In the face of the severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, the Indian

government has proactively taken multiple measures to slow

down disease progression. This includes converting some

hospitals to dedicated COVID-19 hospitals, and shutting down

many routine hospital services including outpatient

departments and elective operation theatres, while emergency

services have continued. However, the patients face a tough

dilemma of risk of infection during hospital visits

vis-a-vis denial of adequate care because of these

measures [1].

To ensure continued health services, the government

has given guidelines for practicing telemedicine to aid

continuous delivery of healthcare services to the public.

Telemedicine is defined as the delivery of health care

services, where distance is a critical factor, by all

healthcare professionals using information or communication

technology. It serves the purpose of exchange of valid

information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease

and injury, research and evaluation, and lessens overcrowding

in hospitals, especially in the time of a pandemic [2,3].

Telemedicine aims to ensure equitable services to everyone, is

cost-effective, provides safety to both patient and doctors

during pandemics, and offers timely and faster care. Since

children represent a vulnerable population, detailed guidance

on the delivery of primary and emergent care via

telemedicine services is the need of the hour.

Telemedicine can be classified on the basis of mode

of communication as (i) audio, video or

text-based (video mode is preferred as it allows limited

examination as well); (ii) timing of information

transmitted as real time or asynchronous exchange;

(iii) purpose of consult as first

time or follow up (in non-emergent cases or emergency

consultation); and (iv) according to individuals

involved as patient to medical practitioner, caregiver

to medical practitioner, medical practitioner to medical

practitioner or health worker to medical practitioner [2]. The

use of telemedicine ranges from educational purposes such as

teleconferencing and tele-proctoring, health care delivery,

screening of diseases, and disaster management [3].

Telemedicine is widely used in areas of radiology, dermatology

and pathology; but has had a limited role in other branches in

the past. In 2018, the Bombay High Court had convicted a

doctor couple who were guilty of criminal negligence and death

of a lady after delivery because the doctor had not come and

physically examined the patient. The attending doctor directed

her staff telephonically for patient management. The Supreme

Court at that time had advised doctors to limit the use of

telemedicine and to use it only in emergencies [4]. This will

now change with the latest guidelines [2]. Despite all its

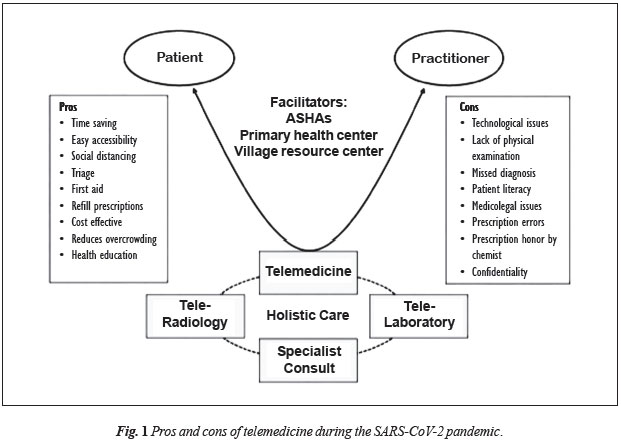

advantages, practicing telemedicine poses several challenges

to clinicians as it is an evolving tool (Fig. I).

|

Following are some of the issues that need to be

addressed by pediatricians in the current setting of the

COVID-19 pandemic in an Indian scenario and their possible

solutions.

Lack of Physical Examination

Telemedicine has an inherent drawback since the patient is not

actually present and a thorough physical examination is not

possible. The limited examination, which is possible only

through inspection, might be hampered by low video quality or

lack of video facilities altogether. The younger the child

(especially below 2 years), the more difficult it is to make a

diagnosis based on history alone because of overlapping and

nonspecific symptoms in children. This can often lead to

underestimation or misinterpretation of the disease. To

overcome this we can ask the patients to give a detailed

description about their complaints and not merely state the

issues. We can employ the use of peripheral examination

devices like electronic stethoscope, electronic blood pressure

apparatus, pulse oximeter and ultrasonography. However,

accuracy and effectiveness of these devices needs to be

ascertained before recommendations can be made. One way to

partially overcome this challenge is to encourage telemedicine

between a health worker and pediatrician to facilitate a

rudimentary examination [5]. The pediatrician may need to have

a low threshold for ordering basic investigations because of

the limited examination possible. The health care worker can

certainly assist in triaging patients and identifying sick

children requiring an urgent inpatient visit. If no hospital

is available nearby, telemedicine might be the only option

available e.g. in a case with trauma, pediatrician can

advise appropriate first aid which may be lifesaving after

which the patient can visit the nearest hospital for

assessment of the extent of trauma and stabilization.

Medico-legal Considerations

With the issue of telemedicine practice guidelines under the

Indian Medical Council Act, 1956, medical practitioners are

now empowered and legally protected to provide telemedicine

services according to guidelines stated [2]. Clinicians may

face difficulties in providing telemedicine services in

medicolegal cases as detailed documentation is required.

Doctors should avoid giving advice in such cases and the

patient must be referred for an urgent in-person visit to the

nearest hospital.

Informed Consent

In cases where patient initiates the conversation, the consent

is implied, but if a doctor initiates the conversation an

informed consent should be taken and documented. For a minor

seeking health care, child assent is also required. The

patient and the parent can send an email, text or an

audio/video message. Wherever in doubt, consent must be

documented/ recorded.

Prescription and Liability

The doctor is liable for any advice he gives. In case the

physician takes advice from another doctor, the liability lies

on the primary physician and it is his discretion whether or

not to follow the other doctors’ advice. He can give a list of

probable or differential diagnosis and can advise the patient

to visit the nearest hospital. Unless the physician is sure of

the diagnosis, no prescription should be given – rather,

patient should be advised to visit the nearest health

facility. Age and weight are important parameters in children

for dosage calculation. Hence we must avoid giving

prescriptions if these parameters are not known. For patients

with chronic diseases, assessment of disease activity becomes

difficult and certain medications e.g. narcotics,

psychotropic drugs etc. are prohibited

for telemedicine use by the authorities. The

prescriptions when given should be in the specified format [2]

and can be counter checked at any point.

Proper record-keeping is essential for first time

and refill prescriptions (allowed for a maximum 6-month period

without onsite visit). A screenshot record of whatsapp chats,

emails texts and video recording can be kept. The pediatrician

can also ask the caregiver to call back when he feels the

symptoms are in evolving phase. Documenting the call-back

instructions given to parents is often as important as

documenting the reported symptoms to cover liability risks.

Prescriptions for common symptoms can be easily copied by

quacks in large numbers leading to irrational drug use and

quackery. For this we should have stringent laws and any

defaulter should face vigorous punishment.

Confidentiality

The practitioner can choose his telemedicine consultation

timings as per convenience. It is his choice to accept or

decline a consultation at any time. It is duty of the doctor

to maintain patient confidentiality and not to share patient

details without consent. Patient images should be sent via

secure, encrypted means of communication [6]. However, in case

either party records conversation there can be a breakdown of

the doctor-patient relationship. This relationship has

multiple cultural influences. The patient’s trust in his/her

doctor is not acquired in a moment, but in long coexistence,

especially in situations of risk [9]. The government

guidelines are not very explicit on how to address any

barriers or chinks in doctor-patient relationship. However,

the practitioner is not liable if the patient information gets

shared due to technological issues [2].

Fee

A similar fee structure as applied for inpatient visits is

applicable here as well. Telemedicine is much more economical

both for the patient and physician as it reduces cost of

travel and stay (during out-station consultations). The Indian

Academy of Pediatrics has recently introduced an app for its

members, which can be used for telemedicine consultation and

payment services.

Holistic Care

Using telemedicine, it is possible to provide a more holistic

care faster e.g., we can take advice from the expert in

a shorter duration without referring the patient for expert

opinion. Services such as tele-radiology, tele-pathology will

also aid us in faster diagnosis. Common procedures (such as

use of metered dose inhalers, technique of giving insulin

injections) can be shared with the patient/caregiver via

YouTube links, pre-prepared videos or live demonstrations.

Needless to say, this would be possible on a case-case basis

depending on the literacy and understanding of the

patient/caretaker. We can also screen patients through

telecommunication. In case we find a disease suspect we can

refer the patient for urgent testing, isolation and

management. However, certain issues like child abuse and/or

sexual abuse remain outside the purview of telemedicine in

India currently and a hospital visit would be required.

Technological Issues

Lack of widespread access to telecommunication facilities to

the wider public leads to inequitable access to health

services via telemedicine. For example, if there is a

transient error in voice transmission the patient might

receive incomplete information which can be hazardous and may

have medico-legal implications. Any breakdown in technology

should preferably be documented by the provider.

Communication

The primary person of contact in the pediatric age group is

usually not the patients themselves, but the parents or the

caregivers. The already difficult doctor-patient communication

is further compounded with telecom-munication. Moreover,

patient literacy and socio-economic factors might pose

challenges in communi-cation during telephone or video

calling. Prescriptions via this mode can also be

incorrectly interpreted, either by the patients themselves or

the chemists, which can lead to disastrous results. The

solution is to have good quality internet connections,

uninterrupted power supply, workshops on telecommunication,

and designated centers such as post offices, dispensaries and

primary health care centers where good internet services and

trained facilitators like Accredited Social Health Activists

(ASHAs) are available (Fig. I). The staff should

be trained in performing video calls and explaining

prescription to the patients. We should avoid providing

telemedicine by telephonic conversations and should encourage

video calls and provide prescriptions in the fixed format

via email. We should have a better liaison between

tertiary care hospitals and primary heath care centers, as has

been done with the Village resource centers developed by

Indian Space Research Organisation in October, 2018 [8]. If

the practitioner still faces communication glitches, he can

record the issue and terminate the conversation [2].

We as physicians have become comfortable with the

traditional method of providing treatment but in the current

scenario of the COVID-19 pandemic, a temporary change is

required [9]. With more and more healthcare professionals

getting affected, the doctor-patient ratio will further

deteriorate. Telemedicine might be the only promising solution

available. However as the usage of telemedicine will increase

in India, more issues regarding medicolegal aspects might

emerge, which should be deliberated among the medical

fraternity a priori. Although caution is necessary on

the part of a pediatrician, given the benefits of telemedicine

we must welcome it. We may find it as an important adjunct to

the traditional way of practicing medicine.

Contributors:

VM: conceived the idea, is providing telemedicine services,

wrote the 1st draft, and approved the final manuscript; TS:

literature search, assisted in writing the first draft and

approved the final manuscript; CA: edited the manuscript, and

approved the final manuscript.

Funding:

None; Competing interest: None stated.

REFERENCES

1.

Keesara, S, Jonas A, Schulman K. Covid-19 and health

care’s digital revolution. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e82.

Accessed April 10, 2020.

2.

Board of Governors. Telemedicine Practice Guidelines

Enabling Registered Medical Practitioners to Provide

Healthcare Using Telemedicine. Available from:

https://www.Mohfw.gov.in/pdf/telemedicine. Accessed April

5, 2020.

3.

Burke B, Hall R. Telemedicine: Pediatric applications.

Pediatrics. 2015;136:e293-e308

4.

Aggarwal KK. Prescription sans diagnosis: A case of

culpable neglect. India Legal. Available from:

https://www.indialegallive.com-ConstitutionalNews–Courts.

Accessed April 8, 2020.

5.

Lakhe A, Sodhi I, Warrier J, Sinha V. Development of

digital stethoscope for telemedicine. J Med Eng Technol.

2016;40:20-24.

6.

Arumugham S, Rajagopalan S, Rayappan JBB, Amirtharajan

R. Networked medical data sharing on secure medium - A web

publishing mode for DICOM viewer with three layer

authentication. J Biomed Inform. 2018;86:90-105.

7.

Luz PLD. Telemedicine and the doctor/patient

relationship. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;113:100-2.

8.

Village Resource Centre - ISRO [Internet]. 2020.

Available from:

https://www.isro.gov.in/applications/village-resource-centre.

Accessed April 18, 2020.

9.

Kittleson MM. The

invisible hand - medical care during the pandemic. N Engl J

Med. 2020; 382:1586-87.