|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2014;51:

539-543 |

|

INCLEN Diagnostic Tool

for Epilepsy (INDT-EPI) for Primary Care Physicians:

Development and Validation

|

|

Ramesh Konanki, Devendra Mishra, Sheffali Gulati,

Satinder Aneja, Vaishali Deshmukh,

Donald Silberberg, Jennifer M Pinto, Maureen Durkin, Ravindra M Pandey,

MKC Nair,

Narendra K Arora and INCLEN Study Group*

From the Inclen Trust International, New Delhi, India

Correspondence to: Dr Narendra K Arora, Executive

Director, The Inclen Trust, International, F1/5, Okhla Industrial Area,

Phase-1, New Delhi, India.

Email: nkarora@inclentrust.org

Received: April 03, 2013;

Initial review: May 08, 2013;

Accepted: February 14, 2014.

*INCLEN Study Group: Core Group:

Alok Thakkar, Arun Singh, Gautam Bir Singh, Manju Mehta, Manoja K Das,

Monica Juneja, Nandita Babu, Paul SS Russell, Poma Tudu, Praveen Suman,

Rajesh Sagar, Rohit Saxena, Savita Sapra, Sharmila Mukherjee, Sunanda K

Reddy, Tanuj Dada, Vinod Bhutani. Extended Group:

AK Niswade, Archisman Mohapatra, Arti Maria, Atul Prasad, BC Das,

Bhadresh Vyas, GVS Murthy, Gourie M Devi, Harikumaran Nair, JC Gupta, KK

Handa, Leena Sumaraj, Madhuri Kulkarni, Muneer Masoodi, Poonam Natrajan,

Rashmi Kumar, Rashna Dass, Rema Devi, Sandeep Bavdekar, Santosh Mohanty,

Saradha Suresh, Shobha Sharma, Sujatha S Thyagu, Sunil Karande, TD

Sharma, Vinod Aggarwal, Zia Chaudhuri.

|

Objective: To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of

a new diagnostic instrument for epilepsy – INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for

Epilepsy (INDT-EPI) – with evaluation by expert pediatric neurologists.

Study design: Evaluation of diagnostic test.

Setting: Tertiary care pediatric referral centers

in India.

Methods: Children aged 2-9 years, enrolled by

systematic random sampling at pediatric neurology out-patient clinics of

three tertiary care centers were independently evaluated in a blinded

manner by primary care physicians trained to administer the test, and by

teams of two pediatric neurologists.

Outcomes: A 13-item questionnaire administered by

trained primary care physicians (candidate test) and comprehensive

subject evaluation by pediatric neurologists (gold standard).

Results: There were 240 children with epilepsy

and 274 without epilepsy. The candidate test for epilepsy had

sensitivity and specificity of 85.8% and 95.3%; positive and negative

predictive values of 94.0% and 88.5%; and positive and negative

likelihood ratios of 18.25 and 0.15, respectively.

Conclusion: The INDT-EPI has high validity to

identify children with epilepsy when used by primary care physicians.

Keywords: Childhood neuro-developmental disorders,

Resource-limited settings, Psychometric evaluations.

Keywords: Efficacy, Immunization, Neisseria meningitidis,

Protection, Vaccine.

|

|

Epilepsy contributes to significant morbidity with

reported prevalence of 2.4-5.6 per 1000 in India [1-3]. However, nearly

75% of these do not receive appropriate treatment [4], many due to a

lack of proper diagnosis. The situation is no different in other

developing countries [5-9]. The reported rate of misdiagnosis of

epilepsy among pediatricians ranges from 30-39% [10-13]. The diagnosis

of epilepsy is mostly based on clinical history supported by neuro-imaging

and electroencephalography. In the absence of an objective "gold

standard" diagnostic test, the decision of a team of experienced

pediatric neurologists with access to all investigations may be

considered as nearest to the "gold standard" for diagnosis of childhood

epilepsy [14].

As per 2003 estimates, the Indian populations of over

1 billion were being served by only about 500 neurologists [4,15] most

of whom serve in large cities. Similarly, most pediatricians are also

concentrated in urban areas while the majority of Indians still live in

the villages and small towns where such expertise is not available. The

most effective way to reduce the treatment gap of people with epilepsy

in developing countries is delivery of epilepsy services through primary

health care [16]. Hence, there is a need to for a diagnostic instrument

for use by primary care physicians to help them in identifying cases

with epilepsy as well as ruling out non-epileptic events. There are no

comprehensive, validated tools that can be administered by such

physicians for diagnosis of epilepsy. The INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for

Epilepsy (INDT-EPI) has been developed with the major aim of increasing

the access to care for seizure disorders of large segments of

populations residing in rural areas and small towns where specialists

care may not be available. The present study was conducted to evaluate

the psychometric properties of this new instrument for childhood

epilepsy as part of a nation-wide, multi-centre prevalence study for

common neuro-developmental disorders among children aged 2-9 years.

Methods

This diagnostic test evaluation study was conducted

on children attending the pediatric neurology outpatient clinics of

three public sector tertiary care pediatric referral centers [All India

institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Lady Hardinge Medical College

(LHMC) and Maulana Azad Medical College (MAMC)] in New Delhi, India.

These centers receive referred cases for complex medical problems as

well as simple ailments seen at primary care level, mostly from National

Capital Region and nearby states. Children (2-9 years) of either gender

attending the pediatric neurology outpatient clinics were eligible for

inclusion in the study. Children who had poor general condition

requiring admission (e.g. respiratory distress requiring supplemental

oxygen, altered sensorium, peripheral circulatory collapse, suspected

sepsis and bleeding), and those who were not accompanied by a primary

caregiver were excluded from the study. At each study site, a team of

two pediatric neurologists with at least three years experience in the

diagnosis and management of epileptic children, one study coordinator

and one graduate (MBBS) physician participated in the study. Ethical

approval was obtained from IndiaCLEN Review Board and the Institutional

Review Board of all the study sites. The instrument development and data

collection were done from January 2008 to April 2010.

Diagnostic instruments

Gold standard: The diagnosis of epilepsy was

established at each site by consensus of the two pediatric neurologists

following detailed history and physical examination with access to

electroencephalogram, computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance

imaging of Brain, as indicated. The instrument included a summary

assess-ment (diagnosis): ‘epilepsy’, ‘epilepsy with other neuro-developmental

disorder (NDD)’, "NDDs other than epilepsy" and "No NDD/Epilepsy".

Candidate test: INDT-EPI which has been

developed on the standard definitions of seizures and epilepsy proposed

by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) [17] through

consensus among multidisciplinary national and international team of

experts (49 national and 6 international).

Instrument Development

The INDT-EPI was developed as consensus clinical

criteria (CCC) for diagnosing epilepsy by the Technical Advisory Group

(TAG) consisting of pediatricians, developmental pediatricians, child

psychiatrists, pediatric neurologists, pediatric otorhinolaryngology,

community physicians, clinical psychologists, special educators,

specialist nurses, speech therapists, occupational therapists, and

social scientists through a series of discussions and meetings using

Delphi method and over three rounds of 2-day workshops.

INDT-EPI included questions in simple language to

elicit the history of common seizure types (generalized and partial

motor seizures, absence seizures and myoclonic seizures) (questions

1,2,10,11), the number of seizures and duration between first and last

seizures is captured through question 3 and 4, provoked seizures such as

febrile seizures, seizures occurring during neuro-infections, with head

trauma or during systemic illnesses (question 5 for febrile seizures, 6

for acute symptomatic seizures, 7 for neonatal seizures) and seizure

mimics such as breath holding spells (question 8) and syncopal attacks

(question 9). Question 12 and 13 are final diagnosis. The instrument was

translated from English to Hindi and back translated to English before

the study was undertaken. The Hindi instrument was pretested in 20

children to look for difficulties in administering/understanding the

questions and time needed to complete assessment. The instrument is

available as Web Appendix I.

Enrolment and assessments

Enrolment was done through systematic random

sampling. Two computer-generated random numbers were provided to the

study coordinator daily in a sealed envelope. The first number (between

1 and 9) determined the starting point, and the second random number

(between 5 and 15) determined the nth number (sample interval) to be

sampled starting from the first random number. Every nth child in the

age group of 2-9 years was assessed for eligibility and enrolled after

obtaining written, informed consent from the primary caregiver

until the final sample was achieved. If consent or inclusion criterion

was not achieved, (n+1)th child was enrolled. The day’s enrollment

stopped once 15 children were enrolled in above manner or OPD

registration was over, whichever happened first. Consecutive study

subjects were enrolled in the above manner until desired number of

children were identified based on gold standard diagnosis. Since the

subjects were recruited from pediatric neurology outpatients, stoppage

of recruitment was linked to achieving desired sample of children with

‘no epilepsy’ and ‘no NDD’.

At all three sites, subjects were first administered

the INDT-EPI (candidate test) by the primary care physician and later

evaluated by the expert team of pediatric neurologists (gold standard).

Administration of INDT-EPI took approximately 30-40 minutes.

These findings were filled in a predesigned instrument, enclosed in

separate sealed, opaque envelop bearing the subject’s unique

identification number and handed over to the coordinator. The sealed

envelopes of expert team (gold standard) were opened at the end of day

by the coordinator, who was not part of the assessment team to enlist

the number of cases of epilepsy, epilepsy with other neuro-developmental

disorders (NDDs), NDDs other than epilepsy, and group with no epilepsy

or NDDs, based on the gold standard assessments.

Sample size: Assuming sensitivity and specificity

of INDT-EPI to be 85% with relative precision of 10% at 95%

confidence level, sample size was calculated to be 68 in each category.

To account for drop-outs, it was decided to enrol at least 80 children

in each category (epilepsy, epilepsy with other NDD, NDDs other than

epilepsy, and group with no epilepsy or NDD).

Training and quality assurance: INDT-EPI training

manual for administration and caregiver’s response interpretation was

prepared. General physicians were trained (eight hours of didactic

manual-based teaching and instrument administration on five cases each)

by pediatric neurologists during a two-day comprehensive, hands-on,

structured workshop.

The team of pediatric neurologists (gold standard)

was blinded to the assessment of the physician (candidate test). The

study coordinator at the site assessed children attending the

out-patient clinic for eligibility and enrolled them after taking

written, informed consent from the primary caregiver, but did not take

part in any of the assessments.

Statistical analysis: The data were analyzed

using STATA version.10. The utility and psychometric properties of

INDT-EPI were calculated in comparison with the assessments by the team

of pediatric neurologists.

Results

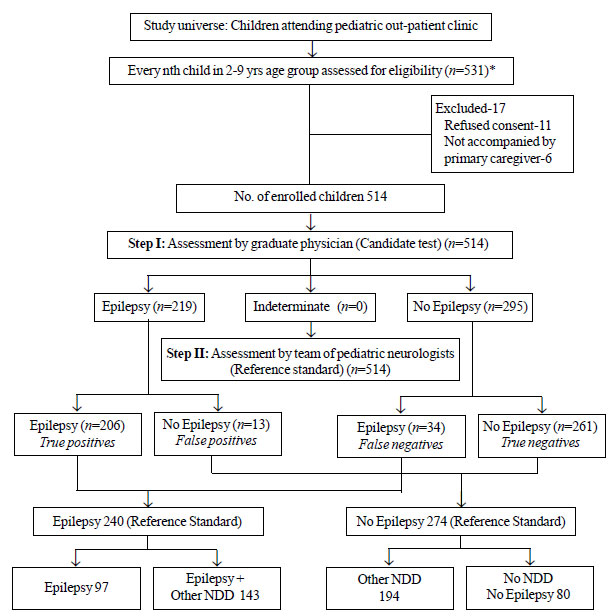

Out of 531 children assessed for eligibility, 514

(341 boys) were included; 11 children refused consent and 6 were not

accompanied by primary caregiver. Mean (SD) age of included children was

60.1 (1.0) months. Of the 240 children with epilepsy, 97 (40%) had only

epilepsy, and 143 (60%) had epilepsy with NDDs according to gold

standard. Of 274 children without epilepsy, 194 (71%) had NDDs other

than epilepsy, and 80 (29%) had no NDDs. Fig. 1 details

the study flow. Out of 240 children with epilepsy, 203 (84%) had

generalized or focal motor seizures, 12 (5%) had absence seizures, and

16 (6.6%) had myoclonic. The team of neurologists could not assign a

clear classification to 9 children. Table I details

the performance of INDT-EPI instrument in comparison to the gold

standard. The possible reasons for the false diagnoses (4.7% false

positives and 14.2% false negatives) by the candidate test are

summarized in Web Table I and

Web Table II.

|

|

Fig. 1 The study plan.

|

TABLE I Psychometric Properties of INCLEN Diagnostic Tool for Epilepsy (INDT-EPI)

|

Sensitivity

|

85.8 (80.8-90.0) |

Specificity

|

95.3 (92.0-97.4) |

|

LR of positive test |

18.2 (10.6-30.8) |

LR of negative test |

0.15 (0.11-0.20)

|

|

Positive predictive value |

94.0 (90.6-96.8) |

Negative predictive value

|

88.5 (84.3-91.9) |

LR: Likelihood ratio; All values in %(95% CI).

|

Discussion

INDT-EPI for diagnosis of childhood epilepsy by the

primary care physician demonstrated good psychometric properties. To the

best of our knowledge, there are no validated instruments for diagnosing

epilepsy. The tools currently available include screening

questionnaires, with confirmation done by specialists [1,18-24].

Differentiating children with epilepsy from those

with other NDDs like cerebral palsy and intellectual disability

(overlapping symptomatology) is often challenging. The specificity of

INDT-EPI increased to 97.4% when it was administered to children with

other NDDs. The specificity of the instrument in subgroup of children

without any NDD was lower (90%) compared to subgroup with other NDDs

(97.4%). It is possible that parents of normal children are less likely

to be forthcoming in terms of thoughtful responses than parents of

children with other NDDs. This can also be attributed to different

health seeking behavior of the parents.

In an earlier study assessing the nature of multiple

events (epileptic or non-epileptic), it was seen that 4.6% children with

non-epileptic events were initially misdiagnosed as having epilepsy

(false positive) and 5.6% children with epilepsy were initially

diagnosed as having ‘no epilepsy’ (false negative) [14]. The assessments

in that study were comprehensive including detailed evaluation by a

panel of pediatric neurologists supported by electroencephalography and

neuro-imaging, when required. In the present study, the assessments were

done by graduate physicians trained to administer the structured

clinical instrument. The rate of false positives in the current study is

comparable to the above-mentioned study and is much lower compared with

the reported rates of misdiagnosis of epilepsy [10,11,13]. To minimize

the misclassification of epilepsy as acute symptomatic seizures (neuro-infections,

head trauma, and systemic illness), clear-cut definitions with durations

can be introduced for defining the seizures occurring in ‘close’

temporal association with brain infections as highlighted by the recent

ILAE guidelines [17,25]. With the addition of duration cut-off to define

acute symptomatic seizures, the sensitivity of the INDT-EPI is likely to

increase.

Limitation of the present study was that the included

subjects from the tertiary care referral centers might not be

representative of the community. The 240 patients of epilepsy out of 514

children reflect the referral bias in pediatric neurology outpatients.

The instrument, in its present form, does not have the provision for

differentiating between active and prevalent cases. The primary care

physician has to suspect epilepsy in his/her setting before the tool is

administered; tool should pick up both prevalent as well as active cases

in such situation.

To conclude, INDT-EPI is a useful tool for diagnosis

of childhood epilepsy by non-expert medical pro-fessionals (with

adequate training) in different clinical settings, and for future

epidemiological studies. This instrument can also be used in day-to-day

clinical practice for diagnosing epilepsy by the primary health care

physicians thereby expanding the care for epilepsy patients and reducing

diagnosis management gap in resource-limited settings. Further studies

on the instrument are recommended to assess its performance in different

community and healthcare settings.

Contributors: All authors have contributed,

designed and approved the study. NKA will act as a guarantor for this

work.

Funding: Ministry of Social Justice and

Empowerment (National Trust), National Institute of Health (NIH-USA);

Fogarty International Center (FIH), Autism Speaks (USA); Competing

interests: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• The diagnosis of epilepsy in children

requires evaluation by experienced pediatricians or pediatric

neurologists along with supporting investigations like EEG and

neuro-imaging.

What This Study Adds?

• The INDT-EPI tool for diagnosing epilepsy

has good sensitivity and specificity when used by primary care

physicians with short training.

|

References

1. Mani KS, Rangan G, Srinivas HV, Kalyanasundaram S,

Narendran S, Reddy AK. The yelandur study: A community-based approach to

epilepsy in rural south India–epidemiological aspects. Seizure.

1998;7:281-8.

2. Koul R, Razdan S, Motta A. Prevalence and pattern

of epilepsy (Lath/Mirgi/Laran) in rural Kashmir, India. Epilepsia. 1988;

29:116-22.

3. Radhakrishnan K, Pandian JD, Santhoshkumar T,

Thomas SV, Deetha TD, Sarma PS, et al. Prevalence, knowledge,

attitude, and practice of epilepsy in Kerala, south India. Epilepsia.

2000; 41:1027-35.

4. Sridharan R, Murthy BN. Prevalence and pattern of

epilepsy in India. Epilepsia. 1999; 40:631-6.

5. Gu L, Liang B, Chen Q, Long J, Xie J, Wu G, et

al. Prevalence of epilepsy in the People’s Republic of China: a

systematic review. Epilepsy Res. 2013;105:195-205.

6. Malik MA, Akram RM, Tarar MA, Sultan A. Childhood

epilepsy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2011; 21:74-8.

7. Benamer HT, Grosset DG. A systematic review of the

epidemiology of epilepsy in Arab countries. Epilepsia. 2009; 50:2301-4.

8. Somoza MJ, Forlenza RH, Brussino M, Centurión E.

Epidemiological survey of epilepsy in the special school population in

the city of Buenos Aires. A comparison with mainstream schools.

Neuroepidemiology. 2009; 32:129-35.

9. Calisir N, Bora I, Irgil E, Boz M. Prevalence of

epilepsy in Bursa city center, an urban area of Turkey. Epilepsia. 2006;

47:1691-9.

10. Chadwick D, Smith D. The misdiagnosis of

epilepsy. BMJ. 2002; 324:495-6.

11. Chinthapalli RN. Who should take care of children

with epilepsy? BMJ. 2003; 327:1413.

12. Cockerell OC, Hart YM, Sander JW, Shorvon SD. The

cost of epilepsy in the United Kingdom: an estimation based on the

results of two population-based studies. Epilepsy Res. 1994; 18:249-60.

13. Uldall P, Alving J, Hansen LK, Kibaek M, Buchholt

J. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy in children admitted to a tertiary

epilepsy centre with paroxysmal events. Arch Dis Child 2006;91:219-21.

14. Stroink H, van Donselaar CA, Geerts AT, Peters

ACB, Brouwer OF, Arts WFM. The accuracy of the diagnosis of paroxysmal

events in children. Neurology. 2003; 60:979-82.

15. Krishnamoorthy ES, Satishchandra P, Sander JW.

Research in epilepsy: development priorities for developing nations.

Epilepsia. 2003; 44 Suppl 1:5-8.

16. Carpio A, Hauser WA. Epilepsy in the developing

world. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009; 9:319-26.

17. ILAE Commission Report. The epidemiology of the

epilepsies: future directions. Epilepsia. 1997; 38:614-8.

18. Placencia M, Sander JW, Shorvon SD, Ellison RH,

Cascante SM. Validation of a screening questionnaire for the detection

of epileptic seizures in epidemiological studies. Br J Neurol. 1992;

115:783-94.

19. Bharucha NE, Bharucha EP, Bharucha AE, Bhise AV,

Schoenberg BS. Prevalence of epilepsy in the Parsi community of Bombay.

Epilepsia. 1988; 29:111-5.

20. Gourie-Devi M, Gururaj G, Satishchandra P,

Subbakrishna DK. Neuro-epidemiological pilot survey of an urban

population in a developing country. A study in Bangalore, south India.

Neuroepidemiology. 1996; 15:313-20.

21. Osuntokun BO, Adeuja AO, Nottidge VA, Bademosi O,

Olumide A, Ige O, et al. Prevalence of the epilepsies in Nigerian

Africans: a community-based study. Epilepsia. 1987; 28:272-9.

22. Anand K, Jain S, Paul E, Srivastava A, Sahariah

SA, Kapoor SK. Development of a validated clinical case definition of

generalized tonic-clonic seizures for use by community-based health care

providers. Epilepsia. 2005; 46:743-50.

23. Das SK, Biswas A, Roy T, Banerjee TK, Mukherjee

CS, Raut DK, et al. A random sample survey for prevalence of

major neurological disorders in Kolkata. Indian J Med Res. 2006;

124:163-72.

24. Banerjee TK, Ray BK, Das SK, Hazra A, Ghosal MK,

Chaudhuri A, et al. A longitudinal study of epilepsy in Kolkata,

India. Epilepsia. 2010; 51:2384-91.

25. Beghi E, Carpio A, Forsgren L, Hesdorffer DC,

Malmgren K, Sander JW, et al. Recommendation for a definition of

acute symptomatic seizure. Epilepsia. 2010; 51:671-5.

|

|

|

|

|