Hematopoetic, hepatic and dermatological toxicity of

Carbamazepine is well-known, but cardiac side-effects are

not that widely recognized. Its use has rarely been reported

to cause conduction abnormalities, predominantly in elderly

women, with therapeutic (or moderately elevated) plasma

concentrations of the drug [1]. We herein report a child

with syncopal attacks following carbamazepine use.

An 8-year-old child presented with

history of fainting attacks while playing, which lasted for

a few seconds, followed by spontaneous recovery. He had two

such witnessed episodes in the preceding week, which

prompted the present consultation. He was developing

normally, studied in class III, and never had any previous

episodes of dizziness, syncope, breathlessness or cyanosis.

He did not report any other associated cardiac symptoms. He

was on regular treatment with carbamazepine (15 mg/kg/d) for

Idiopathic generalized epilepsy from another institution

since past one year, with no non-compliance, or missing a

dose in the last 24-hours. Contrast-enhanced CT head done at

that time was normal.

On detailed history, these episodes of

fainting did not resemble the seizures that he had

experienced in the past, and during this episode he did not

have any other neurologic symptoms. The fainting attacks

were transient and the child recovered immediately after the

fall. On examination, the patient was alert and cooperative

with blood pressure of 98/76 mmHg. He was noted to have an

irregularly irregular pulse, and ectopic heart beats after

every 8 to 10 beats, with a heart rate of 70 to 80 beats per

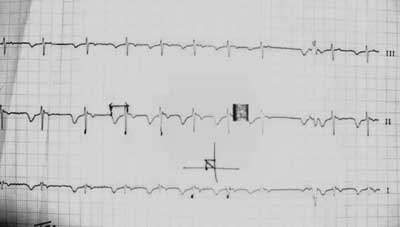

minute. A 12-lead electrocardiogram showed ventricular

premature beats (Fig. 1). Child was admitted

and started on tablet atenolol, 25 mg daily . An

echocardiogram ruled out structural heart disease. Holter

monitoring for 24 hours showed frequent ventricular ectopic

beats though the child did not have further fainting

episodes during the hospital stay.

|

|

Fig. 1 Ventricular

premature beats seen in the child’s

electrocardiogram on admission.

|

In the background of reports of

carbamazepine causing conduction disturbances, it was

replaced with tablet valproate 15 mg/kg/day. Atenolol was

stopped. Serum carbamazepine level six hour after the last

dose of the drug was 10.6 µg/mL (therapeutic range 8-12 µg/mL).

The patient was discharged on day 5, after documenting a

normal ECG. Repeat holter study at 3 months of follow-up,

did not show any abnormality. On follow-up at one year, he

was asymptomatic without any complaints of fainting attacks

or giddiness.

Carbamazepine exerts its effect by acting

as a sodium channel blocker, and is known to produce

negative chronotropic and dromotropic effects on the heart;

thus, it may sometimes lead to conduction disturbances,

including Sinus bradycardias, sinus pauses, junctional

bradycardias, and AV blocks, ranging from first degree to

complete [2]. A recent review of these reports

showed that elderly women, particularly those with a

pre-existing conduction abnormality, were mostly involved

[1], though reports in young also exist. Usually brady-arrhythmias

occur at therapeutic doses, whereas sinus tachycardia is the

main arrhythmia in massive CBZ overdose [3]. An increase in

ventricular premature beats over next five days has also

been reported in patients who abruptly discontinued CBZ

because of cardiac side-effects [4]. Our patient, however,

did not have any history of discontinuation of the drug

prior to presentation. Another possibility could have been

arrhythmia-related seizures [5]; however, there was no

recurrence of the ECG abnormality after stopping

carbamazepine. Using the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction

Probability Scale classified the event as a ‘possible’

adverse drug reaction.

We wish to highlight that cardiac

side-effects may sometimes occur after prolonged

carbamazepine therapy, and may be associated with normal or

slightly high serum levels. As seen in this child, rapid

resolution of symptoms occurs on discontinuing the drug.

1. Hewetson KA, Ritch AE, Watson RD. Sick

sinus syndrome aggravated by carbamazepine therapy for

epilepsy. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:497-8.

2. Tomson T, Kenneback G. Arrhythmia,

heart rate variability, and antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia.

1997; 38:S48-51.

3. Kasarskis EJ, Berger R, Nelson KR.

Carbamazepine-induced cardiac dysfunction. Characterization

of two distinct syndromes. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:186-91.

4. Kennebäck G, Ericson M, Tomson T,

Bergfeldt L. Changes in arrhythmia profile and heart rate

variability during abrupt withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs.

Implications for sudden death. Seizure. 1997;6:369-75.

5. Venugopalan P, Al-Anqoudi ZA, Al-Maamari WS. A child

with supraventricular tachycardia and convulsions. Ann Trop

Paediatr. 2003;23:79-82.