|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2013;50:

283-288 |

|

Etiology and Outcome of Crescentic

Glomerulonephritis

|

|

Aditi Sinha, Kriti Puri, Pankaj Hari, *Amit Kumar Dinda

and Arvind Bagga

From the Division of Nephrology, Department of Pediatrics, and

*Department of Pathology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New

Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Arvind Bagga, Professor, Division of

Nephrology, Department of Pediatrics, 3053, Teaching Block, All India

Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi.

Email: arvindbagga@hotmail.com

Received: June 07, 2012;

Initial review: June 26, 2012;

Accepted: August 02, 2012.

Published online: 2012, July 5.

PII: S097475591200481

|

Objective: To determine the etiology, course and predictors of

outcome in children with crescentic glomerulonephritis (GN).

Study design: Retrospective, descriptive study.

Setting: Pediatric Nephrology Clinic at a

referral center in Northern India.

Methods: Clinic records of patients aged <18 year

with crescentic GN diagnosed from 2001-2010 and followed at least

12-months were reviewed. Crescentic GN, defined as crescents in

³50%

glomeruli, was classified based on immunofluorescence findings and

serology. Risk factors for renal loss (chronic kidney disease stage 4-5)

were determined.

Results: Of 36 patients, (median age 10 yr) 17

had immune complex GN and 19 had pauci-immune crescentic GN. The

etiologies of the former were lupus nephritis (n=4),

postinfectious GN (3), and IgA nephropathy, Henoch Schonlein purpura and

membranoproliferative GN type II (2 each). Three patients with

pauci-immune GN showed antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA).

Rapidly progressive GN was present in 33 patients, and required dialysis

in 12. At median 34 (19-72) months, 2 patients with immune complex GN

and 8 with pauci-immune GN showed renal loss. Renal survival was 94.1%

at 3 yr, and 75.3% at 8 yr in immune complex GN; in pauci-immune GN

survival was 63.2% and 54.1%, respectively (P=0.054). Risk

factors for renal loss were oliguria at presentation (hazards ratio, HR

10.50; P=0.037) and need for dialysis (HR 6.33; P=0.024);

there was inverse association with proportion of normal glomeruli (HR

0.91; P=0.042).

Conclusions: Pauci-immune GN constitutes one-half

of patients with crescentic GN at this center. Patients with pauci-immune

GN, chiefly ANCA negative, show higher risk of disease progression.

Renal loss is related to severity of initial presentation and extent of

glomerular involvement.

Key words: Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, Rapidly

progressive glomerulonephritis, Vasculitis.

|

|

Crescentic glomerulonephritis (GN), characterized

by rapidly progressing renal failure, is relatively rare in childhood.

Reports are limited to case series with scant information on long-term

course [1-5]. Crescentic GN in children is commonly secondary to

postinfectious GN, Henoch Schonlein purpura and IgA nephropathy [1,3,4].

While pauci-immune crescentic GN is common in adults [6,7], there are

few reports of this condition in children [2,3].

In 1992, we described our experience on the clinical

features and renal histology in 43 consecutive patients with crescentic

GN [4]. Immunofluorescence examination showed immune complexes in 17 of

20 cases; testing for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) was

not available. Outcomes were unsatisfactory irrespective of etiology,

with progressive renal impairment in 86% cases. During the last decade

we have noticed a reduction in proportion of patients with

postinfectious GN and increasing occurrence of pauci-immune crescentic

GN. While recent reports are limited [1,8], prompt diagnosis and

intensive therapy has resulted in better patient outcomes. The present

report describes the etiological profile and clinical course among 36

patients with crescentic GN evaluated at this centre. The short-term

course in nine patients has been reported elsewhere [9].

Methods

Hospital records were reviewed to identify children

(<18 years) diagnosed with crescentic GN between June 2001 and June 2010

and followed for at least 12-months. Records were reviewed for clinical

and biochemical features, therapies received and course. Blood was

examined for levels of creatinine, electrolytes, complement C3,

antistreptolysin O and antinuclear antibodies. Prior to 2006, ANCA were

screened by immunofluorescence; later enzyme immunoassay for

myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3 were also performed [10]. Standard

definitions were used for hematuria (>5 erythrocytes/high power field of

centrifuged specimen), proteinuria (protein to creatinine ratio, Up/Uc

³0.2 mg/mg),

nephrotic syndrome (edema, proteinuria 3-4+ or Up/Uc >2.0, and serum

albumin <2.5 g/dL) [11] and hypertension (blood pressure >95th

percentile for age, gender and height) [12].

Histology: Light microscopy examination was

considered adequate in presence of at least one core with

³10 glomeruli.

Crescents were defined as proliferation of parietal cells forming two or

more cell layers in the Bowman space; crescentic GN was the presence of

crescents in 50% or more glomeruli [6]. Specimens were examined for

cellularity of crescents, sclerosis, neutro-phil infiltration, fibrinoid

or tuft necrosis, mesangial or endocapillary hypercellularity and

tubulointerstitial changes. Immunofluorescence (IF) examination was done

for pattern and intensity of staining for immuno-globulins, C3 and C1q.

Based on staining of immune deposits and serology, histology was

classified as immune-complex GN (granular deposits of immune complexes

along capillary wall and mesangium), pauci-immune GN (scant or no

deposits, with or without positive ANCA) and anti-glomerular basement

membrane GN (linear antibody deposits). Standard criteria were used for

systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Henoch Schonlein purpura and

Wegener’s granulomatosis [13,14].

Therapy

Management included maintenance of fluid and

electrolyte balance, dialysis if indicated, and therapy of coexisting

infections and hypertension.

Pauci-immune GN. Remission was induced with 3-6

pulses of IV methylprednisolone (15-20 mg/kg, maximum 1 g/day), followed

by IV cyclophosphamide (500-750 mg/m2)

for 6 doses at 3-4 week intervals, and oral prednisone (1.5 mg/kg/day

for 4 weeks, tapered to alternate-day). Patients who were dialysis

dependent also received double-volume plasma exchange for 7 days. During

the maintenance phase, patients received either azathioprine (2

mg/kg/day) or mycophenolate mofetil (500-750 mg/m2/day)

for two or more years. Additional therapies included IV immunoglobulin

and rituximab in one patient with Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Immune complex crescentic GN. Initial therapy

with IV methylprednisolone was followed by tapering doses of oral

steroids for 6 months. Patients with crescentic GN secondary to SLE, IgA

nephropathy and HSP received IV cyclophosphamide for 6 months, followed

by long-term therapy with azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil.

Patients with postinfectious GN also received oral cyclophosphamide (2

mg/kg/day) for 12 weeks.

Monitoring and Follow up: Patients were followed

every 3-6 months. Outcome at last follow up was categorized as: (i)

complete recovery (urine protein nil/trace; serum albumin >2.5 g/dL and

estimated GFR >90 mL/min/1.73 m2),

(ii) partial recovery (abnormal urinalysis: microscopic hematuria,

³1+

proteinuria; hypertension; or estimated GFR 60-90 mL/min/1.73 m2),

(iii) chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3 (GFR 30-60 mL/min/1.73

m2) and (iv) renal loss: CKD

stage 4 or 5 (GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using

STATA 11.0 (College Station, Texas). Summary statistics are presented as

median (interquartile range, IQR). Clinical features were compared using

chi square and ranksum tests; renal survival (free of renal loss) was

compared using Kaplan Meier analyses. Factors impacting outcome were

examined by Cox regression and reported as hazards ratios (HR) with 95%

confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Of 36 patients with crescentic GN, 21 were boys. The

median (IQR) age at onset of disease was 10 (8-11.5) years; 15 (41.7%)

children were younger than 10 years. The clinical and laboratory

features are presented in Table I. Based on histopathology

and IF examination, immune complex GN and pauci-immune crescentic GN

were present in 17 and 19 patients, respectively. Fifteen (88.2%)

patients with the former and 18 (94.7%) with the latter presented with

rapidly progressive GN; 3 had puffiness and mildly impaired renal

function. Six patients in each group had systemic symptoms at

presentation, including one with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Thirteen

patients with pauci-immune GN had isolated renal involvement.

TABLE I Patient Characteristics at Presentation

|

Characteristic |

Immune

|

Pauci-immune

|

P

|

|

complex |

crescentic GN

|

|

|

GN (n=17) |

(n=19) |

|

|

Boys |

11 (64.7) |

10 (52.6) |

0.46 |

|

Age, y

|

11 (10-12) |

9 (7-11) |

0.09 |

|

Duration of

|

8 (3-21) |

4 (3-16) |

0.57 |

|

symptoms, weeks |

|

Oliguria |

9 (52.9) |

12 (57.9) |

0.77 |

|

Gross hematuria |

9 (52.9) |

12 (63.2) |

0.54 |

|

Fever |

6 (35.9) |

10 (52.6) |

0.30 |

|

Seizures,

|

3 (17.7)* |

1 (5.3) |

0.24 |

|

encephalopathy |

|

Rash |

6 (35.3) |

4 (21.1) |

0.46 |

|

Arthralgia |

2 (11.8) |

2 (10.5) |

0.91 |

|

Hypertension

|

10 (58.8) |

16 (84.2) |

0.14 |

|

Creatinine, mg/dL |

1.8 (1.2-4.8) |

3.9 (1.7 - 5.3) |

0.24 |

|

Nephrotic range proteinuria |

13 (76.5) |

15 (83.3) |

0.69 |

|

Categorical variables are shown as number (percentage) and

continuous variables as median (interquartile range); *2 with

hypertensive encephalopathy; 1 with systemic lupus erythematosus. |

Histology: Adequate tissue for histopathology was

available in 35 patients; renal biopsy in one showed only 4 glomeruli, 3

of which had crescents. The median (IQR) proportion of glomeruli showing

crescents was 62% (50-89%) in patients with immune complex GN and 67%

(50-96%) in pauci-immune crescentic GN; crescents involving >80%

glomeruli were seen in 6 and 7 cases, respectively. In immune complex

GN, crescents were cellular and fibrocellular in 8 patients each (47.1%

each); one patient showed fibrous crescents. The proportion of sclerosed

and normal glomeruli was 20% (0-41%) and 14.5% (0-29%), respectively.

Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis was noted in 10 biopsies,

while 8 showed chronic inflammatory infiltrate.

Biopsies in patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN

showed cellular (n=11, 57.9%), fibrocellular (n=6, 31.6%)

or fibrous (n=2, 10.5%) crescents. The median proportion of

sclerosed and normal glomeruli was 8.5% (IQR 0-40%) and 5% (0-21%)

respectively. Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis were seen in 14

(73.7%) and 12 (63.2%) biopsies. Fibrin deposition was present in 12

(63.2%) cases and tuft necrosis in 4 biopsies. Faint deposits of C3 and

IgM were seen in 3 and 1 patients, respectively.

Immune complex GN was secondary to SLE in 4 patients,

and IgA nephropathy, Henoch Schonlein purpura and membranoproliferative

GN type II in two cases each; GN was postinfectious in 3 cases and

idiopathic in 5 patients. Three patients with pauci-immune

crescentic GN were ANCA positive. Two patients had microscopic angiitis

based on constitutional symptoms and specificity against myeloperoxidase

and one with chest infiltrates and specificity against proteinase-3 was

diagnosed as Wegener’s granulomatosis. Serology for ANCA was negative in

16 patients with pauci-immune GN.

Twelve (33.3%) patients required dialysis at

presentation. Eight patients, all with pauci-immune GN, underwent plasma

exchanges. Therapy for induction included IV methylprednisolone (n=31;

86.1%), IV cyclophosphamide (27; 75%) and oral cyclophos-phamide [4].

Maintenance immunosuppression included oral prednisolone (36; 100%),

azathioprine (18; 50%) and mycophenolate mofetil (11; 30.6%).

TABLE II Outcome at Last Follow Up

|

Immune

|

Pauci-immune

|

|

complex

|

crescentic |

|

GN (n=17) |

GN (n=19) |

|

Normal renal function and urinalysis

|

4 (23.5) |

3 (15.8) |

|

Abnormal urinalysis or hypertension |

7 (41.2) |

5 (26.3) |

|

Chronic kidney disease stage 2-3 |

4 (23.5) |

3 (15.8) |

|

Chronic kidney disease stage 4-5

|

2 (11.8) |

8 (42.1) |

The outcome at last follow up, at 34 (19-72) months,

is shown in Table II. Seven (19.4%) patients had

complete recovery, while 10 (30.6%) had CKD 4-5. The latter includes 3

patients who were followed for 53-121 months after renal

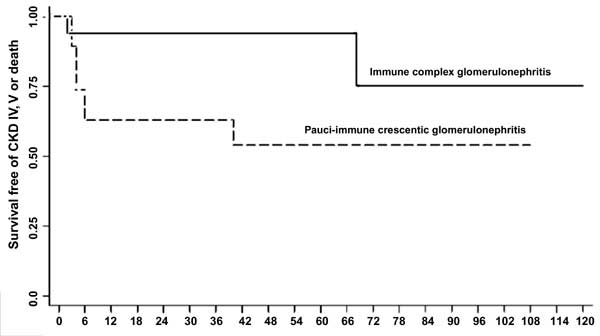

transplantation. Fig. 1 shows that renal survival was

94.1% at 1, 3 and 5-yr, and 75.3% at 8 and 10-yr in patients with immune

complex crescentic GN. Renal survival in patients with pauci-immune GN

was lower at 63.2% at 1 and 3-yr, and 54.1% at 5 and 8-yr (log rank

test; P=0.054).

|

|

Fig. 1 Kaplan Meier survival estimates for proportion

of patients with renal loss (chronic kidney disease stage 4 and

5) or death in patients with immune complex (solid line) and

pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis (interrupted line)

(log rank test P=0.054).

|

On univariate analysis, factors predicting renal loss

were presentation with oliguria (HR 10.5; 95% CI 1.16-95.25; P=0.037),

need for dialysis at presentation (HR 6.33; 1.27-31.57; P=0.024),

and the proportion of glomeruli showing fibrous or fibrocellular

crescents (HR 4.74; 0.99-22.52; P=0.050). Renal loss was

inversely correlated to the proportion of normal glomeruli (HR 0.91,

0.83-0.99; P=0.042). There was no relation between renal loss and

the presence of hypertension (P=0.22) at disease onset.

Discussion

The present report describes the etiology and outcome

of disease in children with crescentic GN evaluated at a single center

over nine years. A similar proportion of patients had pauci-immune and

immune complex GN. These findings are in contrast to previous case

series in children (Web Table I) showing that immune

complex GN constitutes the majority of cases with crescentic GN. The

causes for immune complex GN are varied and include post-infectious GN,

systemic lupus erythematosus, IgA nephropathy, Henoch Schonlein syndrome

and membranoproliferative GN [1-5, 8, 15]. Pauci-immune crescentic GN,

characterized by absence of significant glomerular immune deposits, is a

severe illness that represents an important cause of crescentic GN in

adults [6,7,16,17]. Data on pauci-immune crescentic GN is limited in

children, with most previous reports suggesting that these account for

4.6-20% of all cases [1-3,5,8]. Therefore our finding, that pauci-immune

GN constitutes more than one-half of all cases with crescentic GN,

suggests a changing etiologic profile of the illness in children.

However, the change in proportions might reflect a decline in rates of

post-infectious GN [18]. Alternatively, it may represent a referral

bias, with more cases with severe presentation, and therefore, a higher

proportion of patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN, being referred

to a tertiary care center.

A large proportion of patients with pauci-immune

crescentic GN have circulating ANCA. Since early 1990s, the application

of immunofluorescence and ELISA to detect ANCA and define its

specificities, has allowed diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis,

including microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener’s granulomatosis and renal

limited vasculitis [6, 10, 14]. However, a recent review suggests that

10-30% patients with pauci-immune GN are negative for ANCA [19].

Compared to those who are ANCA positive, patients with negative serology

are younger, show less constitutional and extrarenal symptoms, have

higher proteinuria and severe lesions on histology, and an

unsatisfactory renal survival [19, 20]. A recent report from northern

India showed that 21 of 48 adults with pauci-immune rapidly progressive

GN were negative for ANCA [21]. The diagnosis of ANCA negative serology

is chiefly based on negative results on immunofluorescence [19-22].

Based on this examination, and confirmed in most by specific ELISA,

84.2% of the present patients with pauci-immune GN were negative for

ANCA. While the outcome of patients with ANCA negative pauci-immune

crescentic GN is considered unsatisfactory, we did not demonstrate

differences in view of small patient numbers.

Outcomes in crescentic GN are generally

unsatisfactory and progressive renal failure has been seen in 18.9-86% (Web

Table I) [1-5,8,15]. One-third of the present patients, followed

for median duration of three years, progressed to CKD 4-5. Compared to

our previous experience [4], the improved outcomes may reflect intensive

immunosuppressive therapy and early institution of dialysis and/or

plasmapheresis. We also found that outcome of patients with pauci-immune

GN was less satisfactory compared to immune complex GN. Of 19 patients

with the former, 8 progressed to CKD stage 4-5, compared to only 2 of 17

with the latter. The findings are similar to that in adult patients,

where pauci-immune GN has inferior outcome compared to immune complex GN

[6]. While the cellularity of crescents is a marker of outcome [1-3],

the proportion of fibrous and fibrocellular crescents was similar in

pauci-immune and immune complex GN (42.1% versus 53%) and was

unlikely to account for difference in outcomes. Other predictors of

prognosis in the present cases were similar to those reported

previously, including dialysis dependence at onset [2, 4, 6] and

proportion of normal glomeruli [23].

The current report highlights the change in

etiological profile of crescentic GN in children that mirrors trends in

adult onset disease. The distinction between subtypes based on

immunofluorescence and serological findings has important implications

for therapy and outcome. Patients with pauci-immune GN show a higher

risk of progressive kidney disease. Further studies are necessary to

characterize the natural history of disease in children with

ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic GN.

Contributors: AS and KP retrieved information

from case records, collated and analyzed the data. PH and AB provided

analytical inputs and guided in analysis and review of literature. AKD

reviewed and interpreted histological specimens. All authors contributed

to the preparation of the manuscript, provided significant inputs during

preparation for final publication and approved the final manuscript. AB

supervised the study and shall be its guarantor.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis,

characterized pathologically by crescentic glomerulonephritis,

is an important cause of acute kidney injury in childhood.

• The commonest cause of crescentic

glomerulonephritis in childhood is post-infectious

glomerulonephritis, associated with deposition of immune

complexes.

What This Study Adds?

• Pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis

is an important cause of crescentic glomerulonephritis in

children.

• A large proportion of patient with pauci-immune

crescentic glomerulonephritis may be negative for antineutrophil

cytoplasmic antibodies.

• The outcome of patients with pauci-immune

crescentic glomerulonephritis is unsatisfactory compared to

those with immune complex crescentic glomerulonephritis.

|

References

1. Dewan D, Gulati S, Sharma RK, Prasad N, Jain M,

Gupta A, et al. Clinical spectrum and outcome of crescentic

glomerulonephritis in children in developing countries. Pediatr Nephrol.

2008;23:389-94.

2. Jardim HM, Leake J, Risdon RA, Barratt TM, Dillon

MJ. Crescentic glomerulonephritis in children. Pediatr Nephrol.

1992;6:231-5.

3. A clinico-pathologic study of crescentic

glomerulonephritis in 50 children. A report of the Southwest Pediatric

Nephrology Study Group. Kidney Int. 1985;27:450-8.

4. Srivastava RN, Moudgil A, Bagga A, Vasudev AS,

Bhuyan UN, Sunderam KR. Crescentic glomerulonephritis in children: a

review of 43 cases. Am J Nephrol. 1992;12:155-61.

5. Tapaneya-Olarn W, Tapaneya-Olarn C, Boonpucknavig

V, Boonpucknavig S. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in Thai

children. J Med Assoc Thai. 1992;75:32-7.

6. Jennette JC. Rapidly progressive crescentic

glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1164–77.

7. Koyama A, Yamagata K, Makino H, Arimura Y, wada T,

Nitta K, et al. Japan RPGN Registry Group. A nationwide survey of

rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in Japan: etiology, prognosis and

treatment diversity. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13:633-50.

8. Alsaad K, Oudah N, Al Ameer A, Fakeeh K, Al Jomaih

A, Al Sayyari A. Glomerulonephritis with crescents in children: etiology

and predictors of renal outcome. ISRN Pediatr. 2011;

doi:10.5402/2011/507298.

9. Gupta R, Singh L, Sharma A, Bagga A, Agarwal SK,

Dinda AK. Crescentic glomerulonephritis: A clinical and

histomorphological analysis of 46 cases. Ind J Pathol Microbiol.

2011;54:597-61.

10. Savige J, Pollock W, Trevisin M. What do

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) tell us? Best Pract Res

Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19:263–76.

11. Bagga A, Mantan M. Nephrotic syndrome. Indian J

Med Res. 2005;122:13-28.

12. National High Blood Pressure Education Program

Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The

fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood

pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555-76.

13. Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ,

Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the

classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum.

1982;25:1271-7.

14. Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, Bagga A, Barron K,

Davin JC, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the

classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:

936–41.

15. Miller MN, Baumal R, Poucell S, Steele BT.

Incidence and prognostic importance of glomerular crescents in renal

diseases of childhood. Am J Nephrol. 1984;4:244-7.

16. López-Gómez JM, Rivera F; Spanish Registry of

Glomer-ulonephritis. Renal biopsy findings in acute renal failure in the

Cohort of patients in the Spanish registry of glomer-ulonephritis. Clin

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3: 674-81.

17. Lin W, Chen M, Cui Z, Zhao M-H. The

immunopathological spectrum of crescentic glomerulonephritis: a survey

of 106 patients in a single Chinese center. Nephron Clin Pract.

2010;116:c65–c74.

18. Kanjanabuch T, Kittikowit W, Eiam-Ong S. An

update on acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis worldwide. Nat Rev

Nephrol. 2009;5:259–69.

19. Chen M, Yu F, Wang SX, Zou WZ, Zhao MH, Wang HY.

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody–negative pauci-immune crescentic

glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007; 18:599-605.

20. Eisenberger U, Fakhouri F, Vanhille P, Beaufils

H, Mahr A, Guillevin L, et al. ANCA-negative pauci-immune renal

vasculitis: histology and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant.

2005;20:1392-9.

21. Minz RW, Chhabra S, Joshi K, Rani L, Sharma N,

Sakhuja V, et al. Renal histology in pauci-immune rapidly

progressive glomerulonephritis: 8-year retrospective study. Indian J

Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:28-32.

22. Csernok E, Ahlquist D, Ullrich S, Gross WL. A

critical evaluation of commercial immunoassays for antineutrophil

cytoplasmic antibodies directed against proteinase 3 and myeloperoxidase

in Wegener’s granulomatosis and microscopic polyangiitis. Rheumatology

(Oxford). 2002;41:1313-7.

23. Bajema IM, Hagen EC, Hermans J, Noël LH, Waldherr

R, Ferrario F, et al. Kidney biopsy as a predictor for renal

outcome in ANCA-associated necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int.

1999;56:1751-8.

|

|

|

|

|