The novel

coronavirus (SAR-CoV-2) pandemic has disrupted

medical education worldwide [1]. Most of the medical

schools have quickly adapted to the online classes

with shifting of live clinical exposure with the

virtual one. Some schools also echoed concerns over

clinical clerkships and assessment during these

times. The COVID-19 pandemic represents a

transformation in medicine with the advancement of

telehealth, adaptive research protocols, and

clinical trials with flexible approaches to achieve

solutions [2-4]. We herein share our early initial

experience of online training of medical students in

the setting of COVID-19.

In wake of impending restrictions, we explored

available options for online classes and adopted G

Suite for Education using Google Classroom coupled

with Google Meet for Video-conferencing (https://edu.google.com/products/gsuite-for-education/?modal_active=none).

A schedule was made and messages were sent to

students by email and short messaging service (SMS)

to join their respective classes. An orientation

program was conducted to familiarize the faculty to

this platform. A team of trained faculty members was

deputed at the lecture venues to assist and

troubleshoot technical issues, if any. Additionally,

training videos were shared with faculty members.

In order to minimize excessive data usage by

students and preventing high screen time, a

four-hour teaching schedule, ensuring a judicious

mix of lectures and practical demonstrations/case

discussions were employed with a break of 10-15

minutes between sessions. To promote student

engagement, and to closely replicate laboratory and

clinical environment, short videos on lab procedure

and case based clinical examination were prepared

and shared on the virtual classroom. To make the

session interactive, students were encouraged to use

chat-box and switch on their microphones, wherever

feasible. Assignments were administered through

inbuilt plugins.

A questionnaire was prepared and administered via

Google forms to the students belonging to different

semesters of the MBBS course. The questionnaire was

reviewed and validated by the involved faculty

members. Participation was voluntary and complete

anonymity was ensured. Data was compiled using

spreadsheets. Gaussian fit of data was assessed

using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

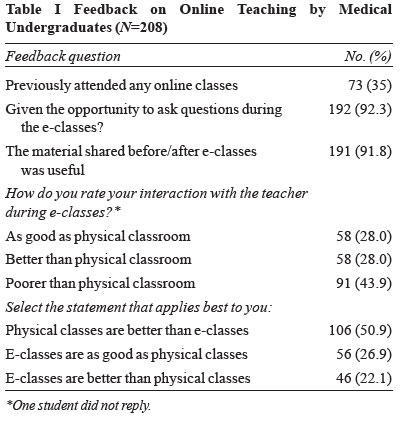

Across four batches from second to eighth semester,

398 medical undergraduate students were enrolled in

the classes; 208 provided their responses to the

questionnaire, with similar proportion across

various semesters (44-61%). The detailed responses

are depicted in Table I. The students,

based on their quantitative (Fig. 1)

and qualitative feedback, appreciated the online

platform. Large number of students had not attended

any online classes previously. Majority of the

students stated that they were given the opportunity

to ask questions (92.3%). They believed their

interaction with the teacher was better than (27%)

or as good as (27.8%) that during physical

classroom. The responses across semesters were also

uniformly similar.

|

| |

| |

|

|

Number of students in II, IV, VI and VIII

semesters was 61,47,44 and 56, respectively. |

Fig. 1

Rating of online classes during COVID-19

pandemic by medical graduates of different

semesters on a Likert scale of 1-10.

|

Interestingly, innovative solutions have emerged

whenever such problems have set in during SARS and

MRES outbreaks using telephone and virtual

environ-ment [5,6], and other adaptations during

COVID-19 [7]. While Moszkowicz, et al. [8]

implemented Google Hangouts for a similar purpose

but with only 10 students, we conducted concurrent

sessions for a large number belonging to four

different semesters. Our platform also supported

flipped classroom to some extent by providing

learning material in advance and promoting student

discussion during online sessions [9].

Student feedback revealed some interesting paradox.

While appreciative of the platform, nearly 50% of

the students still believed that physical classroom

was better than e-classroom. However, the reasons

for this perception could not be assessed. The study

was based on a small sample of students who have

anonymously volunteered to provide feedback.

Secondly, we had very short time to implement and

hence a well-structured training program for faculty

could not be done. This was; however, circumvented

to some extent, by the ease and self-explanatory

nature of the platform, a short explanatory video

and provision of technical support at lecture

venues. Furthermore, majority of our teachers got

adapted to this forum after taking a couple of

classes.

The novelty of the initiative lies in the swift

implementation of this program on a large scale both

for the students and for faculty members. Another

study from India has previously reported using the

same platform, but restricted to a single specialty

[10]. We believe our early experience can serve as a

model for educational institutes looking for

continuing medical education in situations that

disrupt traditional teaching.

Contributors:

All authors have contributed, designed and approved

the study.

Funding:

None; Competing interest: None stated.

REFERENCES

1.

Pather N, Blyth P, Chapman JA, Dayal MR,

Flack NAMS, Fogg QA, et al. Forced disruption

of anatomy education in Australia and New Zealand:

An acute response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Anat Sci

Educ. 2020 Apr 18. Available from

https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.

wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/ase.1968. Accessed

April 23, 2020.

2.

Rose S. Medical student education in the time

of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Mar 31. Available from:

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2764138.

Accessed April 14, 2020.

3.

Liang ZC, Ooi SBS, Wang W. Pandemics and

their impact on medical training: Lessons from

Singapore. Acad Med. 2020 Apr 17. Available from

https://journals.lww.com/

academicmedicine/Abstract/9000/Pandemics_and_

Their_Impact_on_Medical_Training_.97208.aspx.

Accessed April 23, 2020.

4.

Li L, Xv Q, Yan J. COVID-19: The need for

continuous medical education and training. Lancet

Respir Med. 2020;8:e23.

5.

Patil NG, Yan YCH. SARS and its effect on

medical education in Hong Kong. Med Educ.

2003;37:1127-8.

6.

Park SW, Jang HW, Choe YH, Lee KS, Ahn YC,

Chung MJ, et al. Avoiding student infection

during a Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)

outbreak: A single medical school experience. Korean

J Med Educ. 2016;28:209-17.

7.

Hodgson JC, Hagan P. Medical education

adaptations during a pandemic: transitioning to

virtual student support. Med Educ. 2020 April 14.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/

medu.14177. Accessed April 23, 2020.

8.

Moszkowicz D, Duboc H, Dubertret C, Roux D,

Bretagnol F. Daily medical education for confined

students during COVID-19 pandemic: A simple

videoconference solution. Clin Anat. 2020 Apr 6.

Available from:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ca.23601.

Accessed April 23, 2020.

9.

Singh K, Mahajan R, Singh T, Gupta P. Flipped

classroom: A concept for engaging medical students

in learning. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:507-12.

10.

Dash S. Google classroom as a learning

management system to teach biochemistry in a medical

school. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2019;47:404-7.