T

he limited access, insufficient availability,

sub-optimal or unknown quality of health services, and high

out-of-pocket expenditure (OOPE) are amongst the key health challenges

in India [1]. These challenges exist alongside a global discourse to

achieve universal health coverage (UHC) – increasing access to quality

healthcare services at affordable cost, by all people; and in times of

fast economic growth in India [2]. Though, India’s National health

policy-2017 (NHP-2017) is fully aligned with global discourse and has

the goal to achieve UHC, outside the policy discourses, health is often

not considered high on the priorities by political leadership and is

traditionally been underfunded [1,3,4]. The inappropriate mix of inputs

(infrastructure, human resources and supplies) results in a failure to

deliver the desired health services and public health system is grossly

underutilized by people. The elaborate government primary healthcare

system in rural India with nearly 185,000 facilities delivers only 8-10%

of total health services, availed by people. One-fourth of health

facilities in public sector deliver nearly three-fourths of total health

services delivered by entire public sector facilities. This means that

remaining 75% of health facilities are delivering much lower number of

services per facility than these are capable of [5]. People are either

compelled to, or prefer to, seek care from private providers, often at a

cost beyond their paying capacity. Health expenditure is estimated to

contribute to 3.6% and 2.9% of rural and urban poverty, respectively

[6]. Annually, an estimated 60 to 80 million people in India either

falls into poverty or get deeper into poverty (if already below poverty

line) due to health-related expenditures [1,7]. Clearly, the health

expenditures undermine poverty alleviation efforts by the union and

state governments in India (Box 1) [1,8-17]. India was

ranked at 154 of 195 countries on health service delivery index

published in mid-2017 in Lancet journal [18]. Though Indian healthcare

system has traditionally focused on delivery of maternal and child

health (MCH) services, and in spite of making rapid progress, the

country continues to have relatively high infant and maternal mortality

[19]. Access to even child health services is mostly through private

sector. Furthermore, people often have to spend from their pockets for

services such as child birth, even when availing services at public

health facilities [20,21].

|

Box 1 Key Health Challenges in India [1,8-17]

Health infrastructure and human resources:

There were 156,231 SHCs, 25,650 PHCs and 5,624 CHCs in India as

on 31st March 2017 [8]. However, most of these facilities suffer

from poor infrastructure, under-staffing and lack of equipment

and medicines. Only 11% of SHC, 16% of PHCs and 16% CHCs meet

the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS) [5]. There is gross

shortage of specialists and general physicians in all levels of

system. More specifically, SHC, which are the first contact

point between community and government health system, one-fifth

were without regular water supply, one fourth without

electricity, one in every ten without all-weather road, and over

6,000 did not have an Auxiliary Nurse Midwife/health worker

(female) [8,10].

Health financing: The high out of pocket

expenditure (OOPE) on health at 62.6% of total health

expenditure is a major health challenge in India [11]. The OOPE

on health in India is one of the highest in the world and nearly

thrice of global average of 20.5% [8]. Part of the reason is

poor government spending on health, at 1.15% of gross domestic

product (GDP), which is one of the lowest in the world

[1,11,12].

Service Delivery and utilization: In

absence of well-functioning government facilities, people chose

private providers. Nearly 75% of all out-patient consultations

and 65% of all hospitalization in India happens in private

sector [13]. People in India are increasingly getting affected

by the health conditions which require regular visits to

out-patient consultation, preventive and promotive measures and

regular medications. The cost of such high volume and low-cost

interventions is major part of OOPE.

Quality of health services: There

is limited information available about quality of healthcare

services in India [14]. However, widespread presence of

unqualified providers, shortage of human resources, absentee

doctors, and studies on skills of qualified doctors indicates

toward poor quality of health services [14,15]. Regulation

is an approach to ensure quality; however, the clinical

establishment (registration and regulation) act 2010 has been

implemented by only a limited number of states in India [16].

Changing disease epidemiology: The

changing epidemiological profile of population is another

reality in India. In 2016, the non-communicable diseases were

major causes of morbidity and mortality in all Indian states

replacing the communicable diseases abundance [17].

|

In this background, when Ayushman Bharat

Program (ABP) was announced in India’s union budget 2018-19, it received

wide and unprecedented media, public and political attention [22-24].

This article reviews and documents the key health sector related

announcements in union budget 2018-19, critically analyzes the

components of the proposed program, and suggests a few strategies to

strengthen implementation and accelerate India’s journey towards UHC.

Health in Union Budget of India (2018-19)

The Government of India’s union budget, for the

financial year 2018-19, was presented to the parliament of India on 1st

February 2018 [22]. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare received

an allocation of Rs. 54,800 Crore (approx. US $ 8.4 billion), an

increase of nearly 11.5 percent over the budget of last year. Though in

nominal terms, the budgetary allocation to health sector has trebled in

the last decade (Table I); as proportion of gross domestic

product (GDP), it has changed marginally from 1.1% to 1.3% [22-25].

TABLE I Budget Allocation to Health Sector in India 2008-09 to 2018-19 [22-24]

|

Financial |

Ministry/Department |

Total |

|

Year |

Health & |

Health

|

AYUSH* |

AIDS |

|

|

Family Welfare |

Research |

|

Control** |

|

|

2008-09 |

16968 |

531 |

623 |

- |

18123 |

|

2009-10 |

21113 |

606 |

922 |

- |

22641 |

|

2010-11 |

23530 |

660 |

964 |

- |

25154 |

|

2011-12 |

26897 |

771 |

1088 |

1700 |

30456 |

|

2012-13 |

30702 |

908 |

1178 |

1700 |

34488 |

|

2013-14 |

33278 |

1008 |

1259 |

1785 |

37330 |

|

2014-15 |

35163 |

1017 |

1272 |

1785 |

39237 |

|

2015-16 |

29653 |

1018 |

1214 |

1397 |

33282 |

|

2016-17 |

37061 |

1144 |

1326 |

- |

39533 |

|

2017-18 |

47352 |

1500 |

1428 |

- |

50281 |

|

2018-19 |

52800 |

1800 |

1626 |

- |

56226 |

All figures in Indian Rupee x Crores. The values are actuals

for 2008-09 till 2016-17 and budget estimates for year 2017-18

and 2018-19.

Remark: Fourteenth Finance Commission recommended the devolution

of 42% of total central revenue resources, which was implemented

starting FY 2015-16. This artificially resulted in reduced

allocation to centrally sponsored schemes in union budget.

* Ministry of AYUSH was created in 2015-16. The budget of the

Department of AYUSH is shown prior to these years; **Department

of AIDS Control (i.e., NACO) had a separate Demand for Grant in

Union Budget in the specified years |

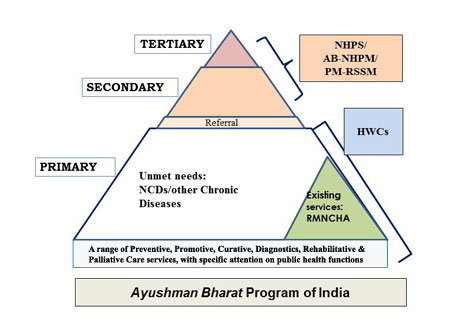

A key announcement in the union budget 2018-19 has

been the Ayushman Bharat Program (ABP). This program has two components:

(a) delivering comprehensive primary health care by establishing

150,000 health and wellness centers (HWCs) by year 2022, and (b)

Providing financial protection for secondary and tertiary level

hospitalization as part of National Health Protection Scheme (NHPS). The

ABP with two components intends to provide services with continuum

across three levels of care and brings back the attention on delivery of

entire range of preventive, promotive, curative, diagnostic,

rehabilitative and palliative care services (Fig. 1).

|

|

NHPS: National Health protection Scheme;

AB-NHPM: Ayushman Bharat- National Health Protection Mission;

PM-RSSM: Pradhan Mantri- Rashtriya Swasthya Suraksha Mission;

HWCs: Health and Wellness Centres; RMNCHA: reproductive,

maternal, neonatal, child health and adolescent; NCDs: Non

communicable diseases

Fig. 1 Ayushman Bharat Program in

India.

|

One of the two initiatives in ABP is to upgrade

150,000 (of the existing 180,000) Sub health centers (SHCs) and Primary

health centers (PHCs) in India, to the HWCs by December 2022. The scope

of services from existing SHCs and PHCs is proposed to be broadened from

current range of services, and implements the national health programs

to a broad package of 12 services. This intends to make comprehensive

primary healthcare accessible by community within 30 min of walking

distance [1,5,22]. A total of 11,000 and 16,000 HWCs are proposed to be

made functional in financial years (FY) 2018-19 and 2019-20,

respectively [26]. This includes upgrading all 4,000 primary health

centers in urban area to the HWCs by March 2020.

The second initiative in ABP is NHPS (also known as

AB-NHPM or PM-RSSM), which has been referred as ‘the world’s largest

government-funded healthcare (insurance) program’ [22]. The NPHS aims to

provide a coverage of up to Indian Rs. 500,000 (or US$ 7,700) per family

per year for expenses related to secondary- and tertiary-level

hospitalization. The AB-NHPM, after the launch would subsume Rashtriya

Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY), and the Senior Citizen Health Insurance

Scheme (SCHIS) [27-29]. The RSBY was providing insurance coverage of Rs.

30,000 (US$ 470) for up to 5 members of a family per annum, for a target

beneficiary base of 60 million families. The target beneficiary in

AB-NHPM has increased to 107.4 million families, and estimated 535

million people, equivalent to ~40% of Indian population [22,27]. The key

health sector specific announcements in the union budget 2018-19 are

listed in Box 2. The key components and implementation

design of both HWCs and AB-NHPM/PM-RSSM are publically available and

summarized in Web Table I and

Web Fig. 1-3

[5,22,26,27]. The additional details on team at HWCs and on the

design structure of AB-NHPM/PM-RSSM are summarized in

Web Appendix

1 and 2, respectively [1,5, 22,26,27].

|

Box 2 Health in Union Budget 2018-19 of

India [22, 27]

• Ayushman Bharat Program received an

allocation of Rs 3,200 Crore (US$ 500 Million). This is for

union government share and state contributes remaining as per

agreed formula; therefore, total allocation would be in range of

Rs 5,000 Crore (US$ 770 Million) from state and union

government, combined.

• Cash assistance of Rs 500 (US$ 8) per

months for Tuberculosis patient for the duration of treatment

and this initiative has been allocated Rs 600 Crore (US$ 90

million).

• Twenty-four district hospitals to be

upgraded to medical colleges, to ensure at least 1 medical

college for every 3 parliamentary constituencies and at least 1

government medical college in each state of India.

• The existing 3% ‘education cess’ has been

changed to 4% ‘Health and education cess’. This would generate

additional revenue of Rs 11,000 crore (US$ 1.7 billion) during

the financial year.

• Initiative to control air pollution by

supporting the farmers in Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and

National Capital region of Delhi for the in-situ disposal

of crop waste.

• Expansion of Ujjwala scheme (to provide

free ‘Liquefied Petroleum Gas’ connection to rural women) from

50 million to 80 million women in India. Allocation of Rs. 3,200

Crore (US$ 490 million).

• Continuation of Swachch Bharat Mission

(SBM) with target of building addition 20 million toilets.

Allocation to National Nutrition Mission has been doubled to Rs.

3,000 Crore (US$ 460 million).

• Increase of nearly 10% for Pradhan Mantri

Jan Aushadhi Yojana, Swachch Bharat Mission Rural and for

Anganwadi Services.

• The government’s proposal to private sector

and corporates to support the process of establishing HWCs could

be considered a far-reaching policy shift to engage and invite

private sector in strengthening primary healthcare in India.

• The social welfare surcharge of 10% to fund

social schemes and merger of three public sector insurance

companies would indirectly affect this program and health

sector.

• Higher Education Finance Agency (HEFA) to

be restructured to fund infrastructure and research in medical

institution as well. HEFA was announced in union budget 2017-18.

|

Prioritizing health and acknowledging linkage with

wealth

The union budget 2018-19 of India can be credited as

one of the most explicit political acknowledgement of linkage between

‘good health’ and ‘economic growth’. The Union Finance Minister in his

budget speech said: "Only ‘Swasth Bharat’ can be ‘Samridha Bharat’.

India cannot realize its demographic dividends without its citizen being

healthy.’ and ‘Ayushman Bharat Program will build a New India

2022 and ensure enhanced productivity, well-being and avert wage loss

and impoverishment. These Schemes will also generate lakhs of jobs,

particularly for women" [22]. Soon after union budget, the

health needs of the people of India occupied center stage of discussion,

by political leaders, media and people, and terms such as ‘universal

health coverage’ and ‘Ayushman Bharat Program’ were introduced in

the functional dictionary of general public [25,30,31] – something,

which has a potential to place health higher in future public and

political discourses in India.

In a shift, AB-NHPM has the beneficiaries beyond

traditional approach of targeting ‘below poverty line’ (BPL) population.

Inclusion of ‘vulnerable and deprived population’ identified through

Socioeconomic and Caste Census (SECC) will nearly double the number of

people to be benefited [22,27,32]. The benefits of HWCs, when fully

functional, would be available to 100% of population of the country.

Discussion

This was the first union budget of India since the

release of NHP-2017 in March 2017. This budget follows upon a few

strategies proposed in the NHP-2017, including suggestions to invest

two-third or more of government funding on the health on primary

healthcare, establishing health and wellness centers and introducing

‘strategic purchasing’ in healthcare, among other [1,22].

The ABP combines two initiatives, announced in past

as a single program. The NHPS was first announced in union budget of

2016-17, though with a coverage of Rs. 100,000 (US$ 1550) per family per

annum [23,24] and the HWCs were proposed by the task force on

strengthening primary healthcare in India in 2016 and first announced in

the union budget 2017-18 [5,23]. The ABP has strengths and limitations (Table

II), and potential to address select but key health challenges in

the country. Two initiatives in ABP together will meet the range of

healthcare needs across primary, secondary and tertiary care, appears

synergistic, and may help in increasing accessibility, availability,

appropriate care and affordability. This can help India progress towards

UHC.

|

TABLE II Ayushman Bharat program: SWOT

Analysis

|

|

Strengths

- Apparent shift from ‘disease specific’ and

‘Reproductive and child health’ focus of government initiatives

to comprehensive Primary healthcare

- Shift in targeting of social sector program

from ‘poor only’ to expanded approach of vulnerable and deprived

population (increased target beneficiaries significantly)

- Seemingly high level of political

commitment

- Acknowledgement of linkage between better

health and economic growth of India

Opportunities

- Alignment with the NHP 2017 and NITI

Aayog’s three year Action Agenda 2017-20.

- Wide public and media attention on the

program can bring desired public accountability to expedite

implementation

- Implementation experience from RSBY and

other schemes such as free medicines could be utilized for rapid

scale up

- Global and national level focus on

universal health coverage

- Upcoming general elections and assembly

elections in a number of states.

- Potential to develop innovative models and

strategies for strengthening entire healthcare system in India.

SWOT: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats

|

Weaknesses

- HWCs are only a part of primary healthcare

system, requires broader strengthening of entire health system

- Limited attention and focus on reform of

broader health system

- Out-patient department visits, which

constitute a large part of out of pocket expenditure, not part

of PM-RSSM.

Threats

- Change in the political leadership or the

priorities of the elected governments (before or after

elections)

- Limited buy-in and interest by the Indian

states in PM-RSSM (both political and other reasons)

- Challenge in availability of mid-level care

providers for Health and Wellness centres could delay the

setting up of 150,000 HWCs

- Focus on these components only and the

other broader health system needs ignored.

- Disproportionate focus on one of two initiatives in ABP

|

The ABP as a program could be termed bold and

ambitious for both the initiatives. The financial coverage in AB-NHPM is

around 17-times more generous than RSBY, and two- to four-times more

generous when compared with the other states’ government-funded health

insurance schemes in India. NHPS/PM-RSSM targets almost twice the target

beneficiaries and thrice of actual numbers enrolled under RSBY in year

2016-17. Understandably, NHPS has received a lot of attention in India

and across the developing part of the world. However, arguably, the

proposal to set up 150,000 HWCs by 2022 is even bigger and potentially

more impactful initiative for the reasons listed here. One, the

comprehensive primary healthcare delivered through HWCs would benefit

entire 1.3 billion people of India across rural and urban setting.

Second, it would strengthen government primary healthcare system, which

caters to only 10% health needs of the people at present while a

well-functioning primary healthcare system has potential to cater up to

80-90% of health needs [33,34]. Third, strengthening primary healthcare

through HWCs can bring efficiency in health services through increased

access, gate keeping and a functional two-way referral system. Fourth

and importantly, the extended services in HWCs would cover a number of

non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and can tackle the epidemiological

transition. In 2016, the NCDs contributed to nearly two-third of all

mortality and 56% of preventable mortality in India [17].

There is sufficient evidence available that

strengthening of primary healthcare is the most appropriate approach to

achieve UHC. Investment on comprehensive primary healthcare system is a

practical and affordable solution for India [1]. Health services are

human resource intensive, and India has plenty of potentially trainable

human resources available at a low cost. The successful engagement of

nearly 1 million Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) under

National Health Mission (NHM) in India is a proof of the potential and

effectiveness of community health workers [35,36]. More of appropriately

skilled workforce such as mid-level healthcare providers (MLHP) as part

of HWCs would be affordable, efficient and effective. In the process,

India might end up building a low cost, high impact model of primary

healthcare, for rest of the world. Many countries such as Chile, Costa

Rica and Thailand have succeeded through their own context-specific

model for primary healthcare at low cost, and achieved comparable health

outcomes as to high-income countries.

The global evidence on effectiveness of government

funded and social health insurance (SHI) in reducing OOPE is limited,

either side [37,38]. However, there is enough evidence to conclude that

if implemented well and at-scale, insurance schemes increase access to

health services, can save lives, and improve financial affordability. It

is this emerging evidence and intention to make health services

affordable to poor people, that many state governments in India launched

publically funded health insurance schemes, mostly in the last decade (Table

III). There is evidence that such schemes can prove an effective

tool to improved quality of health services through differentiated rates

and incentives if providers meet certain quality standards, and have

accreditation; increased adherence to Standard Treatment Guidelines

(STGs), and provider’s willingness to accept slightly higher regulation,

amongst other approaches [39-41].

TABLE III Evolution of Health Insurance Schemes at National and State Levels in India

|

Year (of start/ launch) |

Name of the scheme

|

Scope

(National or state specific) |

|

1948 |

Employees’ State Insurance Scheme |

National |

|

1954 |

Central Government Health Scheme |

National |

|

1986 |

Private Insurance- Mediclaim |

National |

|

2003 |

Ex Servicemen Contributory Health Scheme |

National |

|

2003 |

Universal Health Insurance scheme (UHIS) |

National |

|

2003 |

Yeshasvini Cooperative Farmers Health Insurance, Vajpayee

Arogyashree Scheme (2010) , |

Karnataka |

|

Rajiv Arogya Bhagya (2013) |

|

|

2005 |

Health Insurance Scheme for handloom weavers |

National |

|

2006 |

Shilpi Swasthya Yojana for handicrafts artisan |

National |

|

2007 |

Aarogyasri scheme (continued as Dr NTR Vaidya Seva (2015)

Aarogya Raksha scheme, 2017 |

Andhra Pradesh

|

|

2007 |

Aarogyasri Health Scheme (Continuation in 2015) |

Telangana |

|

2008 |

Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) |

National

|

|

2008 |

Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme (CHIS) and CHIS Plus |

Kerala |

|

2008 |

Mizoram State Health Care Scheme |

Mizoram |

|

2009 |

Niramaya Health insurance schemeContinued as Swablamban Health

insurance schemes in 2016 |

National

|

|

2010 |

Rajiv Gandhi Jeevandayee Aarogya Yojana, Mahatma Jyotiba Phule

Jan Aarogya Yojana (2017) |

Maharashtra |

|

2012 |

Mukhya Mantri Amrutam YojanaMukhya Mantri Amtritam Vatsalya

(2014) |

Gujarat |

|

2012 |

Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme |

Tamil Nadu |

|

2012 |

Megha Health Insurance Scheme, |

Meghalaya |

|

2012 |

Mukhyamantri Swasthya Bima Yojana |

Chhattisgarh |

|

2013 |

Biju Krushak Kalyan Yojana, |

Odisha

|

|

2013 |

Sanjeevani Swasthya Bima Yojana |

Dadra and Nagar Haveli, and Daman and Diu |

|

2014 |

The Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister’s Universal Health

Insurance Scheme |

Arunachal Pradesh |

|

2015 |

Andaman and Nicobar Island Scheme for Health Insurance |

Andaman and Nicobar Island |

|

2015 |

Bhagat Puran Singh Health Insurance Scheme,Bhai Ghanhya Sehat

Sewa Scheme (BGSSS) |

Punjab |

|

2015 |

Bhamashah Health Insurance Scheme |

Rajasthan |

|

2016 |

Din Dayal Swasthya Seva Yojana

|

Goa |

|

2016 |

Senior Citizen Health Insurance Scheme (SCHIS) within RSBY |

National |

|

2016 |

Mukhya Mantri State Health Care Scheme (MMSHC) |

Himachal Pradesh

|

|

2016 |

Puducherry Medical Relief Society

|

Puducherry

|

|

2016 |

Mukhyamantri Swasthya Bima Yojana |

Uttarakhand |

|

2016 |

Atal Amrit Abhiyan |

Assam |

|

2016 |

Swasthya Sathi |

West Bengal |

|

2018 |

NHPS/AB- NHPM/PM-RSSM |

National |

|

This is an indicative list. For every state,

the year of start of first health insurance schemes has been

listed. A number of these schemes are for specific target

population groups. A number of Indian states have more than one

scheme; however, only a few key schemes are listed. There are a

few Indian states, with no insurance scheme. Most of the states

in India, in addition, have schemes with provision of

re-imbursement for medical expenses for selected health

condition and those schemes are not listed.

|

The insurance schemes in India have had low

population coverage (against the target beneficiaries) and limited

impact on OOPE. The coverage with insurance schemes in surveys have

ranged from 11-12% families in India [42] or that at least one member in

around 28% of Indian families [43]. Considering most of the insurance

schemes cover a narrow range of secondary- and tertiary-care procedures,

and exclude outpatient services; there seems to be a long way in

reducing OOPE in India. The cost of consultations in outpatient

department, along with cost of medicines and diagnostics are the major

contributor to the OOPE in India, which were not covered in either RSBY

earlier or PM-RSSM now. Understandably, health insurance schemes,

focused only on secondary and tertiary level hospitalization, do not

always lead to reduced OOPE. Rather in some cases, OOPE increases as the

awareness about schemes can lead to utilization of health services (by

the people who were not accessing services) and people have to pay for

additional services not covered [38,39,44]. The budgetary allocation to

RSBY during the years of implementation was less than one percent of

total annual government spending on health in India. Clearly, the impact

on OOPE could not have been much different. In the similar vein,

considering that total OOPE in India in 2014-15 was Rs 302,425 Crore

(Approx. US$ 46.5 billion) and a scheme such as PM-RSSM with an annual

budget of around Rs 12,000 Crore (or US$ 1.8 billion), even with full

scale implementation would have only marginal impact on reducing OOPE.

Though, it may prevent catastrophic health expenditures for the families

covered.

For health insurance schemes being effective and

efficient, a common and bigger pool, administered through a single

agency is considered the best approach. India has multiple schemes with

their independent and almost parallel administration, management and

beneficiaries. Even within a state, there are multiple scheme running

parallel, targeted at different beneficiaries. If PM-RSSM can initiate

the process of merger of multiple schemes in a single pool over period

of time and where non-poor join by paying the premium, that would make

it truly a ‘game changer’. In this context, the initiative by the

government of Karnataka to combine 7 ongoing and existing schemes in a

single pool, to be administered by a common agency, could be studied for

probable learnings [45]. At national level, a few schemes for financial

assistance to patients have been harmonized by union government by the

abolition of autonomous bodies and transfer to Ministry of Health &

Family Welfare [46]. Alongside, a road-map for the extension of benefit

of PM-RSSM to additional population, with graded subsidy, should be

actively considered and strategy outlined.

Many countries have included health as a basic right

in their constitution [47]. Evidence indicates that inclusion of health

as basic right help in increasing access to services and holding the

governments accountable. While India has adopted a number of right based

initiatives, including the ‘right to education’ legislation, the health

has not been mentioned as a right in the constitution of India, though

often interpreted in context of Article 21 on right to life [48].

India’s NHP-2017 takes a stride and proposes ‘progressively incremental

assurance’ towards health, though it falls short of ‘right to health’

[1]. The sustainability of select SHI in India over other schemes has

partially been attributed to legislative provisions [49]. A scheme of

magnitude of PM-RSSM might benefit from legislative backing as has been

case with Employee State Health Insurance Scheme (ESIS) and Central

Government Health Schemes (CGHS) [50, 51].

The National Health Services (NHS) of United Kingdom

is said have emerged from political commitment in aftermath of

post-World War II [52]. With ABP in India, there appears a political

will and commitment. The community and civil society plays a crucial

role in ensuring that political promises and commitments sustained in

changing political environment [52,53]. An institutional and legally

backed-up mechanism to engage communities and civil societies, such as

national health assembly in Thailand [54] may help India as well, though

the modus operandi could be home-grown.

In implementation of HWCs, caution has to be

exercised and an overzealous attempt to expand package of services

should not results in reduced attention on maternal and child health

(MCH) services. Rather, the MCH service platform should be used to build

upon expanded package of services. In addition, HWCs and financial

affordability offered through PM-RSSM would further increase

accessibility, affordability to all populations including mothers and

children and bring hitherto uncovered populations to the public health

system. HWCs can help in addressing different types of inequities in

health services, as identified by multiple surveys. There is evidence

that when geographical and financial access to services is increased, it

is poor and women who are more commonly benefited.

The people have to be at the center of health

services and in scale-up and reform of health services, attention should

not be on supply-side interventions only; people’s perspective should

get due consideration. Mechanisms for satisfaction survey and feedback

assessment should be strengthened, and the data used for regular actions

and initiatives.

Finally, there is a strong economic case for

accelerated implementation of ABP in India. Healthier population means

enhanced overall productivity, reduced wage loss and less

impoverishment. In Germany, domestic health economy contributes to 12%

of gross value added and 8% of Germany’s export [55]. The rapid

implementation of ABP in India has potential to generate employment

through recruitment of additional workforce such as MLHPs.

Implementation challenges in ABP and possible

solutions

The initiative under ABP can be called ambitious and

bold; however, would be operationally challenging for a health system,

not known to deliver. The sub-optimal implementation and partial

scale-up has been the case with a number of initiatives in the past

[27,56-60]. This includes initiatives started a few years ago (i.e.,

a number of free treatment and diagnostics schemes by union and state

governments) as well as NHPS announced in 2016 and the proposed

universalization of maternity benefit scheme, announced in December 2016

[61,62]. Clearly, in health sector, more need to be done for translating

policies and intentions into practice.

Health sector is a specialized field where successful

outcome requires getting both design and implementation right. In

setting up HWCs, a ‘rate limiting factor’ could be recruiting MLHPs or

Community Health Officer (CHO), one each would be required for 150,000

HWCs. This is an opportunity to innovate and explore solutions for

recruitment of additional cadre of providers on priority basis.

Alongside, the quality of services delivered through these facilities

needs to be assured by achieving Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS).

There is limited capacity amongst Indian states in

identification and enrolment of beneficiaries, designing the benefit

package, fixing the package rate, empanelment of facilities, monitoring

and regulation and fraud detection. Many of these are ‘sine qua non’ for

success of a health insurance scheme. The insurance schemes require a

state level authority with sufficiently trained staff, and a

well-functioning Information technology (IT) system to implement the

program. In India, the capacity of the states to run insurance schemes

is lowest where these are needed most. The success of PM-RSSM would also

be dependent upon how the supply-deficient Indian states such as Uttar

Pradesh, Bihar and the North-eastern states take up and implement the

scheme. A well-functioning IT platform would be essential to meet

diverse needs of different stakeholders including patients, service

providers and program managers [26,27]. The significance of IT

platform cannot be over-emphasized and it would be very crucial in

strategic purchase of services, provider payments, fraud detection and

monitoring of the scheme. India to utilize the opportunity provided by

PM-RSSM to build a strong IT platform not only for this scheme but also

to develop an integrated health information platform to bring multiple

IT systems on a single platform. The implementation would benefit from

generating real time data and then use of data for action. As a first

step, the data generated from RSBY should be analyzed and learnings used

for designing and scaling-up of PM-RSSM.

The ABP success on advancing health and achieving UHC

in India would be dependent upon the response and leadership of Indian

state. The states may require different model and design to address both

supply deficiency and capacity. A few additional suggestions to improve

implementation effectiveness of ABP are provided in Box 3.

|

Box 3 Actionable Steps for Improving

Implementation Effectiveness of Ayushman Bharat Program

For HWCs

• Conduct detailed costing exercise, agree on

roadmap, and allocate commensurate financial resources.

• Aggressive scale-up and not incremental

approach.

• Give attention to urban primary healthcare

and think of additional and innovative approaches with capital

investment in urban areas.

• Establish autonomous authority/corporations

to provide technical support for setting up HWCs.

• Information technology back-bone, and other

areas for intervention.

For AB-NHPM/ PM-RSSM

• Make insurance scheme easy to use for

people so that poor are able to use the services.

• Communicate the benefit plan and scheme to

target beneficiaries to ensure enrolment.

• A national level IT platform, to facilitate

beneficiary identification, portability, the payment and detect

fraud.

• Linkage of out-patient care with

specialized care to ensure efficiency and effectiveness in

health services.

• Strengthening of supply side is as important as demand

based financing schemes.

|

The way forward to strengthen health systems in India

As health seems to have received priority in India,

the opportunity should be used as a catalyst for decisive and broader

health system re-designing and strengthening. A few steps can contribute

to the implementation effectiveness:

1. Retain focus on increasing government

investment on health: In the years ahead, the universal

implementation of two components of ‘Ayushman Bharat Program’ would

require approx. Rs. 70-100 thousand Crore (US$ 11.5 - 15.5 billion)

per annum [63]. This increased investment in health would be in

alignment with NHP-2017 target of government spending 2.5% of GDP on

health by year 2025 [1]. This would require an annual increase of

20-25% in budgetary allocation by both national and state

governments. Not allocating enough funds to already underfunded

health sector, and only promise of providing funds as per the need,

can be taken as ‘perverse incentive’ by fiscally deficit governments

as a reason not to ramp-up implemen-tation. Measuring the government

investment on health as percentage of GDP is a better approach than

comparison by the nominal values or budget to budget estimates. The

ABP should not result in reduced attention from the targets of

NHP-2017. The UHC is about everyone, everywhere [64], and the

mechanisms for financial protection beyond targeted 40% families as

in PM-RSSM, should be explored and linkage between primary and

secondary/tertiary care strengthened. This should be part of

mid-term roadmap and ‘progressive universalization’ of financial

protection in India. Over the period of time, non-poor should be a

part of a government scheme. While premium for poor can be borne by

government, the non-poor can subscribe to an insurance scheme

(preferably, mandatory contribution).

2. Strengthen and scale up ongoing initiatives:

Strengthening a number of ongoing initiatives, i.e., free

medicines and diagnostics schemes, scaling up services in urban

areas, expansion of services for non-communicable diseases and

strengthening of the referral linkages at all levels of facilities,

are complementary and should continue to receive attention. Health

outcomes in selected urban areas are often worse than rural areas

and urban population faces additional challenges such as limited

public space for physical activities, air pollution, over-crowding

and migratory populations, which pose additional health risks

[59,65]. In urban set-up, converting the existing urban PHCs into

HWCs would not be enough and capital investment to expand PHC

infrastructure is also needed. A PHC and government medical officer

for every 50,000 population would not be able to cater the health

needs of urban population. An UPHC should be available for every

10-20,000 population. The initiatives such as ‘Mohalla Clinics and ‘Basthi

Devakhana’ should be actively considered for expansion in other

urban settings of India [66,67].

3. Establish institutional mechanism to bring

stakeholders together: Engagement with the community and

civil society organization will play a crucial role. This can bring

accountability and ensure continuity, rapid scale-up of the

initiatives, and can place health in electoral agenda. The academic

and research institutions as knowledge partners can help in

designing local solutions, while continue to derive learnings from

international experience and good practices in due course. The

success of ABP would also be dependent upon how best the proposed

initiatives in ABP are anchored on other flagship initiatives and

priority programs of government, such as Aspirational District

Program (ADP) and Gram Swaraj Abhiyan (GSA), launched around same

time [68,69]. In India, while there are a few mechanisms, i.e.,

Central Council of Health and Family Welfare, for limited

stakeholder of non governmental stakeholders. However, there is need

for more inclusive, dedicated and sustained institutional approach

are possible learnings from experience of national health assemblies

in Thailand [54].

4. State Government to take lead for advancing

UHC and explore the legal framework for PM-RSSM Achieving UHC in

India can be supported by examination of existing legislative

provisions and exploring additional ones to achieve stated policy

intentions. Sustainability and long-term continuity of social health

insurance schemes in India has been partially attributed to

legislative back up [48-51]. Similarly, hospitals and public health

is a state responsibility as per constitution of India. Therefore,

uptake of ABP is a lot dependent upon interest and leadership of

Indian states. In the long run, it might be helpful to explore the

pros and cons of bringing health in concurrent list of constitution

of India.

5. Use ABP as platform to bigger health system

reforms in India: The success of ABP would be in bringing

the shift from the traditional approach of disease specific and

targeted initiatives to focus on people-centered integrated services

and financial protection. One of the strengths and success factors

of National Health Mission (NHM) in India was attempt to strengthen

health system. The health system strengthening does not appear to be

an explicit focus in ABP in India. In due course, it would be

beneficial to converge the ABP and NHM to improve both supply- and

demand-side issues and achieve a stronger health system in all

states of country.

Conclusion

India has committed to achieve UHC as a signatory to

the globally agreed Sustainable Development Goals as well as through the

NHP 2017. For countries aiming to march towards UHC, there is no ‘one

size fit all’ solution, and the strategies have to be locally developed

and implemented. Every strategy/program would have to build upon

strengths and attempt to minimize limitations. Ayushman Bharat Program

appears to be a balanced approach, which combines provision of

comprehensive primary healthcare (through HWCs) and secondary and

tertiary care hospitalization (through PM-RSSM). While ABP would help

India make progress towards UHC, this program alone would not be enough

and needs to be supplemented by rapid scale-up and convergence of

ongoing schemes and programs, and taking a few additional measures. The

ABP can prove an initiative bigger than simply delivering health

services and rather a platform to prepare India for making health

coverage universal.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

Disclaimer: Author is a staff member of World

Health Organization. The views and opinion expressed in this article are

personal and should and cannot be attributed to WHO or any other

organizations he has been affiliated in past or at present.

References

1. Government of India. National Health Policy 2017.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi, 2017. p.

1-32.

2. World Health Organization. World Health Report

2010: Health Financing for Universal Coverage. Geneva: WHO, 2010.

3. [No author listed]. Health in India, 2017. Lancet.

2017;389:127.

4. Shiva Kumar AK, Chen LC, Choudhury M, Ganju S,

Mahajan V, Sinha A, et al. Financing health care for all:

challenges and opportunities. Lancet. 2011; 377:668-79.

5. Government of India. Report of the Task force on

Primary Health Care in India. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,

Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi, 2017. p. 1-60.

6. Gupta I. Out of Pocket Expenditure and Poverty:

Estimates from 61 Rounds of NSS. Expert Group on Poverty. Planning

Commission, New Delhi; 2009. Available from:

http://planningcommission.gov.in/reports/genrep/indrani.pdf.

Accessed February 15, 2018.

7. World Health Organization and International Bank

for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. Tracking Universal

Health Coverage: 2017 Global Monito-ring Report. Available from:

http://www.who.int/health info/universal_health_coverage/report/2017_global_

monitoring_report.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

8. Government of India. Rural Health Statistics 2017.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi, 2017.

9. Government of India. Rural Health Statistics 2016.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi, 2016.

10. Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. National

Health Profile 2017. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman

Bhawan, New Delhi, 2017. p. 1-270.

11. National Health Systems Resource Centre. National

Health Accounts 2014-15. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman

Bhawan, New Delhi, 2017. p 1-74.

12. World Health Organization. World Health

Statistics 2017: Geneva: WHO. 2017. Available from:

http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2017/en/.

Accessed Febuary 04, 2018.

13. National Sample Survey Organization. Report of

71st round of National Sample Survey 2014. Ministry of Planning,

statistic and implementation, New Delhi, 2017. Available from:

http://mospiold.nic.in/national_data_ bank/ndb-rpts-71.htm. Accessed

February 10, 2018.

14. Planning Commission, Government of India. Twelfth

Five Year Plan of India: Health Chapter. New Delhi, 2017. p. 1-60.

15. Das J, Holla A, Das V, Mohanan M, Tabak D, Chan

B. In urban and rural India, a standardized patient study showed low

levels of provider training and huge quality gaps. Health Aff

(Millwood). 2012;31:2774-84.

16. Government of India. The Clinical Establishment

(registration and regulation) Act, 2010. Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi. 2010.

17. Indian Council of Medical Research and Public

Health Foundation of India. State of Health in India, Nov 2017. Ministry

of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi, 2017, p:1-32.

18. 2015 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators.

Healthcare Access and Quality Index based on mortality from causes

amenable to personal health care in 195 countries and territories,

1990-2015: A novel analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study

2015. Lancet. 2017;390:231-66.

19. Government of India. Millennium development

Goals, India Country Report 2015. Minsitry of Statistics, Planning and

Implementation. Govt of India, New Delhi. 2016. Available from:

http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/mdg_2july15_1.pdf.

Accessed March 03, 2018.

20. Deshmukh V, Lahariya C, Krishnamurthy S, Das MK,

Pandey RM, Arora NK. Taken to health care provider or not, under-five

children die of preventable causes: findings from cross-sectional survey

and social autopsy in rural India. Indian J Community Med.

2016;41:108-19.

21. Lahariya C, Dhawan J, Pandey RM, Chaturvedi S,

Deshmukh V, Dasgupta R, et al.; for INCLEN Program Evaluation

Network. Inter district variations in child health status and health

services delivery: lessons for health sector priority setting and

planning from a cross-sectional survey in rural India. Natl Med J India.

2012;25:137-41.

22. Government of India. India Budget 2018-19 and

Budget Speech. Ministry of Finance, New Delhi. Available from:

http://www.indiabudget.gov.in/. Accessed Febuary 12, 2018.

23. Government of India. Union Budget website for

previous years. Ministry of Finance, New Delhi. Available from:

http://www.indiabudget.gov.in/. Accessed February 12, 2018.

24. Lahariya C. Budget India 2008: What is new for

health sector. Indian Pediatr. 2008; 45:399-400.

25. BBC News. India unveils ‘world’s largest’ public

healthcare scheme. 1 February 2018. Available from:

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-42899402. Accessed February

15, 2018.

26. Government of India. National Consultation on

Ayushman Bharat: Operationalizing Health and Wellness Centres to deliver

Comprehensive Primary Health Care. 1-2 May 2018; New Delhi.

27. Press Information Bureau. Cabinet approves

Ayushman Bharat – National Health Protection Mission. 21 March 2018; New

Delhi. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=177816.

Accessed February 15, 2018

28. Government of India. Rashtiya Swasthya Bima

Yojana. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi.

2014.

29. Highlights of union budget 2016-17. The Hindu,

New Delhi; 29 March 2016.

30. NITI Aayog comes to the Rescue as Health Ministry

Clueless on ‘World’s Largest Healthcare Programme. The Wire, 2018, Feb

03. New Delhi. Available from: https://thewire.in/220634/health-budget-2018-niti-aayog/.

Accessed February 15, 2018.

31. Through the looking glasses: The Readers’ Editor

writes: Scroll.in should take the lead in advocating primary healthcare

overhaul. Scroll; New Delhi;2018, Feb 26. Available from: https://scroll.in/article/869658/the-readers-editor-writes-scroll-in-should-take-lead-in-advocating-a-primary-healthcare-overhaul.

Accessed February 27, 2018.

32. Government of India. Socioeconomic and Caste

Census (SECC). Registrar General of Census Operations, New Delhi. 2012.

33. World Bank. Investing in Health: World

Development Report 1993. New York: Oxford University Press,1993.

34. Save the children. Primary Healthcare first.

London: Save The children Fund 2017; p. 1-4. Available from:

https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-practice/our-featured-reports/primary-health-care-first

Accessed February 12, 2018.

35. Press Information Bureau. Evaluation of

Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA). Government of India, 2015.

Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease. aspx?relid=116029.

Accessed February 12, 2018.

36. Government of India. National Health Mission.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi. 2005.

37. Karan A, Yip W, Mahal A. Extending health

insurance to the poor in India: An impact evaluation of Rashtriya

Swasthya Bima Yojana on out of pocket spending for healthcare. Soc Sci

Med. 2017;181:83-92.

38. Ghosh S, Gupta ND. Targeting and Effects of

Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on Access to Care and Financial

Protection. Econ Pol Weekly. 2017;52:32-40.

39. Sood N, Bendavid E, Mukherji A, Wagner Z, Nagpal

S, Mullen P. Government health insurance for people below poverty line

in India: Quasi-experimental evaluation of insurance and health

outcomes. BMJ. 2014;349:g5114.

40. Is National Health Protection scheme good public

policy? Mint (newspaper); New Delhi; March 12, 2018; p.12.

41. Morton M, Nagpal S, Sadanandan R, Bauhoff S.

India’s largest hospital insurance program faces challenges in using

claims data to measure quality. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:1792-9.

42. Salve P, Yadavar S. Why India’s National Health

Insurance Scheme Has Failed Its Poor. India Spend, Mumbai; 17 October

2017. Available from:

http://www.indiaspend.com/cover-story/why-indias-national-health-insurance-scheme-has-failed-its-poor-49124.

Accessed February 15, 2018.

43. International Institute of Population Sciences.

National Family Health Survey - 4. National report. IIPS, Mumbai and ORC

Macro, 2017.

44. National Health Protection Scheme will not help

its intended beneficiaries. Mint; 2018, Feb 15; New Delhi. Available

from:

http://www.livemint.com/Opinion/k80NvWWKvFGwHptVIDIqNJ/National-Health-Protection-Scheme-will-not-help-its-intended.html.

Accessed February 15, 2018.

45. Karnataka to roll out Aadhaar-linked universal

health coverage on November 1. The New Indian Express; Bengaluru; 28

August 2017.

46. Press Information Bureau. Cabinet approves

rationalization of Autonomous Bodies under Department of Health & Family

Welfare. Government of India; New Delhi; 7 February 2018. Available

from: http://pib.nic.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1519860.

Accessed February 12, 2018.

47. Kurian OC. Financing public healthcare in India:

towards a common goal. Oxfam India: New Delhi, 2015. P. 1-18.

48. Reddy KS, Patel V, Jha P, Paul VK, Kumar AK,

Dandona L; Lancet India Group for Universal Healthcare. Towards

achievement of universal health care in India by 2020: A call to action.

Lancet. 2011;377:760-8.

49. Kaur H. Why Modi Must Seek Legal Backing for His

Ambitious Healthcare Project. Swarajya magazine; 27 April 2018.

Available from: Available from:

https://swarajyamag.com/ideas/what-are-the-arguments-for-having-a-modicare-law.

Accessed February 12, 2018.

50. Government of India. Employee State Health

Insurances Act, 1948.

51. Government of India. Central Government health

Insurance scheme, 1954

52. Webster C. The National Health Services: a

political history. Second edition. Oxford University Press. Oxford;

2002.

53. Hughes D, Leethongdee S. Universal coverage in

the land of smiles: Lessons from Thailand’s 30 Baht health reforms.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:999-1008.

54. Rasanathan K, Posayanonda T, Birmingham M,

Tangcharoensathien V. Innovation and participation for healthy public

policy: the first National Health Assembly in Thailand. Health

Expectations. 2012;15:87-96.

55. Kickbusch I, Franz C, Holzscheiter A, Hunger I,

Jahn A, Köhler C, et al. Germany’s expanding role in global

health. Lancet. 2017;390:898-912.

56. Press Information Bureau. Universal Health

Insurance Scheme (2003). PIB, Government of India. New Delhi. 2011.

Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/Print Release.aspx?relid=78863.

Accessed February 12, 2018.

57. National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

Report on Utilisation, Fund Flows and Public Financial Management under

the National Health Mission: A Study of Selected States, NIPFP; 2017.

58. Kapur A. Baisnab P. Budget brief: National health

Mission; Government of India, 2018-19. Accountability Initiative; Center

for Policy research, New Delhi. p. 1-8. Available from: http://accountabilityindia.in/budget/briefs/download/1814.

59. Lahariya C, Bhagwat S, Saksena P, Samuel R.

Strengthening urban health for advancing universal health coverage in

India. J Health Management. 2016;18:361-6.

60. Press Information Bureau. A new health protection

scheme to provide health cover up to Rs.1 lakh per family announced.

PIB, Government of India. New Delhi. Press release on 29 Feb 2016.

Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=136989.

Accessed February 15, 2018.

61. Press Information Bureau. Cabinet approves pan-india

implementation of maternity benefit program. PIB, New Delhi, 17 March

2017. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=161857.

Accessed February 15, 2018.

62. Press Trust of India. Maternity benefit scheme

unlikely to get boost in Budget 2018. Times of India; New Delhi; 30 Jan

2018. Available from: https://timesofindia. indiatimes.com/business/india-business/maternity-benefit-scheme-unlikely-to-get-boost-in-budget-2018/articleshow/62712742.cms

Accessed February 15, 2018.

63. Lahariya C. Strengthening primary healthcare:

From promises to reality. Ideas for India; 27 March 2018. Available

from:

http://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/human-development/strengthening-primary-healthcare-from-promises-to-reality.html

. Accessed February 12, 2018.

64. World Health Organization. World Health Day 2018:

Universal health coverage: everyone, everywhere. Geneva: WHO; 2018.

Available from: http://www.who.int/campaigns/world-health-day/en/.

Accessed February 18, 2018.

65. Government of India. National Urban Health

Mission (NUHM): Framework for Implementation. Ministry of Health and

Family Welfare, Nirman Bhawan, New Delhi. 2013.

66. Lahariya C. Mohalla Clinics of Delhi, India:

Could these become platform to strengthen primary healthcare? J Family

Med Prim Care. 2017;6:1-10.

67. Lahariya C. Decongest hospitals with Mohalla

clinics. Deccan Herald; Bengaluru; 27 May 2017; Available from:

https://www.deccanherald.com/content/613762/decongest

-hospitals-mohalla-clinics.html. Accessed February 12, 2018.

68. Press Information Bureau. Transforming 115

backward districts across the country. Government of India. 23 Nov 2017;

New Delhi. Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=173788.

Accessed February 12, 2018.

69. Press Information Bureau. Gram Swaraj Abhiyan

on Ambedkar Jayanti. Government of India. 6 April 2018; New Delhi.

Available from: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=178495.

Accessed February 12, 2018.