|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56: 476-480 |

|

Comparison of Feeding Options for HIV-Exposed

Infants: A Retrospective Cohort Study

|

|

Sandip Ray, Anju Seth, Noopur Baijal, Sarita Singh,

Garima Sharma, Praveen Kumar and Jagdish Chandra

From Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical

College, New Delhi, India

Correspondence to: Dr Anju Seth, Director Professor,

Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical College,

New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: September 10, 2018;

Initial review: December 27, 2018;

Accepted: March 20, 2019.

|

|

Objectives: To compare growth,

anemia prevalence, and sickness frequency in HIV- exposed uninfected

infants on different feeding modes. Methods: In this

retrospective cohort study, 109 HIV-exposed uninfected infants

registered at our center were categorized into three

groups as per their feeding mode during first 6 months viz.

exclusively breast fed (n=50), animal milk fed (n=40) and

commercial infant formula fed (n=19). Their anthropometric

parameters, hemoglobin and frequency of sickness at the age of 6 months

were compared. Results: There were no significant inter-group

differences in the weight for age, weight for length, length for age

z-scores (P=0.16, 0.37 and 0.12, respectively); proportion of

infants with underweight (P=0.63), wasting (P=0.82), or

stunting (P=0.82), and mean hemoglobin levels among the 3 groups

at 6 month of age. Animal milk fed and formula fed infant had increased

risk of sickness compared to exclusively breastfed infants (OR 2.5 and

2.49, respectively; P<0.01). Conclusions: In circumstances

where breastfeeding is not feasible or preferred, animal milk feeding

offers a viable alternative to commercial infant feeding formula in HIV

exposed infants.

Keywords: Animal milk, Breastfeeding, Infant

feeding, Formula-milk, Growth.

|

|

W

orld Health Organization (WHO) and National AIDS

Control Organisation (NACO) recommend exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) with

provision of lifelong antiretroviral treatment as the strategy of choice

to optimize HIV-free survival among HIV-exposed infants. In situations

where mothers cannot/choose not to breastfeed, the only option

recommended by WHO for infants <6 months is commercial infant formula

(CIF). Animal milk (AMF) is not recommended as a replacement feeding

option in the first six months of life [1]. However, the cost of CIF is

prohibitive in low- and middle-income countries and it may not be

economically feasible for mothers to use CIF exclusively for the first 6

months. In its recommendations, NACO has included locally available

unmodified animal milk apart from CIF as an option for replacement

feeding [2]. The former includes fresh boiled animal milk or pre-packed

processed toned dairy milk along with multi-vitamin and iron

supplementation. The Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) Guidelines

(2010) of Indian Academy of Pediatrics also included unmodified animal

milk as an alternative option where EBF is not possible [3].

It is highly pertinent that AMF be formally evaluated

for its suitability as an alternative feeding option for HIV- exposed

infants. Otherwise, cost-cutting can compromise the infants’ growth and

development in the long run, an unacceptable consequence. This study

aimed to assess the impact of AMF on growth parameters, prevalence of

anemia and episodes of sickness in HIV-exposed infants as compared to

infants who received EBF or CIF during the first 6 months of life.

Methods

The present study is a retrospective analysis of

records of HIV-exposed infants registered at anti–retroviral therapy

center of Lady Hardinge Medical College and associated Kalawati Saran

Children’s Hospital at New Delhi during October 2007 to December 2015.

In accordance with the national policy, all

pregnant/lactating women with HIV infection and their infants registered

at our centre are given antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) for prevention of

HIV transmission to their infants [4]. They are counseled regarding

infant feeding options during pregnancy and again soon after birth by

trained counselors. In women opting for it, EBF is initiated within

first hour of birth. In situations where the woman opts for replacement

feeding or where EBF is not possible (maternal death or sickness),

feeding with locally available AMF (fresh boiled animal milk or

pre-packed processed toned dairy milk containing 3% fat, 3.1% protein

providing 58 kcal/100 mL) or CIF is decided upon after discussion with

the family depending upon their socio-economic condition and

socio-cultural factors [2]. Depending upon the opted feeding method, the

family is counseled regarding correct breastfeeding practices, avoidance

of mixed feeding and proper method of preparing and administering RF

using katori-spoon. Multi-vitamins to meet the RDA are started at

birth/time of registration at our centre and iron supplementation at the

rate of 2 mg/kg/day is prescribed at 6 weeks of age to all infants on

AMF. The compliance to feeding practices and supplements is ensured at

time of each contact by taking regular feedbacks and targeted

counseling.

For this study, we reviewed records of all

HIV-exposed infants registered at our ART centre within 15 days of birth

and followed up till at least 6 months of age. We excluded infants who

were lost to follow-up, who had less than two growth parameter reading

during the 6-month period, those who were given mixed feeding, and those

whose final HIV status was not determined at six months of age.

There was a change in National policy for prevention

of parent to child transmission of HIV (PPTCT) during this time. Prior

to January 2014, all women with HIV and their newborns were given a

single dose of nevirapine (NVP) during labour and immediately after

birth, respectively. After January 2014, all HIV-infected pregnant women

were initiated on ART soon after detection of their HIV status [4].

Infants born to these women were started on daily NVP prophylaxis at

birth and continued for a minimum of 6 weeks. Mothers who were detected

to be HIV-infected during labour/after delivery were started on ART upon

detection and their infants were given NVP prophylaxis. The study

therefore included data from participants registered before and after

change in recommendations. Determination of HIV status was done through

virological tests [4] i.e. HIV-1 DNA PCR by dried blood spot followed by

confirmation on whole blood if positive, at ages 6 weeks, 6 months and 6

weeks after stopping breastfeeding. The enrolled infants were classified

into three groups on basis of feeding strategy adopted during first 6

months following birth: (i) EBF: Infants exclusively breastfed; (ii)

AMF: infants receiving fresh animal milk (cow, buffalo or goat milk) or

commercially available pre-packed toned milk fed after boiling without

any modification; and (iii) CIF: infants receiving

age-appropriate commercially available infant feeding formula.

The nutritional status of infants was determined by

calculating z-scores for weight for age (WFA), weight for length (WFL)

and length for age (LFA) at birth and 6 months using WHO growth

reference standards [5], and prevalence of underweight (WFA <–2

z-score), wasting (WFL <–2 z-score) and stunting (LFA <–2 z-score) was

estimated. Episodes of sickness and serious sickness (requiring

hospitalization) till 6 months age, mean serum hemoglobin at 6 (±1)

months and grading of anemia severity as per WHO guidelines was also

assessed among the study infants [6]. The study protocol was approved by

the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Statistical analysis: Paired t-test was

used to compare the WFA, WFL and LFA z-scores of infants at birth and

six months in each feeding group. Analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) was

used to compare the z-scores at six months among the three

feeding groups taking baseline z-score at birth as co-variant.

McNemar test was applied to compare the proportion of babies with

underweight, wasting and stunting at birth with that at six months.

Fisher Exact test was used to compare the proportion of babies with

underweight, wasting and stunting at six months among the three feeding

groups and for comparison of disease specific morbidities among the

three groups. For comparing the episodes of illness in infants among

different feeding groups, Poisson regression method was adopted. SPSS

version 23.0 (IBM, New York, USA) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

We evaluated case records of 189 infants (105 males)

for this study. At 6 months of age, 109 (57.7%) among these were

confirmed to be HIV-negative and 4 HIV-positive, while status of

remaining 76 infants was not determined. All the infants were

intra-mural referrals except 2 (4%) in EBF group. Baseline

characteristics of the 109 HIV-exposed uninfected infants included for

analysis are described in Table I. There was no mortality

among these infants during the first 6 months of age.

TABLE I Baseline Characteristics of Hiv-exposed Uninfected Infants (N=109)

|

Parameters, n (%) |

AMF (n=40) |

CIF (n=19) |

EBF(n=50) |

P value |

|

Vaginal delivery |

9 (22.5) |

7 (36.8) |

27 (54) |

|

|

Caesarean section |

31 (77.5) |

12 (63.2) |

23 (46) |

|

|

ART therapy in mothers* |

|

|

|

|

|

Started antenatally |

26 (65) |

13 (68.4) |

41 (82) |

|

|

Started perinatally |

12 (30) |

6 (31.6) |

6 (12) |

|

|

Not on ART at registration |

2 (5) |

0

|

3 (6) |

|

|

ARV prophylaxis status in infants |

|

|

|

|

|

Single dose nevirapine at birth |

19 (47.5) |

5 (26.3) |

14 (28) |

|

|

Nevirapine for 6-12 weeks after birth (with maternal ART) |

18 (45) |

12 (63.2) |

33 (66) |

|

|

Zidovudine till 12 wks age |

3 (7.5) |

2 (10.5) |

3 (6) |

|

|

Male infants |

25 (62.5) |

12 (63.1) |

29 (58) |

|

|

Gestational maturity, (n=30) |

|

|

|

|

|

Full-term |

11 (68.7) |

5 (83.3) |

6 (75) |

0.92 |

|

Preterm |

5 (31.3) |

1 (16.7) |

2 (25) |

0.47 |

|

Birthweight |

|

|

|

|

|

<2.5 kg (Low birth weight) |

11 (27.5) |

5 (20.3) |

15 (30) |

0.18 |

|

≥2.5 kg |

29 (72.5) |

14 (73.6) |

35 (70) |

0.95 |

|

Age at registration at ART center (d), mean (SD) |

3.1 (1.9) |

2.7 (1.7) |

2.3 (2.2) |

0.18 |

|

Anthropometric parameters at birth, mean (SD) |

|

|

|

|

|

Birthweight (kg) |

2.6 (0.5) |

2.7 (0.6) |

2.7 (0.4) |

0.68 |

|

WFA z-score

|

-1.3 (1.4) |

-1.3 (1.6) |

-1.3 (1.1) |

0.98 |

|

WFL z-score

|

-1.5 (1.3) |

-1.0 (1.6) |

-1.0 (1.3) |

0.21 |

|

LFA z-score

|

-0.7 (1.1) |

-0.4 (1.0) |

-1.0 (1.4) |

0.18 |

|

Underweight, n (%) |

8 (20) |

4 (21) |

13 (26) |

0.41 |

|

Washed, n (%)

|

11 (31.4) |

5 (29.4) |

9 (21.9) |

0.40 |

|

Stunted, n (%)

|

4 (10.8) |

0

|

8 (17.7) |

0.53 |

|

*ART consisting of: T (Tenofovir), L (Lamivudine), E (Efavirenz);

AMF: Animal milk; CIF: Commercial infant formula; EBF: Exclusive

breastfeeding. |

The anthropometric parameters in the three feeding

groups at 6 months, and mean change in z-scores at 6 months compared to

birth are shown in Table II. There was no difference in

LFA, WFA or WFL z-scores or in proportion of infants with underweight,

wasting or stunting at the age of six months among the three groups (Table

II).

TABLE II Comparison of Anthropometric Parameters at 6 Months of Age Among the Study Infants

|

Parameters |

AMF |

CIF |

EBF

|

P |

|

(n=40) |

(n=19) |

(n=50) |

value |

|

WFA z-score |

-1.5 (1.4) |

-0.7 (1.7) |

-1.4 (1.4) |

0.16 |

|

Change in z-score* |

-0.2 (1.8) |

0.5 (1.1) |

-0.1 (1.1) |

|

|

WFL z-score |

-0.7 (1.4) |

-0.2 (1.4) |

-0.7 (1.4) |

0.37 |

|

Change in z-score* |

0.8 (2.5) |

1 (1.4) |

0.5 (1.5) |

|

|

LFA z-score |

-1.4 (1.4) |

-0.8 (1.7) |

-1.4 (1.0) |

0.12 |

|

Change in z-score* |

-0.6 (1.3) |

-0.2 (1.4) |

-0.6 (0.9) |

|

|

Underweight (%) |

29.4 |

26.7 |

37.8 |

0.63 |

|

Wasting (%) |

16.7 |

7.1 |

18.9 |

0.82 |

|

Stunting (%) |

31.2 |

28.6 |

30 |

0.82 |

|

*as compared to birth z-score WFA; weight for age, WFL: weight

for length, LFA: length for age; AMF: fresh animal milk fed,

CIF: commercial infant formula fed, EBF: exclusively breast fed. |

Tables III shows frequency and nature of

illness among infants in the study groups. Two infants required

hospitalization during the study period, 1 each for sepsis (EBF group)

and diarrhea (AMF group). The AMF infants had higher odds (OR 2.5; 95%

CI: 1.4-4.4) of having an episode of illness compared to EBF group.

Likewise, CIF infants had higher odds (OR 2.49; 95% CI: 1.3-4.8) of

having an episode of illness compared to EBF group. There was no

significant difference between frequency of sickness among the AMF and

CIF groups.

TABLE III Comparison of Morbidity Profile Among the Study Infants During First 6 Months of Life

|

Illness type |

AMF

|

CIF |

EBF

|

|

(n=40) |

(n=19) |

(n=50) |

|

Total morbidities |

36 |

17 |

18 |

|

Number of episodes/child / 6 mo

|

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.4 |

|

Diarrhea* |

28 |

6 |

7 |

|

LRTI |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

URTI |

6 |

3 |

5 |

|

Meningitis |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Skin (pyoderma/scabies) |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Sepsis |

0 |

2 |

1 |

|

Otitis media |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

LRTI: lower respiratory tract infections;

URTI: upper respiratory tract infections; *significantly

different among the 3 study groups (P<0.001).

|

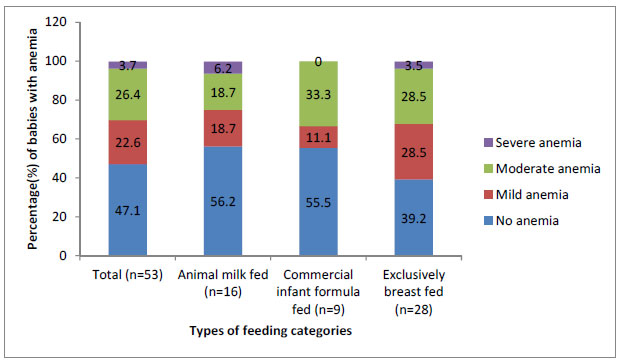

Hemoglobin levels at 6 months were available for 53

infants (AMF 16, CIF 9, EBF 28). Mean (SD) hemoglobin levels in infants

of AMF, CIF and EBF groups were 10.8 (1.41) g/dL, 11.0 (1.06) g/dL

and 10.2 (1.1) g/dL, respectively. There was no significant difference

in the mean hemoglobin level as well as proportion of infants with

different grades of anemia among the three groups (Fig. 1).

|

|

Fig. 1 Proportion of infants with

different grades of anemia in different feeding categories.

|

Discussion

TThis study documented no significant difference in

growth parameters or prevalence of anemia in HIV-exposed infants on AMF

as compared to CIF or EBF during first 6 months of life. Despite ongoing

feeding counseling, incidence of sickness, especially diarrhea, was

significantly higher in infants on AMF and CIF as compared to those on

EBF. There was no evidence of any significant difference between AMF and

CIF with respect to frequency of sickness.

The search for an option for replacement feeding that

would be culturally acceptable, economically viable while being

nutritionally adequate, is a felt need for HIV exposed infants [7]. AMF

has been widely used for infant feeding by women with HIV infection

[8,9]. Papathakis, et al. [10] have shown home prepared

modifications of evaporated milk, powdered full cream milk and fresh

full cream milk to be deficient in vitamins and essential minerals. We

could not find any published work which has reported on growth

parameters or anemia prevalence among infants (HIV-exposed or otherwise)

fed on animal milk. While no difference has been reported in

anthropometric parameters of HIV-exposed infants on EBF or CIF from

South Africa [11], higher weight for height z-scores over a two year

follow-up have been reported in breast fed as compared to formula fed

infants from Kenya [12]. No difference in anemia prevalence has been

reported in infants fed on EBF and CIF [11,13]. An increased risk of

morbidity and hospitalization in HIV-exposed infants on replacement

feeding, compared to those on EBF, has been shown in a previous Indian

study [9]. Studies from other parts of the world have also shown higher

frequency of respiratory tract infections [14] and diarrhea [11,12,14]

in non-breastfed infants. WHO has published a meta-analysis showing

breastfeeding to be protective against deaths due to infectious

diseases, the odds being significantly more in first six months of life

than in later ages [15].

Despite widespread use of animal milk in infant

feeding, especially in context of maternal HIV infection, the evidence

for suitability of animal milk as an option for replacement feeding in

HIV-exposed infants is lacking. Retrospective nature of data is a major

limitation of this study. While we have demonstrated that use of AMF

along with multi-vitamin and iron supplementation in HIV- exposed

infants leads to an equivalent growth, anemia prevalence and similar

morbidity outcomes as compared to CIF, we have not been able to assess

the status of other micro-nutrients in these infants. We have also not

measured serum ferritin levels, a better marker for iron deficiency.

This work provides data that AMF along with iron and

multivitamin supplementation is a possible alternative to CIF in

HIV-exposed infants where breastfeeding is not feasible/opted for.

However, there is a need to standardize the nutrient value of these milk

preparations as well as study the micronutrient status of the infants

fed exclusively on AMF, so that holistic growth and development of an

infant does not suffer.

Contributors: SR: extracted the data, analyzed it

and drafted the paper; AS: conceptualized the paper, was overall

responsible for quality of data collection and maintenance, modified &

finalized the draft; NB, SS, GS: clinical care, and data recording and

analysis; JC, PK: patient care, quality maintenance and modification of

draft of the paper. All authors provided inputs to manuscript writing,

and its final approval.

Funding: None; Competing

interest: None stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Animal milk feeding, along with iron and

multivitamin supplementation, offers a viable alternative to

commercial infant feeding formula in terms of anthropometric and

morbidity-related outcomes in HIV-exposed infants.

|

References

1. World Health Organization, United Nations

Children’s Fund. Guideline: updates on HIV and Infant Feeding: The

Duration of Breastfeeding, and Support from Health Ser-vices to Improve

Feeding Practices Among Mothers Living With HIV. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 2016./p>

2. National AIDS Control Organization. Nutrition

Guidelines for HIV-Exposed and Infected Children (0-14 Years of Age).

Available from:

http://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/Paedia%20Nutrition%20national%20guidelines%20

NACO.pdf. Accessed January 07, 2013.

3. Rajeshwari K, Bang A, Chaturvedi P, Kumar V, Yadav

B, Bharadva K, et al. Infant and Young Child Feeding Guidelines:

2010. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:995-1004.

4. National AIDS Control Organization-Updated

Guidelines for Prevention of Parent to Child Transmission (PPTCT) of HIV

Using Multi-drug Anti-retroviral Regimen in India, December 2013.

Available from: i>

http://naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/National_Guidelines_for_PPTCT_0.pdf.

Accessed April 04, 2018.

5. World Health Organization. WHO Child Growth

Standards. 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/child

growth/standards/Technical_report.pdf. Accessed 04 April, 2018.

6. World Health Organization. Hemoglobin

Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anemia and Assessment of Severity:

WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.1. Available from:

http://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf.. Accessed April

04, 2018.

7. Cames C, Mouquet-Rivier C, Traore T, Ayassou KA,

Kabore C, Bruyeron O, et al. A sustainable food support for

non-breastfed infants: implementation and acceptability within a WHO

mother-to-child HIV transmission prevention trial in Burkina Faso.

Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:779-86.

8. Van Hollen C. Breast or bottle? HIV-positive

women’s responses to global health policy on infant feeding in India.

Med Anthropol Q. 2011;25:499-518.

9. Phadke MA, Gadgil B, Bharucha KE, Shrotri AN,

Sastry J, Gupte NA, et al. Replacement-fed infants born to

HIV-infected mothers in India have a high early postpartum rate of

hospitalization. J Nutr. 2003;133:3153-7.

10. Papathakis PC, Rollins NC. Are WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF

recommended replacement milks for infants of HIV-infected mothers

appropriate in the South African context? Bull World Health Organ.

2004;82:164-71.

11. Kindra G, Coutsoudis A, Esposito F, Esterhuizen

T. Breastfeeding in HIV exposed infants significantly improves child

health: A prospective study. Matern Child Health J.i>

2012;16:632-40.

12. Mbori-Ngacha D, Nduati R, John G, Reilly M,

Richardson B, Mwatha A, et al. Morbidity and mortality in

breastfed and formula-fed infants of HIV-1- infected women: A randomized

clinical trial. JAMA. 2001;286:2413-20.

13. Nduati R, John G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Richardson B,

Overbaugh J, Mwatha A, et al. Effect of breastfeeding and formula

feeding on transmission of HIV-1: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA.

2000;283:1167-74.

14. Becquet R, Bequet L, Ekouevi DK, Viho I,

Sakarovitch C, Fassinou P, et al. Two-year morbidity-mortality

and alternatives to prolonged breast-feeding among children born to

HIV-infected mothers in Cote d’Ivoire. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e17.

15. WHO Collaborative Study Team on the Role of

Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality. Effect of

breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases

in less developed countries: A pooled analysis. Lancet. 2000;355:451-5.

|

|

|

|

|