|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: 589-593 |

|

Rotavirus Infections in

Children Vaccinated Against Rotavirus in Pune, Western India

|

|

Preeti Jain, Gopalkrishna Varanasi, Rohan Ghuge,

*Vijay Kalrao, #Ram

Dhongade, $Ashish

Bavdekar, ‡Sanjay

Mehendale and Shobha Chitambar

From Enteric Viruses Group, National Institute of

Virology, Pune; *Bharati Vidyapeeth Medical College and Hospital, Pune;

#Sant Dnyaneshwar Medical Foundation & Research Centre’s

Shaishav Clinic, Pune; $King Edward Memorial Hospital, Pune;

and ‡National Institute of Epidemiology, Chennai; India.

Correspondence to: Dr Shobha D Chitambar, Enteric

Viruses Group, National Institute of Virology, 20-A, Ambedkar Road, PO

Box No 11, Pune 411 001, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

Objective: To characterize rotavirus infections detected in

rotavirus vaccinated children hospitalized for acute gastroenteritis.

Design: Observational, hospital-based study.

Setting: Three hospitals in Pune, Western India.

Participants: Children aged <5 years hospitalized

for acute gastroenteritis during 2013-14.

Methods: Rotavirus capture ELISA was performed on

all stool samples that were collected from patients following informed

consent from parents. VP7 and VP4 genes of rotavirus strains were

genotyped by multiplex RT-PCR. Stool samples from vaccinated children

were tested for other enteric viruses.

Results: Among the 529 children, 53 were

vaccinated with at least one dose of the rotavirus vaccine. There was no

difference in the mean (SD) (months) age of vaccinated [14.8 (10.6)] and

unvaccinated [14.4 (10.5)] children. Rotavirus positivity was

significantly higher (47%) in unvaccinated than in vaccinated (28.3%)

children (P=0.01). Mean Vesikari score and severe cases were

significantly more in rotavirus positive than in negative children

within unvaccinated group (P<0.001), while these did not differ

within the vaccinated group. Rotavirus strain G1P[8] was identified as

the most prevalent strain in both, vaccinated (60%) and unvaccinated

(72.8%) groups. No association was found between mean Vesikari score and

viral coinfections.

Conclusions: This study suggests decline in

rotavirus positivity in rotavirus-vaccinated children hospitalized for

acute gastroenteritis and high prevalence of G1P[8] and non-rotaviral

co-infections in Pune, Western India.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Diarrhea, Rotavirus vaccine.

|

|

Rotaviruses continue to be the commonest cause of

childhood acute gastroenteritis resulting in an estimated 24 million

outpatients visits, 2.5 million hospitalizations and 450,000 deaths

among children below 5 years of age worldwide [1]. Two rotavirus

vaccines, Rotarix, a monovalent human rotavirus vaccine and RotaTeq, a

pentavalent bovine-human reassortant vaccine have been licensed for use

in several countries including India [2, 3]. With evidence of their high

efficacy and safety in Americas, Europe, Australia and also in low

income countries, World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended their

inclusion in primary immunization programs globally [4,5]. Although

studies to assess immunogenicity and safety of Rotarix and RotaTeq have

been conducted successfully in India [6, 7], they have not yet been

introduced in the national immunization program [8]. However, their use

has been recommended by the Committee on Immunization in Children of the

Indian Academy of Paediatrics [9]. In a representative survey, routine

administration of rotavirus vaccine has been reported to be 9.7% by the

sampled pediatricians of India in 2009-2010 [10].

During the hospital-based rotavirus surveillance

being conducted at National Institute of Virology, Pune, Western India

among children who were hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis in the

years 2013-2014, we compared the demographic and clinical

characteristics, disease severity and virological status of children who

gave the history of rotavirus vaccination and others who did not.

Methods

The criteria for enrolment of children with acute

gastroenteritis and methodology used for clinical assessment and sample

collection have been described earlier [11]. Accordingly, children aged

less than 5 years of age admitted for acute gastroenteritis in three

different hospitals in Pune, India, were enrolled in the study.

Demographic and clinical data inclusive of age, date of onset and sample

collection, duration and maximum number of episodes of diarrhea and

vomiting, signs of dehydration, treatment and outcome of infection were

recorded for all patients. Severity of diarrhea was scored on the basis

of Vesikari scale [12]. Additionally, history of receipt of rotavirus

vaccine was obtained from children enrolled in the study. Efforts were

made to obtain accurate rotavirus vaccination history by referring to

their vaccination records and making phone calls to note the number of

doses, dates of administration and type of the rotavirus vaccine. Stool

samples were collected in sterile screw capped plastic containers and

transported on ice to the laboratory of National Institute of Virology,

Pune for detection of rotavirus antigen and strain characterization.

Prior to the enrolment of a child in the study, informed consent was

obtained from parent(s) or guardian. The study was approved by the

institutional and hospital Ethics Committees.

Ten percent (w/v or v/v) suspension was prepared in

0.01M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.2 from all stool samples.

ELISA was performed on all suspensions using commercially available kit

(Premier Rotaclone, Meridian

Bioscience, Inc. USA) as per manufacturer’s instructions to detect the

presence of rotavirus antigen. The viral nucleic acids were extracted

from 30% (w/v) suspensions of all ELISA positive stool samples using

Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer’s

instructions. The VP7 and VP4 genes were genotyped by multiplex reverse

transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT PCR) according to the

methods described earlier [13-15]. To determine the VP7 and VP4

genotypes of rotavirus strains non-typeable in multiplex PCR, first

round PCR products were sequenced using ABI-PRISM Big Dye Terminator

Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA) and a

ABI-PRISM 310 Genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) after purification

on minicolumns (QIAquick: Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

The presence of noro virus (NoV), enteric adeno virus

( AdV), human astro virus (HAst V) and entero virus (EV) was detected in

the stool specimens collected only from rotavirus-vaccinated children by

amplification of RdRp region A (126 bp), hexon (300 bp) ORF 1a (289 bp)

and 5’NCR (404 bp) regions, respectively as described earlier [16-19].

Statistical analysis: Two proportions were

compared using chi square test, two means were compared using

Mann-Whitney test and disease severity was compared by using chi square

test for 4X2 contingency table. P<0.05 were considered

statistically significant.

Results

Five hundred and twenty nine patients hospitalized

for acute gastroenteritis (from January 2013 to December 2014) at three

hospitals in Pune included 53 children (10%) who had received rotavirus

vaccine and 476 (90%) who had not. Among the vaccinated children, 18.9%,

56.6%, and 24.5% were administered with 3, 2 and 1 doses, respectively

of either of the monovalent (Rotarix) or pentavalent (RotaTeq) vaccines.

Male to female ratio (1.65:1 vs 1.64:1) and their age

distribution (0-6, 7-12, 13-18, 19-24, 25-59 months) were similar in

both groups. The mean (SD) age in months of vaccinated [14.8 (10.6)] and

unvaccinated [14.4 (10.5)] children hospitalized with acute

gastroenteritis was comparable.

Rotavirus positivity was found to be significantly

low (28.3%) in rotavirus vaccine recipients as compared to that of the

non-recipients (47%) (P=0.01) and was higher in males as compared

to females in both groups (P<0.05). The mean (SD) age (mo) in

rotavirus positive children in vaccinated and unvaccinated groups was

comparable [14.9 (9.2) and 13.5 (7.8)] (P>0.05). The same two

groups of rotavirus positive children also showed similar clinical

profile and presentation in terms of fever, history of vomiting and

diarrhea, duration of hospital stay and Vesikari scores (P>0.05)

(Table I).

TABLE I Characteristics of Rotavirus Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Children With and Without Rotavirus Gastroenteritis

|

Variables |

Vaccinated group |

Unvaccinated group |

|

Positive |

Negative |

P value |

Positive |

Negative |

P value |

|

Number |

15 |

38 |

- |

224 |

252 |

- |

|

Gender- Male; n (%) |

9 (60) |

24 (63.2) |

0.83 |

140 (62.5) |

156 (61.9) |

0.89 |

|

Age (mo), Mean (SD) |

14.9 (9.5) |

14.7 (11.1) |

0.79 |

13.5 (7.8) |

15.2 (12.4) |

0.62 |

|

Fever (≥37.10C), Mean

(SD) |

38.2 (0.3) |

38.1 (0.6) |

0.67 |

38.1 (0.6) |

38.3 (0.7) |

0.06 |

|

Vomiting |

|

Present: No. (%) |

14 (93.3) |

20 (52.6) |

0.005 |

205 (91.5) |

179 (71) |

<0.001 |

|

Duration (d), Mean (SD) |

1 .79 (1.1) |

1.65 (1.2) |

0.6 |

1.97 (1.0) |

2.16 (1.3) |

0.30 |

|

Episodes/day, Mean (SD) |

6.64 (5.0) |

4.7 (2.8) |

0.3 |

5.24 (3.6) |

4.13 (2.7) |

0.001 |

|

Diarrhea |

|

Duration (d), Mean (SD) |

2.33 (1.0) |

2.26 (1.2) |

0.64 |

2.19 (1.1) |

2.38 (1.1) |

0.13 |

|

Episodes/day, Mean (SD) |

13.13 (4.7) |

8.18 (3.7) |

0.001 |

11.14 (5.5) |

9.22 (5.2) |

<0.001 |

|

Hospital stay (d), Mean (SD) |

3.6 (1.1) |

4.4 (1.6) |

0.19 |

4.07 (1.1) |

4.63 (2.4) |

0.001 |

|

Vesikari score, Mean (SD) |

11.9 (2.4) |

10.5 (3) |

0.11 |

12.3 (2.0) |

11.4 (2.7) |

<0.001 |

|

Disease severity, No. (%) |

|

Mild |

0 |

1 (2.6) |

|

1 (0.4) |

3 (1.2) |

|

|

Moderate |

3 (20) |

18 (44.7) |

0.129 |

35 (15.6) |

89 (35.3) |

<0.001* |

|

Severe |

12 (80) |

17 (44.7) |

|

186 (83) |

145 (57.5) |

|

|

Very severe |

0 |

2 (5.3) |

|

2 (0.9) |

15 (6.0) |

|

Within the group of children who had not received

rotavirus vaccine, mean episodes of vomiting and diarrhea per day and

mean sikari scores were more commonly observed among rotavirus

positive than in rotavirus negative children (P=0.001, P<0.001

and P<0.001, respectively), and duration of hospital stay was

longer in rotavirus negative children than in rotavirus positive

children (P=0.001). Such analysis performed within the vaccinated

group of children showed more occurrences of vomiting and more number of

diarrheal episodes in rotavirus positive than in negative children (Table

I).).

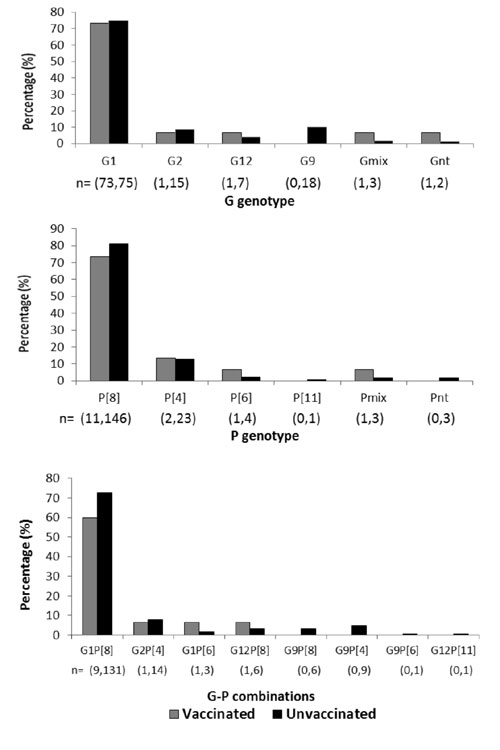

The multiplex PCR performed on rotavirus positive

stool samples showed amplification of VP7 and VP4 genes in 93.3% and

100% of the strains, respectively from vaccinated group and in 98.8% and

98.3%, respectively from unvaccinated group. Among the vaccinated and

unvaccinated groups of children, the most prevalent G and P types were

G1 (73.3% and 75%) and P[8] (73.3% and 81.1%), respectively. Other

genotypes G2, G9, G12, P[4], P[6] and P[11] were detected at low levels

(0 % -13.3%) (Fig. 1a, 1b). Among the

strains typed for both genes, G1P[8] strains were detected at the

highest level in both (60% in vaccinated and 72.85 in unvaccinated)

groups. Frequency of detection of other common or unusual strains that

included G2P[4], G1P[6], G12P[8], G9P[8], G9P[4], G9P[6], and G12P[11]

ranged between 0.0% and 7.8 % (Fig. 1c). Overall

mixed infections of G and P genotypes (G1G9P[4], G1P[6]P[8], G1G9P[8],

G1G9P[4] P[8], G1G2P[8], G2P[4]P[8], and G9P[6]P[8]) were detected in

2.7%-13.3% children in both groups. Only 0.5% of the strains from the

unvaccinated group remained non-typeable for both genes.

|

|

Fig. 1 Distribution of (a) G genotypes

(b) P genotypes and (c) common and unusual G-P combinations in

RVA strains detected in vaccinated and unvaccinated children.

The values in parentheses indicate respectively the number of

children in vaccinated and unvaccinated groups positive for a

particular genotype /G-P combination. Abbreviations - mix and nt

stand for mixed infections and non-typeables, respectively.

Gmix are G1/G2/G9 and Pmix are

P[4]/P[6]/P[8].

|

Stool samples from both rotavirus positive and

negative children from vaccinated group were examined for infections

with other enteric viruses (NoV, AdV, HAstV and EV) known to cause acute

gastroenteritis. Of the 53 children, 24 (45.2%) showed excretion of

single or multiple viruses in the stool. Single infections of NoV, AdV,

AstV and EV were detected in 5.6%, 11.3%, 1.8% and 13.2% respectively.

Mixed infections of rotavirus and other enteric viruses (NoV/ EV /HAstV)

were detected in six children (11.3%). In addition, mixed infections,

one each of EV with HAstV and AdV with HAstV were also detected.

Discussion

The present study reports the characteristics of

rotavirus infections in rotavirus vaccinated and unvaccinated children,

<5 years of age, hospitalized for acute gastroenteritis in Pune, Western

India during 2013-2014. The data of this study indicated that although

the rate of rotavirus vaccination among the enrolled children was only

10%, the vaccine recipients were less likely to have

rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis as compared to the non-recipients.

Further, similar disease severity scores and duration of hospital stay

were recorded in rotavirus positive and negative children in the

vaccinated group. In the unvaccinated group, significantly more severity

score was found in the rotavirus positive as compared to the rotavirus

negative children. In this (unvaccinated) group, longer duration of

hospital stay was noted in the rotavirus negative as compared to the

rotavirus positive children.

Most of the rotavirus-infected children from

unvaccinated group of the present study were below 2 years of age, and

the infections were clustered in post monsoon season as documented

earlier [20]. It has been reported that shifts in the average age and

seasonality pattern of rotavirus disease might take place in post

vaccination period [21]. In the present study, no change in the pattern

of rotavirus infections with respect to specific age and season (data

not shown) was noted in the vaccinated group. Although this finding may

be attributed to incomplete dosage and/or improper schedule followed for

vaccination, the interpretation has limitation due to presence of small

number of children in the vaccinated group.

Earlier reports from other countries have described

rise in the circulation of strains other than the vaccine strains after

the introduction of mono or pentavalent vaccines [22]. Virological

analysis of rotavirus positive stools performed in this study for both

vaccinated and unvaccinated groups was in agreement with the data

reporting diversity in circulating rotavirus strains [23] and

highlighted predominance of G1P [8] strains among both groups. It may be

noted that circulation of diverse rotavirus strains of a single genotype

has been reported continuously in children with acute gastroenteritis

from Pune and other regions of India [24,25]. On this backdrop,

infections with G1P [8] strains need to be delineated by analysis of all

capsid and internal genes. Further, to determine the vaccine induced

pressure on genotypes, it would be necessary to have higher coverage of

vaccination.

Evidence for the field effectiveness of rotavirus

vaccine(s) is highly desired to enhance its eventual country-wide

acceptance and use in the newer target populations. However, current

unavailability of this vaccine in the national immunization program and

its availability at comparatively high cost in the open market in India

restrict its usage as described earlier [10]. Although, the study

findings provide evidence of less likelihood of rotavirus infections in

vaccinated children, it is to be noted that in this study, extent of

vaccination coverage was variable and that the analysis was limited to

the small number of vaccine recipients who represented city based

pediatric population of Western India providing us less than the desired

power for detecting a significant difference in rotavirus disease

acquisition between the groups of vaccine recipients and non-recipients

(78%). However, the leads do indicate a promising role of the rotavirus

vaccine. In view of this, the observations made in this study need to be

ascertained by examination of a large number of rotavirus vaccine

recipients and non-recipients and eventually performing a classical

case-control study to more objectively prove the efficacy of rotavirus

vaccine in the Indian children. With rotavirus vaccine likely to be

rolled out in a step-wise manner in different states of India, a

systematic effort would be required to monitor the rotavirus infections

and genotypes in children presenting with rotavirus vaccine and

carefully document the rotavirus vaccine history to generate the data on

its effectiveness in different regions of country.

Contributors: PJ: Conducted the laboratory tests,

interpreted and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; GV:

Coordinated and organized collection of clinical data and laboratory

work; RG: Recorded demographic and clinical data; VK, RD and AB:

Conducted clinical examination of patients admitted to the hospitals;

SM: Coordinated and monitored the surveillance activity of Pune center

and contributed to manuscript development; SC: Conceived and designed

the study and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Funding: Indian Council of Medical

Research

Competing Interests: None stated.

Acknowledgements: Dr DT Mourya, Director,

NIV, Pune for his constant support and Mr Atul Walimbe for his

assistance in statistical analysis of the data. Technical assistance of

Ms. Kanak Borawake and Mr Vishal Jagtap is gratefully acknowledged.

|

What is Already Known?

• Rotavirus vaccines were found to be

immunogenic with good safety profile in studies conducted in

India.

What This Study Adds?

• Rotavirus positivity is significantly lesser in vaccinated

children admitted with diarrhea in comparison to non-vaccinated

children.

|

References

1. Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD,

Duque J, Parashar UD. 2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated

mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of

universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:136-41.

2. Ruiz-Palacios GM, Pérez-Schael I, Velázquez FR,

Abate H, Breuer T, Clemens SC, et al. Safety and efficacy of an

attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J

Med. 2006;354:11-22.

3. Vesikari T, Matson DO, Dennehy P, Van Damme P,

Santosham M, Rodriguez Z, et al. Safety and efficacy of a

pentavalent human-bovine (WC3) reassortant rotavirus vaccine. N Engl J

Med. 2006;354:23-33.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on

Infectious Diseases. Prevention of rotavirus disease: Updated guidelines

for use of rotavirus vaccine. Pediatrics. 2009; 123:1412-20.

5. Rotavirus vaccines WHO position paper: January

2013 - Recommendations. Vaccine. 2013;31:6170-1.

6. Narang A, Bose A, Pandit AN, Dutta P, Kang G,

Bhattacharya SK, et al. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity and safety

of human rotavirus vaccine (RIX4414) in Indian infants. Hum Vaccine.

2009;5:414-19.

7. Lokeshwar MR, Bhave S, Gupta A, Goyal VK, Walia A.

Immunogenicity and safety of the pentavalent human-bovine (WC3)

reassortant rotavirus vaccine (PRV) in Indian infants. Hum Vaccin

Immunother. 2013;9:172-6.

8. Vashishtha VM, Choudhury P, Kalra A, Bose

A, Thacker N, Yewale VN, et al. Indian Academy of Pediatrics

(IAP) recommended immunization schedule for children aged 0 through 18

years – India, 2014 and updates on immuni-zation. Indian Pediatr.

2014;51: 785-800.

9. Indian Academy of Pediatrics Committee on

Immunization (IAPCOI). Consensus recommendations on immunization, 2008.

Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:635-48.

10. Gargano LM, Thacker N, Choudhury P, Weiss PS,

Pazol K, Bahl S, et al . Predictors of administration and

attitudes about pneumococcal, Haemophilus influenzae type b and

rotavirus vaccines among pediatricians in India: A national survey.

Vaccine. 2012; 30:3541-5.

11. Kang G, Arora R, Chitambar SD, Deshpande J, Gupte

MD, Kulkarni M, et al. Multicenter, hospital-based surveillance

of rotavirus disease and strains among Indian children aged< 5 years. J

Infect Dis. 2009; 200:S147-S53.

12. Ruuska T, Vesikari T. A prospective study of

acute diarrhoea in Finnish children from birth to 2 1/2 years of age.

Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:500-7.

13. Tatte VS, Gentsch JR, Chitambar SD.

Characterization of group A rotavirus infections in adolescents and

adults from Pune, India: 1993-1996 and 2004-2007. J Med Virol. 2010;

82:519-27.

14. Freeman MM, Kerin T, Jennifer H, Caustland KM,

Gentsch J. Enhancement of detection and quantification of rotavirus in

stool using a modified real time RT-PCR assay. J Med Virol.

2008;80:1489-96.

15. Gentsch JR, Glass RI, Woods P, Gouvea V,

Gorziglia M, Flores J, et al. Identification of group A rotavirus

gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;

30:1365-73.

16. Girish R, Broor S, Dar L, Ghosh D. Foodborne

outbreak caused by a Norwalk- like virus in India. J Med Virol.

2002;67:603-7.

17. Allard A, Girones R, Juto P, Wadell G. Polymerase

chain reaction for detection of adenoviruses in stool samples. J Clin

Microbiol. 1990;28:2659-67.

18. Noel JS, Lee TW, Kurtz JB, Glass RI, Monroe SS.

Typing of human astroviruses from clinical isolates by enzyme

immunoassay and nucleotide sequencing. J Clin Microbiol.

1995;33:797-801.

19. Sapkal GN, Bondre VP, Fulmali PV, Patil P,

Gopalkrishna V, Dadhania V, et al. Enteroviruses in patients with

acute encephalitis, Uttar Pradesh, India. Emerg Infect Dis.

2009;15:295-8.

20. Saluja T, Sharma SD, Gupta M, Kundu R, Kar S,

Dutta A, et al. A multicenter prospective hospital-based

surveillance to estimate the burden of rotavirus gastroenteritis in

children less than five years of age in India. Vaccine. 2014;32:A13-9.

21. Patel MM, Steele D, Gentsch JR, Wecker J, Glass

RI, Parashar UD. Real-world impact of rotavirus vaccination. Pediatr

Infect Dis J. 2011;30:S1-S5.

22. Kirkwood CD, Boniface K, Barnes GL, Bishop RF.

Distribution of rotavirus genotypes after introduction of rotavirus

vaccines, Rotarix® and RotaTeq®, into the National Immunization Program

of Australia. Kirkwood CD, Boniface K, Barnes GL, Bishop RF. Pediatr

Infect Dis J. 2011;30:S48-53.

23. Kang G, Desai R, Arora R, Chitamabar S, Naik TN,

Krishnan T, et al. Diversity of circulating rotavirus strains in

children hospitalized with diarrhea in India, 2005-2009. Vaccine.

2013;31:2879-83.

24. Samajdar S, Ghosh S, Dutta D, Chawla-Sarkar M,

Kobayashi N, Naik TN. Human group A rotavirus P[8] Hun9-like and rare

OP354-like strains are circulating among diarrhoeic children in Eastern

India. Arch Virol. 2008;153:1933-6.

25. Kulkarni R, Arora R, Arora R, Chitambar, SD.

Sequence analysis of VP7 and VP4 genes of G1P [8] rotaviruses

circulating among diarrhoeic children in Pune, India: A comparison with

Rotarix and RotaTeq vaccine strains. Vaccine. 2014;32:A75-A83.

|

|

|

|

|