|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51: 571-574 |

|

Antimicrobial Prophylaxis for Children with

Vesicoureteral Reflux

Source Citation: The RIVUR Trial

Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2014;doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401811

|

|

|

|

Summary

This is a multi-centric randomized controlled trial

[1] comparing cotrimoxazole prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis in

children (<6 years old) with vesico-ureteral reflux (VUR) detected after

a first or second episode of urinary tract infection (UTI). The trial

was designed to determine efficacy in preventing recurrence of UTI and

renal scarring, as well as antibiotic resistance patterns. It was

conducted across 19 sites in the United States, recruiting subjects over

nearly five years, with follow-up for at least two years. Among 86%

children who completed the study, the investigators observed lower

recurrence of UTI in the intervention group (14.8%) in comparison to

controls (27.4%). Intention-to-treat analysis showed similar results but

lesser magnitude of difference (25.5% vs 37.4%). However, there

was no difference in the incidence of renal scarring (new scarring or

worsening of pre-existing scarring); 11.9% and 10.2% in the intervention

and control groups, respectively. The prevalence of antibiotic

resistance increased significantly with prophylaxis. The investigators

concluded that antibiotic prophylaxis is useful to prevent repeat

episodes of UTI in children with VUR.

Commentaries

Pediatric Nephrologist’s Viewpoint

The RIVUR trial conducted in North America randomized

607 children aged below 6 years, with VUR grades I-IV, after a UTI, to

receive either trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole or placebo for 2 years [1].

Thirty-nine of 302 children on prophylaxis had UTI as compared to72 of

305 children on placebo [relative risk 0.55 (95% CI, 0.38 to 0.78)].

Benefits were more in children with febrile index UTI and in those with

bladder-bowel dysfunction (BBD). There was no difference in renal

scarring between the two groups. More children on prophylaxis (63%) than

on placebo (19%) had resistant isolates.

A very small number of boys (9%) were enrolled,

limiting applicability of its results to boys. While primary VUR is

commonly reported in girls, such huge gender disparity has not been

shown outside US [2-4]. This is important as boys did not benefit from

prophylaxis in the Swedish study [4]. Results of subgroup analyses (with

reasonable number of subjects and event rates) show that effect of

prophylaxis was not significant in grade III-IV VUR and in absence of

BBD. Thus it seems that prophylaxis is beneficial to a distinct patient

population comprising of girls with low grade reflux and BBD.

Increasingly, VUR is recognized as a heterogeneous condition with

regional and genetic differences [5]. It appears from this trial that

prophylaxis would reduce morbidity related to UTI but not long-term

consequences of renal scarring (hypertension, renal failure) at the cost

of increased antimicrobial resistance. A prudent way forward will be

that the use of prophylaxis is based on risk-stratification rather than

mere presence of reflux.

Pankaj Hari

Department of Pediatrics, AIIMS, New Delhi, India.

[email protected]

Pediatric

Surgeon’s Viewpoint

The present study proves the supremacy of

antimicrobial prophylaxis over watchful waiting approach for patients

with grade I to grade IV VUR. Of the grades of VUR studied, the

pediatric surgeons and pediatric urologists are usually involved in the

management of children with grade IV VUR. For lower grades of VUR, we

are consulted only when there are repeated episodes of breakthrough

infections, or when there are issues about non-compliance. One of the

shortfalls of this study is to study grades I to IV VUR together. The

authors should have studied patients with grades I and II, and those

with grades III and IV reflux, separately. Second, there is no mention

whether those patients with bladder and bowel dysfunction had any

urodynamic studies, or had concomitant bladder and bowel dysfunction

management. For the patients with grade III and IV reflux, surgical

correction and endoscopic management of VUR should also have been added.

An earlier study [6] – also referred by the authors of this paper –

documented that the incidence of pyelonephritis was significantly higher

in the medical group than the surgical group [6]. Endoscopic management

is known has equivocal results in comparison to surgical correction in

grades III and IV VUR [7]. So, the management of VUR should entail as

follows: Grade I and II – antimicrobial prophylaxis or watchful waiting,

Grade III and IV – endoscopic managemen,t and Grade V – surgical

correction. RIVUR trial data is relevant mainly for group I and II VUR.

Yogesh Kumar Sarin

Department of Pediatric Surgery, MAMC,

New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

Evidence-based-medicine Viewpoint

Relevance: It is reported that UTI occurs

in 8-10% girls and 2-3% boys during infancy and childhood [8,9], with 5%

risk of recurrent infections and renal scarring [10] that may be

associated with long-term complications, including hypertension and

chronic renal disease [11]. Children with VUR are at increased risk of

recurrent infections and more serious consequences [12]. Therefore,

recent national [13] and international [14] guidelines recommend

screening for VUR and antibiotic prophylaxis after the first confirmed

episode of UTI. However, a previous exploration of evidence [15], did

not demonstrate reduction of recurrence of UTI with antibiotic

prophylaxis, in children with or without VUR. Two systematic reviews

[16,17] also did not find strong evidence of benefit in either group of

children. Against this backdrop, this RCT [1] is both relevant and

timely.

Critical appraisal: This study is an

example of a well-designed and well-conducted randomized trial. There

was appropriate allocation sequence generation and blinding. Multiple

outcomes were determined, with stringently defined UTI being the primary

outcome. No urine bags were used for specimen collection. Follow-up

nuclear scans for renal scarring were also read by pediatric nuclear

medicine experts. The sample size was calculated a priori, and

almost 86% children could be followed up for the primary outcome.

Follow-up duration was sufficiently long to record development of the

relevant outcomes. Data were analyzed as per protocol as well as by

intention-to-treat analysis. Although compliance to prophylaxis was less

than perfect, it probably matches the pattern in real-life. Overall, the

study is a methodologically high-quality trial, with low risk of bias.

Based on these characteristics, it should be

relatively easy to accept the reported findings, especially as it is in

line with other recent well-designed studies [18,19]. The difficulty

arises on two fronts: (i) the overall significance of the new data in

this trial, and (ii) its implications for practice.

The two Cochrane reviews [16,17] did not demonstrate

statistically significant reduction in risk of recurrence of UTI in

children with VUR, but these excluded a couple of large relevant trials

[4,19]. This necessitates a fresh meta-analysis pooling data from the

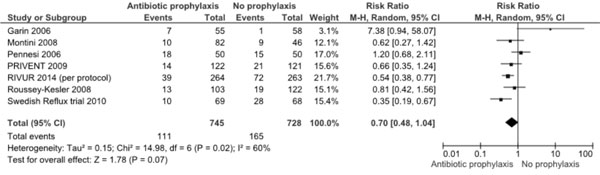

missed trial and the current RCT [1], which shows (Fig. 1)

that the relative risk of recurrence of UTI with prophylaxis is 0.70

(95% CI 0.48, 1.04; 7 trials, 1473 participants) when the

per-protocol data of new RCT are included. Re-analysis using ITT

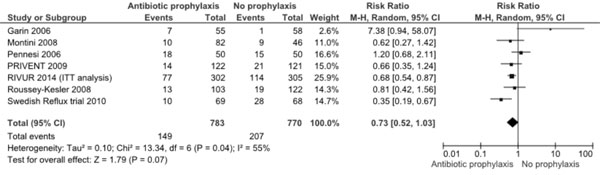

data (Fig.2) shows almost similar results [RR 0.73

(95% CI 0.52, 1.03; 1553 participants). These data suggest that despite

this large well-designed study, the evidence is still equivocal and does

not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of prophylaxis,

although there is a trend in this direction.

|

|

Fig. 1 Meta-analysis of antibiotic

prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for prevention of UTI

recurrence (including RIVUR 2014 per protocol data).

|

|

|

Fig 2: Meta-analysis of antibiotic

prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for prevention of recurrence

of UTI (including RIVUR 2014 intention-to-treat analysis of

data).

|

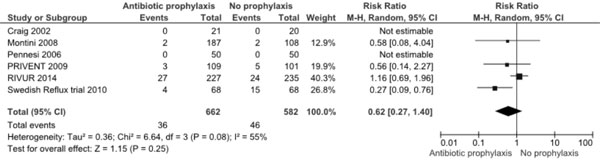

Further, both Cochrane reviews and the current RCT

clearly showed that antibiotic prophylaxis did not prevent development

of renal scarring. Fresh meta-analysis (Fig. 3) including

the new data also confirms this (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.27, 1.40; 6 trials,

1244 participants). This appears surprising because reduction in UTI

would be expected to reduce long-term scarring and its compli-cations.

Absence of this benefit calls for search of other more effective

approaches to manage VUR. In this context, recent experience with

dextranomer/hyaluronic acid polymer to treat VUR (20) is promising. In a

series with 54 children (81 VUR units), treatment resolved VUR in 72

(89%). Renal scarring remained status quo or regressed in 75%. If this

modality becomes routine, the management paradigm may shift from

watchful waiting with prophylaxis. Another important reason to lean away

from prophylaxis is the associated increase in prevalence of

antibiotic-resistant bacteria over time (>25% in this RCT), and episodes

of UTI caused by resistant bacteria (>65%). This suggests that

cotrimoxazole prophylaxis cannot be continued indefinitely. Fresh

research is required to study the pattern with antibiotic rotation

regimens.

|

|

Fig. 3 Meta-analysis of antibiotic

prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for prevention of new or

worsening renal scarring

|

Extendibility: There are several reasons

that the data from this study can be extended to the Indian setting. UTI

is fairly common, although appropriate diagnosis using stringent

criteria and appropriate urine collection methods, need improvement. E.

coli is the most commonly isolated organism in children [21], and

Cotrimoxazole the most commonly chosen agent for prophylaxis. On the

other hand, not all centers have access to modalities for detecting VUR

and/or renal scarring. In such settings, should physicians continue

prescribing prophylaxis (hoping for reduced recurrence of UTI but being

aware that it increases risk of episodes with resistant organisms, and

has no benefit on scarring) or abandon the practice altogether.

Unfortunately, current high quality evidence does not resolve the issue,

and may necessitate a well-designed RCT in Indian children.

Joseph L Mathew

Department of Pediatrics,

PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

Email: [email protected]

References

1. The RIVUR Trial Investigators. Antimicrobial

prophylaxis for children with vesicoureteral reflux. N Engl J Med. 2014;

May 4. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Hannula A, Venhola M, Renko M, Pokka T, Huttunen

NP, Uhari M. Vesicoureteral reflux in children with suspected and proven

urinary tract infection. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1463-9.

3. Nakai H, Kakizaki H, Konda R, et al;

Prospective Study Committee of Reflux Nephropathy Forum, Japan. Clinical

characteristics of primary vesicoureteral reflux in infants: multicenter

retrospective study in Japan. J Urol. 2003; 169:309-12.

4. Brandström P, Esbjörner E, Herthelius M,

Swerkersson S, Jodal U, Hansson S. The Swedish reflux trial in children:

III. Urinary tract infection pattern. J Urol 2010;184:286-91

5. Williams G, Fletcher JT, Alexander SI, Craig JC.

Vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:847-62.

6. Weiss R, Duckett J, Spitzer A. Results of a

randomized clinical trial of medical versus surgical management of

infants and children with grades III and IV primary vesicoureteral

reflux (United States). The International Reflux Study in Children. J

Urol. 1992;148(5 Pt 2):1667-73.

7. Benoit RM, Peele PB, Docimo SG. The

cost-effectiveness of dextranomer/hyaluronic acid copolymer for the

management of vesicoureteral reflux: 1: substitution for surgical

management. J Urol. 2006;176:1588-92.

8. DeMuri GP, Wald ER. Imaging and antimicrobial

prophylaxis following the diagnosis of urinary tract infection in

children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:553-4.

9. Mishra OP, Abhinay A, Prasad R. Urinary infections

in children. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:838-43.

10. Coulthard MG, Lambert HJ, Keir MJ. Occurrence of

renal scars in children after their first referral for urinary tract

infection. BMJ. 1997;315 918-9.

11. Najar MS, Saldanha CL, Banday KA. .Approach to

urinary tract infections. Indian J Nephrol. 2009;19:129-39.

12. Hoberman A, Charron M, Hickey RW, Baskin M,

Kearney DH, Wald ER. Imaging studies after a first febrile urinary

tract infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:195-202

13. Indian Society of Pediatric Nephrology,

Vijayakumar M, Kanitkar M, Nammalwar BR, Bagga A. Revised statement on

management of urinary tract infections. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:709-17.

14. Subcommittee on Urinary Tract Infection, Steering

Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Roberts KB. Urinary

tract infection: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and

management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24

months. Pediatrics. 2011;128:595-610.

15. Mathew JL. Antibiotic prophylaxis following

urinary tract infection in children: A systematic review of randomized

controlled trials. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:599-605.

16. Williams G, Craig JC. Long-term antibiotics for

preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in children. Cochrane

Database Syst Rev. 2011;3:CD001534.

17. Nagler EVT, Williams G, Hodson EM, Craig JC.

Interventions for primary vesicoureteric reflux. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 2011;6:CD001532.

18. Craig JC, Simpson JM, Williams GJ, Lowe A,

Reynolds G, McTaggart SJ, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis and

recurrent urinary tract infection in children. New Engl J Med.

2009;361:1748-59.

19. Garin EH, Olavarria F, Garcia Nieto V, Valenciano

B, Campos A, Young L. Clinical significance of primary vesicoureteral

reflux and urinary antibioticprophylaxis after acute pyelonephritis: A

multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:626-32.

20. Garge S, Menon P, Rao KLN, Bhattacharya A, Abrar

L, Bawa M, et al. Vesicoureteral reflux: Endoscopic therapy and

impact on health related quality of life. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg.

2013;18:11-15.

21. Sharan R, Kumar D, Mukherjee B. Bacteriology and

antibiotic resistance pattern in community acquired urinary tract

infection. Indian Pediat. 2013;50:707-8.

|

|

|

|

|