December, 2015. The

invited experts included Pediatricians, Developmental Pediatricians,

Pediatric Neurologists, Psychiatrists, Remedial Educators and Clinical

Psychologists. The participants framed guidelines after extensive

discussions and review of literature. Thereafter, a committee was

established to review the points discussed in the meeting, and the

points of consensus on evaluation and management of ADHD are presented

herein.

Recommendations

ADHD is a disorder that manifests in early childhood.

The symptoms affect cognitive, academic, behavioral, emotional and

social functioning. ADHD is a chronic condition and children and

adolescents with ADHD are to be considered as children and youth with

special health care needs [5].

ADHD has a genetic and biochemical basis. Role of

environmental factors is uncertain; they may influence symptoms of ADHD

(sub-syndromic) rather than the syndrome of ADHD [5].

Developmental Screening

Parent and teacher-rated scales are recommended for

screening, which have been used globally as well as in studies conducted

in India to screen ADHD, followed by a formal diagnosis using the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). These

scales include the Conners Index Questionnaire, and the Vanderbilt ADHD

Diagnostic Teacher Rating Scale [6,7].

Core clinical features: Clinical sub-types

include: predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, predominantly inattentive

and combined ADHD.

Hyperactivity-Impulsivity (HI): Although

typically observed by 4 years of age, HI is increasingly being reported

in children with younger age of presentation of symptoms. HI increases

during the subsequent three to four years, peaks at seven to eight years

of age and declines thereafter. By adolescence, it is difficult to

identify HI, although the adolescent may feel restless or have

difficulties in settling down.

In contrast, impulsivity usually persists throughout

life and it is influenced by the child’s environment. Adolescents with

untreated ADHD and easy access to alcohol and substances of abuse are at

greater risk of substance abuse, than adolescents without ADHD [8].

Inattention: Children with predominantly

inattentive ADHD have limited ability to focus and they are slow in

cognitive processing and responding. Note that these symptoms are not

due to defiance or lack of comprehension [9]. Inattention is usually

identified late and not apparent until the child is 8-9 years of age.

Core symptoms must impair function in

academic, social, or occupational activities for a child to be diagnosed

with ADHD. Early diagnosis is essential to avoid further compromise of

functional achievement [5].

ADHD and Life-stage

Pre-school children: High activity level, poor

inhibitory control and short attention span are common even in typically

developing pre-school children. ADHD should be suspected in case of

increased precarious behaviors and physical injuries or unmanageable

behaviors across different settings. Combined type of ADHD is most

common in this group and persists in 60-80% of children in school-age.

Schoolchildren: School children have relatively

stable attention levels and experience decrease in hyperactivity.

However, 70% of these children have co- morbidities such as Oppositional

defiant disorder and Specific learning disorder. ADHD has a major impact

on peer and family interactions and academics, thereby influencing

parent’s reporting of presenting concerns.

Adults: At age 25 years; 15% individuals meet the

full criteria for ADHD and ~65% are in partial remission. Symptoms of

inattention persist more and show slower decline [14].

Co-morbidities: Following

co-morbidities have been identified with ADHD [5]: Oppositional Defiant

Disorder (ODD); Conduct disorders; Learning Disability; Anxiety

disorders; Intermittent explosive disorder; substance abuse disorder;

Antisocial disorder; obsessive compulsive disorder; tic disorder; Autism

spectrum disorder and major depressive disorder.

Diagnosis

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders [5] is used to diagnose ADHD. It is to be

noted that diagnostic criteria (without subtyping) can be applied to

children as young as 4 years of age [11]. On the other hand, adolescents

may under-report core symptoms or functional impairment and may spend

too little time at home for parents to be accurate informants. Hence,

the pediatrician must obtain information from at least two

teachers and/or other adults with whom the adolescent interacts (e.g.,

counselor, coaches, etc) [11]. The diagnostic tools mentioned (i.e.

Child Behavior Check-List, Connors abbreviated rating scale and

Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale) have not been validated

in the Indian population. The only freely available tool (based on

fourth edition of DSM) that can be used for diagnosis of ADHD in the

Indian context is the INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for ADHD (INDT-ADHD) [12].

The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values

for the same are 87.7%, 97.2%, 98% and 83.3%, respectively. INDT-ADHD

has an internal consistency of 0.91 and a moderate convergent validity

with Conner’s Parents Rating Scale (r =0.73) [12]. The INCLEN tool is

available in English, Hindi, Odia, Konkani, Urdu, Khasi, Gujrati, Telgu

and Malayalam [12]. The time taken for its administration (excluding

scoring time), as observed in clinic-settings, is 15-30 minutes

(approx.).

Differential diagnosis: The symptoms of ADHD

overlap with a number of other conditions, including developmental

variations; neurologic or developmental conditions; emotional and

behavioral disorders; psychosocial or environmental factors, and medical

conditions [11,13-14]. Detailed history of the child and family,

examination, psychometric testing, laboratory investigations, and

genetic testing would help to establish the diagnosis. Few salient

conditions to be differentiated include hyperactive/inattentive

behaviors but within normal range for the child’s developmental level

and not impairing function, intellectual disability, learning

disability, autism, language or communication disorder, anxiety disorder

and motor incoordination disorder. Children with ADHD and with clinical

features of autism should also receive genetic testing to rule out

Fragile X syndrome. In areas that are known to be endemic for lead

toxicity, a blood lead examination is indicated. Children in cities are

at higher risk of lead toxicity due to vehicular traffic pollution and

in case of use of leaded petrol. An audiological examination should also

be conducted to rule out a hearing impairment.

Evaluation and Assessments

Any child 4 through 18 years of age, who presents

with academic or behavioral problems and symptoms of inattention,

hyperactivity, or impulsivity, should be evaluated [11]. Information

should be obtained from parents or guardians, teachers, and other school

and mental health clinicians involved in the child’s care. Comprehensive

evaluation for ADHD includes: a) Confirmation of core symptoms

for presence, persistence, pervasiveness and functional complications;

b) Exclusion of differential diagnoses; and, c) Identification of

co-existing emotional, behavioral and/ or medical disorders. Such a

comprehensive evaluation requires review of medical, social, and family

histories, clinical interviews with the parent and patient, and

information on functioning in school or day-care [11,15,16].

Medical evaluation: Important aspects of medical

history include prenatal exposures (tobacco, drugs, alcohol), perinatal

complications or infections, head trauma, central nervous system

infection, recurrent otitis media, history of sleep disturbances,

medications, family history of similar behaviors, and detailed child and

family cardiac history before initiating medications [11,16,17].

Physical examination: Physical examination is

normal in most children with ADHD. Vision and hearing assessments are

mandatory. It is essential to rule out differential diagnoses. Equally

important is to document the following at each visit: height, weight,

head circumference, and vital signs, assessment of dysmorphic features

and neuro-cutaneous abnormalities, a complete neurologic examination,

and observation of the child’s behavior in the clinic [18].

Developmental and behavioral evaluation: This

includes age of onset of core symptoms, their duration, settings in

which the symptoms occur, and degree of functional impairment or

functional impact of ADHD symptoms. Further information needed is

developmental milestones, especially language milestones, school

absences, psychosocial stressors, emotional, medical, and developmental

events that may provide an alternative explanation for the symptoms (i.e.,

different diagnostic conditions). Observation of parent-child

interactions in the office is an important component of assessment.

Information about core symptoms can be obtained

through open-ended questions or from ADHD-specific rating scales. The

pediatrician must document the presence of relevant behaviors from DSM-5

[16].

Educational evaluation: This includes completion

of an ADHD-specific rating scale; a detailed summary of classroom

behavior and interventions, learning patterns, and functional impairment

at school; evaluation of copies of report cards and samples of

schoolwork; and a review of school-based multidisciplinary evaluations

(if performed).

The teachers who provide the information should have

regular contact with the child for a minimum of four to six months, if

they are to comment reliably on the persistence of symptoms. If there

are discrepancies between parent and teacher reports, then information

should be obtained from professionals working in after-school programs

or other structured settings. Environmental factors (e.g., different

expectations, levels of structure, or behavior management strategies)

may be contributing to these symptoms [11].

Management

Children with ADHD, 4 to 18 years of age, without

co-morbid conditions can usually be managed by the primary pediatrician.

Completion of ADHD rating scales by parents and teachers during the

diagnostic evaluation helps to establish the presence of core symptoms

in multiple settings [19]. Modalities of management of ADHD include

behavioral interventions, medication and educational interventions

(alone or in combination). Since children with ADHD or its symptoms are

at an increased risk of intentional and unintentional injury, safety and

injury prevention should be discussed during each visit [5,11].

Table I summarizes behavioral and educational interventions.

TABLE I Behavioral and Educational Interventions

|

Type of intervention |

Components |

Age group |

|

Behavioral intervention |

a)Positive reinforcement; |

For children 4-6 years of age as

|

|

b)Time-out;

|

primary therapy and |

|

c)Response cost (withdrawing rewards/privileges

|

Children >6 years of age and

|

|

when problem behavior occurs) and

|

adolescents, as therapy in addition

|

|

d)Token economy (combination of positive reinforcement

|

to medication

|

|

and response cost) |

|

|

Educational intervention |

The classroom modifications and accommodations include |

Children 5 years and above;

|

|

1. Having assignments written on the board |

depends on the child’s capacity |

|

2. Sitting near the teacher |

|

|

3. Having extended time to complete tasks |

|

|

4. Being allowed to take tests in a less distracting environment |

|

|

5. Receiving a private signal from the teacher when the child

|

|

|

is ‘off-task’ |

|

|

6.Being assigned a ‘Study Buddy’ |

|

|

7.Being assigned a ‘Shadow Teacher’ |

|

The teacher may submit a report card at regular

intervals, which helps to monitor symptoms and the need for changes in

the treatment plan [24].

Age and choice of intervention

For children 4-6 years of age:

• Behavioral Intervention (BI), rather than

medication, is the initial therapy.

• Addition of medication is indicated if target

behaviors do not improve with BI and the child’s functioning

continues to be impaired.

• Methylphenidate is preferred rather than

amphetamines or Atomoxetine.

For children >6 years of age and adolescents [11,25]:

• Treatment with medication rather than BI alone

or no intervention.

• Stimulant drugs are the first line agents.

Non-stimulants are second line agents.

• BI should be added to medication therapy.

Adding behavioral/ psychological therapy to stimulant

therapy in school-aged children and adolescents does not provide

additional benefit for core symptoms of ADHD, but has an impact on:

• Symptoms of coexisting conditions (e.g.,

oppositional/ aggressive behavior)

• Educational performance

• Dose of stimulant therapy necessary to achieve

the desired effects.

Behavioral Interventions

Parent-child behavioral therapy is aimed at improving

parent-child relationships through enhanced parenting techniques.

Behavioral interventions are most effective if parents understand the

principles of behavior therapy (i.e., identification of

antecedents and altering the consequences of behavior) and the

techniques are consistently implemented [11,20-22]. Indications of

behavioral intervention include: (a) Initial intervention for

preschool children with ADHD (preferred to medication); (b)

Adjunct to medication for school-aged children and adolescents with

ADHD; (c) For children who have problems with inattention,

hyperactivity, or impulsivity but do not meet criteria for ADHD (sub-syndromic).

Specific interventions include: (a) Positive reinforcement; (b)

Time-out; (c) Response cost (withdrawing rewards/ privileges when

problem behavior occurs) and d) Token economy (combination of positive

reinforcement and response cost) [22]. Box 1 provides

useful strategies for parents and teachers to help children with ADHD

regulate their own behavior [11,23].

|

Box 1 Strategies for Parents and Teachers

to Regulate Behaviors in Children with ADHD

1. Maintaining a daily schedule (e.g.,

time table, post- its, reminders)

2. Using charts and checklists to help the

child stay ‘on task’

3. Keeping distractions to a minimum

4. Limiting choices

5. Providing specific and logical places for

the child to keep his school books, toys, and clothes

6. Setting small, reachable goals

7. Rewarding positive behavior (e.g.,

with a ‘token economy’)

8. Identifying unintentional reinforcement of

negative behaviors

9. Finding activities in which the child can

be successful (e.g., hobbies, sports)

10. Using calm discipline (e.g., time

out, distraction, removing the child from the situation)

|

Educational interventions

Children with ADHD may require changes in their

educational program, including (a) Provision of tutoring or

resource room support (either in a one-on-one setting or within the

classroom), (b) Classroom modifications, (c)

Accommodations, and (d) Behavioral interventions [11,23].

Pharmacologic Intervention

The drugs used for management of ADHD and their

side-effects are detailed in Tables II, III and IV.

The choice of medication depends on whether the child is in preschool in

which case a stimulant (Methylphenidate) may be given, if indicated. For

a school-aged child or adolescent, a stimulant is the first-line

agent, followed by amphetamines or a monoamine reuptake inhibitor i.e.,

Atomoxetine. Other medications (e.g., Alpha-2-adrenergic

agonists) usually are used when children respond poorly to a trial of

stimulants or Atomoxetine, or when children have unacceptable side

effects or significant coexisting conditions. The duration of action of

the recommended drug and the child’s ability to swallow pills also

influence the choice of medication.

TABLE II Medications for ADHD

|

Type of drug |

Name of the drug |

Dosage forms |

Duration of action |

Dosage |

Maximum dose |

|

Stimulant |

Methylphenidate |

5 mg, 10 mg and

|

3-5 hours |

Start with 5 mg/day for 1st day;

|

£25 kg: 35 mg;

|

|

|

20 mg tablets |

|

then 5 mg twice a day |

>25 kg:60 mg.

|

|

Stimulant |

Delayed onset

|

5 mg, 10 mg and |

3-8 hours

|

5 mg/day twice daily dosing;

|

£50 kg: 60 mg |

|

methylphenidate |

20 mg tablets |

|

increments of 20 mg per day,

|

>50 kg: 100 mg.

|

|

|

|

|

every 3-7 days |

|

|

Non-stimulant |

Atomoxetine |

10, 18 and 25 mg |

10-12 hours |

Start with 0.5 mg/kg per day |

100 mg per day or

|

|

|

|

|

for minimum 3 days and

|

1.4 mg/kg, |

|

|

|

|

increase to 1.2 mg/kg per day |

whichever is lesser

|

|

|

|

|

after at least 3 days |

|

TABLE III Side-effects of Stimulant Medications and Management

|

Side-effects |

Management |

|

Decreased appetite |

Counsel on high-protein, high-calorie diet and frequent snacks;

advise on medication after meals |

Tics

|

If distressing, taper or discontinue stimulant medication and

consider guanfacine ER or clonidine ER monotherapy or

augmentation |

|

Poor growth |

No action as ultimate adult height is not compromised |

|

Dizziness |

Self-resolving; symptomatic treatment |

|

Insomnia/nightmares |

Sleep hygiene; encourage natural sleep; melatonin as needed |

Mood lability

|

Look for direct effect of medication (emotional symptoms

correlate with expected time of medication effect) – if present,

discontinue medication; if rebound effect (emotional symptoms

occur later in day as medication expected to wearing off), then

add short-acting stimulant in afternoon |

|

Rebound symptoms

|

Add short-acting stimulant in afternoon; add slow-release

tablets

|

TABLE IV Side-effects of Non-stimulant Medications and Management

|

Side-effects |

Management |

|

Gastrointestinal distress |

Typically self-resolves; symptomatic care |

|

Headache |

Typically self-resolves; symptomatic care |

|

Sedation (drowsiness) |

Administer medication at bed-time |

|

Transient growth effects |

No action; adult height not affected |

|

Elevated blood pressure or heart rate |

No action if within age appropriate norms and asymptomatic |

|

Suicidal ideation, hepatotoxicity, priapism (rare) |

Counsel families on warning signs and symptoms of hepatotoxicity;

discontinue medication; re-evaluation of the child |

Stimulants are preferred to other medications because

stimulants have rapid onset of action, and a long record of safety and

efficacy. Individual differences in metabolism are more significant than

weight-based dosing of stimulant medications. The optimal regimen is

determined by changes in core symptoms and occurrence of side effects

[18,26].

Stimulant medications usually are started at the

lowest dose that produces an effect and increased gradually (e.g., every

3-7 days) until core symptoms improve by 40% - 50% compared with

baseline, or adverse effects become unacceptable. The frequency of

stimulant medication (i.e., both, times per day and days per week) is

based upon the type of ADHD and the functional domains in which

improvement is desired. Onset of action is very important in a

school-going child. At a therapeutic dose, the effects of stimulant

medications on core symptoms usually are apparent in 30-40 minutes after

administration and continue for the expected duration of action.

Appetite suppression may indicate treatment response. Inadequate dose

may be indicated by shorter than expected duration of action [18].

A child with the predominantly inattentive type of

ADHD may need medication only on school days. A child who has difficulty

with peer relationships may need medication every day. A child who

participates in after-school sports or activities on certain days of the

week may require longer-acting preparations or more frequent dosing on

those days. Optimal dose is the dose at which target outcomes are

achieved with minimal side effects.

Parents should be advised that 2-6 weeks of

medication maybe needed for any therapeutic effect to show and before

dose-reduction is considered. If side-effects are severe, the clinician

may decrease the dose of medication or change to another ADHD medication

(stimulant or non-stimulant) [27].

After several years of medication, children and

adolescents who have had stable improvement in ADHD symptoms and target

behaviors are offered a trial off, of medication to determine whether

medication is still necessary. If symptoms re-appear, after a period of

remission, consider the risk factors/stressors that have led to the same

and counsel parents on mitigating those; and resume medication. Children

with ADHD may require changes in their educational programming.

Combination therapy with medications and behavior/ psychological therapy

is superior to behavior/ psychological therapy alone and necessary for

restoration of function and inclusion.

Combination Therapy

Combination therapy uses both behavioral

interventions and medications. Combination therapy may be warranted in

preschool children who do not respond to behavioral interventions.

In a systematic review and a meta-analysis,

combination therapy with medications and behavior/psychological therapy,

was superior to behavior/ psychological therapy alone. Children

receiving combination therapy may require lower doses of medication and

achieve greater improvement in non-ADHD symptoms (e.g.,

oppositional/aggressive, internalizing, teacher-rated social skills,

parent-child relations and reading achievement) than children receiving

medication alone. Cognitive behavioral therapy may be a helpful adjunct

to medications for adolescents with ADHD. Dietary interventions are not

recommended.

Referral to a developmental pediatrician, child

neurologist or child psychiatrist is needed in case of Co-morbid

conditions (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder,

substance abuse, emotional problems); b) Coexisting neurologic or

medical conditions (e.g., seizures, tics, autism spectrum disorder,

sleep disorder); c) La) Lack of response to a controlled trial of

stimulant or Atomoxetine therapy [25, 28-30].

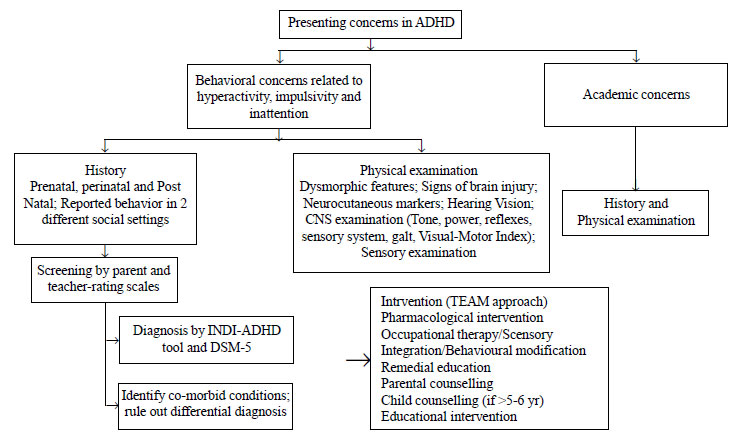

Fig.1 provides a flowchart for the management

of ADHD.

|

|

Fig. 1 Flowchart for management of

ADHD.

|

Disability Certification

Government organizations, the Persons with Disability

Act (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full

Participation),1995, and the National Trust for the Welfare of Persons

with Autism, Cerebral Palsy, Mental Retardation and Multiple

Disabilities act, 1999, do not recognize ADHD as a neurodevelopmental

disorder. Currently, there are no provisions for certifying children

with ADHD. However, the Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) focuses

on early detection and intervention of disease, disabilities,

deficiencies and developmental problems including ADHD. Owing to the

fact that it is the most common childhood neuro-behavioural disorder;

high prevalence rates in India, and the dire need for affected children

to receive sustained multidisciplinary interventions over a long period,

the expert group strongly recommends disability certification for ADHD.

Conclusion

ADHD is characterized by behavioral, emotional and

academic concerns, and requires a range of interventions such as

medications, behavioural intervention, occupational therapy/sensory

integration, remedial education, parent and child counselling and

classroom modifications. A comprehensive inter-disciplinary approach

leads to sustained alleviation of symptoms and greater capacity-building

of caregivers and children to adjust with the disease over the long

term.

1. Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, Biederman J.

The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: is it an American condition? World

Psychiatry. 2003;2:104-13.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American

Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Venkata JA, Panicker AS. Prevalence of attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary school children. Indian J

Psychiatry. 2013;55:338-42.

4. Duggal C, Dalwai S, Bopanna K, Datta V, Chatterjee

S, Mehta N. Childhood Developmental and Psychological Disorders: Trends

in Presentation and Interventions in a Multidisciplinary Child

Development Centre. Indian J Soc Work. 2014;75:495-522

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition. Arlington, VA:

American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Naik A, Patel S, Biswas DA. Prevalence of ADHD in

a rural Indian population. Innovative J Med and Health Science.

2016;6:45-6.

7. Suvarna BS, Kamath A. Prevalence of attention

deficit disorder among preschool age children. Nepal Med Coll J.

2009;11:1-4.

8. Levin FR, Kleber HD. Attention-deficit

hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse: relationships and

implications for treatment. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1995;2: 246-58.

9. Weiler MD, Bernstein JH, Bellinger DC, Waber DP.

Processing speed in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity

disorder, inattentive type. Child Neuropsychol. 2000;6:218-34.

10. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The

age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a

meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med. 2006; 36:159-65.

11. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity

Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management.

ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and

treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and

adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011.

12. Mukherjee S, Aneja S, Russell PS, Gulati S,

Deshmukh V, Sagar R, et al. INCLEN diagnostic tool for attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder (INDT-ADHD): Development and validation.

Indian Paediatr. 2014;51:457-62.

13. Krull KR, Augustyn M, Torchia M. Attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Clinical

features and evaluation. [cited 2012]. Available from:

http://www.uptodate.com/contents/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-in-children-and-adolescents-clinical-features-and-evaluation?source=search_

result&search=attention+deficit+hyperactivity+

disorder+children&selected Title=2~150. Accessed January 23, 2016.

14. Gilger JW, Pennington BF, DeFries JC. A twin

study of the etiology of comorbidity: attention-deficit hyperactivity

disorder and dyslexia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

1992;31:343-8.

15. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health,

UK. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management

of ADHD in children, young people and adults. [cited 2009]. Available

from:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0034228/toc/?report=reader.

Accessed January 23, 2016.

16. Taylor E, Döpfner M, Sergeant J, Asherson P,

Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, et al. European Clinical Guidelines

for Hyperkinetic Disorder–First Upgrade. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2004;13:i7-i30.

17. Sedky K, Bennett DS, Carvalho KS. Attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder and sleep disordered breathing in

pediatric populations: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:349-56.

18. Wender EH. Managing stimulant medication for

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Rev. 2001;23:234-6.

19. Collett BR, Ohan JL, Myers KM. Ten-year review of

rating scales. V: scales assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1015-37.

20. Charach A, Carson P, Fox S, Ali MU, Beckett J,

Lim CG. Interventions for preschool children at high risk for ADHD: a

comparative effectiveness review. Pediatrics. 2013;131:1-21.

21. Kaplan A, Adesman A. Clinical diagnosis and

management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in preschool

children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:684-92.

22. Floet AL, Scheiner C, Grossman L.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Paediatr Rev. 2010;31:56-69.

23. American Academy of Pediatrics. Understanding

ADHD. Information for parents about attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder. [cited 2001]. Available from:

http://www.pediatricenter.org/docs/ADHD%20AAP%20hand out_HE0169.pdf.

Accessed January 23, 2016.

24. Manansala MA, Dizon EI. Shadow teaching scheme

for children with autism and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder in

regular schools. Educ Q. 2010;66:34-49.

25. Pliszka S. AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues.

Practice parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and

Adolescents with Attention-deficit/hyperactivity Disorder. J Am Acad

Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:894-921.

26. Kaplan G, Newcorn JH. Pharmacotherapy for child

and adolescent attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Paediatr Clin N

Am. 2011;58:99-120.

27. Southammakosane C, Schmitz K. Pediatric

psychopharma-cology for treatment of ADHD, depression, and anxiety.

Pediatrics. 2015;136:351-9.

28. The MTA Cooperative Group. Multimodal Treatment

Study of Children with ADHD. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of

treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch

Gen Psychiatry. 1999; 56:1073-86.

29. Brown RT, Amler RW, Freeman WS, Perrin JM, Stein

MT, Feldman HM, et al. American Academy of Paediatrics Committee

on Quality Improvement; American Academy of Paediatrics Subcommittee on

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Paediatrics.

2005;115:e749-e57.

30. Van der Oord S, Prins PJ, Oosterlaan J, Emmelkamp

PM. Efficacy of methylphenidate, psychosocial treatments and their

combination in school-aged children with ADHD: a meta-analysis. Clin

Psychol Rev. 2008;28:783-800.