Anita Tandon, Siddarth Ramji, Sudershan Kumari, Alka Goyal, Deepak Chandra

and V.R. Nigam

From the Neonatal Division, Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical

College and Kalawati Saran Children's Hospital, New Delhi 110 001 and

Neonatal Division, Department of Pediatrics,

Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi 110 002, India.

Reprint requests: Dr. Sudershan Kumari, 23 B/6, Guru Gobind Singh Marg,

New Delhi 110 005, India.

Manuscript received: February 21, 1997; Initial review completed:

April 23, 1997;

Revision accepted: December 8, 1997.

Abstract:

Objective: To evaluate the intellectual, psychoeducational and social maturity of a cohort of

unimpaired asphyxiated survivors beyond 5 years of age. Design: Case control study on hospital based cohorts on a longitudinal follow up at High Risk and Well Baby Clinics of a teaching hospital. Methods: The demographic data of these children was recorded. A detailed physical examination was performed. The tests of cognition included the Stanford Binet and the Raven's Progressive matrices. Academic achievement was evaluated by the Wide range achievement test - Revised (WRAT-R). Assessment of visuo-motor integration was done by the Bender Gestalt Test. The proportion of children having soft neurological signs was determined. Vineland Social Maturity Scale was performed on all children. Results: Fifty-four asphyxiated and 57 matched control children participated in the study. Of the 54 asphyxiated children, 27 were tested at a mean age of 7.2 ±1.6 years (Group 1) and 27

were tested at a mean age of 10.9

± 1.52 years (Group 2). The asphyxiated children as a group performed in the normal range on tests of cognition and academic achievement but were significantly disadvantaged (p < 0.005) as compared to controls. A higher percentage of asphyxiated children had low scores on the Bender Gestalt Test as compared to controls but the difference was not significant. A significantly higher proportion of asphyxiated children of both the groups showed the presence of soft neurological signs as compared to controls. Approximately 11% of the asphyxiated children performed in the abnormal range in the Vineland Social Maturity Scale. Conclusion: Cognitive abilities of asphyxiated children beyond the age of 5 years are impaired in comparison to controls, emphasizing the need for early detection and referral for special education.

Key words: Birth asphyxia, Cognition.

PERINATAL asphyxia is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the first year of life. The survivors have long been recognized to have an increased risk of handicaps such as cerebral palsy, mental retardation, epilepsy, deafness and visual

impairment in early childhood. However, with advances in perinatal care, there has been an increase in the non-impaired survivors.

The Apgar score(1) is widely accepted. as a means of assessing the severity of birth

asphyxia. Several studies have shown a significant correlation between low Apgar score at one minute(2-5) and the incidence of neurological abnormality in survivors. These longitudinal studies have primarily focussed on motor sequelae

and early developmental quotients. However, the out- come of unimpaired asphyxiated children has not been well documented in older children, particularly in the context of developing countries. These children are expected to have more school related difficulties as compared to normal children(6). This study was therefore designed to evaluate intellectual, psycho. educational and social maturity of survivors with moderate-severe asphyxia (Apgar

≤ 6 at 1 minute) beyond 5 years of age.

Subjects and Methods

The subjects were selected for evaluation from a cohort of term asphyxiated babies who were being followed longitudinally in the High Risk Clinic of our hospital. Entry criteria included term neonates who had an Apgar 6 at 1 minute and .were between 5 and 13 years without any physical, auditory or visual

impairment at the time of selection. Twenty-seven of these were examined

at a mean age of 7.2±1.6 years (Group 1) and 27 were examined at a mean age of 10.9±1.52 years (Group 2). Fifty 'seven non-asphyxiated healthy term infants, who were born and being followed in the Well Baby Clinic of the same hospital were selected as controls. The age at examination was comparable 10 that of the test subjects.

The assessment measures utilized for evaluating the cognitive abilities

are summarized in Table I. The Indian adaptation of

the Stanford Binet and the Vineland Social Maturity scale were used by us. The Raven's Progressive Matrices and the Bender Gestalt are performance tests and

are culture free. The Wide Range Achievement Test was the only test used unadapted

as there are no standardized tests available for reading, spelling and

arithmetic for the Indian population. Six of the asphyxiated children

and 7 of the controls could not perform this test as they were not well versed with the English language and were hence excluded from the analysis of this test.

All the psychometric tests were standardized and conducted with the help of one of the authors (VRN) who is a Child Psychologist. They were' administered to the children individually in a quiet room.

,

The entire assessment of a child took about Ph-2 hours. A few children

had to be assessed on two or three different occasions. Family information of the, children included birth order, family size, level of maternal

education, socio-economic status and school difficulties. The family information and the parent's

questionnaires were administered by one of the authors (AT). Follow-up communication was through mailing to family, telephone calls or contact person.

Statistical Analyses

The cases and controls were compared with respect to all the outcome measures. Data was processed and analyzed on IBM compatible PC/XT using the EPI-Info Program. Differences in distribution were analyzed by Student's 't' test for normally distributed data or otherwise with Kruskal Wallis Test. Differences in proportion were analyzed by using the Chi-square test with Yate's correction or the Fisher Exact Test if the sample size was small.

Results

Profile

of Subjects

A total of 54 asphyxiated and 57 control children participated in the study. Since the

age range was wide, hence for the purpose of analysis, the asphyxiated and the control children were divided into two groups: (i) Group 1: tested at a mean a of 7.24±1.1 years (range 5-9 years); and (ii) Group 2: tested at a mean age of 10.9±1.22 years (range 9-13 years). Of the 54 asphyxiated children, 6 children had well controlled

seizures and 1 child had arrested hydrocephalus at the time of enrollment.

TABLE

I

Assessment Measures Utilized.

1. Test of Cognition:

(a) Stanford Binet (Indian Adaptation (7): Measures the intelligence in children (Mean IQ

=

100

± 15).

(b) Raven's Progressive Matrices(8): This tests the problem solving ability. A performance IQ

can be obtained from this test (Normal range between 25-75th percentile and Mean IQ 100±15).

2.

Test

of Academic Achievement:

Wide range achievement test

-

Revised (WRAT

-

R)(9) consists of three sub tests: reading, spelling and arithmetic. Standard scores are obtained for each of the three subtests (mean 100±15).

3. Tests

of Motor

Function:

(a) Bender Gestal(10):

Measures integration of visual perception and motor behavior. Scoring

is done by the method as described by Elizabeth Koppitz(11).

(b) M.E. Hertzig:

Method of assessment of Non focal neurological signs(12). It consists of 10

subtests that test gait, balance, bilateral coordination, upper limb co-ordination and

muscle tone. Presence of more than two signs is taken as significant.

4. Social Maturity:

(a) Vineland Social Maturity Scale(13) (Indian Adaption):

This tests the personnel and social proficiency of the child. The test was administered to the parent who was most familiar with the child's behavior (usually the mother). This test is applicable to both handicapped and non-handicapped children. |

Table II shows the demographic data of both asphyxiated and control children. There were no significant differences in social class, maternal education, birth weight and gestation between the two groups.

Psychometric Tests

The results of these tests are summarized in Tables III & IV.

Group 1: On the tests of cognition, the asphyxiated children though

scoring in the normal range did less well as compared to the control

group. The mean IQ in the asphyxiated group was 106.7 as compared to 116.3 in controls (p<0.05). Nearly 19% of the asphyxiated children scored below the 25th centile in Raven's Progressive Matrices as compared to none of the controls. In the WRAT-R, the asphyxiated children did significantly less well as compared to the controls (p < 0.005). In the tests of motor function 41 %of the asphyxiated children showed the presence of non focal neurological

signs as compared to 10% of controls (p < 0.05) and on the Bender Gestalt Test, 33% of the asphyxiated children performed

in the abnormal range as compared to 7.1% of. controls (p<0.05). The

mean social quotient of the asphyxiated children

was 106.6 as compared to 117.6 in controls (p<0.005).

TABLE II

Demographic Data all Asphyxiated and Control Children.

|

Demographic variables |

Group 1

|

Group 2 |

Asphyxia

(n

=

27) |

Control

(n

=

28) |

Asphyxia

(n

=

27) |

Control

(n

=

29) |

|

Mean age of testing (SO) |

7.2 (1.6) |

7.0 (1.2) |

10.9 (1.2) |

10.6 (1.5) |

|

Gender (M:F) |

2.2: 1 |

1.5: 1 |

2.8: 1 |

1:1 |

|

Birth Weight (g) |

2701 |

2859 |

2844 |

2856 |

|

Mean (SD) |

(553.0) |

(363.0) |

(603.0) |

(331.0) |

|

Gestational age (weeks) |

39.27 |

39.60 |

38.88 |

39.89 |

|

Mean (SD) |

(1.92)

|

(1.22)

|

(2.11) |

(0.30) |

|

Social Class No. (%) |

|

. I+II |

15 (56) |

14 (50) |

16 (59) |

15 (52) |

|

. III |

9 (33) |

12 (43) |

9 (33) |

13 (45) |

|

. IV + V |

3 (11) |

2 (70) |

2 (8) |

1 (3) |

|

Maternal Education No. (%) |

|

. < High school |

8 (30) |

6 (21) |

9 (33) |

4 (14) |

|

. Secondary school |

10 (37) |

9 (32) |

10 (37) |

10 (34) |

|

. > Secondary school |

9 (33) |

13 (47) |

8 (30) |

15 (52) |

Group 2: In the tests of cognition, the difference in the two groups was significant (p < 0.005). Thirty per cent of the asphyxiated children scored below the 25th centile on the Raven's Progressive Matrices as compared to 3.4% of controls (p < 0.05). In

the WRA T

-

R also, the asphyxiated children

were clearly disadvantaged in all the 3 subtests as compared to controls

(p < 0.005). In the tests of motor functions 22% of the asphyxiated

children had non focal neurological signs as compared to 3.4% of

controls (p < 0.05) and about 48% performed in the abnormal range on the

Bender Gestalt Test as compared to 21 % of controls (p<0.05). Similarly

the mean social quotient of the asphyxiated children of Group 2 was significantly lower (p<0.005) as compared to the control children.

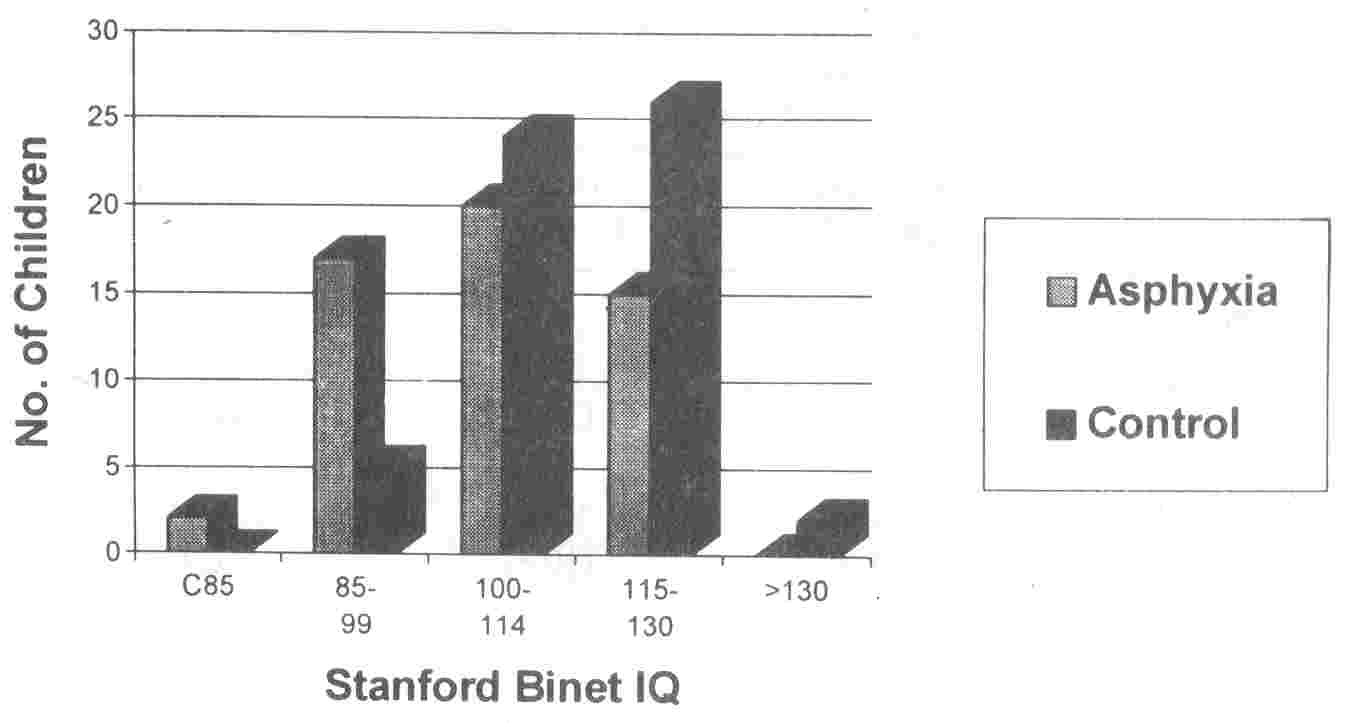

The distribution of Stanford Binet IQ

scores for asphyxiated and control children is illustrated in Fig. 1. A higher proportion of asphyxiated children had an IQ of < 85

(< -1 S.D.) and fewer had IQ of > 115 (> + 1 S.D.) as compared to control children.

Discussion

This study gives the long term outcomes of asphyxiated children (APGAR Score

≤ 6) evaluated at mean age of 7.2 and 10.9 years. Earlier investigators have utilized a variety of laboratory and clinical criteria to make the diagnosis of asphyxia and study its outcome(5,6,14-20). However, amongst these the clinical categorization of neonatal encephalopathy

associated with birth asphyxia(21) has been found to be a more helpful indicator of long term outcome (6,14,15). As our neonatal data pertains Apgar Score, we have analyzed accordingly.

|

|

Fig. 1. Distribution

of

Stanford Binet IQ scores in asphyxiated and control groups. |

Our findings suggest

that the non-impaired asphyxiated children as a

group,

perform in the normal range on tests

of

cognition, academic achievement and social maturity but comparison with socio-demographically matched control children reveals that they are significantly disadvantaged

on nearly every measure tested. The findings of this study are consistent with previous reports of cognitive

deficits and academic achievements(6,14- 17). Robertson et al.(6) reported that the mean IQ scores of non disabled survivors though in the normal range were significantly lower than the mean scores of the comparison group. Similar results were found in the St. Louis prospective study of anoxia(16). The same study(16) also reported that when 33 term 7 year old children who had perinatal

anoxia were com- pared with controls, they had lower scores for

vocabulary and perceptual motor measures but had normal scores for the Bender Gestalt Test and the Embedded Figure Test. Similar results have been reported by the Aberdeen study(18) and by Robertson et al.(15). These findings are comparable to those of our study where though a higher percentage of children performed in the abnormal range on the Bender Gestalt Test, the difference was not significant.

Follow-up studies of selected high risk populations have reported a higher proportion of

minor

neurological abnormalities in

low birth weight infants(22) but with regards to asphyxia, the literature documents conflicting views(23-25). In the present study, a higher proportion of asphyxiated children were found to have "soft" neurological signs as compared to controls.

Although asphyxia per se is recognized as a significant perinatal risk

factor, the interaction between asphyxia and adverse environmental factors has not been well established. Sameroff and Chandler(26) emphasize that a combination of perinatal risk factors and non-optimal rearing conditions can lead to poor developmental outcome whereas good rearing conditions can ameliorate the risk. In the present study, similarity in socio-economic and maternal education characteristics precluded an anlaysis

of the influence

of

rearing conditions on developmental

outcome amongst the asphyxiated and control children.

In conclusion, although the asphyxiated

children performed in the normal range in various tests, in comparison to the control group they were clearly disadvantaged on nearly every measure tested. These

children therefore tend to have a poor school performance and learning difficulties, for which they need to be referred for Special education. With a little extra help,

early detection and modification of the home environment, these children

can continue in normal schools and achieve better grades.

TABLE

III

Results of Psychometric Tests

|

Variables

|

Group 1

|

Group 2 |

Asphyxia

(n

=

27) |

Control

(n

=

28) |

Asphyxia,

(n

=

27) |

Control

(n

=

29) |

|

Tests of Cognition

|

|

.

Stanford Binet IQ

|

106.7**

|

116.3 |

103.3* |

110.6 |

|

|

(13.8) |

(11.6) |

(12.5) |

(7.3) |

|

.

Progressive matrices

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

IQ

|

105.6**

|

116.6 |

102.3** |

111.8 |

|

|

(14.0) |

(10.8) |

(12.7) |

(10.3) |

|

- < 25th centile |

5 (18.5%)* |

0 |

8 (30.0%)* |

1 (3.4%) |

|

Tests

of Motor Function

|

|

.

Soft Signs

|

11(41%)*

|

3 (11%) |

6 (22%)* |

1 (3.4%) |

|

-

RR (95% CI)

|

2.01 |

|

2.0 |

|

|

|

(1.2, < 3.2) |

|

(1.2, < 3.1) |

|

|

.

Bender Gestaft

|

9 (33%)

|

3 (10%) |

13 (48%) |

6 (21%) |

|

-

RR (95% CI)

|

1.79 |

|

1.81 |

|

|

|

(1.1, < 2.9) |

|

(1.08, < 3.0) |

|

|

Social Maturity

|

|

|

|

|

|

.

Vineland Scale SQ

|

106.6**

|

117.7 |

103.6** |

111.7 |

|

|

(13.4) |

(9.4) |

(14.0) |

(8.5) |

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.005; Values depict either Mean (SO), Number (%) or RR (95% CI).

TABLE IV

Results of Tests of Academic Achievement

|

Variables |

Group 1

|

Group 2 |

Asphyxia

(n

=

24) |

Control

(n

=

25) |

Asphyxia

(n

=

24) |

Control

(n

=

25) |

|

. WRAT -R

|

|

- Reading

|

106.3*

|

118.6 |

103.4* |

112.7 |

|

|

(17.7) |

(10.7) |

(12.2) |

(9.6) |

|

- Spelling |

107.1 ** |

119.2 |

102.5** |

112.0 |

|

|

(17.5) |

(11.1) |

(11.9) |

(9.3) |

|

- Maths |

117.2* |

126.2 |

106.1 * |

116.7 |

|

|

(19.4) |

(10.8) |

(15.1) |

(12.5) |

*

p < 0.05; ** p< 0.005; Values depict Mean (SD).

|

1.

Apgar V. A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Curr Res Anesth Analg 1953; 32: 260-267.

2. Drage JS, Kennedy C, Berendes H, Schwartz BK, Weiss W. The Apgar score as an index of infant morbidity. Dev Med Child Neurology 1966; 8: 141-148.

3.

Dweck HS, Higgins W, Dorman LP, Saxon SA, Benton JW, Cassidy G. Developmental sequelae in infants having suffered severe perinatal asphyxia. Am

J Obstet Gynecol 1974; 119: 811-815.

4.

Richards FM, Richards lOG, Roberts CJ. The influence of low Apgar rating on infant mortality and development. Clin Dev Med 1968; 27: 84-88.

5.

Levene MI, Corindulus H. Comparison of

two

methods of predicting outcome in perinatal asphyxia. Lancet 1986; 1: 67-69.

6.

Robertson CMT, Finer NN, Grace MGA. School performance of survivors of neonatal encephalopathy associated with birth asphyxia at term.

J

Pediatrics 1989; 114: 753-760.

7.

Kulshreshta SK. Hindi Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale. Hindi Adaption of Third Revision Form L. Allahabad, Manav Sewa Prakashan, 1971.

8. Raven J. Guide to Using the Colored Progressive Matrices. London, H.K. Lewis, 1974.

9.

Jastak S, Wilkinson G. Wide Range Achievement Test Revised (WRAT-R) Wilmington Del, Jastak

Association, 1984.

10. Bender L. Instructions for the Use of Visual Motor Gestalt Test. New York, American Ortho Psychiatric Association, 1946.

11.

Koppitz EM. The Bender Gestalt Test for

Young Children, New York, Grune and Stratton, 1963.

12.

Hertzig ME. Neurologic evaluation schedule. In: Soft Neurological Signs, 1st edn. Eds. Tupper DE, Johnson R. New York, Grune and Stratton, 1987; pp 355- 358.

13.

Malin Rev Fr Dr. A.J. Vineland Social Maturity Scale and Manual. Indian Adaption. Ed. Bharata J. Mysore, Swayam Sidha Prakashan, 1992.

14.

Robertson CMT, Finer NN. Educational readiness of survivors of neonatal

encephalopathy associated with birth asphyxia at term.

J

Dev Beh Pediatrics 1989;

9: 298-307.

15.

Robertson CMT, Finer NN. Long term follow up of term neonates with perinatal asphyxia. Clin Perinatol1993; 20: 483-500.

16. Corah NL, Anthoney EJ, Parker P. Effects of Perinatal Asphyxia After 7 years. Psychological Monograph-General and Applied 79(3) (include No. 596). Washington DC, American Psychological Association, 1965; p 1.

17. Scot H. Outcome of very severe birth asphyxia. Atm Dis Child 1976; 51: 712-716.

18. Thomson AJ, Searle M, Russell G. Quality of survival after severe birth asphyxia. Arch Dis Child 1977; 52: 620-626.

19.

Seidman DS, Paz I, Laor A, Gale R, Stevenson. DK, Danon YL. Apgar scores and cognitive performance at 17 years of age. Obstet Gynecol1991; 77: 875-878.

20.

Painter MJ, Scott M, Hirsch R. Fetal heart rate problems during labor: Netirologic and cognitive development at six to nine

years of age. Am

J

Obstet Gynecol 1988;

159: 854-859.

21.

Sarnat HB, Sarnat MS. Neonatal encephalopathy following fetal distress - A

Clinical and electroencephalographic study. Arch Neurology 1976; 33; 696-705.

22.

Hertzig ME. Neurological "soft" signs in low birth weight children. Dev Med Child Neuro11981; 23:778-791.

23.

Aamoudse JG, Jspeert - Gerards J, Huisjes HJ, Touwen BCL. Neurological follow-up of infants with severe acidemia. Society for Gynecologic Investigation. 32rd Annual Meeting, March 20-23, 1985 Phoenix Arizona, (Abstract No. 297), 1985.

24.

Finer NN, Robertson CMT. Richard ET, Pinell LE, Peters KL. Hypoxicischemic encephalopathy in term neonates: Perinatal factors and outcome.

J

Pediatr 1981; 98: 112-117.

25.

Low SA, Galbraith RS, Muir DW, Killen HL, Pates EA, Karchmar, EJ. Intrapartum fetal hypoxia: A study of long term morbidity. Am

J

Obstet Gynecol 1983; 145: 129-134.

26.

Sameroff AJ, Chandler MT. Reproductive risk and the continum of care taking

casualty. In: Review of Child Developmental Research, Vol. 4. Eds. Horowitz FD, Hetherington M, Scarr-Salapaters, Siegel G. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1975; pp 187-244.

|