|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2019;56: 566-570 |

|

Clinical Spectrum of Congenital Anomalies of

Kidney and Urinary Tract in Children

|

|

Bondada Hemanth Kumar 1,

Sriram Krishnamurthy1,

Venkatesh Chandrasekaran1,

Bibekanand Jindal2

and Ramesh Ananthakrishnan3

From Departments of 1Pediatrics, 2Pediatric

Surgery and 3Radiology, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate

Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India

Correspondence to: Dr Sriram Krishnamurthy,

Additional Professor, Department of Pediatrics, JIPMER,

Puducherry-605006, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: October 02, 2018;

Initial review: January 04, 2019;

Accepted: May 14, 2019.

|

|

Objective: To evaluate the

clinical spectrum and patterns of clinical presentation in congenital

anomalies of kidney and urinary tract. Methods: We enrolled 307

consecutively presenting children with congenital anomalies of kidney

and urinary tract at the pediatric nephrology clinic. Patients were

evaluated clinically, with serum biochemistry, appropriate imaging and

radionuclide scans. Results: The most common anomaly was primary

vesicoureteric reflux (VUR) (87, 27.3%), followed by pelviureteral

junction obstruction (PUJO) (62,20.1%), multicystic dysplastic kidney

(51 16.6%), non-obstructive hydronephrosis (32, 10.4%) and posterior

urethral valves (PUV) (23, 7.4%). 247 (80.4%) anomalies had been

identified during the antenatal period. Another 33 (10.7%) were

diagnosed during evaluation of urinary tract infection, and 21 (6.8%)

during evaluation for hypertension at presentation. Obstructive

anomalies presented earlier than non-obstructive (7 (3, 22.5) vs

10 (4, 24) mo: (P=0.01)). The median (IQR) ages of presentation

for children with PUV (n=23), VUR (n=87) and PUJO (n=62)

were 4 (2, 14) mo, 10 (5, 27) mo, and 7 (3, 22.5) mo, respectively. Nine

(2.9%) children had extrarenal manifestations. Conclusions: The

median age at clinical presentation for various subgroups of anomalies

indicates delayed referral. We emphasize the need for prompt referral in

order to initiate appropriate therapeutic strategies in children with

congenital anomalies of kidney and urinary tract.

Keywords: CAKUT, Hydronephrosis, Multicystic

renal dysplasia, Vesico-ureteral reflux.

|

|

C

ongenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary

tract (CAKUT) are an important cause of morbidity in children, and

contribute significantly to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). About 30-60%

of ESRD in children are due to CAKUT [1-4]. CAKUT includes a wide

spectrum of anomalies such as pelviureteral junction obstruction (PUJO),

multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK), renal hypodysplasia, horse-shoe

kidney, ectopic kidney, primary vesicoureteric reflux (VUR), posterior

urethral valve (PUV), and vesicoureteral junctional obstruction (VUJO).

It is important to diagnose these anomalies and initiate therapy to

prevent or delay the onset of ESRD. We therefore, studied the clinical

presentation patterns in children with CAKUT. The primary objective of

this study was to evaluate the clinical spectrum and patterns of

clinical presentation in CAKUT. The secondary objectives were to study

the clinical characteristics of obstructive and non-obstructive CAKUT,

and to study the extrarenal manifestations in these patients.

Methods

This descriptive study was conducted at the Pediatric

Nephrology outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital from December 2015

through September 2017 after obtaining approval from the Institute

Ethics Committee.

The study recruited consecutively presenting children

aged <13 years with CAKUT. Children with polycystic kidneys and

neurogenic bladder were excluded. Definitions of clinical entities –

acute kidney injury (AKI) [5], urinary tract infection (UTI) [6],

chronic kidney disease (CKD) [7] and hypertension [8] – were as per

standard guidelines.The diagnosis and management of antenatal

hydronephrosis was performed as per standard guidelines [9,10]. Weight

for age Z scores were calculated from WHO growth charts [11]. The

diagnostic criteria for various CAKUT were as follows:

(a) PUJO: PUJO was defined by an

obstructive pattern on ethylenecysteamine (EC) diuretic renography

i.e., a curve that rises continuously over 20 minutes or

plateaus, despite furosemide administration and post-micturition

[10].

(b) PUV: The diagnosis was

established by a micturating cystourethrography (MCU) showing

dilated or elongated prominent posterior urethra; and confirmed by

cystoscopy.

(c) Primary VUR: MCU was performed

for confirming the diagnosis of primary VUR, and then classified

into grades I to V [12]. Secondary VUR was excluded by presence of

bladder anomalies/ureterocele.

(d) MCDK: It was diagnosed by

unilateral multiple cysts of varying sizes on ultrasound, with

altered echoes without cortico-medullary differentiation; and a DMSA

renal scan showing minimal/ no function.

(e) Other anomalies such as renal

hypoplasia/dysplasia, horseshoe kidney, crossed renal ectopia,

duplex-collecting system were diagnosed on renal ultrasonogram.

Clinical and laboratory data were recorded in a cross

sectional manner in a pre-designed structured proforma.

Statistical analyses: Normally distributed data

was compared by Student’s t-test, non-normally distributed data by

Mann-Whitney U test, and proportions by chi-square test/ Fisher’s exact

test. SPSS 23.0 software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois) was used for

analysis.

Results

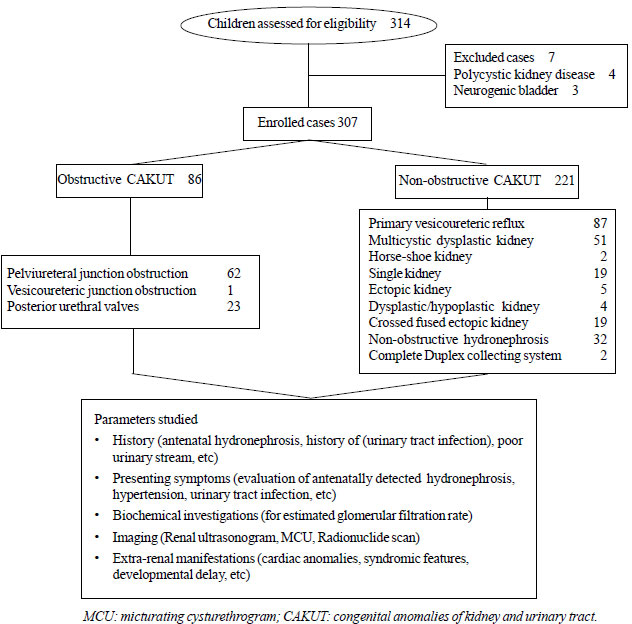

A total of 307 children with CAKUT were enrolled (Fig.

1). Primary VUR was the commonest anomaly followed by PUJO

and MCDK. The median ages of presentation of various anomalies are

summarized in Table I.

|

|

Fig. 1 Flow chart depicting

methodology of the study.

|

TABLE I Profile of Children with Congenital Anomalies of Kidney and Urinary Tract (N=307)

|

Diagnosis |

No. (%) |

Gender |

Age at diag- |

|

|

(male: |

nosis (mo) |

|

|

female) |

median (IQR) |

|

Primary VUR |

87 (28.3) |

54:33 |

10 (5, 27) |

|

Grade 1 |

4 |

|

|

|

Grade 2 |

35 |

|

|

|

Grade 3 |

31 |

|

|

|

Grade 4 |

14 |

|

|

|

Grade 5 |

3 |

|

|

|

PUJO

|

62 (20.1) |

42:20 |

7 (3, 22.5) |

|

Unilateral |

58 |

|

|

|

Bilateral |

4 |

|

|

|

MCDK |

51 (16.6) |

29:22 |

9 (2, 20) |

|

Right sided |

34 |

|

|

|

Left sided |

17 |

|

|

|

Non obstructive |

32 (10.4) |

22:10 |

8 (4, 12)

|

|

hydronephrosis* |

|

|

|

|

PUV |

23 (7.4) |

23:0 |

4 (2,14) |

|

Single kidney |

19 (6.1) |

13:6 |

13 (6, 36) |

|

Crossed fused

|

19 (6.1) |

11:8 |

10 (4, 36) |

|

ectopic kidney |

|

|

|

|

Left to right |

12 |

|

|

|

Right to left |

7 |

|

|

|

Ectopic kidney |

5 (1.6) |

2:3 |

12 (6,24) |

|

Dysplastic/Hypo- |

4 (1.3) |

4:0 |

30 (3.75, 70) |

|

plastic kidney |

|

|

|

|

Duplex collecting

|

2 (0.6) |

0:2 |

8 and 12# |

|

system |

|

|

|

|

Horse-shoe kidney |

2 (0.6) |

0:2 |

48 and 158# |

|

VUJO |

1 (0.3) |

1:0 |

25# |

|

PUV: Posterior urethral valve, PUJO: Pelviureteral junction

obstruction, MCDK: Multicystic dysplastic kidney, VUR:

Vesicoureteric reflux, VUJO: vesicoureteric junction

obstruction; *MCU and EC diuretic Renogram normal; #actual

ages. |

Out of the 307 children, 247 (80.4%) were detected

antenatally. Of this subgroup, 214 children had antenatal hydronephrosis.

The others included MCDK (n=26), single kidney (n=3),

crossed fused ectopic kidney (n=3) and ectopic kidney (n=1).

In 33 (10.7%) children, CAKUT was identified during work up for UTI,

while in 21 (6.8%), hypertension at presentation led to identification

of CAKUT. Eighteen children were incidentally detected to have CAKUT,

five were found to have CAKUT during evaluation for low eGFR, one child

during evaluation for poor urinary stream at 10 years of age, and one

child during evaluation for AKI. In two children, CAKUT was detected

during evaluation of nephrotic syndrome (one had primary VUR and another

had PUJO).

Among primary VUR (n=87), grade 3 was the

commonest. Primary VUR was bilateral in 29 (33.7%) children. Three

children (3.4%) were diagnosed during CKD work-up; 28 (32.1%) were

detected during workup for UTI. The mode of presentation of PUJO (n=62)

included antenatal detection in 90.4%; incidental detection in 6.5%,

following work up of UTI (1.6%) and during evaluation for nephrotic

syndrome (1.6%). Bilateral involvement was seen in 6%.Two children had

primary VUR in the contralateral kidney. Among MCDK cases (n=51),

8 children were incorrectly reported antenatally as hydronephrosis.

Three of these cases had primary VUR (2 in contralateral, 1 ipsilateral).

Among PUV cases (n=23), 86.9% had antenatal hydronephrosis; 78.2%

presented with low eGFR.

The median (IQR) ages of presentation for children

with PUV (n=23), VUR (n=87) and PUJO (n=62) were 4

(2,14) months, 10 (5,27) months and 7 (3, 22.5) months respectively.

Among these three CAKUT categories, 20 (86.9%), 54 (62.1%) and 56

(90.3%) had evidence of hydronephrosis in the antenatal ultrasounds.

Among the 307 enrolled children with CAKUT, weight

for age Z-score <-3 was noted in 29 (9.4%) children, while weight for

age Z-score between -2 to -3 was noted in 28 (9.1%) children.

Obstructive CAKUT presented earlier than

non-obstructive CAKUT (P=0.01) (Table II). A

greater proportion of obstructive CAKUTs were identified antenatally as

compared to non-obstructive CAKUTs (P=0.01). There was a male

preponderance in both groups. The proportions of children with UTI in

the obstructive versus non-obstructive CAKUT groups were 5.8% versus

12.6% respectively (P<0.01). The median eGFR for obstructive and

non-obstructive CAKUTs were 60 (48.3, 64.3) and 62.8 (60, 73.3) mL/min/1.73

m 2 (P<0.01).

TABLE II Comparison Between Obstructive and Non-obstructive Anomalies

|

Obstructive* |

Non-Obstructive |

P |

|

(n=86) |

**(n=221) |

value |

|

Antenatal diagnosis

|

77(89.5) |

170 (76.9) |

0.01 |

|

Male sex

|

56 (65.2) |

140 (63.3) |

0.02 |

|

UTI

|

5 (5.8) |

28 (12.6) |

<0.01 |

|

#$eGFR

|

60 (48.3,64.3) |

62.8 (60,73.3) |

<0.01 |

|

Hypertension at

|

7 (8.1) |

14 (6.3) |

0.12 |

|

presentation

|

|

|

|

|

#Age at diagnosis (mo)

|

7 (3,22.5) |

10 (4,24) |

0.01 |

|

*Comprised of Posterior urethral valve, Pelviureteral

junction obstruction, and Vesico-ureteric junction

obstruction;**comprised of primary vesicoureteric reflux,

Multicystic dysplastic kidney, Renal agenesis, Renal

hypo-dysplasia, pelvic kidney, horse shoe kidney, crossed fused

ectopia, Complete duplex collecting system; $in mL/min/173m2;

All values in n(%) except #median (IQR). |

Overall, 9 children (2.9%) had extrarenal

manifestations. One primary VUR case had Down syndrome, another had

VACTERL association. Three children with MCDK had cardiac anomalies

[ventricular septal defect (VSD): 2, atrial septal defect: 1], while 2

primary VUR cases had cardiac anomalies (VSD: 1, TOF:1). One child with

PUJO had VSD; and 1 child had developmental delay.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study assessed the clinical

profile in a cohort of 307 CAKUT cases. Obstructive CAKUTs presented

earlier causing significant impairment of e-GFR as compared to the

non-obstructive CAKUTs. This finding is comparable to earlier studies

[13,14]. Primary VUR was the commonest CAKUT followed by PUJO, MCDK,

non-obstructive hydronephrosis and PUV. In contrast, Soliman, et al.

[13], reported PUV (36.4%) as the commonest followed by primary VUR

(19.6%) and PUJO (18.7%). Aksu, et al. [15], reported PUJO in

62.7% followed by VUR in 16.6%. It is notable that we encountered quite

delayed presentations of various CAKUTs, particularly PUV and PUJO. This

can be inferred from the fact that though a majority of these CAKUTs had

evidence of antenatal hydronephrosis, their median age at presentation

to us was at a much later point of time. A significant number of

children had low eGFR or hypertension at presentation, which is

comparable to a previously published report [15]. Though a significant

number of children were detected antenatally, approximately 19.5% of the

CAKUTs had not been antenatally identified, and a majority of this

sub-group were identified after UTI.

We encountered significant number of MCDK cases

(16.6%) in contrast to previously reported studies [13], possibly due to

a referral bias. We also found only 2.9% prevalence of extrarenal

features in children with CAKUT. These extrarenal anomalies were

detected in primary VUR, PUJO and MCDK cases, but not in children with

PUV. This finding is different from a previous Egyptian report, wherein

57% of 107 CAKUT children had extrarenal features. The reasons for this

could be related to different ethnicity. The parental consanguinity in

our study cohort was 21% whereas it was 50.5% in this report [13].

There is paucity of published studies on the profile

of CAKUT from India; and this study provides valuable information

regarding this subject. Our study has few limitations. The study was

conducted at referral hospital and the profile of enrolled subjects may

not be representative of the disease profile at the community level.

Also, we could not perform genetic testing of patients enrolled in this

study.

It is known that a percentage of milder forms of

CAKUT can be diagnosed later in life. Nevertheless, the median ages of

presentation (despite a majority of them having had evidence of

antenatal hydronephrosis) suggests a delayed referral. This study

emphasizes the need for prompt referral by trained professionals in

order to initiate appropriate therapeutic strategies in children with

CAKUT and improvise the care bundle provided to these children.

Contributors: BHK: collected the data and

drafted the first version of the manuscript; SK: conceptualized the

study, was responsible for medical management of the cases, interpreted

the data and critically revised the manuscript. RA: confirmed the

radiological findings and critically reviewed the manuscript. VC:

responsible for surgical management of cases and critically reviewed the

manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript,

and are accountable for all aspects of the study. SK: shall act as

guarantor of the paper.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

•

The most common congenital anamalies of the kidney and

urinary tract (CAKUT) in our series were vesicoureteric reflux,

pelviureteric junction obstruction, multicystic dysplastic

kidney, non-obstructive hydronephrosis and posterior urethral

valves.

•

About one-fifth of anomalies had not been detected

antenatally.

•

Obstructive CAKUT presented earlier than non-obstructive

CAKUT.

|

References

1. Harambat J, van Stralen KJ, Kim JJ, Tizard EJ.

Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol.

2012;27:363-73.

2. North American Pediatric Renal Transplant

Cooperative Study (NAPRTCS) (2008) 2008. Annual report. The EMMES

Corporation, Rockville, MD. Available from:

https://web.emmes.com/study/ped/annlrept/Annual%20 Report%20-2008.pdf.

Accessed May 14, 2019

3. Mong Hiep TT, Ismaili K, Collart F,

Damme-Lombaerts R, Godefroid N, Ghuysen MS, et al. Clinical

characteristics and outcomes of children with stage 3–5 chronic kidney

disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:935-40.

4. Hattori S, Yosioka K, Honda M, Ito H, Japanese

Society for Pediatric nephrology. The 1998 report of the Japanese

National Registry data on pediatric end-stage renal disease patients. Pediatr

Nephrol. 2002;17:456-61.

5. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute

Kidney Injury 2012. Available from: https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/KDIGO-2012-AKI-Guideline-English.

pdf. Accessed May 14, 2019

6. Indian Society of Pediatric Nephrology,

Vijayakumar M, Kanitkar M, Nammalwar BR, Bagga A. Revised statement on

management of urinary tract infections. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:709-17.

7. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical

Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation,

Classification, and Stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1-266.

8. National High Blood Pressure Education Program

Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The

Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood

Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555-76.

9. Nguyen HT, Herndon CDA, Cooper C, Gatti J, Kirsch

A, Kokorowski P, et al. The Society for Fetal Urology Consensus

Statement on the Evaluation and Management of Antenatal Hydronephrosis.

J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6: 212-31.

10. Sinha A, Bagga A, Krishna A, Bajpai M, Srinivas

M, Uppal R, et al. Revised guidelines on management of antenatal

hydronephrosis. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:215-31.

11. WHO child growth standards: Weight-for-age, World

Health Organization; 2006. Available from: https://

www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/weight_for_age/en/. Accessed May

14, 2019.

12. Lebowitz RL, Olbing H, Parkkulainen KV, Smellie

JM, Tamminen-Möbius TE. International System of Radiographic Grading of

Vesicoureteric Reflux. International Reflux Study in Children. Pediatr

Radiol. 1985;15:105-9.

13. Soliman NA, Ali RI, Ghobrial EE, Habib EI, Ziada

AM. Pattern of clinical presentation of congenital anomalies of the

kidney and urinary tract among infants and children. Nephrol (Carlton).

2015;20:413-8.

14. Ahmadzadeh A, Tahmasebi M, Gharibvand MM. Causes

and outcome of prenatally diagnosed hydronephrosis. Saudi J Kidney Dis

Transplant 2009;20:246-50.

15. Aksu N, Yavaþcan O, Kangin M, Kara OD, Aydin Y,

Erdoðan H, et al. Postnatal management of infants with

antenatally detected hydronephrosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005:20:1253.

|

|

|

|

|