Dr. S joined postgraduate residency in Pediatrics

just a few months ago. Soon, the head of the department started

receiving complaints regarding him from staff nurses, fellow residents,

and patient attendants. He was reported to be rude and aggressive while

dealing with children and their parents. He often argued and quarrelled

with staff nurses and other subordinates during the work hours. He used

to ignore the instructions given by his seniors. However, he behaved

extremely well in front of the faculty members; it was difficult for the

faculty to believe that he has a problem!

Medical teachers often face situations where students

or trainees are problematic or challenging. All clinical teachers want

their team members to be competent, compassionate, cooperative and

constructive. Medical Council of India (MCI) describes the role of

Indian medical graduates beyond being a clinician, to be a leader,

professional, communicator, and a lifelong learner who is ethical and

committed to excellence [1,2]. Qualities of a ‘great resident’ or a

‘high performing resident’ include being trustworthy, hardworking,

efficient, and self-directed learner [3]. It is, however, not unusual to

encounter trainees with a deficit in knowledge, lack of clinical

judgment, annoying behavior, inappropriate interaction with colleagues,

or being late or absent. All these serve as significant obstacles in the

attainment of the desired competencies [4-8].

Problem behavior of one resident sometimes spoils the

reputation of the entire department and hampers training of fellow

residents. Such a resident often diverts the time and energy of other

fellow residents and faculty members. Improper handling may result in

violent behavior to self or others. It is thus essential to recognize

the problem resident, and institution of remedial measures at earliest.

Definition

Myriads of terms are used for a problem resident:

troublemaker resident, problem learner, difficult resident, the

burned-out resident, disruptive resident, and so on [6-8]. A ‘problem

learner’ has been defined as one whose academic performance is

significantly below performance potential because of a specific

affective, cognitive, structural, or interpersonal difficulty [8].

American Board of Internal Medicine defines problem resident "as a

trainee who demonstrates a significant enough problem that requires

intervention by someone of authority, usually the program director or

chief resident." In simple terms, a problem resident is the one who does

not meet the expectations of the training program owing to the deficit

in knowledge, skill or attitude.

Statement of the Problem

In a study by Reame, et al. [5], the

prevalence of ’resident in trouble’ was estimated to be 9.1%. They

observed psychiatric illness, substance abuse, attitudinal problems,

interpersonal conflicts and insufficient knowledge to be the common

reasons. In another internal medicine residency program, the prevalence

of problem resident was estimated to be 6.9%. The most common

attributable causes included insufficient medical knowledge, poor

clinical judgment, and inefficient use of time [4]. In a nationwide

survey of psychiatry residency program in the United States, it was

observed that 3.3% of residents were terminated in a four-year period

for unacceptable performance [9]. Data from India on this issue are

lacking.

Predisposing Factors

Knowledge Deficit

One of the most common attributable cause of problem

resident is insufficient knowledge [5]. The resident may have poor

baseline subject knowledge or is slow to grasp the basic concepts

leading to an unsatisfactory performance at work (Box I).

The regular internal assessment might detect academic deficiency and

provides an opportunity to rectify the deficit. Lack of organizational

skills and ineffective time management are some of the other hurdles in

acquiring the requisite knowledge.

|

Box 1 Hunt’s Classification of Problem

Learner

Type I (frequent* and

difficult#)

• Bright with poor

interpersonal skill

• Excessively shy,

non-assertive

Type II (frequent* and not

difficult#)

• Poor integration skills

• Overeager

• Cannot focus on important

issue

• Disorganized

• Disinterested

• Poor knowledge

Type III (not frequent* and

difficult#)

• Cannot be trusted

• Psychiatric problem

• Substance abuse problem

• Manipulative

Type IV (not

frequent* and not difficult#)

• Too causal or informal

• Avoids works

• Intellectually inferior

• Avoids patient contact

• Does not show up

• Challenges everything

• Awkward

*How frequently do we

encounter this problem;

#How difficult is the problem to handle.

|

Skill Deficit

Skills required from clinical residents include the

art of history taking, correct method of clinical examination,

interpreting the clinical findings to reach a diagnosis, plan

investigation and managing the patients. One of the most essential

skills is communication of the plan to relatives and ability to discuss

the idea with colleagues and taking constructive criticism.

Communication difficulties, especially of those who travel from other

states to pursue their higher education, might have trouble

communicating in the local language. Majority of residents face problem

in skills during the first few months of residency that tends to improve

with time. Surgical hands-on skills often need constant supervision. The

persistent deficit of skill development despite repeated reinforcement

leads to a problem.

Attitude or Personal Problems

Attitude or personality problems stem from a deficit

in motivation. The problem resident often has a poor interpersonal

relationship and is not dependable for independent patient care (Box

2). Residents with attitude problems are the most difficult ones to

handle.

|

Box 2: Case Scenarios of Fictitious

Problem Residents

Fictitious Dr. Y

• She is very hard working, comes early to

wards, leaves very late.

• Unfortunately scores poor on assessment.

She takes many hours to analyze a patient’s history and still

does not make any sensible plan for individual patients.

• She does not understand the instructions of

seniors at one go. They need to repeat it multiple times.

• She often writes wrong doses of drugs or

sends false samples of a patient.

• She is never able to understand the

rationale behind the choice of investigation and management.

• Owing to this, She is considered

disorganized at work and faculty prefers not to assign any vital

work to him.

Fictitious Dr. K

• He often reports late to his duty or may be

absent without any prior information, and he usually keeps his

mobile phone switched off.

• There are frequent complaints from other

supportive staff regarding his rude behavior with patients and

his colleagues.

• He tends to fight, use abusive language,

and gets into confrontation mode when into an argument.

• He is often lazy, avoids works, gives lame

excuses and tends to blame others for his non-performance.

• He passes on his share of work to next

relieving resident.

• He is often spotted chatting over his

mobile phone during the working hours. He shows little interest

during the clinical rounds and is often seen wandering away from

the wards during his duty hours.

|

Problems pertaining to residents

Personal problems like bereavement from loss of loved

ones, struggle in the family, or difficulties in personal relations may

affect the performance of residents. Poor interpersonal relationships

lead to prejudiced work atmosphere and impair learning. Psychiatric

illness and substance abuse among residents needs early identification

and correction. These problems often result in stress, depression, low

self-esteem, and fear of failure.

Many students choose a medical or surgical specialty

based on their score rather than their interest. Such discordance may

result in a problem during the early days of residency. Few residents

have adjustment issues considering the latency of 2-3 years after

completion of medical school before they get into a specialty. In a

study by Hunt, et al. [10], it was observed that most common

problem learners were those with cognitive issues and poor interpersonal

relationship.

Problems pertaining to teachers

Faculty members with unrealistic expectations,

stressful personal life, or working in an unsatisfactory workplace often

vent out their anger and frustrations at the resident. The behavior may

initiate or exacerbate problems in the resident. An excellent role model

faculty produces better professional behavior among residents [11,12]. A

problematic faculty; however, is more likely to produce a problem

resident.

The teacher is often assigned the dual role of

clinician and teacher, and a few fail to live up to the expectations.

Few teachers may become oblivious to the problem resident altogether so

as to avoid direct confrontation and few may vent out their anger by

scolding the resident. On the other hand, few faculty members suddenly

become soft, primarily to avoid any possible personal litigations.

Often, faculty members are reluctant to provide an honest assessment of

the residents, and mark them as satisfactory despite being problematic

[13]. This only aggravates the situation.

Problems pertaining to system

Workplace learning varies widely between different

institutions, depending on opportunity, motivation, and capabilities

[14]. In government facilities, barriers to effective workplace learning

might include deficient infrastructure, deficient manpower, and

unmanageable patient load [15]. In addition, lack of access to peer,

lack of management support, lack of access to technology, lack of

funding, and unsupportive staff attitude are other barriers to workplace

learning [14]. Certain institutions despite having excellent

infrastructures may lack expertise and teaching exposure required during

residency training [16]. Many students migrate from one state to another

state for pursuing postgraduate residency. Relocation to a new

institution often invites financial concerns, isolation, and social

problems leading to resident stress and adjustment issues [17]. All

these factors may contribute to the making of a problem resident.

Unprofessional Behavior

Some of the professional etiquettes expected from

residents include being courteous to your colleagues and seniors, being

on time to work, wearing appropriate clothes to the hospital, showing

appropriate gestures while speaking to patients, and most importantly to

keep one’s grudges and egos away while dealing in a professional

atmosphere. Unprofessional blogs and social media posts such as binge

drinking, posting sexually appealing photos, sharing patient videos on

social media, posting raw or confidential data of institute, and

personal comments on faculty members or peer colleagues are some of the

commonly encountered problems [18,19]. Fabricating patient reports to

meet preoperative criteria, and verbal or physical abuse of junior

doctors are some of the extreme behaviors encountered among few

residents [20]. There is rising intolerance about relations of doctors

with pharmaceutical companies or private laboratories for some financial

or other favorable incentives [21].

Addressing A Problem Resident

The first step in the evaluation of a problem

resident is to be sure about the diagnosis [7]. A single adverse

incident, personal grudges, and overheard conversation may end up in

wrongly labelling a resident as a problem resident. Residents obviously

do not like to be outcasted as a problem resident [22]. It affects their

relations with peers, patients and teachers. A resident erroneously

blamed for any wrong happenings results in denial, anger and loss of

self-confidence [6].

Sharing all concerns over a faculty meeting is

essential [23]. A group consensus on a resident being a problem resident

is necessary before proceeding to determine the problem and its remedial

measure. Once the problem is identified, it would be useful to determine

how frequently do we encounter this problem, how difficult is it to

handle this problem, and how much is it affecting the ongoing learning

of the student and his/her peers [10]. For example, a resident who is

frequently absent from his duties owing to excessive alcohol abuse is

not a frequent but quite a difficult problem to handle. Likewise, a

disorganized first year with poor knowledge base is quite a common

problem, but it improves with interventions (Box 2).

Talk to the resident

The resident should be called for a meeting with the

program director who should list the concerns without criticizing or

discriminating the resident [23]. Perception of the problem by resident

and its possible remedial measures that he/she perceives should be

considered. Enquire about personal problems of the resident, including

those from family.

Talk to colleagues

Feedback from other supportive staff including peers,

nurses, support staff, and patient attendants might help [12]. It is

essential to identify the occurrence and frequency of problem and

situations where such a problem emerges. History of drug or alcohol

abuse needs to be ascertained from the peers [24]. Inter-resident

scoring cards are used to assess a resident as perceived by their peers

in an objective manner.

Designing remedial measures

Fictitious Dr. Y was disorganized and had a gross

deficit in knowledge and skills (Box 2). Owing to repeated

complaints from casualty team members, she was rotated to the general

pediatric ward. She was tagged to a mentor faculty and chief resident

who would intensely monitor his progress. They would conduct one to one

tutorial, assign her the additional reading task with fixed timelines,

and supervise her examination skills at the bedside. Her analytical

skills were sharpened by use of simple methods like one-minute preceptor

model [25]. Considering the hard-working nature of Dr. Y, she had an

excellent performance at the end of 3 months and then was rotated back

to the casualty team. She was tagged to a senior shadow peer for next

two months before she was assigned independent duties.

Fictitious Dr K had a major problem in attitude that

led to a negative and unprofessional workplace environment (Box

2). He was called for a meeting with the program director and all

faculty members. Problems encountered were enlisted, and justification

for the same was sought. A verbal warning was given, failing which a

written memorandum was issued. His parents were informed of the minutes

of the meeting. His responsibilities during clinical postings were

delineated, and he was not allowed to switch on his mobile phone during

work hours. His interactions with patients, peers and nurses were video

recorded. He became conscious of his actions being recorded. These video

records were reviewed in a subsequent meeting with the resident, and

corrective measures were suggested to him. A timeline was provided for

correction of his actions, failing which he was warned of possible

termination of his candidature for the program. He was tagged to a role

model teacher and peer with whom he worked for next three months. His

behavior improved dramatically. He was more polite, respectful and

considerate in his actions at the workplace. He would finish all his

work before leaving the ward.

Teaching medical professionalism is challenging, but

essential part of medical training. One of the most effective ways to

teach professionalism to residents is to foster faculty role modeling

[23]. Residents often look up to a positive role model to imitate

his/her professionalism. Majority of problem residents improve with

appropriate and timely remedial measures. Remedial measures must define

the deficiency, provide a pathway for its rectification, set minimal

benchmark goals or expectations in an acceptable timeline, and

evaluation based on set goals [13].

Broad identification of problem into cognitive,

behavioral or a combination of both is essential to design specific

cures. Majority of attitudinal problems require extensive close

monitoring and feedback, and, in some situations, require psychological

help. The structured reading session can be planned for those with the

poor knowledge base (Table I). The Problem Resident needs

to be involved in identifying the problems and designing their remedies,

based on his/her priorities.

Table I Remedial Measures for Problem Residents

|

Deficit domain |

Remedial measures |

|

Knowledge deficit |

One to one mentorship, faculty tutorials, creating reading

assignments with the timeline, peer support, increased frequency

of formal meeting with program director during the first year of

residency, regular reassessment, increased faculty advisor

meetings, identifying the best teacher or role model who could

probably sail through the tough time. |

|

Skill deficit |

Skill training, hands-on training, peer mentorship, supervised

or tagged resident, formal mentorship program tagging them to

likeminded faculty members, increased supervision by case

discussion, review of patient management problems, faculty

mentor to periodically monitor the gain of skills. |

|

Psychiatric issues |

Psychological and psychiatric consultation, appropriate

documentation of all meetings, the involvement of family members

is essential, consultation and remedial measures in a temporary

file can be helpful; medical clearance before the resident can

be brought back to work; can extend the training period for 3-6

months till health is returned. |

|

Adjustment issues |

Time is an effective healer. Majority respond and adjust to new

environment. Peer and faculty support helps. Providing easy

rotation in the beginning, monthly off days. providing leave of

absence, home sickness resolves with time once they start

enjoying residency, bringing parents to the hostel to spend some

more time till he gets adjusted. |

|

Attitude problem |

The probationary period during the residency program would be a

useful addition to observe for behavior and attitudes. Direct

observation of good patient-doctor interaction, video recording

the session and correcting the mistakes (videotape reviews).

|

|

Unprofessional behavior |

Stringent punitive action like a warning, issue of the

memorandum, seeking a written explanation for misbehavior,

temporary suspension from the program, the involvement of legal

cell of the institution to decide a plan of action. |

|

Problems at the faculty level |

Faculty orientation workshops on dealing with Problem

Residents, increased incentives for faculty involved in

teaching, effective feedback from students. |

|

Problems at the system level |

Decreasing work hours, providing conducive workplace, setting up

problem box in each department in which residents can

confidentially give honest feedbacks, feedback to system

director regarding the work environment. |

Three golden rules for correction include "act early,

maintain confidentiality, and document everything" [7,22]. The plan

should be individualized. Set up achievable goals and devise a timeline

for each of the desired goals. It is essential to identify the red flag

signs that require psychiatric consultation, including suicidal

tendency, harm to patient, and substance- or alcohol- abuse. Finally,

ensure that a problem resident graduates out of the department sans

his/her problems.

Prevention

Can we predict at the outset that a resident will be

problem resident? Robust educational system ideally should have rigorous

screening mechanism for recruiting residents for the teaching program. A

problem resident is often recognized within the first year of residency,

or more often they come to attention when a resident has poor

performance in the ongoing assessments. Periodic assessment of residents

should ideally include core medical knowledge, interpersonal skills and

communication, practice-based learning, and professionalism [23].

Few problems come to attention following a complaint

about the resident in some adverse event like fights with colleagues or

patient or when there is gross mismanagement for any patient. Indian

system recruits medical postgraduates through common written entrance

examination that often lacks personality assessment [26]. Moreover, with

the advent of online admission sessions, while allotting postgraduate

seats, institutions have no control over the recruitment of students.

Even resident with adverse remarks on the conduct certificate during

graduation years can safely land in prestigious institutions solely

based on cognitive abilities [27]. The selection procedure for residency

should not only look for core medical knowledge, but also the past

performance during the undergraduate course, the opinion of teachers and

peers. Screening for personality traits, motivation, character,

affective domains and communication skills need to be incorporated in

the selection process [28].

Once a resident is inducted into the system, an

orientation plan should be in place. It should include orientation to

the clinical postings and their expectations from residents. Importance

of socialization should be emphasized. They should go to movies, go to

dine outside, and have regular birthday parties even at the workplace –

during the lunch hours. Mentoring a resident is an essential aspect of

medical training [29]. It shapes the personal and professional

development of the resident. Effective incorporation of mentorship

program during residency could avert emergence of problem resident.

Mentors selected by free choice have been shown to be better than

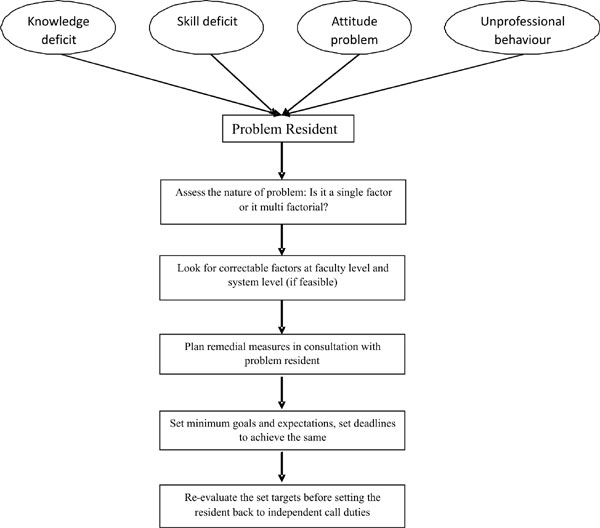

assigned mentors [30]. A broad approach to handling a problem resident

has been summarized in Fig. 1.

|

|

Fig. 1 Approach to a problem

resident.

|

Conclusion

Resident doctors face a variety of professional and

personal problems, including deficits in knowledge, skills or problems

with attitude. Faculty members and institutional heads must be

sensitized to handle these problems. Remedial measures need to be

individualized and must be framed with the involvement of affected

resident. One-to-one faculty mentorship, peer support, psychological

consultation, rotating the resident out of difficult workplace,

stringent monitoring of their behavior, and providing effective feedback

are some of the remedial measures to handle a problem resident.

Providing enjoyable learning experiences should be the goal of every

residency program.