|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51: 225 -226 |

|

Disseminated Cryptococcosis

|

|

Meenakshi Bothra, Prakash Selvaperumal, Madhulika

Kabra and *Prashant Joshi

From the Departments of Pediatrics and *Pathology,

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Madhulika Kabra, Additional

Professor, Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute of Medical

Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: January 18, 2013;

Initial review; February 11, 2013;

Accepted; January 08, 2014.

|

|

Background: Fungal infections, especially in immunocompetent

children are uncommon causes of fever of unknown origin. Case

characteristics: A 5-year-old boy with prolonged fever and no

evidence of immunosuppression. Observation: Ultrasound-guided

retroperitoneal lymph node biopsy showed granulomas and intracytoplamic

fungal yeasts; staining charactristics were suggestive of cryptococci.

Clinical and radiological improvement was seen after treatment with

amphoterecin-B. Outcome: Disseminated fungal infection should be

suspected as a cause of pyrexia of unknown origin after ruling out the

commoner causes. Biopsy from enlarged lymph node or organomegaly may

yield the diagnosis when non-invasive tests fail.

Keywords: Cryptococcal infection, Fever of

unknown origin, Immunocompetent.

|

|

Pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO) is mostly due to

an infection, especially in developing countries [1]. We report

disseminated cryptococcosis in a 5-year-old immuno-competent child.

Case Report

A 5-year-old boy was admitted with complaints of

continuous high grade fever for one month along with abdominal

distension, fast breathing and constipation. There was history of

occasional blood in stools and recurrent oral ulcers. There was no

significant past history. On examination, child was conscious and

oriented, febrile with pulse rate of 108/min and respiratory rate of

35/min. There was no pallor, icterus, cyanosis, clubbing, edema,

wasting, stunting or any evidence of micronutrient deficiency. The

abdomen was soft on palpation with a firm, non-tender hepatomegaly

(liver span 13 cm) but no splenomegaly. The examination of chest,

cardiovascular system and central nervous system was normal.

Peripheral smear examination revealed leukocytosis

(Total leukocyte count, 50.2 ◊ 10 3/L)

with eosinophilia (66% eosinophils, 18% neutrophils, 15% lymphocytes and

1% monocytes) without anemia or thrombo-cytopenia. Mantoux test, X-ray

chest and gastric aspirates for Acid-fast bacilli were negative. Bone

marrow examination revealed increase in eosinophils and its precursors

but no abnormal cells. Serum RK-39 antibody detection test and aldehyde

test were negative. Blood culture was sterile. Contrast enhanced

computed tomography (CT) of chest and abdomen showed small focal areas

of consolidation and patchy ground glass opacities in posterior basal

segments of lower lobes, along with multiple centrilobular and

peribronchial tiny nodules in both lungs suggestive of infective

etiology. Enlarged, homogenous, hypodense lymphnodes in pretracheal,

subcarinal, hilar and axillary regions, largest measuring 1.5 cm and

periportal, peripancreatic and retroperitoneal region, largest measuring

3 cm were also reported. In view of lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly and

pulmonary nodules on CT, differential diagnoses of disseminated fungal

or mycobacterial infections, metastasis, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis were

considered. Work up for the cell mediated, humoral and phagocytic

immunity did not show any evidence of an underlying immunodeficiency.

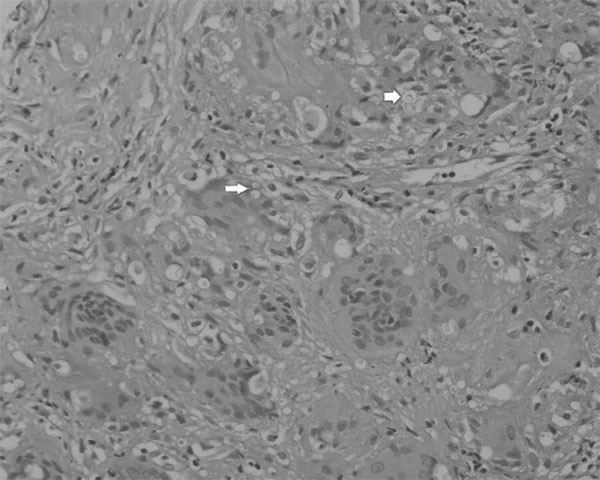

Ultrasound guided retroperitoneal lymph node biopsy showed granulomatous

inflammation with multinucleated giant cells and intracytoplasmic yeast

forms with narrow based budding (Fig. 1). Alcian

blue-periodic acid schiff (PAS) and mucicarmine stained the capsule of

the organisms, morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus. A

definite species categorization could not be done in absence of culture.

Serum and CSF cryptococcal titers were negative.

|

|

Fig. 1 Hematoxylin and eosin stained

tissue showing multinucleated giant cells with intracytoplasmic

yeast forms with narrow based budding.

|

The child was initially started on broad spectrum

intravenous antibiotics and was given albendazole in view of

eosinophilia. After lymph node biopsy report, he was started on

intravenous amphotericin B (1 mg/kg/d) which was continued for 6 weeks.

The child passed multiple round worms in stool and gradually, the

leukocytosis and eosinophilia also settled. Ultrasono-graphy of abdomen

done at the end of 6 weeks showed some reduction in the size of

retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Child was discharged on 6 mg/kg/d of oral

fluconazole with a plan to continue it for 8 weeks, and then to reassess

the size of lymph nodes on CT abdomen [2]. On follow up, the size of

retroperitoneal lymph nodes decreased further and the child remained

afebrile and asymptomatic.

Discussion

Disseminated cryptococcosis is a systemic fungal

infection generally seen in immunocompromised individuals. Recently,

there have been reports of cryptococcosis in immunocompetent patients

[3]. It usually presents with respiratory tract, central nervous system

and skin involvement. Hepatic, lymph node and bone marrow involvement in

immunocompetent people has been occasionally reported [4,5].

Cryptococcal infection is difficult to diagnose because of the

non-specific signs and symptoms, the insidiousness of the course and the

coexistence with other diseases [3]. The report of retroperitoneal lymph

node biopsy helped us clinch the diagnosis of disseminated

cryptococcosis, after commoner causes like disseminated tuberculosis and

lymphoreticular malignancy were ruled out. Diagnosis of cryptococcal

infection depends upon demonstration of growth of organisms on

Saboraudís media with characteristic biochemical reactions (urease,

phenyloxidase) or demonstration of encapsulated yeast like organisms on

India ink or PAS staining followed by positive mucicarmine or Masson

Fontana staining. Demonstration of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide

antigen in titers more than 1:8 in serum or CSF is also diagnostic [4].

Amphotericin B (0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/d, intravenously)

plus flucytosine (100 mg/kg/d, orally, in four divided doses) is

recommended for at least four weeks for initial therapy [6].

Consolidation therapy should then be initiated with fluconazole (6

mg/kg/d) for eight weeks, and 3 mg/kg/d for six to twelve months [2].

We conclude that systemic fungal infections including

disseminated Cryptococcosis is possible even in immunocompetent children

and should be considered as cause of PUO after commoner causes have been

ruled out.

Contributors: MB: compiled clinical details and

investigations and drafted the manuscript; PS: work up of the patient

and drafting the manuscript; MK: supervised the management of child and

revised the manuscript and PJ: pathological diagnosis and drafting the

manuscript.

Funding: none; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. Kejariwal D, Sarkar N, Chakraborti SK, Agarwal

V, Roy S. Pyrexia of unknown origin: a prospective study of 100 cases. J

Postgrad Med. 2001;47:104-7.

2. Chen SC, Playford EG, Sorrell TC. Antifungal

therapy in invasive fungal infections. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:1-9.

3. Paranada KS, Victorio-Navarra ST, Dy EE.

Disseminated cryptococcosis in two Filipino patients. Phil J Microbiol

Infect Dis. 1999;28:109-16.

4. Agarwal V, Sachdev A, Agarwal G, Mohan H, Anjali.

Disseminated cryptococcosis mimicking lymphoreticular malignancy in

a HIV negative patient. JK Science. 2004;6:93-5.

5. Lee HS, Park HB, Kim KW, Sohn MH, Kim KE, Kim MJ,

et al. A case of mediastinal and pulmonary cryptococcosis in a

3-year-old immunocompetent girl. Pediatr Allergy Respir Dis (Korea).

2011;21:350-5.

6. Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA, Pappas PG,

Perfect JR, Powderly WG, et al. Practice guidelines for the

management of cryptococcal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:710-8.

|

|

|

|

|