|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53:

575-581 |

|

Expanded Indian National Rotavirus

Surveillance Network in the Context of Rotavirus Vaccine

Introduction

|

|

Sanjay Mehendale, S Venkatasubramanian, CP Girish

Kumar, *Gagandeep

Kang,

#MD Gupte

and #Rashmi Arora

From National Institute of Epidemiology, Chennai;

*Christian Medical College, Vellore; and #Indian Council of Medical

Research, New Delhi; India.

Correspondence to: Dr. Sanjay Mehendale, Director,

National Institute of Epidemiology, Indian Council of Medical Research,

II Main Road, TNHB, Ayapakkam, Chennai – 600077, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: April 24, 2015;

Initial review: July 08, 2015;

Accepted: April 09, 2016.

|

Objective: To extend a

nation-wide rotavirus surveillance network in India, and to generate

geographically representative data on rotaviral disease burden and

prevalent strains.

Design: Hospital-based

surveillance.

Setting: A comprehensive

multicenter, multi-state hospital based surveillance network was

established in a phased manner involving 28 hospital sites across 17

states and two union territories in India.

Patients: Cases of acute diarrhea

among children below 5 years of age admitted in the participating

hospitals.

Results: During the 28-month

study period between September 2012 and December 2014, 11898 children

were enrolled and stool samples from 10207 children admitted with acute

diarrhea were tested; 39.6% were positive for rotavirus. Highest

positivity was seen in Tanda (60.4%) and Bhubaneswar (60.4%) followed by

Midnapore (59.5%). Rotavirus infection was seen more among children aged

below 2 years with highest (46.7%) positivity in the age group of 12-23

months. Cooler months of September – February accounted for most of the

rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis, with highest prevalence seen

during December – February (56.4%). 64% of rotavirus-infected children

had severe to very severe disease. G1 P[8] was the predominant rotavirus

strain (62.7%) during the surveillance period.

Conclusions: The surveillance

data highlights the high rotaviral disease burden in India. The network

will continue to be a platform for monitoring the impact of the vaccine.

Keywords: Epidemiology; Rotavirus diarrhea,

Vaccine.

|

|

Diarrheal diseases account for 1 in 10 child

deaths worldwide, making diarrhea the second leading cause of deaths

among children under the age of 5 years [1]. Rotavirus infections are

the most common cause of severe gastroenteritis in children below 5

years of age worldwide and account for 5% of all deaths among children

in this age group [2]. Nearly 453,000 (420,000 – 494,000) child deaths

were estimated to have occurred globally during 2008 due to rotavirus

infection with 22% in children below five years of age in India alone

[3]. Recent estimates have shown that about 872,000 hospitalizations and

78,500 deaths occur due to rotavirus infections annually in India [4].

Several studies on rotavirus disease have been

conducted across different parts of India but due to differences in

study design, operational definitions, populations examined, recruitment

strategies, and detection systems used [5]; information on the national

level on rotavirus diarrhea disease burden is not available.

The ‘National Rotavirus Surveillance Network’ (NRSN)

was established in December 2005 by the Indian Council of Medical

Research (ICMR) to evolve a sustainable surveillance platform to

estimate and monitor the disease burden in children under 5 years of age

hospitalized for diarrhea [5,6]. In order to make informed decisions

regarding possible phased introduction of rotavirus vaccine in the

country as part of the national immunization program, the surveillance

network was expected to generate data on rotavirus disease burden and

monitoring trends over time across the country. Another objective was to

generate data on molecular epidemiology of rotavirus in India. This

network generated valuable data for the period of 2005-2009. The first

round of the NRSN (2005- 2009) was initiated with four laboratories and

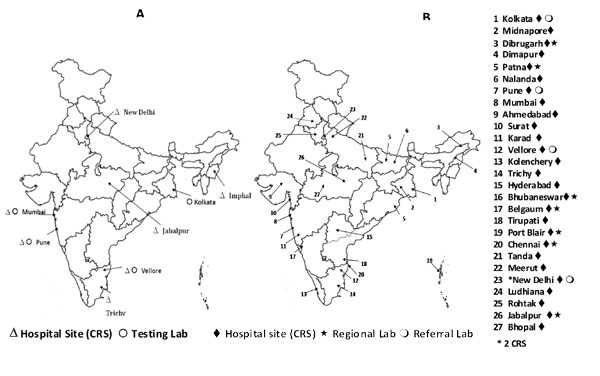

ten hospitals in seven different regions of India (Fig. 1).

The detailed results have been published earlier [5,6]. The analysis of

surveillance data involving over 7000 children demonstrated both the

high prevalence of rotavirus disease in India as well as the circulation

of a diverse range of rotavirus strains [6]. Another notable finding was

the emergence of G12 strains, particularly G12 P[6] strains, in both the

Western and Northern region [5,6].

|

|

Fig. 1 Hospital sites and testing

laboratories (a) 2005 -2009 (b) 2012-2016.

|

In November 2011, the expert advisory group set up by

ICMR recommended expansion to include more clinical surveillance sites

in hospitals and testing laboratories network to have more complete

regional representation of the country. Following this recommendation,

the NRSN was expanded to generate pan-India data on rotavirus disease

burden. The present paper describes the process, methodology and

framework of the expanded network (2012 onwards), and highlights the key

findings and lessons learnt in this endeavor. Detailed analysis of the

surveillance data is published in a separate paper.

Methods

The Expanded National Rotavirus Surveillance Network

(ENRSN) was planned to conduct hospital-based surveillance for rotavirus

from 2009 onwards across the country. The network includes four Referral

and seven Regional laboratories in Southern, Western, Northern and

Eastern/ North-Eastern regions of the country, and 28 clinical

recruitment sites (CRS) of hospitals in 17 states and two Union

Territories with inpatient pediatric facilities that contribute clinical

data and samples. The present ENRSN platform has been built with three

phases of expansion in different parts of India. In Phase-1, the

surveillance was initiated in September 2012 at 8 sites viz.

Vellore (Tamil Nadu), Trichy (Tamil Nadu), Hyderabad (Telangana),

Tirupati (Andhra Pradesh), Ludhiana (Punjab), Kolenchery (Kerala), New

Delhi and Port Blair (Andaman & Nicobar). In September-October 2013, CRS

in 12 cities viz. Kolkata (West Bengal), Midnapore (West Bengal),

Pune (Maharasthra), Mumbai (Maharasthra), Karad (Maharasthra), Tanda

(Himachal Pradesh), Meerut (Uttar Pradesh), New Delhi, Rohtak (Haryana),

Dibrugarh (Assam), Dimapur (Nagaland), Belgaum (Karnataka), Surat

(Gujarat) and Ahmedabad (Gujarat) initiated surveillance as part of the

Phase-2 expansion. In Phase-3, additional sites [Patna (Bihar), Nalanda

(Bihar), Bhubaneswar (Odisha), Chennai (Tamil Nadu), Jabalpur (Madhya

Pradesh) and Bhopal (Madhya Pradesh)] started enrolling children in

surveillance in July - August 2014. The network has been formalized by

signing Memorandum of Understanding (MoUs) between each CRS, affiliated

referral or regional laboratory and the coordinating center. The list of

participating investigators and centers is provided as Annexure

1.

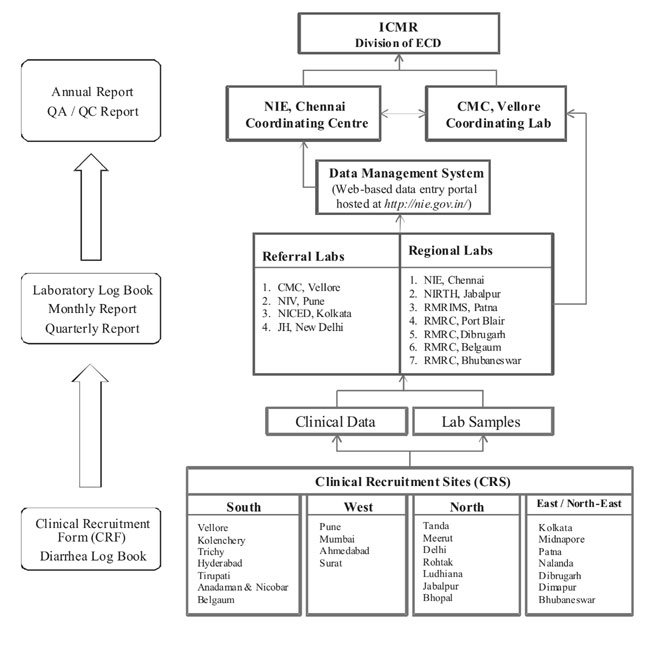

The Epidemiology and Communicable Diseases (ECD)

Division of ICMR is responsible for administrative coordination of the

network, providing funding and leadership to the network. The National

Institute of Epidemiology is the coordinating centers for this

surveillance network involving 28 CRS across the country, and is

responsible for selecting and initiating CRS, training in field

component of the study protocol and data management. Its additional

responsibility includes coordination, monitoring and evaluation as well

as quality control of the clinical component, sample transfers, data

management and analysis. Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore is the

coordinating laboratory that conducts training of laboratory personnel

for laboratory procedures, designs and implements laboratory protocols

and ensures laboratory quality management at all levels.

Clinical/Field Component

Site selection and support: Clinical recruitment

sites (CRS) were identified by the National Institute of Epidemiology

(NIE) with the help of partner institutes (referral and regional

laboratories) in the respective regions viz. South, West, North

and East/ North-East.

Establishing surveillance: The sanctioning and

funding of each CRS and partner laboratories involved completion of

specific documentation and submission to ICMR. The documentation process

included signing of a MoU/ undertaking and obtaining clearance from the

Ethics committees of the concerned hospitals / institutes.

Patient enrolment: All cases of acute diarrhea ( ³3

loose stools in a 24 hour period) and of duration not greater than 5

days among children aged (0-59 months) admitted to the CRS for

supervised oral or intravenous rehydration were considered for

enrollment under ENRSN. Eligible children were enrolled after obtaining

written informed consent from the parents/guardians. Each CRS enrolled

children throughout the year, collected clinical data including history

of rotavirus vaccination on a standardized clinical recruitment

form/case report form (CRF), and also collected stool samples. Records

such as date of admission for diarrhea management and enrolment were

recorded in a diarrhea hospitalization logbook maintained in each CRS.

Sample collection: Whole stool specimen (~5ml)

was collected from each child enrolled in the study and transported

within 2 hours to the testing laboratory or stored at 4 0C

until transportation. Samples stored at 40C

after collection were transported in boxes with ice packs at weekly or

fortnightly intervals to the testing laboratory.

Laboratory Testing

Stool samples were subjected to rotavirus screening

using a commercial enzyme immunoassay (Premier

Rotaclone, Meridian Biosciences) and genotyping

for VP7 (G-typing) and VP4 (P-typing) by Reverse-transcription

polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) [5]. Results of the laboratory

analyses were recorded in a laboratory log book maintained in each

testing laboratory.

Seven regional laboratories carried out ELISA for

rotavirus antigen detection on stool samples collected at affiliated

CRS. The regional laboratories were also responsible for entry of both

clinical and laboratory data. Four referral laboratories carried out

ELISA for screening on samples collected at CRS directly assigned to

them, PCR for genotype characterization (including a subset of rotavirus

positive samples from affiliated regional laboratories), and also

completed data entry. Referral/ Regional Laboratories submitted monthly

and quarterly reports. The organizational framework and data flow in the

network is described in Fig. 2.

|

|

Fig. 2 Sample and data flow in

National Rotavirus Surveillance Network.

|

Training: Each referral and regional laboratory

conducted hands-on training for staff recruited for the surveillance

activity covering the three main components of the ENRSN program;

namely, clinical, sample management, laboratory analysis and data entry.

Quality assurance: The coordinating laboratory at

CMC, Vellore in coordination with NIE sent pretested panels of positive

and negative samples to all the participating laboratories annually.

Similarly CMC received set of ten consecutively tested samples for

retesting from all the laboratories bi-annually. A panel of public

health and child health experts constituted by ICMR in coordination with

NIE carried out periodic monitoring visits to all levels of the network.

Data management: In the expanded round of NRSN a

comprehensive, web-based data management system was introduced by NIE.

The features of this system include double data entry, validation,

innovative data matching interface, record level blocking and efficient

data export to NIE, the Coordinating Center for ENRSN. The

details of the data management framework have been described elsewhere

[8]. Regional and referral laboratories were responsible for the data

entry of the CRFs. Diarrheal disease severity was calculated using the

Vesikari score [5]. Data validation and analysis was carried out at NIE.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed to

assess the proportions of rotavirus-positive cases in terms of

demographic factors, seasons, regions, disease severity and genotype

distribution using SPSS 17.0.

Results

During the 28-month study period from September 2012

to December 2014, a total of 14315 children with acute gastroenteritis

were admitted to the participating hospitals and 11898 children were

enrolled in to the surveillance. Among the 10207 children from whom

stool samples were collected and analyzed, 39.6% were positive for

rotavirus (Table I). The highest rotavirus positivity was

seen in Tanda (60.4%) and Bhubaneswar (60.4%), followed by Midnapore

(59.5%). The lowest prevalence was observed in Nalanda (3.6%) and Patna

(7.3%). Overall, most of the surveillance sites registered high

proportion of rotavirus positivity.

TABLE I Regional and Site-wise Rotavirus Positivity Rates of Children Hospitalized with Acute Gastroenteritis

|

Region |

CRS |

Admitted/Enrolled* |

Number of Samples Tested# |

Rotavirus N(%) Positive#

|

|

East |

Kolkata |

660/461 |

431 |

228 (52.9) |

|

Midnapore |

918/602 |

592 |

352 (59.5) |

|

Bhubaneswar |

710/411 |

268 |

162(60.4) |

|

Dibrugarh |

356/356 |

279 |

102(36.6) |

|

Dimapur |

326/326 |

260 |

117(45.0) |

|

Patna |

528/309 |

301 |

22(7.3) |

|

Nalanda |

244/230 |

169 |

6(3.6) |

|

Total |

3742/2695 |

2300 |

989(43.0) |

|

West |

Pune |

532/469 |

368 |

204(55.4) |

|

Mumbai |

453/415 |

369 |

133(36.0) |

|

Ahmedabad |

306/304 |

231 |

58(25.1) |

|

Surat |

540/508 |

424 |

169(39.9) |

|

Karad |

447/433 |

363 |

125(34.4) |

|

Total |

2278/2129 |

1755 |

689(39.3) |

|

South |

Vellore |

1088/957 |

789 |

240(30.4) |

|

Kolenchery |

790/709 |

529 |

239(45.2) |

|

Trichy |

331/324 |

282 |

141(50.0) |

|

Hyderabad |

756/410 |

388 |

93(24.0) |

|

Tirupati |

447/444 |

433 |

117(27.0) |

|

Belgaum |

290/280 |

255 |

80(31.4) |

|

Port Blair |

966/966 |

910 |

385(42.3) |

|

Chennai |

320/281 |

226 |

64(28.3) |

|

Total |

4988/4371 |

3812 |

1359(35.7) |

|

North |

Tanda |

352/272 |

245 |

148(60.4) |

|

Meerut |

332/321 |

282 |

56 (19.9) |

|

Delhi |

1488/1209 |

1070 |

550(51.4) |

|

Rohtak |

501/269 |

246 |

86(35.0) |

|

Ludhiana |

479/477 |

384 |

136(35.4) |

|

Jabalpur |

79/79 |

65 |

13(20.0) |

|

Bhopal |

76/76 |

48 |

16(33.3) |

|

Total |

3307/2703 |

2340 |

1005(42.9) |

|

Total |

14315/11898 |

10207 |

4042(39.6) |

|

*Data from hospital records; # data from

validated data analysis. |

Prevalence of rotavirus positivity in gastroenteritis

was 38.1% (1890/4962) among children below one year of age; whereas the

highest rotavirus disease burden was seen among children between 12-23

months (46.7%; 1514/3244). There was no significant difference in

rotavirus positivity rates by gender. Pooled data analysis of seasonal

prevalence showed that rotavirus infections were seen more commonly

during the cooler months (September – February). The highest prevalence

was observed during December – February (56.4%; 1668/2959) and lowest

during June – August (20.6%; 461/2239). Diarrheal disease severity

analysis among rotavirus-infected children revealed that 64% (2585/4042)

of rotavirus infected children had severe or very severe disease.

Genotype analysis of a subset of rotavirus positive samples showed that

G1 P [8] was the predominant strain (62.7%; 1579/ 2519). Clear history

of rotavirus vaccination was available for only 3.3% (340/10206) of

children.

Discussion

The prevalence of rotaviral diarrhea among Indian

children aged less than 5 years included in ENRSN (September 2012 to

December 2014) was 39.6%. This is in conformity with the findings of the

earlier round of NRSN (2005-2009) [5,6]. Inclusion of fewer hospital

sites in the first phase of surveillance (2005-2009) limited the

generalizability of the surveillance findings due to limited

geographical representation.

The notable improvements in ENRSN included more

involvement of government medical colleges / facilities which has led to

capacity building in these centers for undertaking surveillance

activities. All the project staff has been trained, and they are

following identical protocols for enrolment, sample collection, clinical

and laboratory procedures, and data management. The CRF has been modeled

on the online data entry platform in the current round of surveillance.

The CRF has been made simpler and more user friendly and data on

rotavirus vaccination history and dosage is being systematically

collected. Through regular supervision and monitoring, focus is being

given on quality management across the network.

The limitation associated with this hospital-based

surveillance program was its inability to generate community-level

disease burden data. Moreover, despite establishing a large network of

28 hospital sites across the country, some states are still outside the

coverage of the network.

Only a small proportion of children attending various

hospitals in the network had history of rotavirus vaccination.

Commercial rotavirus vaccines are available in India since 2007-2008,

and rotavirus vaccine is part of the optional vaccines recommended by

the Indian Academy of Pediatrics. The high price of these vaccines drove

them out of reach of the common man restricting their usage to a small

proportion of children from affluent sections of Indian society. This

may be one reason why a substantially large population of children

continued to get infected and consequently developed severe diarrhea. It

is anticipated that the launch of indigenous rotavirus vaccine in the

national immunization program may result in substantial reduction in the

morbidity and mortality associated with rotaviral gastroenteritis in the

country, especially in areas with high rotavirus diarrhea burden.

Possible linkages between ENRSN and other

surveillance networks in India like hospital-based sentinel surveillance

of bacterial meningitis would result in better implementation and

coordination of one or more surveillance programs in the same hospital

setup. The network platform at various levels viz. district,

state or regional levels, could cater to hypothesis generation for

commissioning satellite studies for locally relevant issues. Besides

surveillance for rotavirus, the ICMR supported ENRSN also offers

appropriate infrastructure to conduct facility-based surveillance for

other related pathogens and supplementary studies such as economic

analysis and cost-effectiveness studies related to vaccine introduction.

In future, ENRSN will provide a unique opportunity

for assessment of impact of vaccination on rotavirus disease in

post-rotavirus vaccine introduction in India in a phased manner by

estimating rotavirus disease burden, severity of disease, circulating

genotypes as well as vaccine related severe adverse events like

intussusception. A pilot retrospective case-record based survey for

intussusception has been carried out involving several hospitals in

Chennai (unpublished report), and efforts are on to conduct a larger

multi-site survey and surveillance for intussusception using the ENRSN

network platform. The surveillance is currently ongoing in 19 states/

UTs and newer hospital sites in states outside the coverage of the

network will also be considered for inclusion to generate micro-level

data on rotaviral disease burden in future.

Contributors: SMM: Network coordination,

manuscript conceptualization and writing; SV and CPGK: contributed to

network coordination, and manuscript writing; GK: Coordinated laboratory

activities in the network and provided intellectual inputs for

manuscript writing; MDG and RA: Coordination at ICMR level and provided

intellectual inputs to for manuscript writing. All authors approved the

final manuscript.

Funding: Indian Council of Medical

Research; Competing interests: None stated.

Annexure 1

Participating investigators of National Rotavirus

Surveillance Network [2012 – 2016]

Agarwal A (Netaji SC Bose Medical College & Hospital,

Jabalpur); Aneja S (Kalawati Saran Children Hospital (LHMC) New Delhi);

Anna Simon (Christian Medical College, Vellore); Aundhakar SC (Krishna

Institute of Medical Sciences, Karad); Babji S (Medical College, Vellore

and Infant Jesus Hospital, Trichy); Bavdekar A (KEM Hospital, Pune);

Baveja. S (Lokmanya Tilak Municipal GH & Medical College, Mumbai); Bhat

J (National Institute for Research in Tribal Health, Jabalpur); Biswas D

(Assam Medical College & Hospital, Dibrugarh); Bora CJ (Assam Medical

College & Hospital, Dibrugarh); Borkakoty B (Regional Medical Research

Centre, Dibrugarh); Chatterjee S (Midnapore Medical College, Midnapore);

Chaudhary S (Dr. Rajendra Prasad Government Medical College, Tanda);

Chawla-Sarkar M (National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases,

Kolkata); Chitambar SD (National Institute of Virology, Pune); Das P

(Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna); Das

VNR (Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna);

Desai K (Surat Municipal Institution of Medical Education & Research,

Surat); Dhongade R (Sant Dnyaneshwar Medical Education & Research

Centre, Pune); Dwibedi. B (Regional Medical Research Centre,

Bhubaneswar); Dwivedi R (Kamla Nehru Hospital, Gandhi Medical College,

Bhopal); Dzuvichu K (District Hospital, Nagaland); Ganguly N (Institute

of Child Health, Kolkata); Gathwala G (Pt. B.D.Sharma PGIMS, Rohtak);

Ghosh C (Midnapore Medical College, Midnapore);Gopalkrishna V (National

Institute of Virology, Pune); Gupta DS (Surat Municipal Institution of

Medical Education & Research, Surat); Jadhav AR (Lokmanya Tilak

Municipal GH & Medical College, Mumbai); Jali S (Jawaharlal Nehru

Medical College, Belgaum); Kalrao VR (Bharati Vidyapeeth Medical

College, Pune); Kar SK (Regional Medical Research Centre, Bhubaneswar);

Khuntia HK (Regional Medical Research Centre, Bhubaneswar); Kumar P (Kalawati

Saran Children Hospital, New Delhi); Kumar S (National Institute for

Research in Tribal Health, Jabalpur); Kumar SS (Pragna Children’s

Hospital, Hyderabad); Lal BG (BJR Hospital, Port Blair); Manglani M (Lokmanya

Tilak Municipal GH & Medical College, Mumbai); Manohar B (Sri

Venkateswara Institute of Medical Sciences, Tirupati); Mathew A (St.

Stephen’s Hospital, Delhi); Mathew MA (MOSC Medical College, Kolenchery);

Mehariya KM (BJ Medical College & Civil Hospital, Ahmedabad); Mishra SK

(Capital Hospital, Bhubaneswar); Narayanan SA (Institute of Child Health

& Hospital for Children, Chennai); Niyogi P (Institute of Child Health,

Kolkata); Panda S (National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases,

Kolkata); Pandey K (Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of Medical

Sciences, Patna); Patankar M (BJ Medical College & Civil Hospital,

Ahmedabad); Purani CS (BJ Medical College & Civil Hospital, Ahmedabad);

Ray P (Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi); Roy S (Regional Medical Research

Centre, Belgaum); Sahoo GC (Rajendra Memorial Research Institute of

Medical Sciences, Patna); Singh N (National Institute for Research in

Tribal Health, Jabalpur); Singh P (Surat Municipal Institution of

Medical Education & Research, Surat); Singh T (Christian Medical

College, Ludhiana); Sundari S (Institute of Child Health & Hospital for

Children, Chennai); Temsu T (District Hospital, Nagaland); Thakur AK (Nalanda

Medical College & Hospital, Nalanda); Topno RK (Rajendra Memorial

Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna); Upadhyay A (Lala Lajpat

Rai Memorial Medical College, Meerut); Utpalkant Singh (Child Care

Centre, Patna); Vijayachari P (Regional Medical Research Centre, Port

Blair).

.

|

What is Already Known?

•

First phase of rotavirus

surveillance in India (2005-09) documented the rotavirus disease

burden at selective sites in the country.

What This Study Adds?

•

Expanded National Rotavirus Surveillance Network validates

the findings of the previous surveillance, highlights the high

prevalence (39.6%) of rotavirus disease burden across the

country, and documents baseline national level data at the point

of rollout of rotavirus vaccine in the national immunization

program.

|

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global

Diarrhea Burden. Available from: www.cdc.gov/healthy

water/global/diarrhea-burden.html#one. Accessed March 21, 2015.

2. Tate JE, Chitambar S, Esposito DH, Sarkar R,

Gladstone B, Ramani S, et al. Disease and economic burden of

rotavirus diarrhea in India. Vaccine. 2009;27:F18-24.

3. World Health Organization. Rotavirus Mortality

Estimates. Available from:

www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/estimates/rotavirus/en.

Accessed March 21, 2015.

4. John J, Sarkar R, Muliyil J, Bhandari N, Bhan MK,

Kang G. Rotavirus gastroenteritis in India, 2011-2013: Revised estimates

of disease burden and potential impact of vaccines. Vaccine.

2014;32:A5-9.

5. Kang G, Arora R, Chitambar SD, Deshpande J, Gupte

MD, Kulkarni M, et al. Multicenter, hospital-based surveillance

of rotavirus disease and strains among Indian children aged <5 years. J

Infect Dis.2009;200: S147–S53.

6. Kang G, Desai R, Arora R, Chitamabar S, Naik TN,

Krishnan T, et al. Diversity of circulating rotavirus strains in

children hospitalized with diarrhea in India, 2005–2009. Vaccine.

2013;31:2879-83.

7. Girish Kumar CP, Venkatasubramanian S, Kang G,

Arora R, Mehendale S, for the National Rotavirus Surveillance Network.

Profile and trends of rotavirus gastroenteritis in under five

children in India (2012 – 2014): preliminary report of the Indian

National Rotavirus Surveillance Network. Indian Pediatr. 2016.53:

8. Ravi M, Venkatasubramanian S, Girish Kumar CP,

Arora R, Mehendale S. Online Data Management System for National

Rotavirus Hospital Based Surveillance Network (NRSN) 2013. Available at

www.nie.gov.in/ezine/ezine2.3/technofile.php#link1. Accessed

March 21, 2015.

|

|

|

|

|