|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2013;50:

295-299 |

|

Locally-Prepared Ready-to-Use Therapeutic

Food for Children with Severe Acute Malnutrition:

A Controlled Trial

|

|

Govind Singh Thakur, HP Singh and Chhavi Patel

From the Department of Pediatrics, Gandhi Memorial

Hospital and SS Medical College, Rewa, MP, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Govindsingh P Thakur,

Kochar ward, Hinganghat, Wardha, Maharashtra, 442301, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: June 14, 2011;

Initial review: July 06, 2011;

Accepted: August 31, 2012.

Published online: 2012, October 05.

PII: S097475591100501

|

|

Objective: To compare the efficacy of locally-prepared ready-to-use

therapeutic food (LRUTF) and locally-prepared F100 diet in

promoting weight-gain in children with severe acute malnutrition

during rehabilitation phase in hospital.

Study design: Non-randomized

Controlled trial.

Setting: Pediatric ward of

tertiary care public hospital in Central India.

Study period: 1 October, 2009 to

30th May, 2010.

Subjects: Children aged 6 to 60

months, diagnosed as severe acute malnutrition and hospitalized during

study period.

Intervention: Random group

allocation followed for selection of intervention and control cohorts.

The control cohort enrolled during October 1, 2009 to January 31, 2010

received F100 while the intervention cohort enrolled during 1 February

to 15 May 2010 received LRUTF. Subjects receiving either of the two

therapeutic foods were temporally separated to minimize the spillover

effect. The study subjects and the technician delegated for measuring

weight was blinded for type of intervention.

Primary outcome variable: Rate of

weight-gain/kg/day.

Results: There were 49 subjects

in each group. Both groups were comparable. Rate of weight-gain was

found to be (9.59±3.39 g/kg/d) in LRUTF group and (5.41 ± 1.05 g/kg/d)

in locally prepared F100 group. Significant difference in rate of weight

gain was observed in LRUTF group (P<0.0001; 95% CI 3.17-5.19). No

serious adverse effect was observed with use of LRUTF.

Conclusion: LRUTF promotes more

rapid weight-gain when compared with F100 in patients with severe acute

malnutrition during rehabilitation phase.

Key words: Malnutrition, Management, Ready-to-use

therapeutic food, India.

|

|

Guidelines provided by World Health Organization

(WHO) for management of children with severe malnutrition advise two

formula diets, F75 and F100. F75 (75 kcal/100mL) diet is used during

initial phase of treatment while F100 (100kcal/100mL) is used during

rehabilitation phase after appetite has returned [1].These diets can be

prepared locally using cow milk, sugar, vegetable oil, and water.

These diets need to be prepared just before

consumption, as cow milk used can act as growth medium for pathogenic

bacteria if proper hygienic conditions are not maintained. Milk can be

easily adulterated. Shelf-life of locally produced F100 depends on its

constituents like milk which has a very short shelf-life of few hours in

tropical climates [2].

To deal with these problems there was a need to

develop a therapeutic feed which had prolonged shelf-life, was a poor

growth media for pathogens, could be prepared locally with available

resources, was cheap and locally acceptable. A local ready to use

therapeutic food (LRUTF) was prepared from groundnut (25%), milk powder

(30%), sugar (30%), and vegetable oil (15%) by weight. In this study,

efficacy of this LRUTF in promoting weight-gain during rehabilitation

phase was compared with locally-prepared F100 diet.

Methods

All patients aged 6 to 60 months, diagnosed as Severe

acute malnutrition hospitalized in our institution during the study

period (1 October 2009 to 30 May 2010) were included in study. The study

was non-randomized controlled trial. Patients were divided into two

groups depending on the dates of hospitalization. Study was conducted

with permission from hospital authorities.

Severe acute malnutrition was defined as the presence

of severe wasting (<70% weight-for-height or

³3SD) (WHO standards)

[3], bipedal pitting edema of nutritional origin or mid

upper arm circumference (MUAC) of <

11.5 cm in children between 6-60 months of

age [4]. Patient was labelled as uncomplicated if

he was alert, with preserved appetite i.e. appetite test passed,

clinically assessed to be well (absence of general danger signs and

severe anemia, cough and difficult/fast breathing, cold to touch and

severe dehydration), and living in a conducive home environment. All

uncomplicated patients were treated at home and others were

hospitalized.

Appetite test:

Poor appetite was one of the criteria for

hospitalization and inpatient treatment. Appetite was tested with help

of measured quantity of LRUTF (approximately 5g/kg). The idea of doing

appetite test is that, any child who passes appetite test means that he

is able to take ¼ of his maintenance calories at a time, and thus if

four or five equal amounts of feeds are given at home child will not

further lose weight. A child failing in appetite test was hospitalized

[5].

Patients were excluded from study if they refused to

get hospitalized, refused for consent, left against medical advice

before discharge or died during stabilization phase. All children below

age of 6 months with severe acute malnutrition were considered

complicated and hospitalized, but they were excluded from study.

Sample size estimation: Primer of Biostatistics

Ver. 5.0 was used for estimation of sample size based on expected means

in two groups for hypothesis testing. With 5% alpha error, 80% power,

expected difference of means as 2, and expected SD within two groups as

3.4, (calculated from the observations of Diop EHI, et al. [6] )

the minimum sample size was estimated as 47 in each groups. A sample

size of 49 was taken after adjusting for the effect of likely attrition.

Intervention: Upon patient enrolment, informed

written consent was taken from the caregiver. Information about the

history of illness, family demographics, and literacy status of

caregiver was acquired. Appetite test was done using LRUTF. Initial

stabilisation phase was begun after hospitalization, life-threatening

problems were identified and treated, specific deficiencies were

corrected, metabolic abnormalities were reversed and feeding was begun.

During this initial stabilization phase, cautious feeding was begun with

F75. This phase was similar in both cohorts. Once patient showed signs

of improvement (disappearance of fever and other signs of infection,

regaining of appetite, started losing edema) he was shifted into

rehabilitation phase.

All those children who successfully completed

stabilization phase were included in this study. On completing

stabilization phase, children were given a test feeding of the LRTUF and

locally prepared F100 to screen for food allergy and ensure

acceptability. These children were assigned into one of the two groups

by systematic allocation according to order of entry into the study,

with initial participants receiving F 100 (all subjects admitted between

October 1, 2009 to January 31, 2010 ), while children enrolled in later

part of study (between 1 February to 15 May, 2010) received locally

prepared LRUTF .

During rehabilitation phase, children received either

4 meals of F100 or 4 meals of LRUTF daily according to the group

allocation, in addition to 4 meals of food from family pot. Children in

LRUTF group received measured quantity of 12 g/kg/day of LRUTF daily.

Children in F100 group received 60 mL/ kg/day of F100 in 4 quarters.

This therapeutic food provided approximately 60 calories/kg/day.

Patients also received approximately 60 kcal/kg/day by family food.

Thus, a total of 8 feeds per day and around 120 kcal/kg/day with 1-1.5

g/kg of protein were given to every child. All children received

vitamins and mineral supplements as per WHO recommendations [1].

F100 was prepared in lots, quantity of which was

determined by number of children with severe acute malnutrition admitted

at that particular time. It was prepared at 8.00 A.M., 2.00 P.M., 8.00

P.M. and 2 A.M. by one of the investigators. Food from family pot was

consumed at 11.00 A.M., 5.00 P.M., 11.00 P.M. and 5.00A.M. under

observation of an investigator. LRUTF was prepared every Sunday in

hospital kitchen under all aseptic precautions and was stored in sterile

airtight containers of 1kg each. Measured quantity of LRUTF was given

just prior to consumption. Left over LRUTF at the end of day was

discarded and new container was opened each day. Timings of feeding with

LRUTF were similar to those of F100. If child felt hungry in between

meals he was offered family food.

Children were considered ready for discharge when

they were alert and active, eating at least 120-130 kcal/kg/day with

consistent weight gain (of at least 5 g/kg/day for 3 consecutive days)

on exclusive oral feeding, receiving adequate micronutrients, free from

infection, had completed immunization appropriate for age and had gained

at least 15% of admission weight; and the caretaker had been sensitized

to weight gain [4].

Before discharge from hospital, caregiver of each

child was taught to prepare LRUTF and locally prepared F100. They were

advised to give LRUTF and locally prepared F100 at home in same quantity

as in hospital and report every 15 days. Weight gain was calculated

before discharge and on each follow-up. Patients were followed till they

achieved weight <1 SD below mean for height. If a child had poor

weight-gain during follow-up, he was readmitted and treated as secondary

failure. Failure to respond (secondary failure) was indicated by

failure to gain at least 5 gm/kg/day for 3 consecutive days during

rehabilitation phase [1].

Outcome: Primary outcome variable was rate of

weight gain (g)/kg bodyweight/day. This was calculated as follows:

(W2 – W1) ×1000

----------------------

(W1 × N)

Where, W2 – Weight at the time of discharge (kg); W1

– Minimum weight during study period (kg); and N – Number of days from

minimum weight to discharge.

Recipe for F100 and LRUTF: Composition of LRUTF

and F-100 is described in Table I. Production of LRUTF

included grinding, mixing and packaging. Shelled peanuts were roasted in

a roaster at a temperature of approximately 160º C for 40-60 minutes.

This was followed by grinding them into smaller particle sizes in a

grinder such as a hammer mill. Skimmed milk powder, the ground peanuts,

vegetable oil, powdered sugar were then blended in a mixer. The paste

was then homogenized to further reduce particle size (< 200 µm), and

packed [7].

TABLE I Composition of F100 and Locally Prepared F100 Diet and Locally-prepared

Ready-to-use Therrapeutic Food Used in the Study

|

Ingredient |

LRUTF (1kg) |

F 100 (1L) |

|

Fresh cow’s milk |

- |

880 mL |

|

Sugar |

300 g |

75 g |

|

Vegetable oil |

150 g |

20 g |

|

Peanut butter |

250 g |

- |

|

Milk powder |

300 g |

- |

|

Water

|

Nil |

To make 1000 mL |

|

Calories

|

5440 kcal/kg |

1053.8 kcal/L |

|

Proteins

|

136.3 g/kg |

30 g/L |

|

For a child weighing 10 kg

received 120 g/day of LRUTF; i.e. 653 kcal of energy and 16.35 g

of protein. For a child weighing 10 kg received 600 mL/day of

F100; i.e. 632 kcal of energy and 18.4 g of protein.

|

Data analysis: The collected data was entered

into spread sheet programme and analyzed by statistical software Primer

of Biostatistics (Ver. 5.0). The inter-group outcome variables were

analysed by comparing mean and standard deviation in each group.

Unpaired t test was used for hypothesis testing. P<0.05

was considered significant.

Results

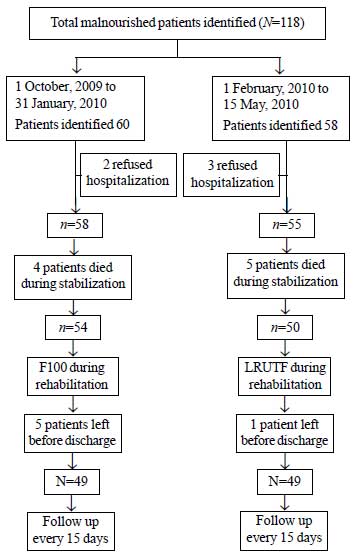

During the study period, 118 patients with severe

acute malnutrition were identified, of which 9 patients died during

initial stabilisation phase, 5 patients refused to get hospitalized and

6 patients left before treatment was completed, and were excluded from

the study (Fig. 1). 76 children were in age group of 6

months to 24 months and 22 children were in age group 25 months to 60

months. There were 49 boys (50%). Age and sex distribution in both

cohorts was comparable. 31 (31.6%) patients had edematous malnutrition.

53 (54.1%) patients passed appetite test on admission.

|

|

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

|

Table II compares the outcome variables

between the two groups. None of the patient in LRUTF group had any

complications related with LRUTF. No patient had peanut allergy.

TABLE II Outcome of Hospitalized Malnourished Children Managed With Locally-prepared

F100 and Locally-prepared Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food*

|

LRUTF Group (n=49)

|

F100 group (n=49)

|

Mean difference |

|

Weight gain, Mean (SD) |

No. |

Weight gain, Mean (SD)

|

No. |

(95 % CI) |

|

Rate of wt. Gain (g/kg/day) in study

cohort

|

9.59 (±3.39)

|

49 |

5.41 (±1.05) |

49 |

3.174-5.186 |

|

Rate of wt gain (g/kg/day) in

edematous pt |

7.94 (±2.19)

|

15 |

5.10 (±0.88)

|

16 |

1.629-4.051 |

|

Rate of wt gain (g/kg/day) in non

edematous pt |

10.32 (±3.59)

|

34 |

5.66 (±1.10)

|

33 |

3.356-5.964 |

|

Rate of wt gain (g/kg/day) in pt

with good appetite |

10.55 (±3.58) |

28 |

6.06 (±0.85) |

25 |

3.015-5.965 |

|

Rate of wt gain (g/kg/day) in pt with

poor appetite |

8.30 (±2.70) |

21 |

4.73 (±0.78) |

24 |

2.408-4.732 |

|

Rate of wt gain (g/kg/day) on follow up

(g/kg/d) |

9.43 (±2.90) |

16 |

5.22 (±0.84) |

18 |

2.756-5.664 |

|

Duration of hospital stay (days) |

13.04 (±0.16)

|

49 |

16.20 (±4.73) |

49 |

-4.502-1.818 |

|

*P<0.0001 for all measurements;

LRUTF: Locally-prepared Ready-to-Use therapeutic food.

|

Discussion

The results indicate rate of weight-gain is

significantly more with use of LRUTF than F100 during rehabilitation

phase of SAM management. Further, the rate of weight-gain after

discharge from hospital is more with use of LRUTF. Duration of

hospitalization is also significantly less with use of LRUTF. This has

great relevance in treatment of severe malnutrition at the national

level as it can decrease the cost of treatment to a great extent. LRUTF

was well tolerated in all age groups without showing any side-effects.

Major limitation of this study was that children were

not randomly assigned thereby increasing chances of selection bias.

Another limitation was that study was not blinded. There was a practical

difficulty in blinding because of different appearance of the two

therapeutic regimens; one being liquid and other being in powdered form.

Observer bias in study was reduced by the fact that primary outcome

measure of this study was determined by nude bodyweight determined on a

calibrated electronic weighing scale rather than by a more subjective

assessment. No observation was made to confirm whether mothers were

actually feeding their children the recommended amount of LRUTF or F100

rigorously at home. Although no peanut allergy was found in study, this

might not be the case in the general population. Sample size in this

study was small as this study was done as a pilot project.

Ciliberto, et al. [8] conducted a study to

test efficacy of LRUTF and standard WHO treatment (F100) in promoting

weight-gain in children with severe acute malnutrition. Their study was

done in uncomplicated SAM children and on outpatient basis [8]. The rate

of weight-gain in the study was 3.5 g/kg/day in LRUTF group and 2

g/kg/day in other group.

Present study was conducted in complicated SAM

patients who were hospitalized. A similar study in hospitalized patients

by Diop, et al. [6] reported average weight-gains of 15.6 and

10.1 g/kg/d in the RTUF and F100 groups, respectively [6]. In our study,

the average weight gain was 9.59g/kg/day and 5.41 g/kg/day. A systematic

review also suggested that use of therapeutic nutrition products like

RUTF for home-based management of uncomplicated SAM appears to be safe

and efficacious [9].

Although rate of weight-gain in studies mentioned

above was different, but in all these studies, rate of weight gain was

better in LRUTF group versus F100. With good acceptability in the

population, no adverse reactions, and better weight-gain, LRUTF is of

great help in the management of rehabilitation phase of severe acute

malnutrition. Further studies with large sample size and home-based

follow-up should be conducted to assess the feasibility and efficacy of

locally-prepared RUTF in management of SAM.

Acknowledgments: Dr RJ Meshram for

critically reviewing the article and Dr Vijay Bhagat for statistical

analysis of the data.

Contributors: GT and CP prepared and edited the

manuscript as per the journal requirements. HPS planned and supervised

the study and would be the guarantor. The final manuscript was approved

by all authors.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What Is Already Known?

• F100 promotes weight gain in rehabilitation

phase of malnutrition treatment.

What This Study Adds?

• Locally-prepared Ready-to-use Therapeutic

Food is better than F100 in promoting weight-gain in

hospitalized children with severe acute malnutrition during

hospitalization and after discharge.

|

References

1. World Health Organization. Management of Severe

Malnutrition: a Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health workers.

Geneva: WHO; 1999.

2. Brewster DR, Manary MJ, Menzies IS, Henry RL,

O’Loughlin EV.Comparison of milk and maize based diets in kwashiorkor.

Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:242–8.

3. WHO Child Growth Standards. Available from URL:

www.who.int/childgrowth/standards. Accessed on June 28, 2011.

4. WHO Child Growth Standards and the Identification

of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children, A Joint Statement

by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund.

Available fromURL:www.who.int/nutrition/publications/en/manage_ severe_

malnutrition_ eng.pdf . Accessed on June 28, 2011.

5. Mother and Child Nutrition, Mother Infant and

Young Child Nutrition & Malnutrition. Available from URL:

http://motherchildnutrition.org/malnutrition-management/info/appetite-test.html.

Accessed on June 28, 2011.

6. Diop EHI, Dossou NI, Ndour MM, Briend A, Wade S.

Comparison of the efficacy of a solid ready-to-use food and a liquid,

milk-based diet for the rehabilitation of severely malnourished

children: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78: 302-7.

7. Manary MJ. Local production and provision of

ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) spread for the treatment of severe

childhood malnutrition. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27:S83-9.

8. Ciliberto MA, Sandige H, Ndekha MJ, Ashorn P,

Briend A, Ciliberto HM, et al. Comparison of home-based therapy

with ready-to-use therapeutic food with standard therapy in the

treatment of malnourished Malawian children: a controlled, clinical

effectiveness trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:864-70.

9. Gera T. Efficacy and safety of therapeutic nutrition products for

home-based therapeutic nutrition for severe acute malnutrition: a

systematic review. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:709-18.

|

|

|