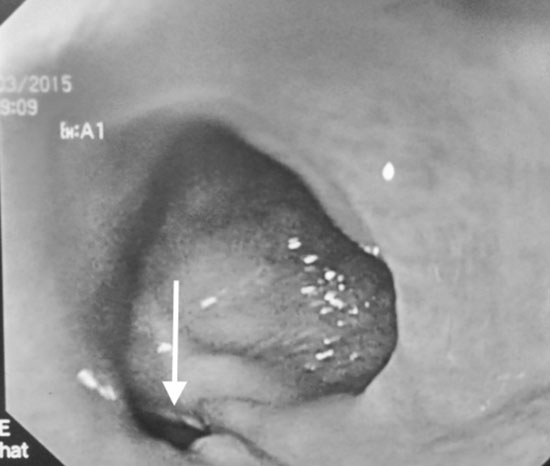

but most of the feed drained through the inserted catheter. Duodenoscopy

showed an opening at junction of first and second part of the duodenum (Fig.

2b). For next 48 hours, she was managed on intravenous fluids. Oral

feeds were started gradually, and patient tolerated well, probably due

to spontaneous closure of fistulous tract. She was discharged after

one-week stay. Intravenous antibiotics were continued for 2 weeks,

followed by oral antibiotics for a total of 4 weeks.

|

| (a) |

(b) |

|

Fig. 2 Coronal CECT abdomen showing

large abscess communicating with second part of duodenum (a);

Duodenoscopy showing opening at the junction of the D1 and D2

(b).

|

Stool microscopy was normal. The acquired and

preliminary primary immune deficiency work up like Nitroblue tetrozolum

test, immunoglobulin levels and flow cytometry for T and B cell

fractions were within normal reference range in both the patients.

Discussion

In liver abscess caused by Entamoeba histiolytica,

various virulence factors like cystinease, amebapore and Gal/GalNAc

lectin binding protein cause tissue invasion and lead to local

perforating complications [1]. Clinical distinction between amebic and

pyogenic liver abscess is at times challenging and warrants empirical

dual therapy. Amebic serology is nearly 95% sensitive and specific, but

in areas of high prevalence false positivity is a problem. DNA PCR from

the aspirate is nearly 100% sensitive and specific, but lacks widespread

availability [3]. Antigen detection from abscess aspirates hold similar

sensitivity and specificity. Size larger than 50 mm, location in left

lobe, liver failure or severe sepsis, warrants immediate drainage;

continuous catheter drainage is better than single time aspiration [4].

Metronidazole for 10 days is optimum for treatment of amebic liver

abscess [2]. Amebic liver abscess is more likely to be associated with

local complications like bronchopleural, pericardial, peritoneal and

even subcutaneous fistulizations [5]. Hepatico-gastrointestinal lumen

perforations are very rare in children; only a few cases are reported

[6]. Various treatment modalities are suggested, including major

surgeries [7]. Ideal approach would be to individualize the therapeutic

options depending upon the physiological status of the patient and

expertise of treating center.

To summarize, amebic liver abscess causing

gastrointestinal fistulization is rare in children posing diagnostic and

therapeutic challenges. Careful clinical and radiological monitoring,

and conservative management can be effective.

Contributors: SKP: prepared the manuscript and

helped in managing the cases; TBR and SBL: managed the cases and

finalized the manuscript.

Funding: None;

Competing interest: None stated.

References

1. Mishra K, Basu S, Roychoudhury S, Kumar P. Liver

abscess in children: an overview. World J Pediatr. 2010;6:210-6.

2. Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA,

Jr. Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1565-73.

3. Tanyuksel M, Petri WA, Jr. Laboratory diagnosis of

amebiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:713-29.

4. Singh S, Chaudhary P, Saxena N, Khandelwal S,

Poddar DD, Biswal UC. Treatment of liver abscess: Prospective randomized

comparison of catheter drainage and needle aspiration. Ann Gastroenterol.

2013;26:332-9.

5. Meng XY, Wu JX. Perforated amoebic liver abscess:

Clinical analysis of 110 cases. South Med J. 1994;87: 985-90.

6. Angel C, Chand N, Sankar A, Rowen J, Murillo C.

Gastric wall erosion by an amoebic liver abscess in a 3-year-old girl.

Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:429-30.

7. Singh M, Kumar L, Kumar L, Prashanth U, Gupta A, Rao ASN.

Hepatogastric fistula following amoebic liver abscess: An extremely rare

and difficult situation. OA Case Reports. 2013;2:38.

|

|

|

|

|