Pediatricians are the professionals most concerned

about the well-being of the child, in addition to being a respected group

in the society. They are often the first contact of a child who has

suffered abuse. In the outpatient or casualty, whenever one comes across a

case of child abuse, chances are that the severity may often determine

whether we do suspect it or fail to recognize the subtle varieties. The

pediatrician can only recognize all such cases, when he/she considers

every child seen by him/her potentially at risk of either abuse or

neglect. Multiple studies worldwide have demonstrated that health workers

have insufficient knowledge and/or training in addressing child abuse. The

NSCA(2) also recommends that ‘good practices in protection need to be

documented/ shared for qualitative improvement at all levels’.

The Child Rights and Protection Program (CRPP), taken

up under VISION 2007 program of Indian Academy of Pediatrics, stems from

the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)(3), and

is a major step in the history of Child Rights in India. It aims to

provide an impetus to the involvement of pediatricians in child protection

activities. As part of the CRPP, a ‘Training of Trainers (TOT) Workshop on

Child Rights and Protection’ was held on 10th and 11th January, 2007 in

Mumbai (under the aegis of Pedicon 2007, Department of Pediatrics,

LTMG Hospital, Sion, Mumbai; The Royal College of Pediatrics and Child

Health; and, Northumbria Healthcare Trust, UK). The recommendations at the

end of the workshop included: developing country-specific teaching and

training manual, to organize methodology workshop for TOT, and, formation

of Task force of IAP CRPP Programme. This task force developed a

module for ‘Training of Trainers Workshops for Pediatricians’. RCPCH

shared their protocol on ‘Response to child abuse’(4,5) and gave

permission to modify it in the Indian context. A National Consultative

Meet was held on 10th and 11th October, 2007 at New Delhi to discuss and

approve the abovementioned teaching program. Participants included

pediatricians from all parts of the country, as well as, all members of

the ‘task force’ [Annexure 1]. The program was discussed and

ratified at the meet.

Recommendations

Who is a child?

Most of the Government programs on children are still

targeted for the age group below 14 years. The UNCRC, 1989(3) defined the

child as "every human being below the age of eighteen years unless,

under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier. After

the introduction of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) Act, 2000

(amended 2006), for all practical purposes, a child is considered as a

person below 18 years.

Recognizing child abuse

Interviewing the child with abuse

A large proportion of children encounter abuse in their

homes itself(3). Most cases of child abuse are committed by people known

to the child and most children do not report the matter to anybody. When

abuse is suspected, the concerned doctor must try to gather a detailed

medical history from the child, if possible, and the caretakers. During

the interview process, the following points need to be considered:

• If possible, interview the child alone (separately

from the attendants).

• The interviewer must be sensitive to the child’s

possible fears and apprehension when discussing the home situation and

should tailor the interview to the child’s developmental level.

• Repetitive interviews can be problematic to the

child. The doctor concerned must gather the basic information necessary

to help make the decisions that are in best interest of the child.

• In cases of severe abuse, parents may flee with the

child, and thus it is advisable to report the case to the authorities,

prior to informing the parents of the suspected diagnosis.

• Documentation of the interview results is

essential.

• Above all, everything is to be done in the best

interest of the child.

Maintaining a professional approach with the family,

although not always easy, can facilitate the interviewing process.

Explaining the reporting process and what the parents can expect to happen

is often helpful. Non-accusatory statements should be used. The various

techniques and stages on interviewing a child with abuse are available

elsewhere(4-8).

Response of the pediatrician to child abuse

A pediatrician’s response to a case of child abuse,

either in the outpatient or inpatient settings should follow three

cardinal principles. It should be:

1. Child centered and child friendly: It

should keep the best interest of child in mind. Safety of the child is

to be considered paramount.

2. Family supportive: Response should provide

adequate support to the family as generally family forms the backbone of

the child protection system. Keeping the child permanently in an

institution is the last option in child protection.

3. According to the law of the land and safe for

the pediatrician: The management and documentation of the case

should be impeccable to avoid professional litigation later.

When a pediatrician is confronted with a suspected case

of child abuse, it is important not to jump to the diagnosis of abuse. The

basic rules to be followed include:

• To consult widely with people who know the child

well, like relatives, teachers etc., apart from parents.

• To gather information from other professionals like

the child’s regular pediatrician, the parents’ physician, especially if

the parent is suffering from mental disease, drug abuse, or other

chronic diseases.

• To check past medical records for any hospital

admissions (for child safety concerns) and developmental history.

• To document child safety concerns after a

comprehensive medical assessment.

• To make a final conclusion after discussing the

case with seniors, peers, psychologists and probably even NGOs and

social worker.

The responses of a pediatrician to a child abuse case

can be broadly classified into:

1. Urgent response is needed if the child is

brought dead or with a life threatening injury or with acute sexual

assault (reports within 24-72 hours of the abuse). The child will need

emergency care and the police would require immediate forensic samples

to book a strong case against the abuser. Such cases are best managed in

a government hospital setting.

2. Admission to the hospital is needed in all

cases of serious injuries. A child may be admitted incase it is felt

that there is an immediate threat to his safety at home.

3. Social Services like Child Welfare

Committee (CWC) and Child Helpline (Phone No.1098) or local NGOs may be

contacted if the parents refuse to follow the treatment plan or if there

is an immediate threat to safety of other sibs. CWC and Child Helpline

can also be contacted in any case where child rights are violated like

neglect, child labor, corporal punishment at school, child marriage etc.

4. Planned response is the best. Here a

planned interview and examination are performed in a child-friendly

atmosphere with the appropriate equipment and health personnel (social

worker, psychologist, gynecologist if needed). A child friendly

atmosphere is one that is sensitive to the needs of the child, where he

feels comfortable, relaxed and at ease to confide his problems.

Reporting Child Abuse

The following background information is important

before the pediatrician decides to handle a case of child abuse or

neglect:

Childline. This service, launched by the Government

of India, is a 24-hours free phone service, which can be accessed by a

child in distress or an adult on his behalf by dialing the number 1098 on

telephone. Childline provides emergency assistance to a child and

subsequently based upon the child’s need, the child is referred to an

appropriate organization for long-term follow up and care. It responds to

calls for medical assistance, shelter, repatriation, missing children,

protection from abuse, emotional support and guidance, information and

referral to services, death related calls etc.

Child Welfare Committee. Under the JJ Act, it is

possible for the Child Welfare Committee to declare any parent or

guardian; who grossly abuses a child, or fails to protect a child from

being abused, as unfit persons and order for the removal of the child from

the custody of such persons. The offences under this Act are cognizable

and the special police officer or any of his subordinate may arrest a

person without warrant and search the premises without warrant.

Mandatory reporting. Mandatory reporting mandates

certain professionals to report to appropriate authorities suspected cases

of child physical and sexual abuse. Designated professionals (including

pediatricians) are required by law to report all suspected cases of child

abuse and neglect. They are protected by law in case of an erroneous

reporting, as long as it was in good faith. They are legally penalized in

case they fail to report. Under this law, proof is not required to report,

and the only requirement is to report suspected abuse. In India, such

provisions have not yet been introduced.

Whom to Report. In the absence of ‘mandatory

reporting’ provisions and child protection services in India, this

constitutes an important decision. Usually the reporting can be done to

the Police, the local Child Welfare Committee, and even to the

Childline. However, even after reporting, networking among various

professionals is usually required to follow-up the case to its just

conclusion.

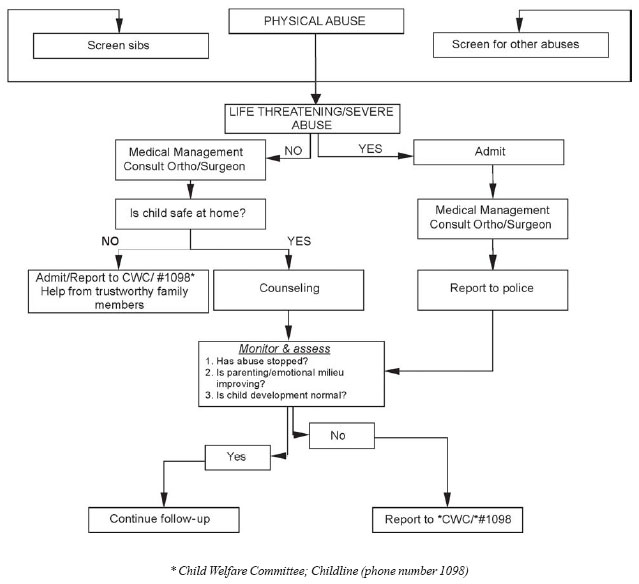

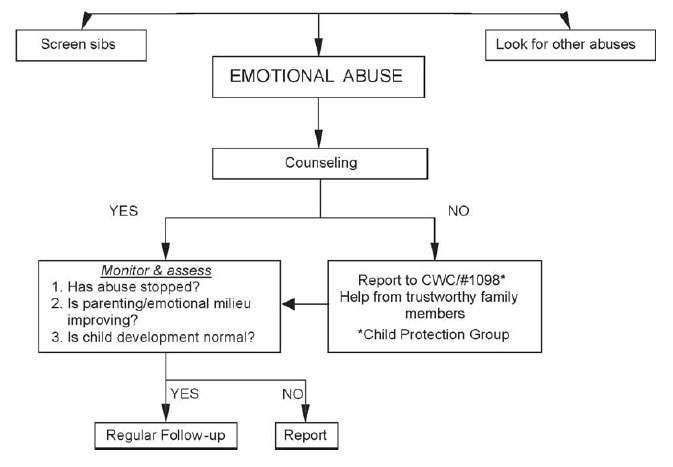

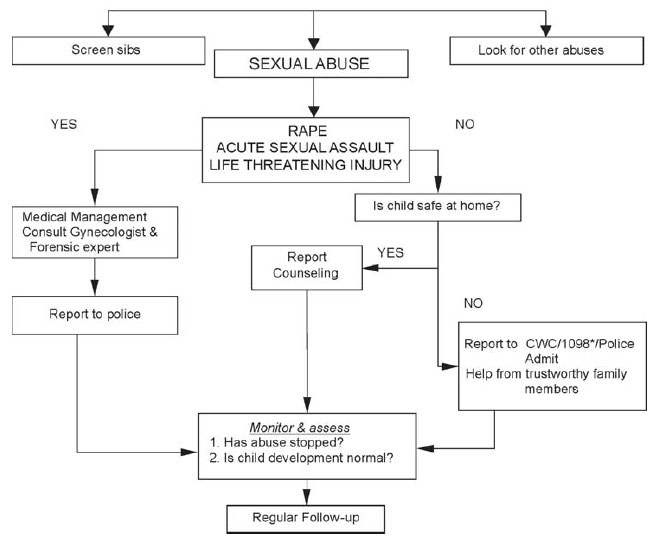

The team developed the following flow charts, based on

our discussions and on previously published material(4,5,15), which

provide suggested protocols for pediatricians to respond to physical (Fig.

1), sexual (Fig. 2), and emotional abuse (Fig.

3). Following are the important goals of a pediatrician’s response:

1. Immediate goal is to ensure safety and provide

emergency care if needed.

2. Comprehensive medical assessment including

history, examination and investigations, and documentation.

3. Short term goals include providing immediate

emotional (counseling) and social support to the child and family and

treating physical problems like injuries, providing immunization, STD

prophylaxis and emergency contraception.

4. Long term goals include complete physical and

psychosocial well being of the child. They also ensure his reintegration

into the family and social system.

|

|

Fig. 1 Response to physical abuse. |

|

|

Fig. 2 Response to emotional abuse. |

|

|

Fig. 3 Response to sexual abuse. |

Comprehensive Medical management

History

1. A detailed account of the incident(s) should be

sought from both the caregiver and the child, separately. History should

be recorded verbatim. The rapport building and interviewing skills of

the examiner are of utmost importance. The examiner should observe the

behavior of the child during history-taking.

2. Presenting symptoms of the child are noted.

Physical, mental and personality development should be noted.

3. Family and Social history should be taken with

details about the marital status of parents, whether the family is a

broken or dysfunctional one, total number of members in the family,

interpersonal conflicts and social interaction among various family

members, etc.

4. Social history includes employment details of

parents, their age, education and physical and mental maturity, nature

of parent-child relationship, any concerns about profession, health,

education, etc.

5. Sexual history of victim about exploitation or

abuse should be obtained. Presence of addictions such as alcohol, drugs

and tobacco should be noted. The recorded information should include the

relation of the victim with the accused and exploiter, age difference of

accused and victim and other relevant information.

The presence of a chaperone, preferably a nurse is a

must during the assessment. The assessment should be recorded in a special

proforma. History-taking from the parent or caretaker should be documented

separately from that of the child. Repeated interviews are to be avoided.

• It is important to treat the child and the parents

with respect and dignity without making accusations.

• Listen carefully and have a sensitive, empathic and

nonjudgmental attitude.

• Ask open-ended and non-leading questions.

• Nonverbal cues as ‘watchful frozenness’, sad mood,

avoidance of eye contact, etc. should be recorded. Exact question and

answers need to be recorded verbatim.

• Points to be covered in history include place,

time, witness, present and past history, noticeable behavior change,

developmental and immunization history. Family history, pedigree chart

and social history are extremely important. A psychosocial history known

by the acronym HEEADDSS (details of home, education, eating behavior,

activities and peers, drugs, depression, suicide, sexual history and

sleep pattern) can be taken directly from an adolescent patient.

Examination

Examination of victims of abuse and neglect follows the

same basic principles as examination for any other medical condition, but

requires an expertise which accrues from training and regular updating.

There are many standard works on the examination of the abused

child(4,5,8-10), where a detailed discussion is available. Parental and

(preferably) the child’s consent are essential for a medical examination.

The child may prefer to get examined by a doctor of the same sex. He may

also choose to have a trustworthy adult along with him during the

procedure. The pediatrician may seek the expertise of a forensic physician

and a gynecologist (for a female child) while examining a case of sexual

abuse. The following should be recorded:

• Resistance to examination, especially in a case of

sexual abuse and/or, dissociation (going to sleep during examination)

• General demeanor (like unkempt appearance in

neglect)

• Vitals and head-to-toe general physical

examination, especially noting pallor, bruises, vitamin deficiencies

(and malnutrition), sequelae of unexplained trauma, etc.

• Height, weight and head circumference to be plotted

on growth chart

• Sexual Maturity Rating for adolescents

• All injuries are to be marked on anatomical

diagrams. Special sites to look for injuries include ears, inside the

mouth, soles, genitalia and anus.

• Systemic examination is done, especially to look

for injuries.

• Examination of genitalia in girls should be done in

supine (frog leg), prone (knee chest) and left lateral position. Details

of hymen and injuries are to be noted. Anal dilatation on per rectal

examination may indicate sodomy, and must be documented. Presence of

discharge, genital ulcers, warts and inguinal lymphadenopathy are to be

noted and, samples preserved in appropriate manner for forensic

evaluation.

It is important to know that in 70-85% of documented

sexual abuse, the physical examination is normal.

Investigations

The correct age of the child should be established for

any case that is going to be reported and is a must in case of a

trafficked child. Other investigations which need to be done:

• Child sexual abuse: STD screening, including low

and high vaginal (in post pubertal girls) swabs and urethral swabs in

boys, and serology for HIV, hepatitis B and syphilis are done in cases

of acute sexual assault, penetrative abuse, vaginal/ urethral discharge

and, STD in abuser. Pregnancy test should be done in an adolescent girl.

Forensic samples maintaining the chain of evidence include skin, hair,

nail clippings, clothing, saliva, and, oral and genitourinary secretions

in acute sexual assault(11).

• Physical abuse: Skeletal survey is done in a case

of multiple injuries, and in all cases if a child is below 2 years.

Multiple bruising entails a detailed hematological profile, including

bleeding and coagulation profile. Neuroimaging and ultrasonography of

abdomen are indicated in a case of head and abdominal injury,

respectively.

Management

Management should be child friendly and should aim at

achieving the short term and long term goals. The current and future plans

of action should be discussed with the non-offending family members. The

need for breaking immediate contact with the abuser, if he/she is a known

person, should be emphasized.

The physical injuries should be treated. Hepatitis B

vaccination should be considered if the sexually abused child is not

vaccinated, and if the child presents within six weeks of the last assault

(schedule 0, 1, 2, 12)(12). DPT/ DT vaccination should be given in

unvaccinated children. Tetanus immunization status should be confirmed and

updated, if necessary. Overall, the risk of acquiring a STD is low and

varies according to many factors(13). STD prophylaxis and emergency

contraception is to be given to an adolescent with acute sexual assault.

STD prophylaxis should be offered in cases of oral-genital,

genital-genital, or anal-genital contact by the abuser. HIV prophylaxis

may be indicated in specific cases(12,13); it should be considered for

every case that presents within 72 hours of the most recent abuse, if

unprotected anogenital penetration has occurred, taking into consideration

risk factors(12). All children of the family should be screened for abuse

if the abuser is close to the family. Multiple types of abuses may coexist

in the same patient and should be specifically looked for and managed.

Injuries should be treated as needed. Lacerations extending into the

vagina are not common and should be assessed by a gynecologist, as the

full extent of the laceration must be determined. The vaginal wall is

extremely thin in the prepubescent child and may be perforated more easily

than in the older child(13).

Counseling of the child and family forms the

cornerstone of the management. The immediate counseling of the child that

can be done by the pediatrician should focus on the following:

• Believe the child, reassure and absolve feelings

of guilt/ blame

• Explain about the existence of a medical, family

and social support system.

• Listen carefully to all fears and concerns

associated with disclosure.

• Teach coping and assertive skills.

Referrals to appropriate specialties should be made

according to the need of the child. These will include psychologist,

psychiatrist, orthopedic surgeon, surgeon, social services and police. The

family members may also need counseling and treatment from mental health

professionals.

Follow up

Follow up after 2 weeks, or earlier if necessary, is

essential to reassess the child and evaluate for development of sequelae.

In acute sexual assault of an adolescent girl, a repeat pregnancy test is

warranted. A repeat serology for syphilis at 4-6 weeks and for HIV at 3-6

months is required.

The long term after-effects of abuse on the physical

and mental health are well known, but some children suffer no adverse

consequences. The outcome is influenced by the following factors: nature,

extent and type of abuse, age of child, temperament and resilience of the

child, relationship of abuser to the child, and family’s response to abuse

and medical management. A single episode of non-contact sexual abuse by a

stranger may just need reassurance and letting out feelings in one or two

counseling sessions with a good outcome. But prolonged abuse by a close

family member will require longer and multiple counseling sessions to heal

completely.

Regular follow up of the abused children should include

the following: To verify if abuse has stopped, to monitor physical and

mental health, To monitor development and ensure that it is normal, and to

refer for therapy (counseling, cognitive behavior therapy or medication)

for delayed presentation of symptoms.

The key points to be kept in mind while making

decisions in the existing framework of child protection services include:

1. Seriousness of abuse: Serious abuse requires

urgent intervention and long term follow up

2. Safety of the child: If the child is not safe at

home, help from non-offending family members for a change in residence

is sought for. CWC, Child Helpline and local NGOs may also help in this

situation. If the home continues to be unsafe, safer options like foster

care and adoption of the child need to be considered.

3. Importance of counseling and follow up of the

child are important issues. Counseling of the parents, if they are the

abusers, is also necessary. All abuse, especially sexual abuse, needs to

be reported to the police.

The pediatrician’s response must always be in

accordance with the existing law of the country, as highlighted in these

guidelines.

Medico-legal aspects, Documentation and Reporting

Most victims of obvious child abuse are directly

brought to hospitals (usually Government hospitals) for medical

examination by the police. They may be accompanied by Social worker (NGO),

but at times are brought by parents / guardians. At other times, there may

be incidental recognition of child abuse during consultation for an

unrelated medical problem, which can occur in any type of setting.

Guidelines are available for documentation and may be used or adapted

depending on local settings(11).

All consultations with the patient should be in hand

written notes, with diagrams, body charts, and if possible, photographic

documentation. It should be understood that both, age determination and

complete examination requires multidisciplinary references. Their opinions

either in person or telephonically, should be recorded. Time, date,

signature, designation and additional comments, wherever appropriate, are

a must for enabling the due process of law.

The examining doctor should make sure that important

details are not omitted. All aspects of consultation should be documented

and detailed notes must be made during the consultation, patient’s records

have to be kept strictly confidential and stored securely. The

documentation should be confined to areas of health care expertise only;

interpretation of the same has to be done by a trained person if the

examining Medical Officer is not trained in examination of medicolegal

cases. Consent should always be taken in writing, and preferably from both

the guardian and the victim. All documents should be preserved for, as

yet, an undetermined amount of time.

Steps of medical examination

• Documentation should be accurate, impartial,

objective and scientific.

• After obtaining written consent, the preliminary

data should be noted including the FIR No., date and time and place of

examination, witnesses present during examination and recording, details

of informant and relation with the child.

• Demographic information, brief History and an

account of Assault should be taken.

• Examination of clothes of victim for semen stains,

struggle tears, trace material etc. should be done.

• Genitalia examination and photography (if needed)

should be taken.

• Findings of general physical examination, systemic

examination, exam for injuries, clinical/ forensic (STD, pregnancy, etc)

should be recorded.

• Examination for age determination (if needed) is a

must in a trafficking case. Age determination involves multidisciplinary

approach. The age range provided should be as narrow as possible.

The examining doctor must express opinion about

physical/sexual abuse/age determination. Treatment should be administered,

as per need. The examining doctor should be liberal in taking second

opinion, and taking references from specialists in other faculties, as

required.

Reporting by medical officer

The medical officer should not try to be an

investigator. His duty is to the court and not to either party.

1. The report should be written clearly and precisely

and should state clearly fact and medical opinion. The Court relies on

objectivity, competence and integrity. Hence the medical officer should

be balanced and accurate, report without exaggerations, and limit the

report to facts.

2. The opinion must have components of injury, sexual

activity and age estimation if required, and must consider whether there

is sexual abuse or not, acute and chronic effect on victims body and

mind, and whether proper samples have been collected for identification.

3. Positives and negatives should be included in the

report. The medical officer should not mislead by omission and should

avoid making generalizations.

4. Age determination is a must in trafficking cases.

5. The report should be reviewed and, if necessary, a

peer review should be obtained before handing it over. Premature opinion

should not be given.

Media and Child Abuse

The fundamental guideline for the media with regard to

reporting on child abuse is to protect the identity of the child. The JJ

Act, 2000; the Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, 1956; and, the Criminal

Procedure Code prohibit the disclosing of the identity of victims. Press

Council Act has also laid down the norms to be followed by the media,

keeping in mind the rights of children.

Advise to Caregivers of an Abused Child

If a child discloses that he/she has been sexually

abused or exploited:

· Support the child and explain that he/she is not

responsible for what happened.

• Believe the child and don’t make her/him feel

guilty about the abuse.

• Be empathetic, understanding and supportive.

• Consult a doctor and consider the need for

counseling or therapy for the child.

• Don’t criticize the child or get angry with

her/him.

• Don’t panic or overreact, with your help and

support, the child can make it through this difficult time.

• Don’t ignore the abuse. Voice your fears to

responsible NGOs or individuals.

• Lodge a complaint with the police and ensure that

the abuse stops immediately.

Guardians should be made to understand that their first

responsibility is to the child – to protect him/her and to ensure that

there is no breach of privacy or confidentiality.

Conclusions

These guidelines detail suggested actions to be taken

after suspecting child abuse and neglect. Many of the details of

examination and interviewing are already available in standard texts and

have not been detailed here. We plan to review the guidelines as and when

further changes in the laws dealing with age of child and, child abuse and

neglect occur.

Acknowledgments

The IAP Child Rights and Protection Program was

launched by Dr Naveen Thacker during his tenure as IAP President 2007. We

are thankful to Dr U. Bodhankar, chairperson of the initial ToT at Mumbai.

We acknowledge the support of – Dr Michael Webb, RCPCH Overseas Director

(South Asia), Department of Paediatrics, Gloucestershire Royal Hospital,

Gloucester, UK: for permission to adapt the RCPCH training material by

modifying it in the Indian context; Dr Neela Shabde, Consultant

Pediatrician and lead for RCPCH Safeguarding Children Level 2 Project, UK:

for helping us to adapt the material in the Indian context; Ms Victoria

Rialp, Chief, Child Protection, UNICEF: for the support of UNICEF to fund

this project; Dr Loveleen Kacker, Joint Secretary, Child Welfare, Ministry

of Women and Child Development and, Mrs Shantha Sinha, Chairperson,

National Commission for Protection of Child Rights: for their support. We

also acknowledge the help received from the invited experts: Rajeev

Awasthi, Criminal lawyer, Delhi, and Dr Gaurav Agarwal, Department of

Forensic Medicine, Safdarjung Hospital, Delhi.

1. Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse

Prevention, 29-31 March 1999, WHO, Geneva. Geneva, World Health

Organization, 1999 (document WHO/HSC/PVI/99.1). Available from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/aaa00302.pdf.

Accessed on 22 November, 2009.

2. Study on Child Abuse: India 2007. Ministry of Women

& Child Development, Government of India, Delhi, 2007. Available from

http://wcd.nic.in/childabuse.pdf. Accessed on 21 November, 2009.

3. Convention on the Rights of the Child. United

Nations Children’s Fund. Delhi, 2004.

4. Child Protection Companion. 1st Edition, RCPCH,

London, 2006. Available on http:// www.rcpch.ac.uk/Education/Education-Courses-and-Programmes/Safeguarding-Children.

Accessed on 21 November, 2009.

5. Child Protection Reader. 1st edition, RCPCH, London,

2007. Available on http:// www.rcpch.ac.uk/Education/Education-Courses-and-Programmes/Safeguarding-Children.

Accessed on 21 November, 2009.

6. Agarwal K, Dalwai S, Galagali P, Mishra D, Prasad C,

Thadani A. Manual on recognition and response to child abuse-the Indian

scenario. Indian Academy of Pediatrics - Child Rights and Protection

Programme (CRPP), Delhi, 2007.

7. Safeguarding children: Recognition and response in

child protection. RCPCH Trainer CD ROM, 2006, London, 1st edition.

8. DGH de Silva, CJ Hobbs. Managing Child Abuse. A

Handbook for Medical Officers. WHO SEARO, Delhi, 2004.

9. Kellog N. Evaluation of suspected child abuse and

neglect. AAP Policy statement. Pediatrics 2007; 119: 1232-1241.

10. Kellog N. Evaluation of sexual abuse in children.

AAP Policy statement. Pediatrics 2005; 116: 506-512.

11. Manual for Medical Officers. Dealing with Child

Victims of Trafficking and Commercial Sexual Exploitation. Department of

Women and Child Development, Government of India, New Delhi, 2007.

Available from URL: http://wcd.nic.in/ManualMedicalOfficers.pdf. Accessed

on 21 November, 2009.

12. The Physical Signs of Child Sexual Abuse – An

Evidence-based Review and Guidance for Best Practice. Royal College of

Paediatrics and Child Health, London, 2008.p.146-147. Also available from

URL: http://www.rcpch.ac.uk/Research/CE/RCPCH-guidelines.

13. American Academy of Pediatrics. Sexually

transmitted infections in adolescents and children. In: Pickering

LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, McMillan JA, eds. Red Book: 2006 Report of the

Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL:

American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006.p. 166-177.

14. Resource Book. First National Conference on Child

Abuse for Multidisciplinary Professionals (COCAMP 2004). Indian Council

for Child Welfare, Tamil Nadu and Sri Ramchandra Medical College and

Research Institute, Chennai: February 2004.

15. CJ Hobbs, JM Wynne, HGI Hanks. Child abuse and

social aspects of pediatrics. In: N McIntosh, PJ Helms, RL Smyth,

Eds. Forfar and Arneil’s Textbook of Pediatrics, 6