|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2018;55:573-575 |

|

Hepatic and Cardiac

Iron-load in Children on Long-term Chelation with Deferiprone

for Thalassemia Major

|

|

Sidharth Totadri 1,

Deepak Bansal1,

Amita Trehan1,

Alka Khadwal2,

Anmol Bhatia3,

Kushaljit Singh Sodhi3,

Prateek Bhatia1,

Richa Jain1,

Reena Das4 and

Niranjan Khandelwal3

From 1Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Unit,

Department of Pediatrics, Advanced Pediatrics Center, 2Clinical

Hematology unit, Department of Internal Medicine and Departments of

3Radiodiagnosis and Imaging, and 4Laboratory

Hematology; Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research,

Chandigarh, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Deepak Bansal, Professor,

Hematology-Oncology unit, Department of Pediatrics, Advanced Pediatrics

Center, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research,

Chandigarh, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: November 13, 2017;

Initial review: March 16, 2018;

Accepted: April 28, 2018.

|

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of prolonged deferiprone

monotherapy in patients with

b-thalassemia

major. Methods: This cross-sectional study included 40 patients

(age range 9 to 38 years) with thalassemia major receiving deferiprone

for ³5

years. Serum ferritin, and myocardial iron concentration (MIC) and liver

iron concentration (LIC) assessed by T2*MRI were recorded. Results:

The patients were receiving deferiprone for a mean (SD) duration of 12.1

(4.7) years. The median (IQR) dose of deferiprone was 85 (74.3, 95)

mg/kg/day. The MIC was normal or had a mild, moderate or severe

elevation in 29 (72.5%), 3 (7.5%), 3 (7.5%), and 5 (12.5%) patients. The

LIC was normal or had a mild, moderate or severe elevation in 2 (5%), 4

(10%), 11 (27.5%) and 23 (57.5%) patients. Conclusions: The

majority of patients receiving deferiprone had a moderate/severe hepatic

but normal cardiac iron load. Prolonged deferiprone monotherapy was

suboptimal for hepatic iron load in the majority.

Keywords: Cardiac failure, Hemosiderosis, Hepatic fibrosis,

Oral iron chelators.

|

|

I

n low- and middle-income countries (LMIC),

deferiprone is a popular and cost-effective option for iron chelation in

patients with b-thalassemia

major [1]. Desferrioxamine is seldom preferred due to its arduous route

of administration and cost [2]. Serum ferritin is commonly performed to

ascertain the iron overload in thalassemic patients. However, it is an

acute phase reactant, and a trend is more indicative than a single value

[3,4]. T2* magnetic resonance imaging (T2*MRI) has emerged as a

non-invasive tool, providing a more accurate estimate of cardiac and

hepatic hemosiderosis. We report the status of iron overload in patients

with thalassemia major who were receiving deferiprone monotherapy for a

prolonged duration.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the

thalassemia day care center in Department of Pediatrics at PGIMER,

Chandigarh, India. Inclusion criteria were: (i) A diagnosis of

thalassemia major confirmed by hemoglobin electrophoresis or

high-performance liquid chromatography, (ii) receiving

deferiprone monotherapy for a duration of

³5 years, and (iii)

a T2*MRI performed in the previous 12 months. The exclusion criteria

included: (i) exposure to either desferrioxamine or deferasirox,

(ii) poor compliance (defined as >3 episodes of missing >25% of

the recommended dose/month) or a daily deferiprone dose <65 mg/kg. The

patients were enrolled between January 2017 and March 2017. The mean

serum ferritin over the previous 12 months was calculated. Serological

evidence for Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis B (HBsAg) and

Hepatitic C (Anti-HCV-IgG) obtained in the preceding 12 months was also

recorded.

T2*MRI utilized a body coil on a 1.5-T magnetic

resonance scanner (MAGNETOM Aera, Siemens Healthcare). An elevation in

liver iron concentration (LIC) was categorized as: normal (<2 mg/g),

mild (2-7 mg/g), moderate (7-15 mg/g) or severe (>15 mg/g) [5]. An

elevation in myocardial iron concentration (MIC) was categorized as:

normal (<1.16 mg/g), mild (1.16-1.65 mg/g), moderate (1.65-2.71) or

severe (>2.71 mg/g) [5].

The study was approved by our Institute’s Ethics

Committee. An informed written consent was obtained from patients and/or

their caregivers.

Statistical analysis: The data was analyzed with

SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparison of

proportions was performed with either Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test.

The Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient was utilized for

assessment of correlation between MIC, LIC and serum ferritin.

Results

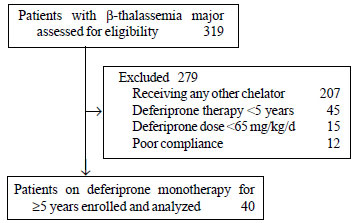

Forty patients were enrolled (Fig. 1).

The mean (SD) age was 23.4 (7.1) years (range 9-38 years). The mean (SD)

duration of receiving chelation with deferiprone was 12.1 (4.7) years

(range 5-22 years). Twenty-nine (72.5%) patients were receiving

deferiprone for ³10

years. The median (IQR) dose of deferiprone at enrolment was 85 (74.3,

95.0) mg/kg/day. The median (IQR) frequency of blood transfusions

administered to the patients was at 3 (3, 3) weekly interval. Thirteen

(32.5%) patients had undergone a splenectomy. Serology was reactive for

HBSAg, anti-HCV-IgG and HIV in 2 (5.3%), 4 (10.5%) and none of the 38

patients, respectively (reports were unavailable in two patients).

|

|

Fig. 1. Flow of patients in

the study.

|

The median (IQR) serum ferritin was 2271.5 (1369.0,

3089.3) ng/mL. The distribution of iron overload based on MIC and LIC is

illustrated in Table I. Amongst 32 patients with a

normal/mildly elevated MIC, 27 (84%) had a moderate/severe elevation in

LIC.

TABLE I Distribution of Cardiac and Liver Iron Overload in Pateients Receiving Deferiprone >5 years (N=40)

|

Iron

|

Myocardial iron

|

Liver iron

|

|

overload |

concentration (MIC) |

concentration(LIC) |

|

Normal |

29 (72.5) |

2 (5) |

|

Mild |

3 (7.5) |

4 (10) |

|

Moderate |

3 (7.5) |

11 (27.5) |

|

Severe |

5 (12.5) |

23 (57.5) |

|

Values in no(%). |

|

|

The serum ferritin correlated with LIC (r=0.499, P=0.001),

but not with MIC (r=0.280, P=0.080). Neither MIC nor LIC

correlated with the duration of deferiprone therapy.

Splenectomy did not influence cardiac (P=0.52)

or liver iron overload (P=0.29). Viral infections did not affect

cardiac (P=0.34) or liver iron overload (P=0.65). Presence

of moderate/severe cardiac or liver iron overload did not differ among

patients receiving £90

or >90 mg/kg/day of deferiprone (P=0.06 and 0.14, respectively).

Discussion

In this study, we report a group of patients

receiving deferiprone monotherapy – the mean duration of therapy

exceeding a decade. In our study, while serum ferritin demonstrated

correlation with LIC, there was a lack of correlation with MIC.

Three-fourths of the patients had a normal or a merely mildly increased

MIC. A moderate or severe iron overload was observed in 85% of the

patients.

The limitations of this study include a

cross-sectional design, and a lack of information on the dose of

deferiprone administered in the preceding years. A proportion of

patients were receiving deferiprone at a dose of 65-75 mg/kg/day.

Historical assessment of compliance can also be unreliable. Adverse

events of deferiprone were not described due to the cross-sectional

design of the study. There was a lack of comparison with patients

receiving desferrioxamine or deferasirox.

The cardiac chelating effect of deferiprone is

reiterated by our study. Studies evaluating its efficacy have

demonstrated improvement in myocardial hemosiderosis, comparable to or

superior to desferrioxamine [6,7]. International guidelines concur on

the importance of maintaining a low LIC in addition to MIC [3,8].

Several studies have demonstrated that deferiprone monotherapy lags

behind desferrioxamine and deferasirox in reducing LIC [9-12]. A

possible ‘bottleneck effect’, wherein, deferiprone is able to chelate

merely the iron available in the chelatable pool is postulated [13]. An

inferior iron chelation from the liver might in part be related to

inadequate doses of deferiprone [14]. However, in our study, even

patients receiving >90 mg/kg/day of deferiprone did not have a lower

liver iron overload.

We conclude that patients of thalassemia major

receiving long-term monotherapy with deferiprone have a high prevalence

of moderate or severe hepatic iron overload and a relatively low

prevalence of moderate or severe cardiac iron overload. Alternative

chelation strategies may be considered in patients with a high LIC on

monotherapy with deferiprone.

Contributors: ST: collected data, analyzed data

and drafted the manuscript; DB: conceptualized and designed the study,

collected data and edited the manuscript; AT, RJ: were pediatric

haematologists who contributed to clinical care and collection of

clinical data, supervised and edited the manuscript; AK: was the adult

haematologist who contributed to clinical care of older patients and

collection of clinical data, supervised and edited the manuscript; AB,

KSS: performed and reported T2*MRI scans, were responsible for

methodology of T2*MRI, supervised and edited the manuscript; NK:

standardized the software of the T2*MRI and reviewed all T2*MRI reports,

supervised and edited the manuscript; PB, RD: reported serum ferritin,

haemoglobin electrophoresis and high-performance liquid chromatography,

supervised and edited the manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

|

What This Study Adds?

• Long term chelation with deferiprone

monotherapy in patients with

b-thalassemia

major was found to be suboptimal for liver iron overload in

majority of the patients.

|

References

1. Verma IC, Saxena R, Kohli S. Past, present and

future scenario of thalassaemic care & control in India. Indian J Med

Res. 2011;134:507-21.

2. Kwiatkowski JL. Real-world use of iron chelators.

Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011: 451-8.

3. Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Porter J, Taher A,

Viprakasit V. Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion Dependent

Thalassemia. 3rd ed. Nicosia, Cyprus: Thalassaemia International

Federation; 2014.

4. Kolnagou A, Yazman D, Economides C, Eracleous E,

Kontoghiorghes GJ. Uses and limitations of serum ferritin, magnetic

resonance imaging T2 and T2* in the diagnosis of iron overload and in

the ferrikinetics of normalization of the iron stores in thalassemia

using the International Committee on Chelation deferiprone/deferoxamine

combination protocol. Hemoglobin. 2009;33:312-22.

5. Mandal S, Sodhi KS, Bansal D, Sinha A, Bhatia A,

Trehan A, et al. MRI for quantification of liver and cardiac iron

in thalassemia major patients: Pilot study in Indian population. Indian

J Pediatr. 2017;84:276-82.

6. Pennell DJ, Berdoukas V, Karagiorga M, Ladis V,

Piga A, Aessopos A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of

deferiprone or deferoxamine in beta-thalassemia major patients with

asymptomatic myocardial siderosis. Blood. 2006;107:3738-44.

7. Kuo KH, Mrkobrada M. A systematic review and

meta-analysis of deferiprone monotherapy and in combination with

deferoxamine for reduction of iron overload in chronically transfused

patients with b-thalassemia.

Hemoglobin. 2014;38:409-21.

8. Saliba AN, Harb AR, Taher AT. Iron chelation

therapy in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients: current

strategies and future directions. J Blood Med. 2015;6:197-209.

9. Pepe A, Meloni A, Rossi G, Cuccia L, D’Ascola GD,

Santodirocco M, et al. Cardiac and hepatic iron and ejection

fraction in thalassemia major: Multicentre prospective comparison of

combined deferiprone and deferoxamine therapy against deferiprone or

deferoxamine monotherapy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:1.

10. Perifanis V, Christoforidis A, Vlachaki E, Tsatra

I, Spanos G, Athanassiou-Metaxa M. Comparison of effects of different

long-term iron-chelation regimens on myocardial and hepatic iron

concentrations assessed with T2* magnetic resonance imaging in patients

with beta-thalassemia major. Int J Hematol. 2007;86:385-9.

11. Berdoukas V, Chouliaras G, Moraitis P, Zannikos

K, Berdoussi E, Ladis V. The efficacy of iron chelator regimes in

reducing cardiac and hepatic iron in patients with thalassaemia major: a

clinical observational study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;28;11:20.

12. Pepe A, Meloni A, Capra M, Cianciulli P,

Prossomariti L, Malaventura C, et al. Deferasirox, deferiprone

and desferrioxamine treatment in thalassemia major patients: cardiac

iron and function comparison determined by quantitative magnetic

resonance imaging. Haematologica. 2011;96:41-7.

13. Fischer R, Longo F, Nielsen P, Engelhardt R,

Hider RC, Piga A. Monitoring long-term efficacy of iron chelation

therapy by deferiprone and desferrioxamine in patients with beta-thalassaemia

major: application of SQUID biomagnetic liver susceptometry. Br J

Haematol. 2003;121:938-48.

14. Kwiatkowski JL, Belmont A. Deferiprone for the

treatment of transfusional iron overload in thalassemia. Expert Rev

Hematol. 2017;10:493-503.

|

|

|

|

|