The World Association of Perinatal Medicine defines a

fetus as viable when it is mature enough to survive into the neonatal

period with the clinical support that is available. More objectively,

Periviable birth is currently defined as delivery occurring from 20 0/7

weeks to 25 6/7 weeks of gestation [1]. The outcome of these babies

ranges from certain or near-certain mortality to likely survival with a

high chance of long-term morbidities. When delivery is anticipated near

the limit of viability, both the family and caregiver are faced with

many complex and ethically challenging decisions.

The clinical support available in India varies across

the country and even within cities. The lack of widespread accreditation

of neonatal units makes it difficult to determine the type of support

available in a given unit. Currently, the focus is increasingly on the

ethics of giving support to neonates that are born very preterm. Since

most of India receives healthcare from out-of-pocket expenses, the

debate around care of the extremely preterm neonates often attracts

unfavorable media attention.

In this article, we discuss issues on survival and

outcomes of extremely premature infants, available guidelines, and try

to provide guidance on the need to develop a process locally that can

address this issue.

Survival and Long-term Outcomes

Historically, neonatal mortality is considered an

inevitability at or before 24 weeks of gestation [2,3]. While, we do not

have any data on the outcomes of these babies from India, a review of

studies from the past few decades do reveal an increase in the rate of

survival of newborns born at 22-25weeks of gestation [4-7]. The rates of

survival to discharge increase with increasing gestational age of

periviable babies (23-27% for births at 23 weeks, 42-59% for births at

24 weeks, and 67-76% for births at 25 weeks) [4,5,7].

Data trends on long-term sequelae are the same,

showing better outcomes at higher gestations. A follow-up study of a

cohort of periviable babies in England, demonstrated a decrease in the

proportion of children at age 30 months with severe or moderate

impairment, with increasing gestational age at birth (45% at 22-23

weeks, 30% at 24 weeks, and 17% at 25 weeks of gestation) [8]. A review

by Moore, et al. [9] also established that the incidence of

moderate-to-severe neurodevelopmental impairment among survivors at 4-8

years improved with higher gestational age at birth: 43% at 22 weeks,

40% at 23 weeks, 28% at 24 weeks, and 24% at 25 weeks of gestation.

However, even though the combined rate decreased, the rate of severe

neuro-developmental impairment alone did not vary significantly with

gestational age. A study from United States discussed survival and

long-term neurologic outcomes in more than 4,000 births from 2001 to

2011 that were between 22 to 24 weeks of gestation [9]. The results

demonstrated an actual increase in rate of survival without impairment

in the study duration, whereas the rate of survival with impairment has

remained constant. However, the lack of data from Indian settings makes

us wary of drawing any such conclusions.

The Ethics of Decision-making in the Delivery Room

The ethical principles, even in preterm infants,

remain the same as applied to other areas of medicine. The guiding

principles for the neonatologist are – beneficence (doing good), non-maleficence

(doing no harm), autonomy (respecting individual preferences) and

justice.

The principle of beneficence is a major force behind

the efforts to rescue these newborns. Traditionally, medicine’s ability

to prolong life is taken as unqualified good. However, in case of these

very premature babies, it needs to be decided whether use of medical

technology is actually postponing death rather than prolonging life.

Furthermore, life may not always be preferable to death, when continuing

life means deep suffering, a common scenario for these very premature

babies. The principle of non-maleficence is then taken into account as

significant suffering must be justified by expected outcome, while

inflicting such suffering may become unjustifiable when the likelihood

of survival becomes extremely small.

The application of the principle of autonomy is

complicated, as infants have no autonomy. Both parents and physicians

have a moral right and a legal duty to make treatment decisions in the

best interests of the baby. Parents and physicians may disagree

regarding the course of action – pertaining to uncertain medical

outcomes, different values, resources, tools and outlook [10]. For

physicians, there is a greater focus on technical components, such as

outcome data, evidence-based prognostic tools, and the clinical picture,

such as the actual presentation of the baby at birth. Conversely,

parents are generally more emotionally and psychologically invested in

any decision made, lacking the technical expertise to assess complex

clinical information.

Lastly, the principle of justice implies not only

treating similar preterm babies similarly, but also effectively using

resources (distributive justice). Aggressive care of extremely premature

babies with a remote possibility of intact survival may be considered an

inappropriate allocation of resources. Add to this a public-private

co-operation health system with variation in availability of resources,

inherently leading to unfairness.

Despite, such complexities in decision-making, it

must be remembered that the decisions that are made are going to impact

the entire life of the baby and the family; and many decisions such as

stopping care are not reversible and can have long-term impact on the

mental health of the parents. Hence, having a decision-making framework

is beneficial for all stakeholders in the process.

President’s Commission, 1983

This was a landmark decision-making framework,

although not meant specifically for treatment dilemmas at the threshold

of viability, the commission proposed ethically appropriate physician

responses to parental requests for the provision or withholding of

treatment in each of three treatment categories, viz., clearly

beneficial, of uncertain benefit, or futile [11] (Table I).

TABLE I President’s Commission’ 1983 [11]

|

Physician assessment of treatment |

Parents prefer to accept treatment

|

Parents prefer to forego treatment

|

|

Clearly beneficial to the infant

|

Provide treatment

|

Provide treatment (seek legal or other review) |

|

Ambiguous or uncertain benefit to the infant

|

Provide treatment

|

Withhold/ withdraw treatment

|

|

Futile

|

Provide treatment unless provider declines to do so

|

Withhold/ withdraw treatment |

As long as this choice does not cause substantial

suffering for the child, providers should accept it. Although,

individual health care professionals who find it personally offensive to

engage in futile treatment may arrange to withdraw treatment.

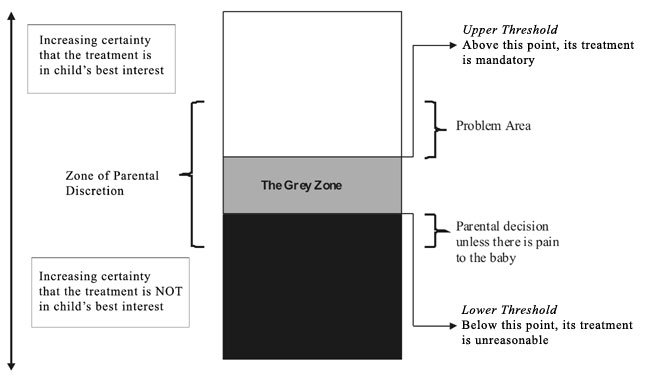

The Grey Zone and Zone of Parental Discretion

Most of the periviable babies die, while majority of

survivors have long-term morbidities. It is a difficult decision for

doctors and parent – whether you decide to treat them with the knowledge

that more often than not such efforts will be unsuccessful and result in

huge discomfort to the baby. On the other hand, not giving treatment

allows some of these babies to die who might have been saved? This is

the Grey Zone [12].

The zone of parental discretion is the ethically

protected space where parents may legitimately make decisions for their

children, even if the decisions are sub-optimal for those children [13].

|

Box 1 Guiding Principles in the Grey Zone

• Understand parents’ view on optimizing

survival or minimizing suffering beforehand during antenatal

counselling and discussion sessions.

• Keep in mind the institutional policies and

local laws.

• A stepwise approach based on newborn’s

condition and parental wishes is appropriate. Care should be

regularly re-evaluated and redirected.

• Decision for continuing care or otherwise

should be individualized – specific clinical issues, family

values/wishes, and ongoing evaluation of fetal or neonatal

condition.

• Multidisciplinary neonatal palliative care

should be provided in babies with the decision to withdraw or

withhold care.

• Healthy parent-clinician relationship with sharing of the

decision-making responsibility.

|

In the Grey Zone, the dictum is to follow parents’

wishes. The major problem area for neonatologists is when the zone of

parental discretion overlaps with area above the grey zone where

treatment is considered mandatory, but there is difference of opinion

between caregivers and parents (Fig. 1). The major guiding

principles in the Grey zone are detailed in Box 1.

|

|

Fig. 1 Conceptual framework for the

grey zone in treatment decisions.

|

Shared Decision-making

Under ordinary circumstances, parents are likely to

be the best advocates for their infants. Therefore, parental wishes

should generally be followed, and issues important to them should be

considered in decision-making. In cases of borderline viability,

clinicians may feel compelled to advocate for the neonate and provide

treatment against parental wishes. Such decisions are not ethically

justifiable if it is impossible to weigh up the potential harms to the

child or to consider what is in the best interests of the child due to a

lack of prognostic certainty.

Neonatal Palliative Care

In newborns affected by life-threatening or

life-limiting conditions, when prolonging survival is no longer a goal,

a plan of care focused on the infant’s comfort is essential. These

strategies identify and address the basic needs of the newborn such as

bonding, maintenance of body temperature, relief of hunger/thirst, and

alleviation of discomfort. It is a multidisciplinary care given the

complex needs of infants and their families. Professionals like social

workers, workers from non-governmental sector, psychologists, child life

specialists, and spiritual representatives need to be actively involved

in the care to address psychosocial, financial, emotional, practical,

and spiritual needs of the family.

It is no surprise that parents of babies who have

received palliative services are more likely to be satisfied with the

care compared with parents whose infant did not receive it [14]. Thus,

the authors feel that there is an urgent requirement to standardize

neonatal palliative care practices and educate caregivers regarding

palliative care.

Withdrawal and Withholding of Care

Both ethicists and clinicians generally accept that

there is no significant ethical difference between withholding and

withdrawing intensive care measures [15]. However, for some parents

withdrawing is more difficult than withholding intensive care measures.

This may be secondary to increased emotional attachment as time

progresses. Proper understanding of this concept between parents and

clinicians, can lead to initiation of resuscitation in uncertain cases

with an option kept open to withdraw care if the situation warrants it.

In fact, the authors feel that such a pathway should be preferred

because with the passage of time a better clinical picture is formed to

base the decision.

Available Guidelines

The European Resuscitation Council 2015 guidelines

mention a variation of opinions regarding aggressive therapies in such

babies. Parents desire to participate in a larger manner in the decision

to resuscitate and continue life support. Local survival and outcome

data are essential to appropriately guide and counsel the parents [16].

The American Academy of Pediatrics/ American Health Academy’s 2015

resuscitation guidelines takes 25 weeks’ gestation as a cut-off point.

It cautions into considering various factors that can affect survival,

and using region-specific guidelines while counselling parents and

constructing a prognosis [17].

The 2017 consensus of American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and Society of Maternal-Fetal

Medicine on Pre-viable birth recommends resuscitation from 24 0/7 weeks

onwards and considers resuscitation between 22 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks

gestational age. Below 22 weeks, resuscitation is not recommended [18].

The guidelines further state that a stepwise approach considering

neonatal circumstances and parental wishes is appropriate. Care

decisions should be re-evaluated regularly and potentially redirected

based on the evolution of the clinical situation.

Clinicians also use certain tools to predict the

outcome of babies especially those in the grey zone. One of the most

commonly used models is the NICHD Neonatal Research Network tool that is

based on prospectively collected large data of extremely premature

infants [19]. There are some fallacies of such models. Most importantly,

gestational age, generally a key component in these models may not be

known accurately in all cases. The major problem by defining outcomes

based on completed weeks is that it eliminates the differences between a

fetus at 23 0/7 weeks and 23 6/7 weeks of gestation, as well as the

similarities between a fetus at 23 6/7 weeks and 24 0/7 weeks of

gestation. The inaccuracy of ultrasound-estimated fetal weight also

introduces a degree of uncertainty to the prediction of newborn outcomes

[18]. Lastly, the response of an individual neonate to resuscitation

cannot be predicted.

Thus, when a specific estimated probability for an

outcome is offered, it should be stated clearly that this is an estimate

for a population and not a prediction of a certain outcome for a

particular patient in a given institution.

Complexity of the Indian Scenario

In India, the scope and extent of medical services

ranges across a spectrum from poor healthcare to the best in the world.

In situations where appropriate care is not available, it would be

ethically correct that the parents should be given a choice to seek care

elsewhere.

The turmoil between ethics, logic and progress is

deep-rooted and intense in India. In addition to expenses being out of

pocket, we have cultural norms, which define who pays for first delivery

or second delivery, decisions to treat or not to treat are taken by an

extended family, the health care personnel are fewer in number and are

poorly trained in ethics as well as communication. Even proper

documented communication may be refuted by parents as we see in a

recently published paper from India [20]. In addition, India is a

cultural melting pot with multiple religions and sects with varying

approaches to births and deaths and often with gender preferences. In

such a scenario, making a blanket prescription for periviability is a

prescription for disaster.

There is an urgent need for a national consensus for

management of periviable babies and development of a database to collect

outcomes in this group. Analyzing the facts of neonatal survival,

morbidity and impact on families, we feel that each newborn should be

treated individually. The predefined gestational age limits should be

replaced with a more proactive approach. The neonatologist must develop

a personal approach towards decision-making.

1. Raju TN, Mercer BM, Burchfield DJ, Joseph GF Jr.

Periviable birth: executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice

Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human

Development, Society for Maternal- Fetal Medicine, American Academy of

Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1083-96.

2. Lubchenco LO, Searls DT, Brazie JV. Neonatal

mortality rate: relationship to birth weight and gestational age. J

Pediatr.1972;81:814-22.

3. Koops BL, Morgan LJ, Battaglia FC. Neonatal

mortality risk in relation to birth weight and gestational age: update.

J Pediatr.1982;101:969-77.

4. Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook

AR, Walsh MC, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of

Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Neonatal

outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research

Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126:443-56.

5. Costeloe KL, Hennessy EM, Haider S, Stacey F,

Marlow N, Draper ES. Short term outcomes after extreme preterm birth in

England: comparison of two birth cohorts in 1995 and 2006 (the EPICure

studies). BMJ. 2012;345:e7976.

6. Moore GP, Lemyre B, Barrowman N, Daboval T.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 4 to 8 years of children born at 22 to 25

weeks’ gestational age: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:967-74.

7. Bolisetty S, Legge N, Bajuk B, Lui K. Preterm

infant out- comes in New South Wales and the Australian Capital

Territory. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory Neonatal

Intensive Care Units’ Data Collection. J Paediatr Child Health.

2015;51:713-21.

8. Moore T, Hennessy EM, Myles J, Johnson SJ, Draper

ES, Costeloe KL, et al. Neurological and developmental out- come

in extremely preterm children born in England in 1995 and 2006: the

EPICure studies. BMJ. 2012;345:e7961.

9. Younge N, Goldstein RF, Bann CM, Hintz SR, Patel

RM, Smith PB, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of

Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Survival

and neurodevelopmental outcomes among periviable infants. N Engl J Med.

2017; 376:617-28.

10. Lee SK, Penner PL, Cox M. Comparison of the

attitudes of healthcare professionals and parents toward active

treatment of very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics.1991;88:110-4.

11. President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical

Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Deciding to

Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment: A Report on the Ethical, Medical, and

Legal Issues in Treatment Decisions. Washington, DC: Government Printing

Office; 1983.

12. Singh J, Fanaroff J, Andrews B, et al.

Resuscitation in the "gray zone" of viability: Determining physician

preferences and predicting infant outcomes. Pediatrics. 2007;120:519-26.

13. Gillam L. The zone of parental discretion: An

ethical tool for dealing with disagreement between parents and doctors

about medical treatment for a child. Clin Ethics. 2016; 11:1-8.

14. Petteys AR, Goebel JR, Wallace JD, Singh-Carlson

S. Palliative care in neonatal intensive care, effects on parent stress

and satisfaction: a feasibility study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care.

2015;32:869-75.

15. Mercurio MR. The ethics of newborn resuscitation.

Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:354-63.

16. Wyllie J, Bruinenberg J, Roehr CC, Rüdiger M,

Trevisanuto D, Urlesberger B. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines

for Resuscitation 2015. Resuscitation. 2015;95:249-63.

17. Wyckoff MH, Aziz K, Escobedo MB, Kapadia VS,

Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, et al. Part 13: Neonatal Resus-citation:

2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation.

2015;132:S543-60.

18. American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care

consensus No. 6: Periviable Birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e187-e99.

19. Tyson JE, Parikh NA, Langer J, Green C, Higgins

RD. Intensive care for extreme prematurity - moving beyond gestational

age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1672e8.