|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2015;52: 212 -216 |

|

Diagnostic Accuracy of Indian Scale for

Assessment of Autism (ISAA) in

Children Aged 2-9 Years

|

|

Sharmila Banerjee Mukherjee, Manoj Kumar Malhotra,

Satinder Aneja,

*Satabdi Chakraborty and #Smita

Deshpande

From Department of Pediatrics, LHMC and Associated

Hospitals, New Delhi; *Department of Psychiatry, Pt. BD Sharma PGIMS,

Rohtak, Haryana; and #Department of Psychiatry, PGIMER – Dr. Ram Manohar

Lohia Hospital, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Sharmila B Mukherjee,

Department of Pediatrics, Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital, Bangla

Sahib Road, New Delhi 110 001, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: July 07, 2014;

Initial review: September 01, 2014;

Accepted: January 09, 2015.

|

Objective: To determine the diagnostic

accuracy of Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA) in children

aged 2-9 year at high risk of autism, and to ascertain the level of

agreement with Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS).

Design: Diagnostic Accuracy study

Setting: Tertiary-level hospital.

Participants: Children aged

between 2 and 9 year and considered to be at a high risk for autism

(delayed development, and age-inappropriate cognition, speech, social

interaction, behavior or play) were recruited. Those with diagnosed

Hearing impairment, Cerebral palsy, Attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder or Pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) were excluded.

Methods: Eligible children

underwent a comprehensive assessment by an expert. The study group

comprising of PDD, Global developmental delay (GDD) or Intellectual

disability was administered ISAA by an investigator after one week. Both

evaluators were blinded. ISAA results were compared to the Expert’s

diagnosis and CARS scores.

Results: Out of 102 eligible

children, 90 formed the study group (63 males, mean age 4.5y). ISAA had

a sensitivity 93.3, specificity of 97.4, positive and negative

likelihood ratios 85.7 and 98.7 and positive and negative predictive

values of 35.5 and 0.08, respectively. Reliability was good and validity

sub-optimal (r low, in 4/6 domains). The optimal threshold point

demarcating Autism from ‘No autism’ according to Receiver Operating

Characteristic curve was ISAA score of 70. Level of agreement with CARS

measured by Kappa coefficient was low (0.14).

Conclusions: The role of ISAA in

3-9 year old children at high risk for Autism is limited to identifying

and certifying Autism at ISAA score of 70. It requires re-examination in

2-3 year olds.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder,

Certification, Diagnosis, Pervasive Developmental disorders.

|

|

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is the most recent

nomenclature for developmental disorders characterized by persistently

impaired social interaction and communication, with stereotypic behavior

[1]. These have previously been also referred to as Pervasive

developmental disorders (PDD) or Autism [2]. Western literature reports

the prevalence of PDD in children as 0.67-1.2% [3,4]. According to a

multicentric Indian community study, it is 0.8 - 1.3% in 2- to

9-year-old children [5]. Early identification of Autism is invaluable as

timely intervention is known to improve outcomes [6]. Current standard

protocols of evaluation recommend satisfying diagnostic criteria of

International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), followed by qualitative

assessment with internationally validated instruments [1,2,7,8]. These

include Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generalized (ADOS-G),

Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), and Childhood Autism Rating

Scale (CARS) [9-11]. Following this protocol is challenging in India as

differences between Eastern and Western expectations of behavior

influence parental appreciation of symptoms, leading to cultural bias

and affecting instrument psychometric properties [12]. CARS, which also

rates severity, is the only tool validated in the Indian population

[13]. ADOS-G and ADI-R use is additionally limited by cost, and

mandatory international accreditation.

An ideal Indian diagnostic tool for Autism requires

accounting for variable literacy levels and heterogeneous culture and

languages. It needs to be inexpensive, accurate, valid, reliable and

easy to administer. It should also be able to fulfill multiple purposes;

clinical (diagnosis, grading severity, planning intervention and

monitoring), research and certification. The Indian Scale for Assessment

of Autism (ISAA) was jointly developed by the National Trust, Ministry

of Health and Family Welfare, and Ministry of Social Justice and

Empowerment of the Government of India [14]. Its envisioned purpose was

to establish diagnosis, and to rate severity (that was converted to

extent of disability), so that it enabled certification and availing of

benefits from ‘Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental

Retardation and Multiple Disabilities Act’ [15].

ISAA was validated in a multi-centric study involving

1124 participants aged 3-22 year with already diagnosed PDD,

Intellectual Disability (ID), other disabilities, and normal intellect,

who belonged predominantly to higher socio-economic strata with higher

literacy levels [16]. Since manifestations are affected by effect of

intervention, developmental age and chronological age, its ability to

diagnose children, especially younger ones was questioned due to their

underrepresentation. The present study was done to determine the

diagnostic accuracy of ISAA in children aged 2-9 year, and measure the

level of agreement with CARS.

Methods

This hospital-based study was conducted in the

Pediatric Developmental Centre of a Medical College in Northern India

from December 2011 to March 2013, after obtaining institutional Ethical

Committee approval. Children between 2-9 years considered to be at high

risk for Autism were consecutively recruited. These included children

with parental concern regarding any one or more of the following:

developmental delay, age-inappropriate cognition, speech delay and

inappropriate social interaction, behavior or play. The sample size

calculated was 85, assuming sensitivity, specificity and power of 80%

each, alpha error 0.05, precision ±10% at 95% confidence interval and

attrition 10% (software-N Master 2.0, CMC Vellore). Those without

accompanying primary care giver, isolated hearing impairment, Cerebral

palsy, or already diagnosed PDD or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity

Disorder (ADHD) were excluded. Informed consent was obtained from all

eligible children.

After evaluation by Brainstem Evoked Response

Audiometry, the evaluation for autism was scheduled on two days, one

week apart. Comprehensive assessment (reference standard) was done on

the first day by a Pediatric consultant (with

³8 years experience

in developmental pediatrics). This comprised of a parental interview

with observation and examination of the child. Developmental Profile

(DP-II) was administered to estimate Developmental quotient (DQ) and

derived Intelligence quotient (IQ), and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale

(VABS II) for adaptive function and maladaptive behavior indices

[17,18]. DSM IV diagnostic criteria for PDD were applied, and CARS (DSM

III-based) for assessing severity (total scores of <30, 30-37 and >37

indicate No autism, Mild to moderate autism and Severe autism,

respectively) [2,11]. The study population was consecutively selected

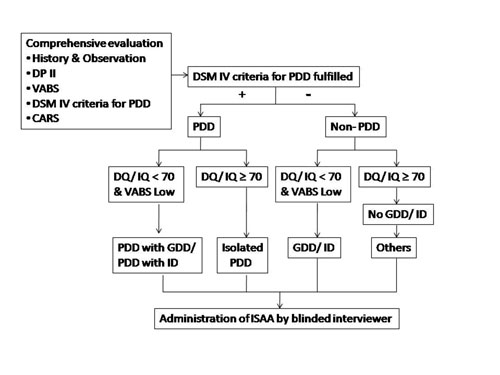

based on a standard diagnostic algorithm (Fig. 1).

Children were categorized as (i) Global Developmental Delay

(GDD)- younger than 5 years with DQ <70, not fulfilling DSM IV criteria

for PDD (ii) Intellectual Disability (ID) with IQ <70 and Low

adaptive levels (³2

SD of norms), not fulfilling DSM IV criteria for PDD (iii) PDD –

fulfilling DSM IV criteria for PDD with or without GDD/ ID and (iv)

Others- other diagnoses.

|

|

Fig. 1 Algorithm depicting evaluation

and characterization of study subjects.

|

On the next visit, ISAA (test instrument) was

administered by a trained pediatric resident. Test-retest (within 3

months) and inter-rater reliability (by an ISAA expert) was determined

in 10% and 33.3% patients, respectively. ISAA comprises of 40 items

covering 6 domains; Social relationship and reciprocity, Emotional

responsiveness, Speech-language and communication, Behavior patterns,

Sensory aspects and Cognitive. Individual items are scored on a Likert

scale based on history and interviewer observation. Autism is diagnosed

when the total score is ³170.

Severity is categorized as mild, moderate and severe Autism based on

scores of 70-108, 109-153 and >153, respectively. Both evaluators were

blinded to the results of the other’s evaluation. Counseling and further

management was done based on the expert’s diagnosis.

Statistical analysis: SPSS software (version

19.0) was used. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative

predictive values, positive and negative likelihood ratio, validity, and

reliability were measured. Kappa coefficient and Receiver Operator

Characteristic (ROC) were determined for level of agreement.

Results

The primary presenting symptoms of the 102 recruited

children were age-inappropriate behavior (64.4%), developmental or

cognitive delay (60% and 48.9%), speech delay (40%), age-inappropriate

play (32.2%) and age-inappropriate social interaction (25.5%). Five

refused participation and 7 were excluded (4 cerebral palsy, 2 neuro-degenerative

disorders and 1 hearing impairment). The study group comprised of 90

children (63 males) with mean age 4.5 years. Age-wise distribution was

2-3 years (26.7%), 3-5 years (28.9 %) and 5-9 years (44.4%). Most were

from the Middle/Lower Middle Socio-economic strata with parental

literacy till higher secondary level [19]. Expert diagnoses were PDD

(77, 85.5%), isolated GDD (3, 3.3%), isolated ID (5, 5.5%), and others

that included 1 Dravet syndrome, 2 ADHD and 2 Behavior problems (5,

5.8%). CARS scores indicated No autism in 12 (13.3%), Mild to moderate

autism in 16 (17.7%) and Severe autism in 62 (68.8%). Co-morbid GDD/ID

were observed in 87% of the children with PDD; moderate cognitive

impairment (DQ/IQ 35-50) more in children with Mild to moderate autism,

and severe cognitive impairment (DQ/IQ 20-35) more in severe autism.

ISAA administration: The average administration

time was 17.4 minutes. During administration, it became apparent that

the content of a few items were unsuitable for the younger children. On

assessment of construct validity it was noted that Pearson correlation

coefficient (r) was acceptable (0.8-0.89) in only Social and

Emotional domains with sub-optimal values ( £0.5)

in the other four. Test-retest and inter-rater reliability was 0.93-0.99

and 0.99, respectively. ISAA scores

³70 (diagnostic of autism) was seen in 76 (84.4%)

children, with rating of severity 53.9% mild, 46 % moderate, and none

with severe Autism. Psychometric parameters are presented in Table

I. Level of agreement of ISAA with CARS was low (Kappa coefficient

0.14, minimal acceptable value ³0.4);

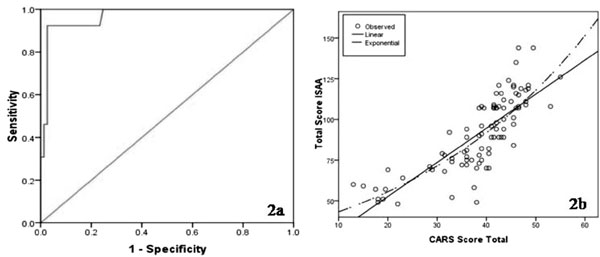

however, the ROC curve (Fig. 2a) showed the

best cut-off point at a score of 70 with 0.92 sensitivity and 0.97

specificity. The scatter diagram plotted between ISAA and CARS total

scores showed maximal clustering around ISAA scores of 70-80 (Fig.

2b).

Table 1 Psychometric Properties of Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISSA)

|

Age group |

Number |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

PPV |

NPV |

PLR |

NLR |

|

2-9 years |

90 |

92.3 |

97.4 |

85.7 |

98.7 |

35.5 |

0.08 |

|

2-3 years |

24 |

100 |

92.3 |

100 |

100 |

12.9 |

0 |

|

3-9 years |

66 |

90 |

96.4 |

81.8 |

98.2 |

25.0 |

0.11 |

|

Key: NLR- Negative Likelihood Ratio, NPV-Negative Predictive

Value, PLR-Positive Likelihood ratio, PPV- Positive Predictive

Value. |

|

|

Fig. 2 (a) ROC-curve of Indian Scale

for Assessment of Autism (ISAA) in children aged 2-9 years; (b)

Correlation between total scores obtained on ISAA and Childhood

Autism Rating Scale (CARS).

|

Discussion

This hospital-based study was conducted to determine

the diagnostic accuracy of ISAA in 2-9 year old children presenting with

features considered to be at ‘high risk’ for autism, and to ascertain

its level of agreement in rating severity with CARS. The present study

differed from the original validation study by multiple aspects: younger

participant age (study objective), smaller sample size (albeit

statistically adequate), lower socio-economic and literacy levels

(hospital patient profile), undisclosed diagnosis (eliminating

respondent bias), administration by a pediatrician, and use of

comprehensive assessment as the reference standard instead of only CARS.

This approach is considered superior to the use of a single tool, as it

qualitatively and holistically assesses the multiple facets of ASD [7].

A major limitation realized post-hoc was failure to incorporate

age-stratification and purposive sampling during patient selection. This

resulted in skewed participant profile; lesser 2-3 year olds and

children with isolated GDD/ ID.

Most children (87%) with Autism were low functioning

(co-existent GDD/ID), which is higher than international data (40-80%)

but close to a previous Indian study (90%) [20]. Reasons for this may be

explained by the aforementioned drawbacks of using International

psychometric tools in Indian children, i.e. cultural bias and

non-validation. The use of tools designed for children with GDD/ID to

assess DQ/IQ results in variable data when applied in ASD, scoring is

based on the ability to perform, without considering unwillingness

(frequently seen in autism). Adaptive function is a better reflector of

ability as it considers frequency and quality of performance [21].

Evaluation of diagnostic accuracy of a tool entails critical examination

of validity (the extent to which a test measures what it is supposed to

measure), accuracy (psychometric properties) and reliability (the degree

to which a test consistently measures whatever it measures) [22,23].

Some items demonstrated over-lapping content, ambiguous phrasing (i.e.

‘unable to grasp pragmatics of communication’), and scoring of features

considered developmentally normal in young children as deviant (i.e.

‘unable to maintain peer relationships’, ‘inconsistent attention and

concentration’). Manifestations of ASD are age-dependent; positive

symptoms (overt behaviors) are easily identified irrespective of age,

and negative symptoms (absence of pro-social symptoms) more often missed

in younger children due to non-recognition. Both require inclusion when

a single tool is used for a wide age range. The sub-optimal construct

validity of ISAA may be due to these shortcomings.

The original sensitivity and specificity of ISAA was

reported as 94.3 and 92, respectively [16]. In this study accuracy of

ISAA was found acceptable, albeit specificity was marginally lower.

Although figuratively acceptable, these parameters need to be

interpreted with caution in 2-3 year olds due to aforementioned item

unsuitability and smaller sample size. ROC curves are used to assess

inherent validity. An area-under-the-curve (AUC) value approaching 1

indicates superior performance. Despite the aforementioned fallacies,

the optimal threshold (point of maximum correct classification) was

still 70 (the point that demarcated ‘No autism’ from ‘autism’ in the

validation study). This implies that this ability remains consistent

even in 2-9 year olds. Further categorization of severity was found

unsatisfactory, evident by poor agreement with CARS and absence of

clustering around ISAA scores of >153, which had been expected since

most children had severe autism. The accuracy of ISAA is comparable to

the INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for ASD (INDT-ASD), another validated Indian

instrument designed to identify ASD without grading severity or

disability [24]. Whether INDT-ASD also displays similar drawbacks when

used in pre-school children is uncertain as an age-wise data comparison

is unavailable [24,25].

To conclude, despite its many advantages (indigenous,

free, availability in regional languages and requiring minimal training)

and acceptable psychometric properties, the role of ISAA in 3-9 year old

children is limited to only identifying autism and certifying disability

of at least 40%. This requires further examination in 2-3 year olds. It

may not be possible to use ISAA for assessing severity.

Contributors: SBM, SA: conceived the concept of

the study, and were the neuro-developmental experts of the study; they

will stand as guarantors; SBM: designed the study, and acquired clinical

data related to comprehensive assessment of study subjects; MKM:

collected ISAA related data of study subjects; SD, SC: trained MKM in

administration of ISAA; SC: also helped in collection of ISAA related

data; SBM, MKM: did the literature search and drafted the manuscript

with important inputs from SA, SD and SC. All authors approved the final

manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing Interest: None

stated.

|

What Is Already Known?

•

ISAA is reported to be an

accurate, valid and reliable Indian tool for diagnosing Autism

and grading severity and disability among persons aged 3-22

year.

What This Study Adds?

•

ISAA is psychometrically acceptable and reliable but has

sub-optimal validity in 3-9 year-old children.

•

ISAA can identify autism at a cut-off score of

³70

and thus certify disability of

³40%

in 3-9 year-old children.

|

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Autistic

Spectrum Disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric

Association; 2013.p.50-9.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Autistic

Disorder. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders. 4rth ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association;

1994.p.70-5.

3. Centers for Disease Control. Prevalence of autism

spectrum disorders-autism and developmental disabilities monitoring

network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep.

2007;56:1-28.

4. Raviola G, Gosselin GJ, Walter HJ, DeMaso DR.

Pervasive Developmental Disorders and Childhood Psychosis. In:

Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Gene III JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE, editors.

Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders,

Elsevier; 2012.p.100-7.

5. Deshmukh VB, Mohapatra A, Gulati S, Nair M,

Bhutani VK, Silberberg DH, et al. Prevalence of neuro-developmental

disorders in India. Proceedings of International Meeting for Autism

Research; 2013 May 4; Kursaal Centre, Donostia, San Sebastián, Spain.

Available from: https//imfar.confex/imfar/2013/webprogram.

Accessed April 5, 2014.

6. Chawarska K, Volkmar FR. Autism in Infancy and

Early Childhood. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D,

editors. Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. 3rd

ed. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2005.p.223-46.

7. Klin A, Saulnier C, Tsatanis K, Volknar FR.

Clinical Evaluation in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Psychological

Assessment with a Transdisciplinary Framework. In: Volkmar FR,

Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of Autism and Pervasive

Developmental Disorders. 3rd ed. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc;

2005.p.772-98.

8. World Health Organization. The International

Classification of Diseases 10. Classification of Mental and Behavioral

Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva:

World Health Organization;1992.

9. Lord C, Risi S, Cook EH, Dilavore PC. The Autism

Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic: a standard measure of social

and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J

Autism Dev Dis. 2000;24:659-85.

10. Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A. The Autism

Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic

interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive

developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Dis. 1994;24:659-85.

11. Schopler E, Reichler RJ, Renner BR. The Childhood

Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services,

Inc;1988.

12. Freeth M, Sheppard E, Ramachandran R, Milne E. A

cross-cultural comparison of autistic traits in the UK, India and

Malaysia. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43:2569-83.

13. Russell PSS, Daniel A, Russell S, Mammen P, Abel

JS, Raj LE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy, reliability and validity

of Childhood Autism Rating Scale in India. World J Pediatr 2010;6:141-7.

14. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.

Scientific Report on Research Project for Development of Indian Scale

for Assessment of Autism. New Delhi: Government of India; 2009.

15. Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. The

National Trust for Welfare of Persons with Autism, Cerebral Palsy,

Mental Retardation and Multiple Disability, The National Trust

Regulations, 2001. Available from: www.social

justice.nic.in/ntregu2001.php. Accessed June 23, 2014.

16. National Trust Web based Intervention Resource

Centre. Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism. Available from:

www.nationaltrust.co.in. Accessed May 6, 2012.

17. Alpern GD, Boll TJ, Shearer M. Developmental

Profile II. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1989.

18. Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. Vineland

Adaptive Behavior Scales. Circles Pines: AGS Publishing; 2005.

19. Kumar R, Dudala SR, Rao AR. Kuppuswamy’s

socio-economic status scale- a revision of economic parameter for 2012.

IJRDH 2013;1:2-4.

20. Juneja M, Mukherjee SB, Sharma S. A descriptive

hospital based study of children with autism. Indian Pediatr.

2005;42:453-8.

21. Sugar M, Konstantareas M, Rampton G. The adaptive

profiles of individuals with Autism spectrum disorders. J Dev Dis.

2010;16:72-6.

22. Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper: papers that

report diagnostic or screening tests. BMJ. 1997;315:540-3.

23. STARD Steering Committee. Standards for the

Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies Statement. Available from:

www.stard-statement.org. Accessed August 3, 2012.

24. Juneja M, Mishra D, Russell P, Gulati S, Deshmukh

V, Tudu P, et al. INCLEN diagnostic tool for Autism Spectrum

Disorder (INDT-ASD): Development and validation. Indian Pediatr.

2014;51:359-65.

25. Wong CM, Singhal S. INDT-ASD: An autism diagnosis tool for Indian

children. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:355-6.

|

|

|

|

|