|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2010;47: 599-605 |

|

Antibiotic Prophylaxis Following

Urinary Tract Infection in Children: A Systematic

Review of Randomized Controlled Trials |

|

Joseph L Mathew

Advanced Pediatrics Centre, PGIMER,

Chandigarh 160 012, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

|

Relevance

As many as 2-3% boys and 8-11%

girls are reported to have urinary tract

infection(UTI) during childhood(1,2). Despite rapid

diagnosis and treatment, there is a reported 5% risk

of long term damage(3) owing to recurrence and

consequent renal scarring with its (later)

complications. Therefore, it is customary to

prescribe long term antibiotic prophylaxis following

UTI, irrespective of the presence or absence of

‘risk factors’(4) such as anatomic malformations,

vesico-ureteral reflux (VUR), female gender etc.

Most guidelines recommend prophylaxis in the

management of UTI(5,6). However, data supporting

such recommendations is limited and based on

outdated research; therefore it is relevant to

examine current best evidence on the subject.

This systematic review addresses

the question: "In children with urinary tract

infection (population), does antibiotic

prophylaxis (intervention), prevent

recurrence, renal scarring, long-term complications,

etc (outcome), as compared to no prophylaxis

(comparison)?

Current Best Evidence

Literature search was undertaken

for systematic reviews and randomized controlled

trials (RCT) comparing antibiotic prophylaxis versus

no prophylaxis in children following episode(s) of

UTI, irrespective of underlying renal condition(s).

Trials comparing different antibiotics (against each

other) were not considered. Outcomes of interest

were recurrence of UTI, new or worse renal scarring,

long term complications, cost, and antibiotic

resistance.

Medline search (25 May 2010)

using the Mesh terms for ‘UTI’ and ‘antibiotic

prophylaxis’, with Limits "Meta-Analysis,

Randomized Controlled Trial, Review, All Child: 0-18

years", yielded 66 citations. Simultaneous

Cochrane Library search using "urinary

tract infection AND antibiotic" in "Record

Title", yielded 10 Cochrane reviews/protocols, 4

other reviews, 46 clinical trials, 1 HTA and 4

economic evaluations. Two Cochrane reviews appeared

relevant(7,8). One examined antibiotic

prophylaxis(7), but does not include all currently

available trials; it also combined older trials

(with inappropriate UTI definitions) and recent

trials. The other review(8) examined interventions

for children with VUR only. Non-Cochrane

reviews(9,10) were not up-to-date, necessitating a

fresh systematic review.

Fifteen citations were

shortlisted from the preliminary search and

examination of References for additional trials.

Among these, 10 were excluded for the following

reasons: (i) not RCT (n=4)(11-14), (ii)

definition of UTI not consistent with current

definition (n=3)(15-17), (iii)

cross-over study without randomization

component(18), (iv) trial in children with

VUR but not after UTI(19) and (v) description

of ongoing RCT, but data not available(20). Thus,

data from five RCTs (21-25) comprise current best

evidence.

TABLE I

Characteristics of Included Trials

|

No |

Setting |

Study

design |

Participants |

N

(Px/ No Px) |

Follow-up |

Outcomes |

Ref |

| 1 |

Australia |

MC, DB,

PCT |

N=576

< 18y with >1 episode symptomatic UTI* |

288/288

CTX

(10mg/kg/d) vs

placebo |

Every

3mo × 12 mo |

Recurrence of symptomatic UTI, UTI with fever,

hospitalization for UTI, hospitalization for

other causes, antibiotic for concomitant

illness, scarring, UTI with resistant bacteria,

adverse events |

21 |

| 2 |

France |

MC, RCT |

N=225

1mo-3y with VUR (I-III) diagnosed after UTI**with

CTX sensitive organism |

103/122

CTX (10mg/kg/d) vs

nothing x 18 mo

|

Every 3

mo ×

18 mo |

Recurrence of UTI, symptoms, scarring, VUR

status |

22 |

| 3 |

Italy |

MC, RCT |

N=338

2mo-7y with 1st UTI#

+ VUR (I-III) |

211/127

CTX or CA (15mg/kg/d)

vs nothing |

Every

1-2 mo × 12 mo |

Recurrence of UTI, new renal scarring, adverse

events, recurrence with resistant organism. |

23 |

| 4 |

Italy |

MC, RCT |

N=100<30 mo with VUR (II-IV) diagnosed after 1st

episode of APN† |

50/50

CTX (5-10mg/kg/d) or NF (2mg/kg) vs nothing x 2y |

4 y |

Recurrence of APN, new/worse scarring |

24 |

| 5 |

USA,

Canada, Spain, Peru |

MC, RCT |

N=236

3mo-18 y with APN‡

and VUR (I-III) |

100/118

CTX

(5-10mg/kg/d) or NF

(1.5mg/kg/d) vs nothing |

Every

3mo × 1 y |

Recurrence of UTI, renal scarring |

25 |

|

APN=acute pyelonephritis, BS=bag specimen,

CA=co-amoxyclav, CS=catheter specimen, CFU=colony

forming units, CTX=cotrimoxazole equivalent,

DB=double blinded, FU=follow-up, MC=multicentric,

MSS=mid-stream sample, NF=nitrofurantoin,

PCT=placebo controlled trial, Px=prophylaxis,

SPT=supra-pubic tap, UTI=urinary tract

infection, VUR=vesico-ureteral reflux;

*Defined as symptoms consistent with UTI and

positive culture (any growth of single

pathogenic organism on SPT or ≥104CFU/ml from CS

or ≥105CFU/ml from morning MSS); **Defined as

single organism ≥105CFU/ml from MSS or BS (if

non toilet-trained); #Defined as fever >38 deg

C + pyuria + single organism ≥105 CFU/ml (2

concordant consecutive results); †Defined as

fever of unknown origin + bacteriuria and

leucocytes in urine + ≥106 CFU/ml in two

different samples collected by MSS or CS; ‡Defined as fever, pyuria with

≥ 10WBC/hpf, ≥105 CFU/ml in CS or MSS + scan evidence of APN. |

Table I summarizes the

characteristics of included trials. All used co-trimoxazole

in standard doses; three also included

co-amoxyclav(23) or nitrofurantoin(24,25). Only

one(21) was placebo-controlled. Two trials(22,25)

included only children with VUR; one(24) enrolled

participants after an episode of acute

pyelonephritis. Two trials(21,25) included children

up to 18 years of age. Various outcomes were

examined including recurrence of UTI and scarring.

One trial(24) examined renal scarring, but did not

present results. Risk of bias (Table II)

was low for three trials(21,23,24). The trials

reported sample size calculations; one could not

recruit the planned number(21) and another

calculated sample-size for 70% power(23).

TABLE II

Risk of Bias and Other Design Characteristics of Included Trials (Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool)

|

Trial |

Randomization |

Allocation

concealment |

Blinding |

ITT analysis |

Risk of bias |

Sample size |

Ref |

|

1 |

Adequate |

Adequate |

Adequate |

Yes |

Low |

Yes |

21 |

|

2 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Inadequate |

No |

High |

Yes |

22 |

|

3 |

Adequate |

Adequate |

Inadequate |

Yes |

Low |

Yes (power set at

70%) |

23 |

|

4 |

Adequate |

Adequate |

Partial |

Yes |

Low |

Yes |

24 |

|

5 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Inadequate |

No |

High |

Yes |

25 |

|

ITT = intention-to-treat. |

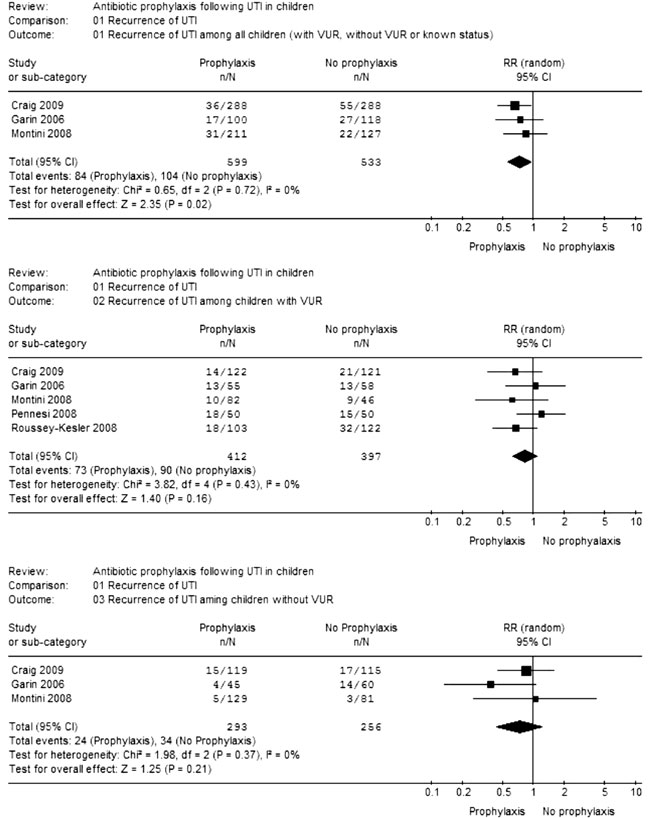

Meta-analysis showed that risk of

UTI recurrence (Fig.1) was reduced

with antibiotic prophylaxis when all children (with

VUR, without VUR and unknown status) were considered

together (RR=0.73; CI=0.56-0.95; 3 trials; 1132

participants; I 2=0%).

However, there was no benefit of prophylaxis when

children with VUR (RR=0.82; CI=0.62-1.08; 5 trials;

809 participants; I2=0%) and without VUR (RR=0.72;

CI=0.43-1.20; 3 trials; 549 participants; I2=0%)

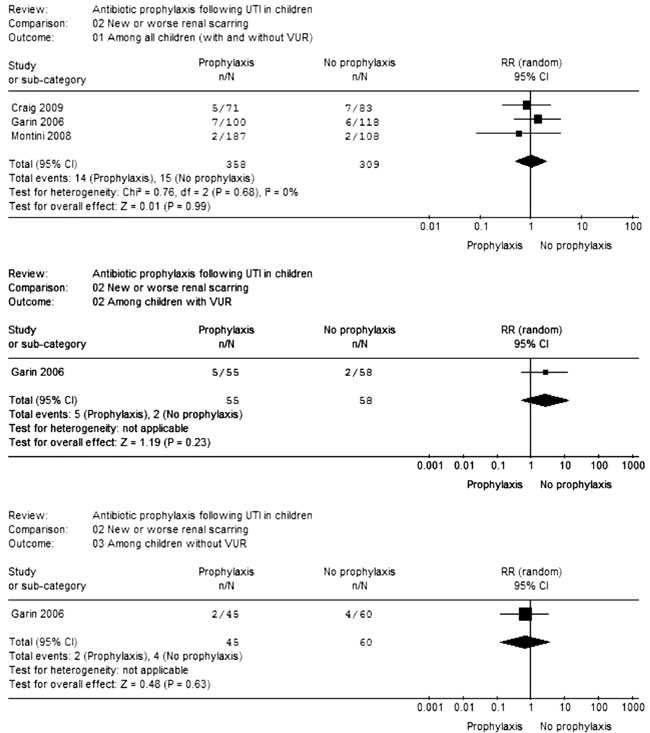

were examined separately. Antibiotic prophylaxis did

not prevent new/worsening renal scarring in children

with VUR (RR=2.64; CI=0.53-13.03; 1 trial; 113

participants), without VUR (RR=0.67; CI=0.13-3.48; 1

trial; 105 participants) and both groups combined

(RR=1.00; CI=0.49-2.03; 3 trials; 667 participants;

I2=0%) (Fig.2). The risk of adverse

events/side effects increased significantly with

antibiotics (RR=3.08; CI=0.02-549.95; 2 trials; 914

participants; I2=92%). Likewise, children on

prophylaxis appeared to have higher risk of UTI

recurrence with a resistant organism (RR=8.60;

CI=0.86-85.81; 3 trials; 190 participants; I2=82%).

|

|

|

Fig.1 Meta-analysis

of data on recurrence of UTI

|

|

|

|

Fig.2

Meta-analysis of data on new/worse renal

scarring. |

Critical Appraisal

Recommendations for antibiotic

prophylaxis following UTI were based on the

expectation of increased risk of recurrence, and

consequent long-term renal damage (through scarring)

including hypertension etc. Supporting data was

limited in quantity (4 RCT with 117 participants)

and (methodological) quality. Additionally, the

trial definitions of UTI are not currently accepted.

Some recent trials with better (though not ideal)

methodology have reported different results,

necessitating better designed RCT and systematic

review of evidence. Examination of current best

evidence also raises the following issues:

The definition of UTI is a

critical issue in RCT of antibiotic prophylaxis; all

the older trials(15-18) defined UTI in a manner not

accepted currently, including some participants

without ‘true’ UTI. In contrast, all the recent

trials(21-25) have used stringent definitions,

reducing the risk of false-positives. Therefore,

combining the older with the recent trials may be

inappropriate.

Is concomitant fever a necessary

component of UTI (to further reduce the risk of

false-positives)? Although this will increase

specificity, in real life, UTI is often treated even

if fever is absent. It can also be argued that with

modern practices of urine specimen collection and

microbiologic criteria for UTI, fever strengthens

the diagnosis, but may not be necessary. Therefore

this review has not looked at symptomatic/febrile

UTI separately.

Should children with and without

VUR be considered separately? The argument in

favour is that the risk of UTI recurrence is higher

with VUR, hence these children should be viewed

differently. The arguments against are that the risk

does not appear to be very different with and

without VUR, the relationship between VUR and renal

scarring is not clear(24), diagnosis is often made

after UTI, and VUR often resolves over time(26,27).

In clinical practice, prophylaxis is often initiated

empirically irrespective of presence/absence of VUR.

Therefore this review has examined antibiotic

prophylaxis separately among children with and

without VUR, and also both groups combined.

Prolonged antibiotic therapy is

not without risk; this includes individual as well

as community risk in terms of adverse events/side

effects and encouraging antimicrobial

resistance(21,23,25). The latter risk has increased

over the decades; therefore justification for

antimicrobial prophylaxis today, should be stricter

than three decades back (when the original trials

were conducted). Based on this, the balance of

current evidence leans away from antibiotic

prophylaxis.

Current evidence is unable to

identify subgroup(s) of children who may benefit

from antibiotic prophylaxis. This is an important

issue because most trials exclude children with

complex congenital malformations and/or higher

grades of VUR (especially V). It is possible that

the balance between benefit and harm of

antimicrobial prophylaxis in children at greater

risk of complications is different from those

included in clinical trials, necessitating

individualized decisions in the absence of evidence.

Therefore, future research should focus on these

specific high(er) risk groups rather than routine

UTI (with or without lower grades of VUR).

Good evidence of the impact of

compliance (or otherwise) to long term prophylaxis

is not available. Lack of compliance could

apparently reduce the beneficial effect of

prophylaxis. Whereas, better compliance during

clinical trials could suggest greater benefit than

in real life (efficacy versus effectiveness).

Extendibility

None of the trials comprising

current best evidence were conducted in our country;

however, there is no reason to suspect that Indian

children behave differently in terms of UTI or risk

of recurrence and/or complications. Hence, the

evidence can be extended to our setting. On the

other hand, the risk of inappropriate antibiotic

usage and consequent antimicrobial resistance could

be a bigger problem in our setting, necessitating

greater caution.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None

stated.

|

EURECA Conclusion in the

Indian Context

• Antibiotic prophylaxis

following UTI does not appear to prevent

recurrence of infection and/or renal scarring

in children with or without VUR, considered

separately.

• Antibiotic prophylaxis could result in

increased risk of recurrence with resistant

organisms.

|

References

1. Hellstrom A, Hanson E, Hansson

S, Hjalmas K, Jodal U. Association between urinary

symptoms at 7 years old and previous urinary tract

infection. Arch Dis Child 1991; 66: 232-234.

2. DeMuri GP, Wald ER. Imaging

and antimicrobial prophylaxis following the

diagnosis of urinary tract infection in children.

Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008; 27: 553-554.

3. Coulthard MG, Lambert HJ, Keir

MJ. Occurrence of renal scars in children after

their first referral for urinary tract infection.

BMJ 1997; 315: 918-919.

4. Hellerstein S. Urinary tract

infections: old and new concepts. Pediatr Clin North

Am 1995; 42: 1433-1457.

5. Bagga A, Babu K, Kanitkar M, Srivastava

RN; Indian Pediatric Nephrology Group, Indian

Academy of Pediatrics. Consensus statement on

management of urinary tract infections. Indian

Pediatr 2001; 38: 1106-1115.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics

Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on

Urinary Tract Infection. Practice parameter: the

diagnosis, treatment, and evaluation of the initial

urinary tract infection in febrile infants and young

children. Pediatrics 1999; 103: 843-852.

7. Williams GJ, Wei L, Lee A,

Craig JC. Long-term antibiotics for preventing

recurrent urinary tract infection in children.

Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 19; CD001534.

8. Hodson EM, Wheeler DM, Smith

GH,Craig JC, Vimalachandra D. Interventions for

primary vesicoureteric reflux. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev 2007; 3: CD001532.

9. Mori R, Fitzgerald A, Williams

C, Tullus K, Verrier-Jones K, Lakhanpaul M.

Antibiotic prophylaxis for children at risk of

developing urinary tract infection: a systematic

review. Acta Paediatr 2009; 98: 1781-1786.

10. Williams G, Craig JC.

Prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in

children. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2009; 22: 72-76.

11. Hoberman A, Keren R.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis for urinary tract

infection in children. New Engl J Med 2009; 361:

1804-1806.

12. Mattoo TK. Are prophylactic

antibiotics indicated after a urinary tract

infection? Curr Opin Pediatr 2009; 21: 203-206.

13. De Cunto A, Pennesi M, Salierno

P. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of

recurrent urinary tract infection in children with

low grade vesicoureteral reflux: Results from a

prospective randomized study. J Urol 2008; 180:

2258-2259.

14. Keren R, Carpenter M,

Greenfield S, Hoberman A, Mathews R, Mattoo T, et

al. Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with

vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing

pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized,

controlled trial. Pediatrics 2008; 122: 1409-1410.

15. Stansfeld JM. Duration of

treatment for urinary tract infections in children.

BMJ 1975; 3: 65-66.

16. Smellie JM, Katz G, Gruneberg

RN. Controlled trial of prophylactic treatment in

childhood urinary tract infection. Lancet 1978; 2:

175-178.

17. Savage DCL, Howie G, Adler K,

Wilson MI. Controlled trial of therapy in covert

bacteriuria of childhood. Lancet 1975; 1: 58-61.

18. Lohr JA, Nunley DH, Howards

SS, Ford RF. Prevention of recurrent urinary tract

infections in girls. Pediatrics 1977; 59: 562-565

19. Reddy P, Evans MT, Hughes PA,

Dangman B, Cooper J, Lepow ML, et al.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis in children with

vesico-ureteral reflux: a randomized study of

continuous therapy vs intermittent therapy vs

surveillance. Pediatrics 1997; 100 Suppl 3: 555-556.

20. Keren R, Carpenter MA, Hoberman

A, Shaikh N, Matoo TK, Chesney RW, et al.

Rationale and design issues of the Randomized

Intervention for Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux

(RIVUR) study. Pediatrics 2008; 122 Suppl 5:

S240-250.

21. Craig JC, Simpson JM, Williams

GJ, Lowe A, Reynolds GJ, McTaggart SJ, et al.

Antibiotic prophylaxis and recurrent urinary tract

infection in children. Prevention of Recurrent

Urinary Tract Infection in Children with

Vesicoureteric Reflux and Normal Renal Tracts (PRIVENT)

Investigators. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1748-1759.

22. Roussey-Kesler G, Gadjos V,

Idres N, Horen B, Ichay L, Leclair MD, et al.

Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of

recurrent urinary tract infection in children with

low grade vesicoureteral reflux: results from a

prospective randomized study. J Urol 2008; 179:

674-679.

23. Montini G, Rigon L, Zucchetta

P, Fregonese F, Toffolo A, Gobber D, et al.

Prophylaxis after first febrile urinary tract

infection in children? A multicenter, randomized,

controlled, noninferiority trial. Pediatrics 2008;

122: 1064-1071.

24. Pennesi M, Travan L,

Peratoner L, Bordugo A, Cattaneo A, Ronfani L, et

al. Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with

vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing

pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized,

controlled trial. Pediatrics 2008; 121: 1489-1494.

25. Garin EH, Olavarria F, Garcia

Nieto V, Valenciano B, Campos A, Young L. Clinical

significance of primary vesicoureteral reflux and

urinary antibiotic prophylaxis after acute

pyelonephritis: a multicenter, randomized,

controlled study. Pediatrics 2006; 117: 626-632.

26. Greenfield SP, Ng M, Wan J.

Resolution rates of low grade vesicoureteral reflux

stratified by patient age at presentation. J Urol

1997; 157: 1410-1413.

27. Schwab CW Jr, Wu HY, Selman

H, Smith GH, Snyder HM 3rd, Canning DA. Spontaneous

resolution of vesicoureteral reflux: a 15-year

perspective. J Urol 2002; 168: 2594-2599.

|

|

|

|

|