|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2015;53: 15-17 |

|

Centralized Newborn Hearing Screening in

Ernakulam, Kerala – Experience Over a Decade

|

|

Abraham K Paul

Convenor, Newborn Hearing Screening Programme-IAP,

Kochi, Kerala.

Correspondence to: Dr Abraham K Paul, Pediatrician,

Cochin Hospital, Cochin-16, Kerala.

Email: abrahamkpaul@gmail.com

|

|

A two-stage centralized newborn

screening program was initiated in Cochin in January 2003. Infants are

screened first with otoacoustic emission (OAE). Infants who fail OAE on

two occasions are screened with auditory brainstem response (ABR). All

Neonatal intensive care unit babies undergo ABR. This successful model

subsequently got expanded to the whole district of Ernakulam, and some

hospitals in Kottayam and Thrissur districts. Over the past 11 years,

1,01,688 babies were screened. Permanent hearing loss was confirmed in

162 infants (1.6 per 1000). This practical model of centralized newborn

hearing screening may be replicated in other districts of our country or

in other developing countries.

Keywords: Disability, Hearing loss, Neonate,

Prevention, Universal newborn hearing screening.

|

|

Hearing loss is one of the most common anomalies,

occurring in 1-2 per 1000 infants [1]. The incidence is considerably

higher in infants in the Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (1-2 cases

per 200 infants) [2]. Left undetected, hearing impairment in infants can

negatively affect speech and language acquisition, academic achievement

and social and emotional development. These negative effects can be

diminished and even eliminated through early intervention at or before 6

months of age [3]. Neonatal hearing loss and its developmental

consequences are measurable before the age of 3 years [4-6]. It is an

established fact that language development is positively and

significantly affected by age of identification of hearing loss and age

of initiation into intervention services.

Reliable screening tests that minimize referral rates

and maximize sensitivity and specificity are available. The goal of

Universal neonatal hearing screening is to maximize linguistic and

communicative competence and literacy development for children who are

hard of hearing or deaf.

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 1999

advocated Universal new born hearing screening programme and remedial

intervention which is being practiced in most of the developed

countries. In a developing country like India, the risk of infants to

develop these difficulties is obviously more [8,9]. In interventional

programs, the Indian studies mostly cite the screening facilities

available to newborns brought in to tertiary referral hospitals [10-12].

A hearing screening equipment facility in every hospital with maternity

units today may not be a viable proposition. In this background, a

practical interventional model was conceived for the city of Cochin

(which has 20 hospitals with maternity units) in January 2003.

Centralized Newborn Hearing Screening

A two-stage screening protocol with Otoacoustic

emission (OAE) as the first screen, followed by Auditory brainstem

response (ABR) for those who fail the second OAE screen was introduced.

All NICU babies underwent ABR. With three portable screening machines

and three screeners, 20 hospitals in the city of Cochin became partners

in the program. This practical interventional model of centralized

newborn screening was found to be a cost-effective solution to the

newborn hearing screening of Cochin city [13]. After a decade of

successful operation, it was decided to expand the program to whole of

Ernakulam District with 91 hospitals, and part of hospitals in

neighboring Kottayam and Thrissur districts. Thirteen hospitals had

their own inhouse screening facility. Five more machines were procured

and another five personnel trained and appointed. The program became

operational in August 2014. The programme is co-ordinated by a speech

and language pathologist and weekly assessment meeting is convened with

the staff by the convenor.

Screening facility operates out of Child Care Centre,

which is also the secretariat of IAP Cochin Branch. Personnel with basic

knowledge in computer and good communication skills were chosen, given

basic training in hearing screening and also skill to gather information

of high risk criteria, if any, from parents/hospital staff/ hospital

records. The screening personnel visit each hospital daily/alternate

days/twice-a-week/weekly depending upon the number of births in that

particular hospital. Daily screening was carried out in hospitals which

had more than 200 births, alternate day screening in hospitals with

100-200 births and twice weekly or weekly screening in hospitals with

births less than 100 per month. On an average, each staff screen about

10-20 babies per day depending upon the hospital delivery rate. If

abnormal OAE, it is repeated at 6 weeks on the 1 st

immunization visit. If again abnormal, ABR is done for confirmation

followed by full audiological evaluation and remediation. All NICU

babies undergo ABR testing. In babies with abnormal ABR, detailed

enquiry is made to identify and record any risk factors [14]. Any baby

missing screening before hospital discharge is called for OAE test on

the first immunization visit [13]. The salary for staff, cost of

equipments and consumables are met from the testing fees (Rs.150 per

baby) collected.

There were a total of number of 1,20,630 births in 78

hospitals over the period from January 2003 to January 2015, out of

which 82,268 babies underwent screening before discharge and 19,420

babies at 6 weeks. The number of births in individual hospitals varied

from 15 per month to 275 per month. Two hospitals had births more than

200, 9 had between 100 – 200 and 67 hospitals below 100. A total of

18,942 babies missed screening and the majority were from hospitals

where screening was done on a weekly basis.

In 13 major hospitals that had in-house OAE screening

facility, the screening was done by audiologists and they had their own

ABR facility. Out of 78 hospitals where screening was done by our team,

11 had ABR facility and the others were depending on nearby private

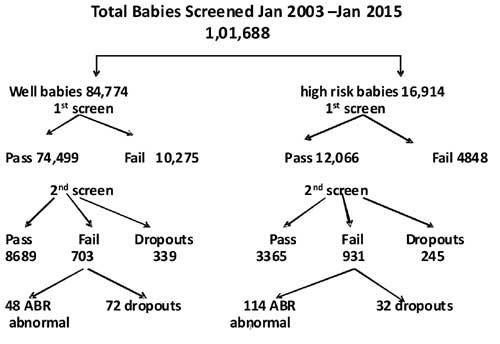

hospitals or ENT/Audiology centers for the same. Out of 1,01,688 babies

screened, 16,914 were in the high-risk group and 84,774 were not in

high-risk group. Out of 84,774 babies in the non-high risk group, 339

were dropouts for second OAE Screen and 72 for ABR screening. They

failed to return even after repeated phone calls. In the high-risk

group, 245 were dropouts for second OAE screen and 32 were dropouts for

ABR screening (Fig. 1). The mean interval between

OAE fail and ABR testing was four weeks.

|

|

Fig. 1 Result of newborn hearing

screening for high-risk and well babies.

|

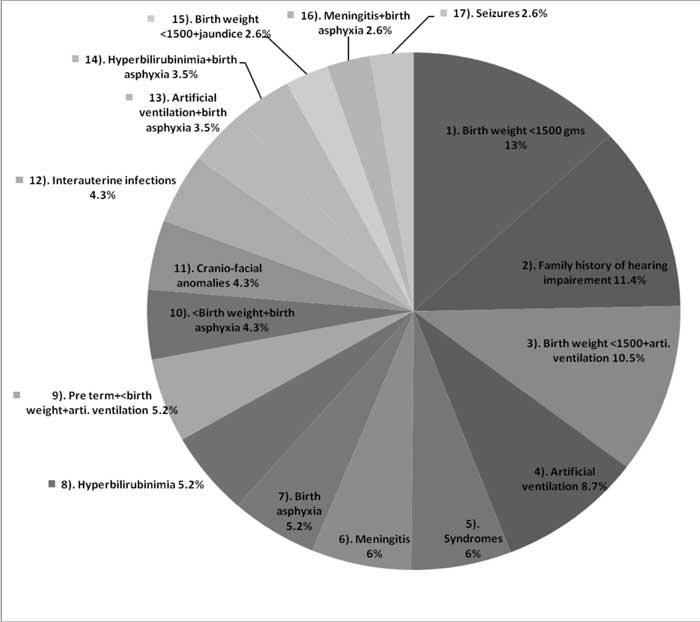

48 infants (29.6%) had no risk factors and 114 babies

had one or more risk factors. Risk factors for hearing loss were

identified by using the guidelines of the Joint Committee on Infant

Hearing 2000 position statement [14]. The distribution of different risk

factors are presented in Fig. 2.

|

|

Fig. 2. Distribution of risk factors

according to guidelines of Joint Committee on Infant Hearing

2000 position statement.

|

The most common risk-factor was low birth weight

(13%) followed by familial deafness (11%). Low birth weight coupled with

mechanical ventilation contributed to 10.5% and mechanical ventilation

alone accounted for 8.8%. Hyperbilirubinimia alone contributed to 5.3%

cases.

Ernakulam District Experience

Out of 1,01,688 cases screened over the past 11

years, 84,774 were the well-baby nursery group. Out of that, 10,275

failed the first OAE screen. This 12% failure may be an acceptable

figure because of early screening on Day 2 or 3 of delivery in view of

the early discharge practice. 72 dropouts for ABR out of 703 who failed

the second OAE screen is a matter of concern. A matter of more concern

is the drop-outs in the high risk group even after repeated reminders

(245 out of 4848 who failed the first OAE screen and the 32 dropouts

after the second OAE screen). The incidence of congenital deafness in

well baby nursery in our study is 0.6 per thousand as compared to 1 in

1000 in the literature [1]. In the high-risk population of 16,914 babies

screened, 114 babies were detected to have congenital hearing loss with

an incidence of 0.7 per 100 as compared to 1-2 cases per 200 [2].

The most common cause of congenital deafness in our

series was birth weight <1500 gms (13%) followed by familial deafness in

11%. This is in contrast to observation by Declau, et al. [7]

screening 87,000 newborns in a tertiary care center in Belgium, where

the most common etiological factor was familial deafness accounting for

10.6%. 35 out of 114 cases of permanent congenital hearing loss had more

than 1 risk factors (30%).

Conclusion

Universal Newborn Hearing Screening (UNHS) has become

a standard practice in most developed countries. The identification of

all newborns with hearing loss before six months has now become an

attainable and realistic goal, as our program of universal newborn

hearing screening in Ernakulam District crosses one lakh babies. The

concept of a centralized new born hearing screening model to cater to

all hospitals in the districts is worth replicating. It takes away the

financial burden of each hospital investing for the screening equipment.

Follow up of positive cases and drop-outs is made easier with the

central reporting and monitoring system. With unified strength of

pediatricians, IAP city/district branches could take initiative to

replicate this model in their respective towns or districts.

References

1. Parving A, Hauch AM, Christensen B. Hearing loss

in children: epidemiology, age at identification and causes through 30

years [in Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2003;165:574-9.

2. Van Straaten HL, Tibosch CH, Dorrepaal C, Dekker

FW, Kok JH. Efficacy of automated auditory brainstem response hearing

screening in very preterm newborns. J Pediatr. 2001;138:674-8.

3. Yoshinaga-Itano C, Coulter D, Thomson V.

Developmental outcomes of children with hearing loss born in Colorado

hospitals with and without universal newborn hearing screening programs.

Semin Neonatol. 2001;6:521 -9.

4. Yoshinaga-Itano C, Apuzzo ML. Identification of

hearing loss after age 18 months is not early enough. Am Ann Deaf.

1998;143:380-7.

5. Yoshinaga-Itano C, Apuzzo ML. The development of

deaf and hard of hearing children identified early enough through the

high risk registry. Am Ann Deaf. 1998;143:416-24.

6. Fortnum HM, Summerfieled AQ, Marshal DH, Davis A,

Bamford M. Prevalence of permanent childhood hearing impairment in

United Kingdom and implications for universal neonatal hearing

screening: Questioner based assertainment study. BMJ. 2001;323:536-40.

7. Declau F, AA Boudewayns, Jenneke Van deu Ende,

Peters A. Etiologic and audiologic evaluations after universal neonatal

hearing screening: analysis of 170 referred neonates. Pediatrics.

2008;121:1119-1126.

8. Report of the Collective Study on Prevalence and

Etiology of Hearing Impairment. New Delhi: ICMR and Department of

Science; 1983.

9. Kacker SK. The Scope of Pediatric Audiology in

India. In: Deka RC, Kacker SK, Vijayalakshmi B, eds. Pediatric

Audiology in India, 1st ed. New Delhi: Otorhinolaryngo-logical Research

Society of AIMS; 1997.p.20.

10. Nagapoonima P, Ramesh A, Srilakshmi, Rao S,

Patricia PL, Gore M. Universal hearing screening. Indian J Pediatr.

2007;74:545-8.

11. Vaid N, Shanbag J, Nikam R, Biswas A. Neonatal

hearing screening – The Indian experience. Cochlear Implants Int.

2009;10:111-4.

12. Ramesh A, Nagapoornima M, Srilakshmi V, Dominic

M. Swarnarekha. Guidelines to Establish a Hospital-based Neonatal

Hearing Screening Programme in the Indian Setting. JAIISH.

2008;27:105-9.

13. Paul AK. Early identification of hearing loss and

centralized newborn hearing screening facility-The Cochin experience.

Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:356-9.

14. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing; American

Academy of Audiology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American

Speech-Language-Hearing Association; Directors of Speech and Hearing

Programmes in State Health and Welfare Agencies. Year 2000 Position

Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and

Intervention Programmes. Pediatrics. 2000;106:798-817.

|

|

|

|

|