Children with a solitary hydronephrotic kidney are

uncommon. We report a patient with severe hypertension associated with a

normally functioning solitary kidney, which showed features of

hydronephrosis.

Case Report

An 8-year-old boy presented with history of headache

for the past eight days and vomiting, fever and neck stiffness for the

past one day. There was no preceding history of seizures, diaphoresis,

palpitations or blurring of vision. The patient was conscious with

minimal neck stiffness, left hemiparesis and blood pressure of 240/160

mm Hg. Fundus examination showed grade 4 hypertensive changes with

papilledema. The blood counts were normal and differential revealed

lymphocytosis. Blood urea level was 36 mg/dL and creatinine was 0.8 mg/dL.

CSF revealed no pleocytosis, normal proteins and no hypoglychorrachia.

Contrast enhanced computed tomography showed minimal meningeal

enhancement with no exudates and a small infarct in the region of right

external capsule. This infarct was a probable sequale of long standing

hypertension.

Hypertension was treated with a combination of

nifedipine (2 mg/kg/day), propranolol (2 mg/kg/day), clonidine (20

µg/kg/day) and furosemide (2 mg/kg/day). His chest skiagram was normal

and ECG showed evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy. Abdominal

ultrasound showed absent left kidney with mild hydronephrosis of the

right kidney; Doppler study showed no evidence of renal artery stenosis.

An intravenous urogram confirmed adequate function of the right kidney.

Plasma renin estimation (4.8 ng/mL/hr) was within normal limits.

Selective renal angiographic study with estimation of renal vein renin

(4 ng/mL/hr) was essentially normal. A DTPA-renal scan showed normal

renal function on the right side with no function on the left. Diuretic

renography done simultaneously, confirmed the presence of nonobstructive

hydronephrosis. Voiding cystourethrogram done did not show evidence of

vesicouretral reflux.

DMSA scan done subsequently had shown no evidence of

scarring consequent to a preexisting reflux. Twenty four hour urinary

catecholamines and I131 MIBG (metiodo-benzyl guanidine) scintigraphy

were normal. CT of the abdomen failed to demonstrate the contralateral

kidney. Cystoscopy done revealed ureteric orifices on both sides. On

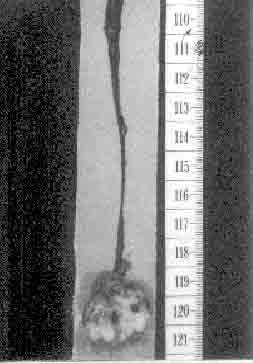

laprotomy a dysplastic atrophic kidney (Fig. 1) was identified on

the left side, which was removed. This however failed to ameliorate the

hypertension. Immunoturbidometric examination of the urine showed micro-albuminuria

(24 mg/g creatinine).

|

| Fig. 1.

Grossly atrophic kidney removed on laprotomy. |

Discussion

Severe hypertension posed a diagnostic dilemma.

Ultrasound, Doppler study plasma renin levels, urinary catecholamines

and MIBG scan ruled out renovascular hyper-tension and pheochromocytoma.

Imaging modalities suggested a solitary functioning right kidney with

agenesis of the left kidney. CT failed to pick up any renal tissue on

the left side. Diuretic renogram ruled out pelvi-uretcric obstruction

causing right hydro-nephrosis. Presumably, volume overload on the

solitary functioning kidney resulted in hydronephrosis. Vesico-ureteric

reflux was ruled out on imaging studies. Therefore, the right kidney did

not have a "surgically treatable" cause of hypertension. This left us

with one important question - was the left kidney really absent or

present but dysplastic? A faint suggestion came up on the angiography

that showed a small beaking from the left side of the aorta at the usual

location of the ostium of the left renal artery. Cystoscopy contributed

by visualizing the left ureteric orifice. This settled the issue of

agenesis verses dysplasia. On surgical exploration the lower part

of the ureter was identified and followed upwards leading to the

dysplastic kidney. Looking at the specimen grossly being just 1.5 cm and

disorganized, it is not surprising that CT and ultrasound could not pick

it up pre-operatively. The dysplastic left kidney was removed because

hypertension, infection, hemorrhage and malignant change are known

complica-tions of renal dysplasia(1). There have been reports of

improvement in hypertension following nephrectomy of the dysplastic

kidney. The chances of complete regression of hypertension after

nephrectomy are low, the possibility of reduction in the doses of

antihypertensive drugs is a definitive goal.

Bachmann has presented case reports wherein blood

pressure normalized after removal of the small kidney and in few where

hypertension persisted(2). He emphasized that nephrectomy of the small

kidney should only be performed, if the integrity of the contralateral

kidney is certain.

Hypertension in patients with solitary kidney have

appeared in literature. Lan, et al. collected data on 14 children

with unilateral renal agenesis defined by cystoscopy of which 21% had

hydronephrosis.They observed that this group had increased prevalence of

hyper-tension, proteinuria and renal insufficiency to the tune of 29%,

43% and 36%, compared to the uninephrectomized group. In their study the

incidence of the congenital solitary kidney (CSK) was 1 in 1,496. They

observed that these complications were common in the age group of 30 to

60 years, unlike our patient who presented in the first decade(3).

The cause of hypertension in a child with solitary

kidney has been extrapolated from animal studies and later confirmed in

humans. Laboratory studies show that a marked reduction (11/12) in renal

mass results in progressive glomerulosclerosis of the residual tissue,

manifested by azotemia, proteinuria and hypertension. Glomerular

destruction appears to be due to augmented trans capillary hydraulic

pressure difference (DP) and glomerular plasma flow, a process of

chronic hyperfilteration that leads to altered charge and size selective

permeability, increased trans capillary protein flux, mesangial

overloading and sclerosis(4). CSK is an experiment of nature, in which

the stimulus exists in fetal life, the remnant kidney being enlarged.

The first suggestion that the solitary kidney might be prone to focal

glomerulosclerosis (FGS) was provided by Kiprov, et al.(5). A

foreunner of FSGS is microalbuminuria. The renal function may however

remain stable for a long time.

It is also important to follow up these children,

prevent protein overloading and retard the development of FGS(6). The

incidence of finding a grossly atrophic kidney in a child is as high as

1 in 1400, therefore it is important that such children are identified

and followed up stringently.

Contributors: Sk and UJ were involved in patient

care, analysis of the case and drafting the manuscript. SKM was the

overall incharge of the patient management. SKA operated upon this

patient and helped in drafting the manuscript. UJ will act as guarantor

for the paper.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None stated.