|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51:

457-462 |

|

INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder (INDT-ADHD):

Development and Validation

|

|

Sharmila Mukherjee, Satinder Aneja, Paul SS Russell, Sheffali Gulati,

Vaishali Deshmukh, Rajesh Sagar, Donald Silberberg, Vinod K Bhutani,

Jennifer M Pinto, Maureen Durkin, Ravindra M Pandey, MKC Nair, Narendra

K Arora and *INCLEN Study

Group

From The INCLEN Trust International, New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Narendra K Arora, Executive Director, The

INCLEN Trust International, F1/5, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-1, New

Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: April 03, 2013;

Initial review: May 08, 2013;

Accepted:

February 15, 2014.

*INCLEN Study Group: Core Group: Alok Thakkar, Arun

Singh, Devendra Mishra, Gautam Bir Singh, Manju Mehta, Manoja K Das,

Monica Juneja, Nandita Babu, Poma Tudu, Praveen Suman, Ramesh Konanki,

Rohit Saxena, Savita Sapra, Sunanda K Reddy, Tanuj Dada. Extended

Group: AK Niswade, Archisman Mohapatra, Arti Maria, Atul Prasad,

BC Das, Bhadresh Vyas, GVS Murthy, Gourie M Devi, Harikumaran Nair, JC

Gupta, KK Handa, Leena Sumaraj, Madhuri Kulkarni, Muneer Masoodi, Poonam

Natrajan, Rashmi Kumar, Rashna Dass, Rema Devi, Sandeep Bavdekar,

Santosh Mohanty, Saradha Suresh, Shobha Sharma, Sujatha S Thyagu, Sunil

Karande, TD Sharma, Vinod Aggarwal, Zia Chaudhuri.

|

Objective: To develop and validate INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (INDT-ADHD).

Design: Diagnostic test evaluation by cross

sectional design.

Setting: Tertiary care pediatric centers.

Participants: 156 children aged 65-117 months.

Methods: After randomization, INDT-ADHD and

Connor’s 3 Parent Rating Scale (C3PS) were administered, followed by an

expert evaluation by DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria.

Main outcome measures: Psychometric evaluation of

diagnostic accuracy, validity (construct, criterion and convergent) and

internal consistency.

Results: INDT-ADHD had 18 items that quantified

symptoms and impairment. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder was

identified in 57, 87 and 116 children by expert evaluation, INDT-ADHD

and C3PS, respectively. Psychometric parameters of INDT-ADHD for

differentiating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and normal

children were: sensitivity 87.7%, specificity 97.2%, positive predictive

value 98.0% and negative predictive value 83.3%, whereas for

differentiating from other neuro-developmental disorders were 87.7%,

42.9%, 58.1% and 79.4%, respectively. Internal consistency was 0.91.

INDT-ADHD has a 4-factor structure explaining 60.4% of the variance.

Convergent validity with Conner’s Parents Rating Scale was moderate (r

=0.73, P= 0.001).

Conclusions: INDT-ADHD is suitable for diagnosing

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Indian children between the

ages of 6 to 9 years.

Keywords: Childhood neuro-developmental disorders, Resource

limited settings, Psychometric evaluation.

|

|

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) has 3-5% prevalence in

school- aged children worldwide [1,2]. The diagnosis of ADHD is purely

clinical and challenging as the developmental level and co-morbid

disorders affect manifestations. Subjectivity arises in recognition of

symptoms and degree of functional impairment. In the West, studies have

shown that ADHD can be reliably diagnosed across clinicians [3]. This

may not be true in India and other similar settings due to low levels of

awareness and expertise about ADHD in community clinicians. Clinically,

International Classification of Disease-10 (ICD-10) and the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)

criteria are used to diagnose ADHD [4,5]. Both constructs are based on

core symptom clusters of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsiveness.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines for ADHD assessment

advise DSM-IV-TR criteria, evaluating for co-morbid conditions, and a

neurological examination [6].

Appropriateness of construct of the DSM-IV-TR

diagnostic criteria has not been studied in the Indian cultural context.

Moreover, the uses of narrow band rating scales are limited by bias,

cost, extensive training requirement, decreased availability and poor

applicability. Some tools require the teacher’s perspective of the

child’s behavior which may not be as reliable given the high

student-teacher ratios. Appropriateness criteria are evidence-based

guidelines developed to assist physicians and clinical psychologists in

diagnosing conditions with wide variability in clinical decision in such

settings. They are created by blending broad ranges of clinical

experience with evidence-based information. The current study was

planned to develop appropriateness criteria for ADHD in Indian children

(6-9 years of age) and validate a diagnostic tool based on this

criteria.

Methods

Development of Appropriateness Criteria and Instrument

A panel consisting of 49 national experts from

different parts of India and 6 international experts (pediatricians,

child psychiatrists, pediatric neurologists, epidemiologists, pediatric

otorhinolaryngologists, clinical psychologists, special educators,

specialist nurses, speech therapist, occupational therapists and social

scientist) developed the appropriateness criteria and diagnostic tool

over three rounds of two-day workshops conducted during 2006-2008.

Diagnostic modalities of ADHD in children were reviewed, and clinical

expertise regarding personal practice was shared [7]. The former

included ICD-10, DSM-IV-TR, ADHD Comprehensive Teacher Rating Scale-2nd

edition, The Vanderbilt ADHD Teacher Rating Scale, Conner’s Parent and

Teacher Rating Scales-Revised (CPRS-R, CTRS-R), Swanson, Nolan, and

Pelham-IV Questionnaire, and Attention Deficit Disorder Evaluation

Scale-Second Edition [8-13]. A pool of items was selected by the panel

using the modified Delphi technique. Appropriateness criteria comprising

of 18 symptoms, based on parental interview and direct observation, were

finalized based on clarity, importance and frequency of endorsement. The

items were formulated in a construct similar to DSM-IV-TR criterion. The

criteria were converted into symptom clusters for clinicians and

psychologists to rate during diagnostic workup. The tool was named

"INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

INDT–ADHD. The tool was translated forwards and backwards from Hindi

to English and Malayalam by bilingual translators maintaining

conceptual, content, semantic, operational and functional equivalence of

the items, and validated. The tool was similarly prepared in Odia,

Konkani, Urdu, Khasi, Gujarati and Telugu.

Section-A of INDT-ADHD consists of 18 items related

to ‘inattention’ and ‘hyperactivity/impulsiveness’ symptoms (9 items

each) while Section B consists of 8 items pertaining to onset, duration,

functional impairment and a diagnostic algorithm to arrive at the

diagnosis. Scoring is by parental endorsement with ‘1’ for ‘Yes’ and ‘0’

for ‘No’. A score of six or more of the 9 items related to ‘only

inattention’, ‘only ‘hyperactivity/impulsiveness’ and ‘both’ indicate

‘predominantly inattentive’, ‘predominantly hyperactive/impulsive’, and

‘combined subtypes’, respectively. These are considered significant if

the duration of symptom is ≥6

months, onset is before 7 years of age, and manifestation are in at

least two settings. The instrument is given as

Web Appendix I.

Psychometric Evaluation

The evaluation was conducted at four tertiary

pediatric centers [All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS),

Maulana Azad Medical College (MAMC), and Lady Hardinge Medical College

(LHMC) in New Delhi, and Child Development Centre in Thiruvananthapuram]

from June 2008 to April 2010.

Children 6-9 years of age with various

Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs) were recruited from the Child

Development/Neurology outpatient clinics; those with typical development

were recruited from the pediatric outpatient departments. Informed

consent from the accompanying primary caregiver was obtained. The study

was approved by the IndiaCLEN Review Board and individual Institutional

Ethics Committees.

Enrolment and assessment

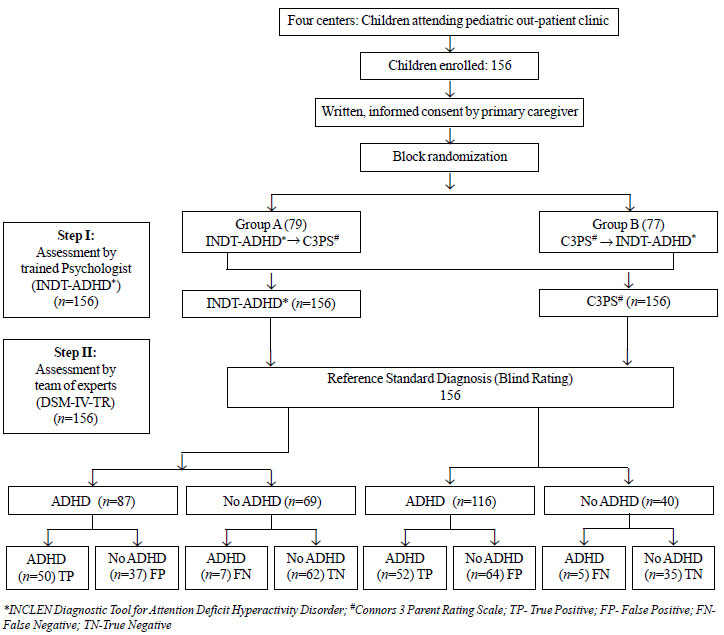

Fig.1 depicts the method for

participant selection, assessment and interview. At every study site,

the study coordinator, who was not part of any assessment, evaluated the

children attending the clinic for eligibility and enrolled them in the

study. The 156 participants were randomly allocated into group A (N=79)

or B (N=77) by block randomization. In group A, INDT-ADHD was

administered followed by Conner’s 3 Parent Rating Scale-Short Form

(C3PS) [14] whereas in group B, the sequence was reversed. This was done

by independent psychologists to minimize rating bias. Thereafter, each

child was assessed by a two member expert team (pediatric neurologist

and child psychiatrist) who based their diagnosis on DSM-IV-TR criteria.

This process took 3.5 hours over two consecutive days for each

participant, comprising of interviews and direct observations. Each

evaluator was blinded to original diagnosis and to the assessment by

each other. After the expert evaluation, parents were counselled

regarding the diagnosis and referrals were facilitated accordingly.

|

|

Fig. 1 The flowchart for

randomization, assessment and interviews.

|

A sample size of 50 was calculated for each of the

three groups (ADHD, children with other NDDs, and with normal

development) assuming 85% sensitivity and specificity of INDT-ADHD to

diagnose ADHD and 90% precision at 95% confidence. It was decided to

enrol 60 children to account for drop-outs. This sample size was

adequate to have an exploratory factor analysis during validation.

Training: The psychologists were trained in

administration of INDT-ADHD and C3PS using a standardized operational

manual in a 3-day structured workshop. Separate groups of psychologists

were formed for INDT-ADHD and C3PS. Two pediatric neurologists and two

child psychiatrists with over 10 years of professional experience were

the trainers. Out of eight trainees, six were Masters in Psychology and

two were Clinical Psychology graduates.

Data management and analysis

Participants’ assessment details were entered in a

pre-designed instrument with unique identification numbers. Blinding was

maintained by separate opaque, sealed envelopes and protected by

reversible anonymity and restricted availability. Statistical analysis

was done using SPSS (version 19) and MedCalc (version 12.2.1.0) after

data was entered into Intelligent Character Recognition sheets (ICR).

These were processed using ABBYY Form Reader 4.0 software. Psychometric

parameters of diagnostic accuracy, construct validity, criterion

validity and internal consistency of INDT-ADHD were estimated. The

performance of INDT-ADHD was compared with C3PS for convergent validity.

Results

Mean (SD) age of enrolled children (N=156; 107

boys) was 89.1 (11.9) months. The diagnoses made by each method is

depicted in Table I. According to expert team (gold

standard), 57 children had ADHD (47 isolated and 10 with other co-morbid

NDD); 26 were predominantly inattentive, 11 predominantly

hyperactive/impulsive and 20 were combined ADHD. INDT-ADHD diagnosed

ADHD in 87 children; 33 predominantly inattentive, 16 predominantly

hyperactive/impulsive and 38 combined. C3PS made a diagnosis of ADHD in

116 cases without any differentiation into sub-types.

TABLE I Final Diagnoses of Study Group According to Experts (N=156)

|

Evaluation by |

Final Diagnosis |

|

ADHD |

Not ADHD |

|

Total |

Isolated ADHD |

With co- morbid NDD |

Total |

NDD/co morbidities |

Normal

|

|

(Break-up)* |

(Break-up)* |

(Break-up)* |

|

other than ADHD |

development |

|

Expert Team$ |

57 |

47 |

10 |

99 |

55# |

44

|

|

(26,11,20) |

(15,14,18) |

(4,3,3) |

|

|

|

|

INDT-ADHD |

87 |

Not done |

Not done

|

69 |

26 |

43

|

|

(33, 16, 38) |

by tool |

by tool |

|

|

|

|

C3PS |

116 (No sub- |

Not done |

Not done |

40 |

12 |

28

|

|

type possible) |

by tool

|

by tool |

|

|

|

|

*Inattention, hyperactivity/impulsiveness, combined.

#ASD-Autism

Spectrum Disorder; ID-Intellectual Disability; SLD-Speech and

Language Disorder; HI-Hearing Impairment; VI-Vision Impairment;

NMI-Neuro-motor Impairment; CP-Cerebral palsy; LD-Specific

Learning Disorders. INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder (INDT- ADHD); Connors Parent Rating Scale

(C3PS) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders- IV-Text Revision (DSM-IV TR). #(ASD

-19, ASD + ID-5, ID-15, SLD- 2, HI-3/ VI-1,

NMI/CP- 3, Epilepsy -2, LD- 5); $Expert team:

diagnosis with DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic criteria of ADHD. |

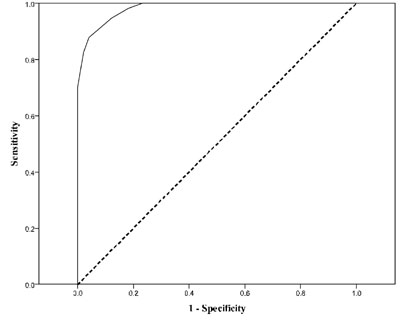

Psychometric parameters of INDT-ADHD are summarized

in Table II. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curve for INDT-ADHD with a cut-off score of ≥8 against expert

diagnosis gave an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.98 [95% CI0.94, 0.99)

[depicted as Fig. 2]. The diagnostic accuracy of

INDT-ADHD against expert diagnosis calculated by AUC according to

age (below and ≥7 years), gender and severity (no ADHD and ADHD)

is presented in Table III. Inter-rater reliability and

test-retest reliability were not assessed. The Cronbach’s

α coefficient

for the whole construct showed high internal consistency (0.91) and good

internal consistency separately for inattention (0.84) and

hyperactivity/impulsiveness (0.87). Construct validity was

demonstrated by exploratory factor analysis (principal component

extraction and varimax rotation). Taking the critical Eigen value as 1,

a 4-factor structure was derived [Web Table I]. Factors 1,

2, 3 and 4 represented inattention, hyperactivity, communication related

restlessness and distractibility, respectively. With loading factor cut

off level of 0.4, 14 items loaded distinctively on to single factors,

eight with inattention, three with hyperactivity, two with communication

related restlessness and one with distractibility, whereas four symptoms

cross-loaded on to more than one factor. This factor analysis explained

60.4% of the variance. When the performance of INDT-ADHD was compared

with that of C3PS it was observed that the convergent validity was

moderate (r = 0.73, P= 0.001).

|

|

Fig. 2 The Receiver Operating Curve

characteristics of INCLEN

Diagnostic Tool for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

(INDT-ADHD) total score against Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders- IV-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)

diagnosis (Expert Diagnosis).

|

TABLE II Diagnostic Accuracy of INDT-ADHD Against the Expert Diagnosis

|

Sensitivity%

(95% CI) |

Specificity%

(95% CI) |

PPV

(95% CI) |

NPV

(95% CI) |

Positive LR

(95% CI) |

Negative LR

(95% CI) |

|

ADHD vs. |

87.7 |

42.9 |

58.1 |

79.4 |

1.5 |

0.28

|

|

other NDD |

(78.6-94.2) |

(34.6-48.7) |

(52.1-62.4) |

(64.1-90.2) |

(1.2-1.8) |

(0.12-0.61) |

|

ADHD vs. |

87.7 |

97.2

|

98.0 |

83.3 |

31.5 |

0.12 |

|

normal |

(81.1-89.4) |

(86.7-99.9) |

(90.6-99.9) |

(74.3-85.6) |

(6.0-610.8) |

(0.10-0.21) |

|

INDT-ADHD |

87.7

|

95.9 |

38.2 |

11.1 |

21.7 |

0.13 |

|

total score ≥8 |

(76.3-94.9) |

(90.0- 98.9) |

(34.9-43.7) |

(0.04 - 0.2) |

(19.5-24.1) |

(0.04-0.4) |

|

INDT- ADHD: INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder; Other NDD: Other Neuro-developmental

disorder; LR: Likelihood ratio; PPV: Postive predictive value;

NPV: Negative predictive value. |

TABLE III Performance of INDT-ADHD Against DSM-IV TR Different Age Groups, Gender and Severity* of ADHD

|

Groups |

AUC (95% CI)

|

|

Age group |

|

|

Children < 7 years |

0.98 (0.96-1) |

|

Children ≥7 years |

0.98 (0.96-1) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Boys |

0.97 (0.95-0.99) |

|

Girls |

0.99 (0.97-0.99) |

|

Severity of ADHD*

|

|

|

No ADHD/Borderline |

0.53 (0.42-64) |

|

Severe |

0.81 (0.69-0.93) |

|

*Severity of ADHD dichotomized into no ADHD/borderline (C3RS

score of 0-56/57-63) and elevated scores (C3RS score of

≥64); DSM-IV TR: Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-IV- Text Revision. |

Discussion

In the present study, the diagnostic accuracy for

INDT-ADHD for ADHD was high irrespective of age and gender. Sensitivity,

specificity, positive predictive and negative predictive values were

acceptable INDT-ADHD performed well in differentiating ADHD from normal

children but could not effectively differentiate it from other NDD’s,

especially ASD.

Content validity refers to the extent to which a

measure represents all facets of a given construct. In this tool it was

inattention, hyperactivity, restlessness and distractibility. This was

ensured during tool development as only those items in which >50%

consensus was reached by the experts were considered. During validation

this was substantiated as not a single item was assigned a score of ‘0’

in > 50% of children with ADHD by expert diagnosis. Construct validity

is the degree to which a test measures what it claims to be measuring

that is assessed by factor analysis of the symptom clusters of ADHD.

Variability in factor analysis results has been observed in studies with

2-factor, 3-factor and 4-factor structures being used to explain the

construct, probably attributable to differences in study population and

statistical approach [15-17]. The 4-factor structure of INDT-ADHD is

similar to the model offered by Baumgaertel, et al. [17].

Moderate convergence of INDT-ADHD with C3PS implied that the construct

of both were theoretically related to each other. The Cronbach’s alpha

coefficient of internal consistency is in agreement with a previous

study [18].

The strength of this study was its multi-centric

development and validation. Using appropriateness criteria as diagnostic

tool has been successful previously [19]. However, validation was on a

referral center based population where the prevalence of ADHD is

expected to be high, and not representative of the general population.

The total variance explained by the 4-factor model of 60% indicates that

it could be due to missing information in the tool or a small sample

size. The former may reflect absence of inclusion of symptoms of

co-morbid disorders whereas in the latter a larger size may generate a

more stable factor structure model and improve construct validity.

The implication of this study is the creation of

qualitatively-derived and theory-guided appropriate-ness criteria-based

tool for diagnosing ADHD with high accuracy, and adequate validity and

internal consistency. It can be used for initial evaluation and

assessment of post-intervention status in ADHD. Currently available

tools for diagnosing ADHD are patented and need payment every time these

are used. The INDT-ADHD will be available in public domain and is likely

to expand diagnostic access to populations in developing countries.

Contributors: All authors have contributed,

designed and approved the study. NKA will act as a guarantor for this

work.

Funding: Ministry of Social Justice and

Empowerment (National Trust), National Institute of Health (NIH-USA);

Fogarty International Center (FIH), Autism Speaks (USA); Competing

interests: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Diagnosis of ADHD

necessitates evaluation by an experienced psychologist,

psychiatrist, or developmental pediatrician.

What This Study Adds?

• The INDT-ADHD diagnostic tool for ADHD is

a freely available tool, developed for the resource limited

settings through expert consensus based on established DSM-IV-TR

criteria.

|

References

1. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J,

Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and

metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007; 164:942-8.

2. Srinath S, Girimaji SC, Gururaj G, Seshadri S,

Subbakrishna DK, Bhola P, et al. Epidemiological study of child

and adolescent psychiatric disorders in urban and rural areas of

Bangalore. Indian J Med Res. 2005; 122:67-79.

3. National Institutes of Health Consensus

Development Conference Statement: Diagnosis and treatment of

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 2000; 39:182-93.

4. World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10

Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria

for Research. Geneva: WHO; 1993.

5. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed., text rev.

DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6. Dulcan M. Practice parameter for the use of

stimulant medication in the treatment of children, adolescents, and

adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997; 36:85-121.

7. Howitt D, Cramer D. First Steps in Research and

Statistics: A Practical Workbook for Psychology Students. London:

Routledge; 2000.

8. Ullman RK, Sleator EK, Sprague RL. ACTeRS: Teacher

and Parent Forms Manual. Champaign, IL: Meri Tech, Inc; 1997,

9. Wolraich ML, Feurer I, Hannah JN, Pinnock TY,

Baumgaertel A. Obtaining systematic teacher report of disruptive

behavior disorders utilizing DSM-IV. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;

26:141-52.

10. Conners CK, Sitarenios G, James D, Parker A,

Epstein JN. Revision and restandardization of the Conners Teacher Rating

Scale (CTRS-R): Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J

Abnormal Child Psychol. 1998; 26:279-91.

11. Conners CK. Conners’ Parent Rating

Scales-Revised. New York, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1997.

12. Swanson J, Nolan W, Pelham, WE. SNAP rating

scale. Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC); 1982.

13. Adesman AR. The Attention Deficit Disorders

Evaluation Scale. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1991; 12:65-6.

14. Conners CK. Conners’ Rating Scales, 3rd Edition.

North Tonawanda: NY Multi-Health Systems; 2008.

15. Kanbayashi Y, Nakata Y, Fujii K, Kita M, Wada K.

ADHD-related behavior among non- referred children: parents’ ratings of

DSM-IIIR symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 1994; 25:13-29.

16. Baeyens D, Van DL, Danckaerts M. Validity of the

DSM-IV factor structure of ADHD in young adults. International

Eunethydis Meeting, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The Netherlands 26-28

May 2010

17. Baumgaertel A, Wolraich ML, Dietrich M.

Comparison of diagnostic criteria for attention deficit disorders in a

German elementary school sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

1995; 34:629-38.

18. Mitsis EM, McKay KE, Schulz KP, Newcorn JH,

Halperin JM. Parent–teacher concordance for DSM–IV

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a clinic-referred sample. J

Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000; 39:308-13.

19. de Bosset V, Froehlich F, Rey JP, Thorens J,

Schneider C, Wietlisbach V, et al. Do explicit appropriateness

criteria enhance the diagnostic yield of colonoscopy? Endoscopy. 2002;

34:360-8.

|

|

|

|

|