|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58: 25-28 |

|

Suctioning First or Drying First During

Delivery Room Resuscitation: A Randomized Controlled Trial

|

|

Ashok Kumar, 1

Ravi Prakash Yadav,1

Sriparna Basu1

and TB Singh2

From 1Neonatal Unit, Department of Pediatrics

and 2Biostatistics Unit, Institute of Medical

Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, UP, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Ashok Kumar, Department of

Pediatrics, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu

University,

Varanasi 221005, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: July 23, 2019;

Initial review: November 05, 2019;

Accepted: July 13, 2020.

Clinical Trial Registration: CTRI/2017/04/008340

|

|

Objective: To compare

the effect of suctioning first or drying first on the composite

outcome of hypothermia or respiratory distress in depressed

newborns requiring delivery room resuscitation.

Design: Open-label,

randomized, parallel-group, controlled trial.

Setting: Delivery

room and neonatal intensive care unit of a tertiary-care

teaching hospital.

Patients: Depressed

newborns (n=154) requiring initial steps of resuscitation

at birth.

Intervention: During

delivery room resuscitation eligible new-borns were randomly

allocated to receive either suctioning first or drying first (77

newborns in each group).

Main outcome measure:

Composite incidence of hypothermia at admission or respiratory

distress at 6 hours of age.

Results: Both groups

were comparable with regard to maternal and neonatal

characteristics. Composite outcome was similar in both the

groups [46 (59.7%) vs 55 (71.4%)] in suctioning first and

drying first, respectively [RR (95% CI), 0.84 (0.66–1.05); P=0.13].

Incidence of hypothermia, respiratory distress at admission and

oxygen saturation at 6 hours were also similar. On admission to

NICU, hypothermia was observed in 26 (33.8%) neonates in

suctioning first group and 33 (42.8%) neonates in drying first

group but by one hour of age the proportion of hypothermic

neonates was 13 (16.9%) and 14 (18.1%), respectively.

Conclusion: In

newborns depressed at birth, the sequence of performing

initial steps, whether suctioning first or drying first, had

comparable effect on composite outcome of hypothermia at

admission or respiratory distress at 6 hours of age.

Key words: Hypothermia, Initial

steps, Mortality, Newborn, Outcome, Respiratory distress.

|

A pproximately 10%

of newborns require some assistance to initiate and sustain

effective breathing at birth [1], and perinatal asphyxia

accounts for 23% of 4 million neonatal deaths each year

globally [2]. Skilled delivery room resuscitation can

prevent many of these deaths and neurodevelopmental

handicaps in survivors.

All depressed newborns requiring delivery

room resuscitation should receive ‘initial steps’ before

initiating positive pressure ventilation. These essentially

constitute temperature maintenance, positioning, suction-

ing, drying and tactile stimulation. Suctioning is done to

clear the airway and drying is done to prevent heat loss.

Though the sequence of suctioning followed by drying has

been endorsed as the part of initial steps in neonatal

resuscitation program (NRP) of the American Academy of

Pediatrics (AAP) [3], it is based on expert opinion rather

than evidence. It is not clear whether the same sequence

should be followed in a resource-limited settings of lower

and middle income countries, where the danger of hypothermia

constitutes a bigger threat [4-6]. Due to this dilemma, the

Indian NRP (first edition) [7], advocated for the sequence

of drying followed by suctioning as initial steps in Indian

scenario. However, in neonatal resuscitation module of

Facility-based newborn care [8], the sequence has been

changed to suctioning first, followed by drying.

Contradictory recommendations have led to confusion among

health professionals, with variations in practice and

training. The objective of the present study was to compare

the effect of suctioning versus drying as a first procedure

during delivery room resuscitation on the composite outcome

of hypothermia at admission or respiratory distress at 6

hours of age.

METHODS

This open-label, randomized controlled

trial was conducted in the delivery room and neonatal

intensive care unit (NICU) of a tertiary care teaching

hospital of central India from March, 2016 to August, 2017.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics

Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from the

parents before delivery. The cases was excluded, if there

was insufficient time to obtain informed consent.

Consecutively delivered inborn neonates

who were depressed at birth and required initial steps of

resuscitation were included. Depression at birth was defined

as presence of apnea or gasping and/or limp or poor muscle

tone. Neonates delivered through meconium stained liquor,

major congenital anomalies and cases where there was

insufficient time to obtain consent were excluded. Antenatal

details of the mothers including maternal age, gravida,

parity, receipt of antenatal care, complications of

pregnancy, evidence of fatal distress, mode of delivery, and

relevant investigations done in the pregnant mother,

including ultrasonography were noted.

Eligible newborns were randomized into

one of two groups (suctioning first or drying first) using

random permuted blocks of 4, 6 or 8. The randomization

sequence was prepared by an independent person not involved

in the conduct of study. Allocation of newborns to different

groups was done using serially numbered, opaque and sealed

envelopes.

All deliveries were attended by two

pediatric residents who were trained in neonatal

resuscitation as per AAP guidelines. After delivery, if a

newborn was found to be apneic or limp, the umbilical cord

was clamped immediately and baby was placed under radiant

warmer with neck slightly extended. By this time, one member

of the team or a staff nurse opened the sealed envelope and

further sequence of initial steps was performed as per

randomization. During resuscitation, oxygen saturation was

recorded from right hand or wrist, using hand-held Masimo

pulse oximeter. For suctioning, wall mounted suction was

used with a pressure not exceeding 100 mm of Hg. Each

attempt at suctioning was limited to no more than 3 to 5

seconds, and care was taken to avoid vigorous or deep

suctioning. We used a pre-warmed towel to dry the baby and

removed wet towel to prevent further heat loss. After

completing initial steps including tactile stimulation, if

the baby continued to have apnea/gasping breathing or

bradycardia (heart rate 100/minute), positive pressure

ventilation was initiated. The remaining steps of

resuscitation were similar in the two groups.

All neonates were admitted to NICU and

were monitored and managed as per unit protocol. Babies were

kept under radiant warmer with temperature set at 36.5 oC.

Babies were monitored using a predesigned proforma for heart

rate, oxygen saturation, temperature, capillary refill time,

respiratory rate, and other signs of respiratory distress

(chest wall retractions, grunting and bilateral air entry

into the chest). Investigations included blood glucose,

serum electrolytes, chest X-ray, sepsis workup (complete

blood count, absolute neutrophil count, C-reactive protein

and blood culture), if needed, arterial blood gas analysis

and renal function tests. Other tests included

echocardiography and cranial ultrasonography, as and when

necessary. Respiratory support was given via oxygen hood,

continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), high flow nasal

cannula (HFNC) or mechanical ventilation as per need.

Intravenous fluids, parenteral nutrition, and feeding were

provided. Complications were managed as per our unit

protocol.

Primary outcome variable was composite

outcome of admission hypothermia or respiratory distress at

6 hours of age. Hypothermia was defined as rectal

temperature <36.5oC.

Rectal temperature was recorded using a low-reading rectal

thermometer. Respiratory distress was defined as presence of

at least one of the following: respiratory rate >60/minute,

chest wall retractions and grunting. Secondary outcome

variables included the need and duration of positive

pressure ventilation, chest compressions and medication use

during delivery room resuscitation, oxygen saturations

during first 10 minutes of age, incidence of hypothermia and

respiratory distress within 24 hours, development of

complications and duration of hospital stay and outcome.

Assuming an expected incidence of the

need for delivery room resuscitation of 10% [3], a precision

(d) of 0.05 and level of confidence of 95%, the sample size

calculated was 138. Considering 10 % attrition rate, the

total sample size was 154 newborns, 77 in each group

(www.kck.usm.my/ppsg/statistical_resources/SSCPS

version1001.xls).

Statistical analyses: The

statistical program SPSS version 16.0 was used for analysis.

Independent samples t test/Mann Whitney U test and Fisher

exact test were used as applicable to compare parametric and

non-parametric variables. Risk ratios (RR) with 95% CI were

calculated for outcome variables. The data were analyzed on

intention to treat basis. A P value of <0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

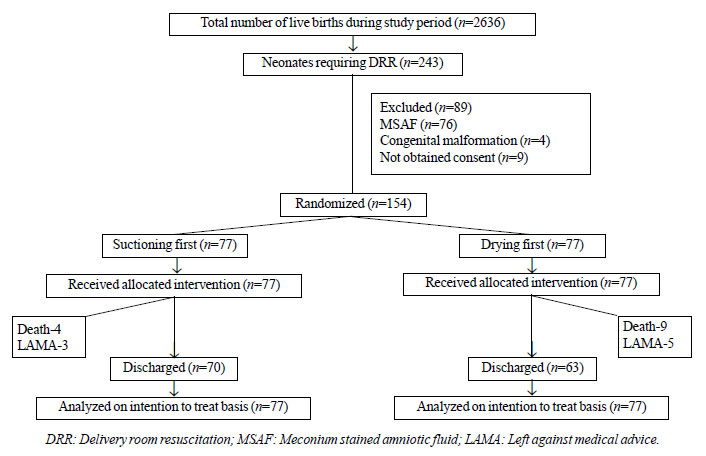

Each group included 77 neonates, and all

neonates received their allocated intervention (Fig.

1). Both the groups were similar with respect to

maternal and neonatal characteristics, except the incidence

of eclampsia, which was significantly higher in suctioning

first group (Table I).

|

|

Fig.1 Flow of

participants in the study.

|

Table I Maternal and Neonatal Characteristics of Study Participants

|

Suctioning first

|

Drying first

|

|

(n=77) |

(n=77) |

|

Maternal characteristics |

|

|

|

*Maternal age, y |

26.2 (4.5) |

25.9 (4.1) |

|

#Gravida |

2 (1 -3) |

2 (1 -3) |

|

PIH/ Pre-eclampsia |

7 (9) |

6 (7.7) |

|

Eclampsia |

21(27.2) |

10 (12.9) |

|

Antepartum hemorrhage |

4 (5.1) |

5 (6.4) |

|

PV leak >18 h |

11 (14.2) |

16 (20.7) |

|

Maternal fever |

2 (2.6) |

2 (2.6) |

|

Fetal distress |

10 (12.9) |

15 (19.4) |

|

Cesarean section |

56 (72.8) |

53 (68.9) |

|

Neonatal characteristics |

|

|

|

*Gestation, wk |

35.4 (3.5) |

34.7 (3.1) |

|

*Birthweight,

g |

2123 (67) |

2131 (64) |

|

Male gender |

43 (55.8) |

46 (59.7) |

|

#APGAR score |

|

|

|

1 min |

4 (3-5) |

4 (3-6) |

|

5 min |

7 (6-8) |

8 (7-9) |

|

Values in no. (%) except*mean (SD) or #median

(IQR); PIH: Pregnancy induced hypertension; PV: Per

vaginal; P>0.05 for all variables between the two

groups. |

The composite outcome of hypothermia at

admission or respiratory distress at 6 hours of age was

similar in suctioning first and drying first, respectively

[46 (59.7%) vs. 55 (71.4%); RR (95% CI), 0.84 (0.66-1.05);

P = 0.13] (Table II). Among the secondary

outcome variables, oxygen saturation within 10 minutes after

birth, incidence of hypothermia at admission, and

respiratory distress at different time intervals during

first 6 hours of age were also similar (P>0.05) (Table

II). On admission to NICU, 26 (33.8%) neonates in

suctioning first group and 33 (42.8%) neonates in drying

first group experienced hypothermia (Table II).

By one hour of age hypothermia was observed in 13 (16.9%)

and 14(18.1%) neonates, respectively. The differences were

not significant.

Table II Outcome Variables in Neonates in the Two Study Groups

|

Variable |

Suctioning first (n =77) |

Drying first (n=77) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

|

Composite outcome, n (%) |

46 (59.7) |

55 (71.4) |

0.84 (0.66-1.05) |

|

Hypothermia at admission |

26 (33.8) |

33 (42.8) |

0.79 (0.52-1.18) |

|

Respiratory distress at 6 h |

34 (44.2) |

38 (49.4) |

0.89 (0.64-1.25) |

|

Oxygen saturation (%)a |

|

|

|

|

At 1 min |

60 (56-63) |

59 (54-63) |

- |

|

At 2 min |

68 (64-72) |

68 (64-72) |

- |

|

At 5 min |

84 (82-87) |

84 (81-86) |

- |

|

At 10 min |

94 (92-95) |

93 (92-95) |

- |

|

Bag and mask ventilation |

73 (94.8) |

75 (97.4) |

0.97 (0.91-1.04) |

|

Duration, sa |

30 (30-30) |

30 (30-60) |

- |

|

Bag and tube ventilation |

50 (64.9) |

43 (55.8) |

1.16 (0.89-1.50) |

|

Duration, mina |

5 (5-10) |

5 (1-10) |

- |

|

Chest compressions

|

0 |

4 (5.1) |

0.11 (0.01-2.03) |

|

Adrenaline usage |

0 |

2 (2.5) |

0.20 (0.01-4.10) |

|

Death |

4 (5.2) |

9 (11.7) |

0.44 (0.14-1.38) |

|

All values in no (%) except amedian (IQR); RR:

Relative risk; Composite outcome - hypothermia at

admission or respiratory distress at 6h of age;

P>0.05 for all variables between the two groups. |

Resuscitation details for both the groups

are summarized in Table II. No significant

difference was observed in the extent of delivery room

resuscitation received by both the groups. Four (5.2%)

neonates expired in the suctioning first group, whereas 9

(11.7%) expired in the drying first group (P>0.05) (Table

II).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that

suctioning first or drying first during initial steps of

delivery room resuscitation result in comparable rates of

composite outcome of hypothermia at NICU admission or

respiratory distress at 6 hours of age in depressed

newborns. We could not find any study in literature which

investigated the comparative efficacy of drying versus

suctioning as a first intervention during delivery room

resuscitation.

The incidence of hypothermia was quite

high in our study cohort, as compared to previous data from

India [9-11]. Although newborns were resuscitated under

radiant warmer, they were transported to NICU without any

additional source of heat, which might have led to higher

incidence of admission hypothermia in our study population.

Preponderance of preterm newborns in study population might

have added to the burden of hypo-thermia in study cohort. We

did not measure the temperature of newborns in delivery

room before transporting them to NICU. The possibility that

some babies developed hypothermia during resuscitation

cannot be excluded. It is well known that hypothermia at

admission is associated with poor outcome [4-6]. We did not

use polyethylene wraps to maintain temperature of extremely

preterm newborns at birth, which obviates the need for

drying in these cases, as drying was applied as one of the

comparator interventions in the present study.

We observed no difference in the extent

and duration of resuscitative interventions between the two

groups. The mortality rates were also comparable in the two

groups.

To conclude, it makes little difference

to the outcome whether newborns are suctioned first or dried

first and either approach is acceptable. However, to bring

uniformity and consistency among health professionals and

to avoid confusion in the implementation of NRP guidelines,

we should follow an approach which is in agreement with

standard guidelines unless there is a definite evidence of

preferring one approach over the other.

Contributors: AK, SB: conceptualized

and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data

collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and

revised the manuscript; RPY: designed the data collection

instruments, collected data, carried out the initial

analyses, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; TBS:

analyzed the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and

agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical clearance:

Institutional Ethics Committee of Institute of Medical

Sciences, BHU; No. Dean/2014-15/EC/1455 dated 17 October,

2015.

Funding: None; Competing interests:

None stated.

|

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN?

•

During delivery room

resuscitation, the sequence of performing suctioning

and drying is based on expert opinion rather than

any evidence.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

•

Suctioning first or drying first during delivery

room resuscitation has comparable effect on the

composite outcome of admission hypothermia or

respiratory distress at 6 hours of age in newborn

infants.

|

REFERENCES

1. Barber CA, Wyckoff MH. Use and

efficacy of endotracheal versus intravenous epinephrine

during neonatal cardiopul-monary resuscitation in the

delivery room. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1028-34.

2. Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, et

al; Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and

UNICEF. Global, regional, and national causes of child

mortality in 2008: A systematic analysis.

Lancet. 2010;375:1969-87.

3. Wyckoff MH, Aziz K, Escobedo MB, et

al. Part 13: neonatal resuscitation: 2015 American Heart

Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation.2015;132:

S543-60.

4. Sodemann M, Nielsen J, Veirum J,

Jakobsen MS, Biai S, Aaby P. Hypothermia of newborns is

associated with excess mortality in the first 2 months of

life in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Trop Med Int Health.

2008;13:980-6.

5. Miller SS, Lee HC, Gould JB.

Hypothermia in very low birth weight infants: Distribution,

risk factors and outcomes. J Perinatol. 2011;31:S49-56.

6. Mullany LC, Katz J, Khatry SK, LeClerq

SC, Darmstadt GL, Tielsch JM. Risk of mortality associated

with neonatal hypothermia in southern Nepal. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med. 2010;164:650-6.

7. Neonatal Resuscitation: India. 1st ed.

National Neonato-logy Forum of India; 2013.p.5.

8. Neonatal Resuscitation Module.

Facility Based Newborn Care: Ministry of Health and Family

Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi;2014. p.9-16.

9. Kumar R, Aggarwal AK. Body

temperatures of home deli-vered newborns in north India.

Trop Doct. 1998; 28: 134-6

10. Kaushik SL, Grover N, Parmar VR,

Kaushik R, Gupta AK. Hypothermia in newborns at Shimla.

Indian Pediatr. 1998; 35: 652-6.

11. Bang AT, Reddy HM, Deshmukh MD, Baitule SB, Bang RA.

Neonatal and infant mortality in the ten years (1993 to

2003) of the Gadchiroli field trial: effect of home-based

neonatal care. J Perinatol. 2005; 25(Suppl 1): S92-107.

|

|

|

|

|