|

Lubchenco, et al. [1]

were the first to

describe anthropometry at birth as centiles

for various gestations. These centiles, still

used widely in many centers, were based on data from live births

from an ethnically mixed group in Colorado. However, these charts

are not universally applicable because the growth potential of

the fetus is influenced by sex of the infant, ethnic group and

geographical factors.

India specific intrauterine growth curves were

constructed by many authors [2-5]. Changes in the parity, socioeconomic

and environmental conditions necessitate an update in the existing

growth charts. We planned the present study to derive a gestation

specific reference growth chart for our local population. The objective

was to construct centile charts for birthweight, length and head circumference

for infants born from 24 to 42 weeks of gestation.

Methods

This was a medical record review of the period from

July 1999 to October 2009 at a maternity and newborn level III care

hospital in South India. All consecutively live born singleton infants

from 24 to 42 weeks of gestational age during the study period were

eligible. The gestational age had been calculated in completed weeks

from the findings of the early dating ultrasound or from the last

menstrual period. Infants with major congenital anomalies and those with

uncertain gestational age were excluded. The weights had been measured

on a digital weighing machine with a variability of ± 10 grams. The head

circumference had been measured using a non- stretchable tape and

recorded in centimetres, and the length of the infant with an

infantometer in centimetres.

All the relevant risk factors [hypertensive diseases

of pregnancy, maternal medical disorders, severe anemia (Hb <7g/dL) in

the mother] were noted from the maternal and neonatal database and in

select cases, from the case records. The perinatal details were obtained

from the neonatal database.

The LMS method [6]

was applied for normalizing the raw data. The scatter

data plots and Z scores obtained from the LMS method were used to

identify the outliers. Observations lying beyond ±3 Z score were

deleted. The centiles (3rd, 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, 95th, and

97th) for the birthweight, length and head circumference were calculated

using the LMS method which uses the Box-Cox power transformation to

obtain normally distributed data within each group.

Six sets of charts were constructed defined by the

sex of the infant for the birthweight, length and head circumference.

The normal distribution of the Z scores resulting from the

fitting of the LMS models within each group was verified by obtaining

normal probability plots (Q-Q plots). Centiles were calculated using the

LMS Chart Maker software and the other analyses was carried out using

SPSS, version 16.

Results

Thirty three thousand and seven hundred and forty

infants were born alive in the hospital during the study period. 787

infants were products of multiple pregnancies and in 28 infants

gestation was either less than 24 weeks or more than 42 weeks. From the

eligible 32,925 infants, gestation was not certain in 1444 infants.

Among the remaining 31,481, the data was available for 31,391 (males,

16,054), 28,812, (males, 14,730), and 28,790 (males, 14,724) infants for

the plotting of weight, length and head circumference centiles,

respectively. After removing the outliers, the data was available for

30,016, 27,228 and 26,974 infants for the final plotting of weight,

length and head circumference centiles, respectively (Table I).

Sixty percent of the pregnancies were booked in the hospital before 20

weeks of pregnancy and 40% of the infants were born to primiparous

mothers. The number of infants with birthweight less than 2500 grams

were 5,921 (19%) and those with birthweight less than 1500 g and 1000 g

were 1,023 (3.3%) and 282 (1%) infants, respectively. The incidence of

PIH was 6.5% (n=2060) and that of diabetes and severe anemia was

5.5% (n=1736) and 1% (n=313), respectively among the

mothers of infants included in the study.

TABLE I Infants at Each Gestational Age After Removing the Outliers

|

Ges |

Weight |

Length |

Head circum- |

|

tation |

(n= 30,016) |

(n= 27,228) |

ference (n=26,974)

|

|

(weeks) |

(M/F) |

(M/F) |

(M/F) |

|

24 |

15 (9/6) |

7 (4/3) |

7 (4/3) |

|

25 |

23 (9/14) |

9 (4/5) |

9 (4/5) |

|

26 |

68 (34/34) |

36 (20/16) |

35 (19/16) |

|

27 |

56 (31/25) |

37 (20/17) |

39 (21/18) |

|

28 |

132 (81/51) |

96 (60/36) |

90 (53/37) |

|

29 |

106 (57/49) |

79 (45/34) |

82 (45/37) |

|

30 |

159 (88/71) |

133 (74/59) |

131 (71/60) |

|

31 |

166 (78/88) |

136 (69/67) |

136 (65/71) |

|

32 |

302 (154/148) |

273 (138/135) |

265 (135/130) |

|

33 |

342 (181/161) |

308 (180/128) |

308 (180/128) |

|

34 |

508 (291/217) |

494 (278/216) |

491 (280/211) |

|

35 |

712 (387/325) |

662 (349/313) |

651 (335/316) |

|

36 |

1652 (897/755) |

1537 (807/730) |

1543 (813/730) |

|

37 |

4210 (2254/1956) |

3876 (2028/1848) |

3814 (1964/1850) |

|

38 |

8002 (4024/3978) |

7316 (3657/3659) |

7221 (3620/3601) |

|

39 |

6373 (3159/3214) |

5640 (2855/2785) |

5570 (2853/2717) |

|

40 |

6580 (3366/3214) |

6023 (3056/2967) |

6030 (3088/2942) |

|

41 |

574 (281/293) |

524 (264/260) |

509 (251/258) |

|

42 |

36 (17/19) |

42 (20/22) |

43 (21/22) |

|

M-male; F-female.

|

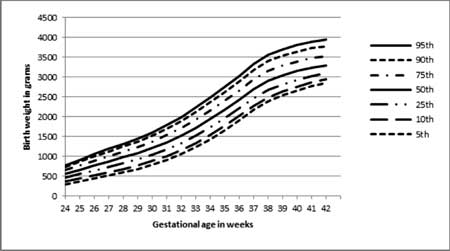

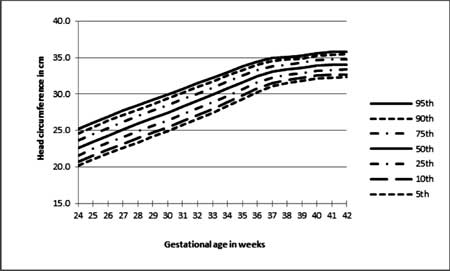

The Q-Q plot for z scores of birth weight, length and

head circumference displayed good correlation for the data between 5th

and 95th centiles. The crude curve for the raw data of male infants

displayed a bump in the 97th percentile from 30 to 32 weeks. The crude

curves of female infants were relatively smoother. Female infants were

lighter than the male infants especially from 35 weeks onwards (Fig.

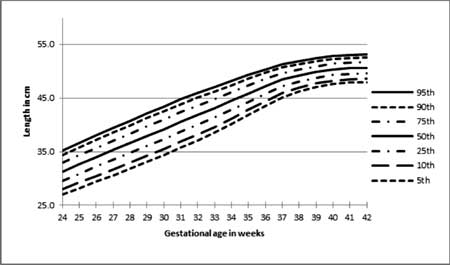

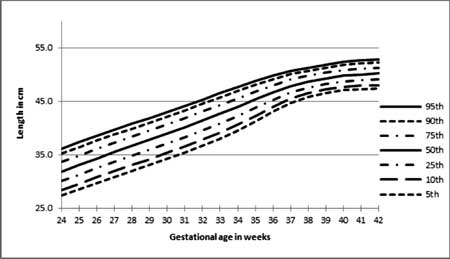

1). However, there was not much difference in the length and head

circumference (Fig. 2,3).

(a) |

(b) |

|

Fig. 1 Smoothened centile curves for the birthweight

of (a) male and (b) female infants (without outliers).

|

(a) |

(b) |

|

Fig. 2 Smoothened curves for length of

(a) male and (b) female infants (outliers removed).

|

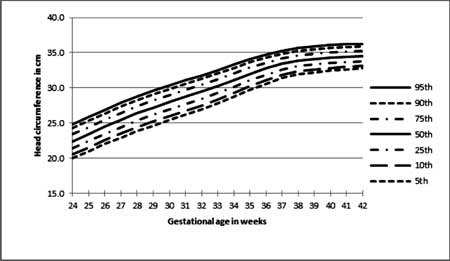

(a) |

(b) |

|

Fig. 3 Smoothened curves for head

circumference of (a) male and (b) female infants (outliers

removed).

|

On superimposing our charts on the most widely used

Lubchenco intrauterine growth charts [1], for the 10th, 50th and 90th

centiles, our preterm babies (< 35 weeks) were lighter than Colorado

babies. For late preterm and term babies (≥35

weeks), the 90th centile birthweights were lower, the 50th centile birth

weights were similar and the 10th centile birth weights were higher.

Similar pattern was noted for both the sexes. However, length and head

circumference centiles were similar to that of Lubencho, et al.

for lower gestational ages (< 35weeks) and at term gestation, study

centiles were higher or similar.

On comparing the weight centiles with the Canadian

[7]

and Scottish [8] data, birthweights were lower across all

the gestations and centiles. Superimposition of study centiles of male

infants on the recently published North American centiles [9] revealed,

lower birthweights for the 50th and 90th centiles at term gestation and

similar birthweights for the 10th centile across all gestations.

However, the length and head circumference centiles were similar across

all gestations and centiles.

Discussion

The study presents the centiles, means, standard

deviations and smoothened curves of birth anthropometry in a large

cohort of neonates for weight, length and head circumference. It is the

first study from our country involving neonates from 24 to 42 weeks of

gestation. Another unique feature was the presence of significant number

of babies at lower gestations (<30 weeks). The study cohort was

stratified for sex unlike other Indian studies [2,3]. The study

population was representative of the population in this part of country

as evidenced by the similarity in the incidence of prematurity and

obstetric morbidities like multiple pregnancies, maternal hypertension

and maternal diabetes to the

large hospital based data from the country [10].

The study met most standards required to obtain an

ideal reference growth chart [11]. The data included singleton

babies born from a monoethnic group and most importantly the best method

for gestational age estimation (first trimester based ultrasound dating)

was used in more than 60% of the included infants as they were born of

pregnancies registered early in our hospital. Gestational assessment was

mandatory for our hospital records. The gold standard LMS method [6] was

used for estimating the centiles and for the smoothening of the centile

curves.

Most of the recent studies have shown a secular trend

of increasing birthweight at higher gestational ages. This is also

evident in our cohort. The mean birthweights after 34 weeks were higher

in our cohort compared to the previous studies [2-5]. At term

gestational age the mean birthweights were almost 100 to 200 grams

higher in our present cohort. However, at lower gestations, our birth

weights were similar or lower (Web Table I). This may be

attributed to improved survival of smaller babies at lower gestations

over the last two to three decades. Similar trends were observed for the

length at birth. There was a trend of increased length at higher

gestations. However, there was no change in head circumference centiles

across all gestations.

Most of the units in our country still use Lubchenco,

et.al. [1] charts for

classifying the infants at birth into small for gestation (SGA) and

large for gestation (LGA). However, our data in comparison with that of

Lubchenco, et al. suggest that the 10th and 90th centiles of our

babies are lower. This leads to overestimation of the incidence of SGA

and underestimation of LGA babies, the consequence being many AGA

infants labelled as SGA, and LGA infants being overlooked as they are

misclassified as appropriate for gestational age (AGA). On comparing

with the other international growth charts [7, 8], the birthweights of

our babies were lower across all the gestations and centiles. Population

specific and updated growth charts should be used for the appropriate

classification of infants into SGA or LGA or AGA.

Inspite of the best effort in calculating the

centiles using the large cohort and also best statistical methods, this

study still has few limitations. Gestational age estimation was not

ultrasound based in all the included infants. Anthropometric

measurements were done by different nurses and this may have contributed

to the inter-observer variability. We did not construct separate curves

for parity and maternal height. This is a single centre cross-sectional

study spanning 10 years. This growth data is from all the socioeconomic

strata and hence might not reflect the ideal potential for intrauterine

growth. An ideal chart should be multicentred and involve data from 2 to

5 years. Ideally, at each gestation, we would require 100 babies for

estimating all the centiles. Our data lacks this parameter at lower

gestations (less than 32 weeks). We did not include stillbirths in our

data for the ease of data collection, as it was retrospective.

Contributors: SM and GK designed the study. HK

collected the data. SM and SS monitored the data collection. HK and SM

analyzed data and wrote the manuscript with inputs from SS.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What is Already Known

• Multiple growth centiles are available for

weight, length and head circumference at birth.

What This

Study Adds?

• The updated sex-specific centile charts in

this study may be used as reference curves for various

gestational for the birthweight, length and head circumference,

in South Indian infants.

|

References

1. Lubchenco L, Hansman C, Dressler M, Boyd E.

Intrauterine growth as estimated from live born birth weight data at 24

to 42 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 1963;32:793-800.

2. Ghosh S, Bhargava SK, Madhavan S, Taskar AD,

Bhargava V, Nigam SK. Intrauterine growth of north Indian babies.

Pediatrics. 1971;47:826-32.

3. Singh M, Giri SK, Ramachandran K. Intrauterine

growth curves of live born single babies. Indian Pediatr.1974;11:475-9.

4. Mohan M, Shiv Prasad SR, Chellani HK, Kapani V.

Intrauterine growth curves in north Indian babies: weight, length, head

circumference and ponderal index. Indian Pediatr.1990;27:43-51.

5. Mathai M, Jacob S, Karthikeyan NG. Birthweight

standards for south Indian babies. Indian Pediatr.1996;33:203-9.

6. Cole TJ. Fitting smoothed centile curves to

reference data. J R Stat Soc. 1988;151:385-418.

7. Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, Joseph KS. A new and

improved population-based Canadian reference for birthweight for

gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001;108;e35.

8. Bonellie S, Chalmers J, Gray R, Greer I, Jarvis S,

Williams C. Centile charts for birthweight for gestational age for

Scottish singleton births. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2008;8:5.

9. Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel

BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data.

Pediatrics. 2010;125;e214-24.

10. National Neonatology Forum. National Neonatal-Perinatal

Database (2002-03). Available from www.newbornwhocc. org/pdf/nnpd_report_2002-03.PDF.

Accessed on 1 March, 2011.

11. Bertino E, Milani S, Fabris C, Curtis MD. Neonatal anthropometric

charts: what are they and what are they not. Arch Dis Child Fetal

Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F7-10.

|