|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: 485-495 |

|

Cognitive

Functions and Psychological Problems in Children with Sickle

Cell Anemia

|

|

Gauthamen Rajendran, Padinharath Krishnakumar,

*Moosa Feroze and Veluthedath

Kuzhiyil Gireeshan

From Institute of Maternal and Child Health, and

*Department of Psychology; Government Medical College, Kozhikode, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Gauthamen Rajendran,

Clinical Fellow, Department of Neonatal Medicine, Women’s Center, John

Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom, OX39DU.

Email: [email protected]

Received: September 02, 2015;

Initial review: October 23, 2015;

Accepted: March 08, 2016

|

Objective: To study the cognitive functions and psychological

problems in children with Sickle cell anemia (SCA).

Methods: Children with SCA were compared with an

age-, sex- and community- matched control group of children with no SCA.

Malin’s Intelligence Scale for Indian children, modified PGI memory

scale, and Childhood Psychopathology Measurement Schedule were used to

assess cognitive functions and psychological problems.

Results: Verbal quotient, performance quotient

and intelligence quotient in SCA group were 77, 81, 78, respectively

versus 92, 95, 93, respectively in non-SCA group (P <0.001).

Borderline intellectual functioning and mild mental retardation were

more common in SCA (70% and 16%, respectively). Children with SCA had

impaired attention, concentration and working memory and more behavior

problems compared to children without SCA.

Conclusions: Cognitive functions are impaired in

children with SCA and they have more psychological problems. Facilities

for early identification and remediation of psychological and

intellectual problems should be incorporated with health care services

for children with sickle cell anemia.

Keywords: Behavioral problems, Intellectual disability,

Memory, Psychopathology.

|

|

S

ickle cell anaemia (SCA) is the most common

inherited hematological disorder world-wide. It is estimated that about

18 to 34 % of the tribal population in the Wayanad district of Kerala,

India suffer from SCA [1,2].

Studies from abroad have reported neurocognitive and

developmental problems associated with SCA [3,4]. Very few authors have

studied the cognitive functions and psychological problems in children

with SCA in India [5].

The Government of Kerala provides comprehensive care

to children with SCA through monthly sickle cell anemia clinics

conducted in primary health centers in the district. The present study

aimed to assess the cognitive functions and psychological problems of

children with SCA attending the monthly clinics.

Methods

The study period was from February 2011 to July 2012

and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional ethics

committee of Government. Medical College, Kozhikode. Fifteen monthly SCA

clinics conducted in Wayanad, provide comprehensive healthcare to 276

children with SCA in the age group of 0-15 years. The study was

conducted in 8 of these SCA clinics. A total of 18 visits were required.

Children in the 6-15 year age group attending the SCA clinics, who were

already diagnosed to have SCA by hemoglobin electrophoresis or high

performance liquid chromatography were included in the study after

obtaining informed consent from their parents. Children with sickle cell

crisis, history of stroke, other chronic illnesses, and neurological

disorders were excluded.

Children with no SCA who were attending the same

primary health center for minor illnesses were included in the control

group. The children in the control group were screened negative for SCA

by clinical examination and solubility test. Children in the study group

and control group were matched for age, sex and community.

All children were evaluated using Malin’s

Intelligence Scale for Indian Children (MISIC), Childhood

Psychopathology Measurement Schedule (CPMS), and modified PGI Memory

Scale. The evaluation was done by a pediatric resident trained in the

use of the scales. Every child was allotted one hour, 25 minutes and 15

minutes for MISIC, PGI memory scale and CPMS tests, respectively and all

tests were done in a single sitting.

MISIC is the Indian adaptation of Wechsler’s

intelligence scale for children. It gives a verbal quotient (VQ),

performance quotient (PQ) and total quotient (IQ) [6]. CPMS is a

parent-reported rating scale for children of age 4 to 14 years [7]. CPMS

scale translated to the local language for the purpose of the study by

the investigators was given to the parent and each item in the scale was

explained to them to get the response.

The PGI memory scale contains 10 subtests and is

standardised for adults [8]. A modified version of PGI memory scale was

found to be applicable in Indian children [9]. In the present study,

three questions in remote memory subtest were modified to be applicable

to children and the modified questionnaire was tested in ten normal

children to check for their ability to answer the questions.

The data was entered in excel data sheet and analyzed

using the SPSS 10.0 software. Two-tailed paired t test was used to

assess the statistical significance and a P value of less than

0.05 was taken as statistically significant. Correlation of age with the

deterioration of cognitive functions of both cases and controls were

done using scatter plots of IQ.

Results

Fifty eight children with SCA in the age group of 6

-15 years attended the SCA clinics during the visits. Out of them, three

had seizure disorder, two had bronchial asthma, five refused to

participate in the study, and four opted out of the study because of the

time consuming intelligence tests. Thus, study and the control group

finally consisted of 44 children (25 boys and 19 girls) in the 6-15 year

age group. The mean age was 9.9 (2.67) years. All of them were receiving

comprehensive care for the last four years. Thirty two children (72.7%)

in each group belonged to Paniya community while 10 children (22.7%)

were from Kuruma community.

TABLE I MISIC Scores in Children With and Without Sickle Cell Anemia

|

Quotient |

Score (SD) |

Difference (SD) |

|

SCA |

Control |

|

|

Group |

Group |

|

|

Verbal Quotient |

77(6.7) |

92 (7.2) |

15 (6.7) |

|

Performance Quotient |

81 (7.5) |

95 (7.2) |

14 (7) |

|

Intelligence Quotient |

78 (7.5) |

93 (7.1) |

15 (6.4) |

|

P<0.001 for all comparisons; SCA: Sickle cell anemia. |

Children with SCA had lower IQ scores across all

subgroups in both verbal and performance domains (Table I)

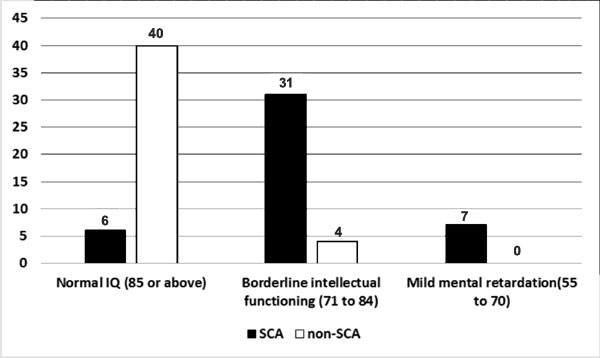

Children with both mild mental retardation and border intellectual

function were higher in the SCA group than non-SCA group (P<0.001) (Fig.

1). None of the children had moderate or severe mental retardation.

There was no statistical evidence to suggest deterioration of IQ with

advancing age in children with SCA.

|

|

Fig. 1 Prevalence of

intellectual disability in children with and without Sickle-cell

anemia.

|

Mean raw scores of all the eight subtests in the PGI

memory scale, showed statistically significant difference (P

<0.05) between children with SCA and children in the control group (Table

II). The children in the study groups could not perform the delayed

recall and retention of dissimilar pair subtests of the PGI memory scale

and hence not included in the study.

TABLE II PGI Memory Scale Scores in Children With and Without Sickle Cell Anemia

|

Parameter |

Score (SD)

|

|

SCA Group |

Control Group |

|

Remote memory |

3 (1.3) |

4 (1.4) |

|

Recent memory |

1 (0.6) |

2 (1) |

|

Mental balance |

1 (0.4) |

2 (0.5) |

|

Attention and concentration |

6 (2.1) |

8 (1.6) |

|

Immediate recall |

1 (0.2) |

2 (0.5) |

|

retention of similar pairs |

2 (0.9) |

3 (0.8) |

|

Visual retention |

2 (0.8) |

3 (0.9) |

|

Recognition |

2 (0.9) |

3 (0.9) |

|

P<0.001 for all comparisons; SCA: Sickle cell anemia. |

Children in the study group and control group had

scores below the cut-off value of 10 on the CPMS scale, but there was

statistically significant difference between the mean score 4.09 (2.23)

vs. 2.43 (1.58), respectively. On analysis of the subscales of

CPMS, children in the SCA group scored significantly more on the

behavior problem subscale (P=0.002) and the difference was not

statistically significant on other items.

Even after applying ANCOVA (Analysis of co-variance)

there was statistically significant difference in the cognitive

functions (VQ, PQ and IQ) and CPMS score (P<0.05).

Discussion

The present study compared cognitive functions and

psychological problems in children with SCA with an age-, sex- and

community-matched control group of children with no SCA. It was found

that children with SCA had impaired cognitive functions and more

psychological problems compared to children in the control group.

Borderline intellectual functioning and mild mental retardation were

more commonly seen in children with SCA.

Our findings on cognitive functions in children with

SCA are comparable to the results of previous studies which have

reported lower IQ scores in children with SCA [10-12]. The causes of

cognitive impairment in SCA include brain infarction and chronic brain

hypoxia due to low hematocrit and thrombocytosis [11,12]. Since children

with history of stroke were excluded, silent infarcts and chronic brain

hypoxia may be the causes for cognitive impairment in the children in

the present sample.

Age related decline in cognitive functions has been

reported by several studies in the past [10]. In the present study no

correlation was observed between advancing age and cognitive decline.

This may be due to the fact that majority of children in our sample were

below 12 years, and also due to the small sample size.

A previous study from India found that children with

SCA have poor quality of life and all domains viz. physical,

psychological and cognitive domains are affected [5]. In the present

sample even though all children had scores below the cut-off value on

the CPMS, the scores were significantly higher compared to those of the

children in the control group indicating that children with SCA have

more psychological problems. Other studies have reported that

psychological disorders like anxiety and depression are more frequent in

children with SCA [13,14]. Gold, et al. [15] have reported that

even though children with SCA have no more behavior problems compared to

their siblings, they have more behavior problems compared to the general

population. In the present sample children with SCA differed

significantly on the behavior problem subscale of the CPMS. The reason

for this may be that psychological disorders commonly occur when the

children reach adolescence, and psychological distress in young children

most often present with externalizing behaviors.

The strengths of the present study include the fact

that study was conducted in a community-setting, the control group was

recruited from the same tribal community, and one-to-one matching was

done. Since the sample of children with SCA belonged to a tribal

population with unique social and cultural characteristics,

generalization of the result should be with caution. Small sample size

and lack of blinding while doing the tests are also limitations of the

study.

The present study emphasizes the importance of

assessment of cognitive functions and psychological well-being in

children with sickle cell anemia. Facility for early identification and

remediation of cognitive impairments and psychological problems should

be considered while planning health care services for children with

sickle cell anemia.

Acknowledgement: Professor Dr A Riyaz, Department

of Pediatrics, for his constant guidance and encouragement for the

completion of the study. Dr. Biju, Assistant Professor, Department of

Social and Preventive Medicine, for his supervision and guidance in the

analysis of the data.

Contributors: GR: conceptualized and designed the

study, designed data collection instruments, collected data, carried out

initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final

manuscript as submitted; PK, MF, and VKG: carried out the further

analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final

manuscript as submitted.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Children with sickle cell anemia have impaired cognitive

functions and more psychological problems compared to children

without sickle cell anemia.

|

References

1. Feroze M, Aravindan KP. Sickle cell disease in

Wayanad, Kerala: Gene frequencies and disease characteristics. Nat Med J

India. 2001;14:267.

2. Colah RB, Mukherjee MB, Martin S, Ghosh K. Sickle

cell disease in tribal populations in India. Indian J Med Res.

2015;141:509-15.

3. Armstrong FD, Elkin TD, Brown RC, Glass P, Rana

S, Casella JF, et al. Developmental function in toddlers with

sickle cell anemia. Pediatrics. 2013;131:406-14.

4. Glass P, Brennan T, Wang J, Luchtman-Jones L, Hsu

L, Bass CM, et al. Neurodevelopmental deficits among infants and

toddlers with sickle cell disease. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34:399-405.

5. Patel AB, Pathan HG. Quality of life in children

with sickle cell hemoglobinopathy. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:567-71.

6. Malin AJ. Manual for Malin’s Intelligence Scale

for Indian Children (MISIC). Lucknow: Indian Psychological Corporation,

1969.

7. Malhotra S, Varma VK, Verma SK, Malhotra A. A

childhood psychopathology measurement schedule: Development and

standardization. Indian J Psychiatr. 1988;30:325-32.

8. Prashad D, Wig NN. PGI memory scale (revised

manual) PGIMER, Chandigarh, National Psychological Corporation, 1988.

9. NS Gajre, Fernandez S, Balakrishna N, Vazir

S. Breakfast eating habit and its influence on attention-concentration,

immediate memory and school achievements. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:824-8.

10. Steen RG, Fineberg-Buchner C, Hankins G, Weiss

L, Prifitera A, Mulhern RK. Cognitive deficits in children with sickle

cell disease. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:102-7.

11. Steen RG, Miles MA, Helton KJ, Strawn S, Wang W, Xiong

X, et al. Cognitive impairment in children with hemoglobin SS

sickle cell disease: relationship to MR imaging findings and hematocrit.

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:382-9.

12. Hogan AM, Pit-ten Cate IM, Vargha-Khadem F, Prengler

M, Kirkham FJ. Physiological correlates of intellectual function in

children with sickle cell disease: hypoxaemia, hyperaemia and brain

infarction. Dev Sci. 2006;9:379-87.

13. Schatz J, Roberts CW. Neurobehavioral impact

of sickle cell disease in early childhood. J Int Neuropsychol

Soc. 2007;13:933-43.

14. Unal S, Toros F, Kütük MÖ, Uyanýker MG.

Evaluation of the psychological problems in children with sickle cell

anemia and their families. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;28:321-8.

15. Gold JI, Mahrer NE, Treadwell M, Weissman L,

Vichinsky E. Psychosocial and behavioral outcomes in children with

sickle cell disease and their healthy siblings. J Behav Med. 2008;

31:506-16.

|

|

|

|

|