|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2012;49:

29-34 |

|

Body Mass Index Cut-offs for Screening for

Childhood Overweight and Obesity in Indian Children |

|

VV Khadilkar, AV Khadilkar, AB Borade and SA Chiplonkar

From the Department of Pediatrics, Hirabai Cowasji

Jehangir Medical Research Institute, Jehangir Hospital, Pune, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Anuradha Khadilkar, Growth and

Pediatric Endocrine Unit, Hirabai Cowasji Jehangir Medical Research

Institute, Jehangir Hospital, 32, Sassoon Road, Pune 411 001, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: July 30, 2010;

Initial review: September 3, 2010;

Accepted: January 14, 2011.

Published online: 2011, May 30.

PII:S09747559INPE1000147-1

|

Objective:

To develop age and sex

specific cut- offs for BMI to screen for overweight and obesity in Indian

children linked to an adult BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m2 respectively, using

contemporary Indian data.

Design: Cross-sectional.

Setting: Multicentric, School based.

Participants: 19834 children were measured from 11

affluent schools from five major geographical regions of India. Data were

analyzed using the LMS method, which constructs growth reference

percentiles adjusted for skewness.

Results: Compared to the cut-offs suggested for

European populations and those by the Indian Academy of Pediatrics 2007

Guidelines, the age and sex specific cut off points for body mass index

for overweight and obesity for Indian children suggested by this study are

lower.

Conclusions: Contemporary cross-sectional age and

sex specific BMI cut-offs for Indian children linked to Asian cut-offs of

23 and 28 kg/m2 for the assessment of risk of overweight and

obesity, respectively are presented.

Key words: Adult equivalent BMI, Childhood, Cut-off, India,

Obesity, Overweight.

|

|

The unabated rise in the

prevalence of overweight in children and adolescents is one of the most

alarming public health issues facing the world today [1]. Among

Indian children, various studies report

the magnitude of overweight to be from 9 to 27.5% and that

of obesity from 1 to 12.9% [2-6].

Obesity increases the risk for many chronic diseases

including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease, and decreases the overall quality of life [7-9].

Therefore, it is imperative to identify the at risk individuals at an

early stage.

Allowing for the ease of measuring height and weight in

the field setting, Body Mass Index (BMI) is believed to be an acceptable

indicator of the risk of overweight in children and adolescents [10]. A

cut-off point of 30 kg/m 2

and 25 kg/ m2 are

recognized internationally as a definition of obesity and overweight in

adults. However, BMI in children changes substantially with age, thus,

age-specific cut-off points are needed. The 85th and 95th percentile have

been used as cut-offs to define overweight and obesity, respectively in

children [11].

The pattern of growth of a population changes over time

and hence growth references should be updated regularly, particularly for

countries in nutritional transition [12]. However, our multicentric growth

survey on 5 to 17 year-old affluent urban Indian children show that

compared to the previously available nationally representative data, boys

and girls were heavier at all ages [13]. Using growth references based on

a descriptive sample of a population that reflects a secular trend towards

overweight and obesity may result in the underestimation of overweight and

obesity. Therefore, it is crucial to find a method by which the influence

of unhealthy weight on BMI reference curves is avoided.

The 85th and 95th percentile that are used as cut-off

points for overweight and obesity in children are arbitrary and are not

linked to obesity related health risks. Unfortunately, identifying cut-off

points in children is more difficult since they have less disease related

to obesity than adults. A workshop organized by the International Obesity

Task Force (IOTF) proposed that adult cut-off points be linked to BMI

percentiles for children to provide child cut-off points [14]. Lower BMI

cut-offs of 23 and 28 kg/m 2

have been suggested for overweight and obesity for Asian adults, as they

are more prone to adiposity and central obesity at a lower BMI than their

western counterparts. Thus, in the present study, we have used an external

quantitative criterion, i.e. the adult BMI equivalent of 23 and 28 kg/m2

as advised for Asian populations, to derive cut-offs for screening for

risk of overweight and obesity for Indian children [15]. The specific aim

of this study was to develop age and sex specific cut-offs for BMI for

risk of overweight and obesity for 5-17 year old Indian children linked to

an adult BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m2,

respectively using contemporary Indian data and to examine the validity of

the cut-offs of 25 and 30 kg/m2

used by western populations.

Methods

We used data on BMI from a nationally representative,

multicentric, cross sectional survey conducted from June 2007 to January

2008 [13]. The Indian Academy of Pediatrics divides India into 5 zones,

i.e. North, South, East, West, and Central. We selected ten study sites

from these regions (Delhi, Chandigarh, Chennai, Bangalore, Kolkata,

Mumbai, Pune, Baroda, Hyderabad and Raipur). Study staff identified

nutritionally well-off areas in above cities (based on per capita income)

all over India and made a list of schools catering to children of

socioeconomically welloff families [16]. Three schools were selected (from

each zone) from those chosen by generating random numbers (yearly fees

≥  10,000).

Permission for the study was obtained from 11 schools; two schools each

from in east, north, central and south zones and 3 schools from west zone

participated in this study. 10,000).

Permission for the study was obtained from 11 schools; two schools each

from in east, north, central and south zones and 3 schools from west zone

participated in this study.

Standing height was measured using a portable

stadiometer (Leicester Height Meter, Child Growth Foundation, UK, range

60-207cm). Weight was measured using portable electronic weighing scales

(Salter, India) accurate to 100 g. Children’s age was derived using school

records.

Measurements were performed by 17 graduate observers

acquainted with the cities and local language. They were trained as per

study protocol, and given written instructions about the calibration of

instruments, measurement techniques, and data entry formats.

Inter-observer and intraobserver coefficients of variation were both

<0.01(1%).

The cleaned data were then analyzed using the LMS

method, which constructs growth reference percentiles adjusted for

skewness [17]. Each growth reference is summarized by 3 smooth curves

plotted against age representing the median (M), the coefficient of

variation (S) and the skewness (L) of the measurement distribution [18].

The L, M, and S curves convert measurements to exact SD scores using the

formula:

SD score= Measurement /M(t)L(t)-1/ S(t)L(t)

Where measurement is the child’s measurement (height or

weight) and L(t), M(t) and S(t) are values read from the smooth curves for

the child’s age t and sex. The models were checked for goodness of

fit using the detrended Q-Q plot, Q Tests and worm plots [19].

Queries about inconsistent data were checked against

the original data collection forms and obviously erroneous measurements

were excluded (1.1%, n=221). Subjects aged <5 years or >18 years

were also excluded (n=922), as were data where the Z score

exceeded ± 5SD (n=25) [13].

Percentile curves for BMI corresponding to the 3rd,

25th, 50th, 85th and 95th percentile were constructed using the LMS method

[18]. Additionally, percentile curves passing through 23 and 28 kg/m 2

at 18 years for boys and girls were constructed. The percentile curves

passing through the points of 23 and 28 kg/m2

at 18 years are the suggested cutoff points for risk of overweight or

obesity in childhood.

For validating the cut-offs, a total of 250 children

from schools and a tertiary care pediatric endocrine clinic were selected

so that the children were distributed over the whole range of BMI

categories (adult equivalent BMI of <23, 23-25, 25-28, 28-30 and >30). A

total of 208 children agreed to participate in the study (mean age

11.4±2.9 years, 104 boys). Children from the endocrine clinic had undergone

a detailed work up to ascertain that they had no primary endocrine cause

of obesity and had only nutritional obesity. All children were assessed

with respect to anthropometry (weight, height, BMI and waist circumference

and waist to hip ratio for abdominal obesity), blood pressure and blood

parameters (fasting triglycerides, high density lipoprotein cholesterol

and plasma glucose. Children were classified as normal and hypertensive

according to age, gender and height [20]. As per the definition of

National Cholesterol Education Program III (NCEP), children were

categorized according to the number of risk factors of metabolic syndrome

(MS) detected viz. abdominal obesity (waist circumference >90th

percentile [21], hypertriglyceridemia (≥110

mg/dL), low high density lipoprotein cholesterol (≤40mg/dL),

hypertension (≥90th

percentile according to age, gender and height) and hyperglycemia (fasting

blood glucose ≥100

mg/dL) [22]. Children were categorized as normal, having one risk (MS-1)

and having ≥2

risk factors (MS>1 risk) [18]. The children were divided into five

categories using the cut-offs suggested by the current study as follows:

children with adult equivalent BMI of <23, 23-25, 25-28, 28-30 and ≥ 30 kg/m 2.

Results

We measured 19,834 children from 11 affluent schools.

After cleaning the data (removal of erroneous measurements and subjects

below 5 and above 18 years of age), 18,666 children, (10,496 boys and

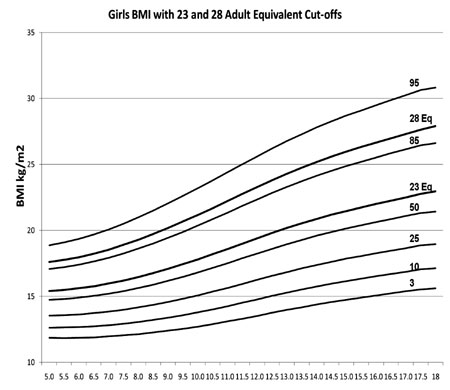

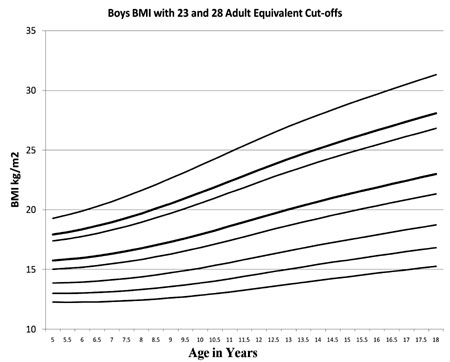

8,170 girls) from 5 zones of India were analyzed. Figure

1 and 2 show smoothed BMI percentile curves for Indian boys and

girls aged 5-17 years with the 3rd, 10th, 25th, 50th, 85th and 95th

percentiles, with two additional percentiles corresponding to a BMI of 23

and 28 kg/m 2 at 18 years. BMI

of 23 kg/m2 at 18 years age in

boys corresponds to the 64th percentile, and in girls to the 63rd

percentile. A BMI of 28 kg/m2

at 18 years age is on the 89th percentile in both boys and girls.

|

|

Fig. 1 BMI percentile curves for Indian

boys from 5-17 years with the 3 rd,

10th, 25th, 50th, 85th and 95th percentiles, with two additional

percentiles corresponding to a BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m2 at

18 years. |

|

|

|

Fig. 2 BMI percentile curves for Indian

girls from 5-17 years with the 3 rd,

10th, 25th, 50th, 85th and 95th percentiles, with two additional

percentiles corresponding to a BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m2 at

18 years. |

TABLE I Age specific BMI cut-off values for Risk of Overweight and Obesity Corresponding

to Adult Equivalent BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m2 at Age 18 Years for Indian Boys and Girls

| Age (years) |

Adult Equivalent |

|

BMI 23kg/m2 |

BMI 28kg/m2 |

| Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

| 5 |

15.8 |

15.4 |

17.9 |

17.6 |

| 5.5 |

15.9 |

15.5 |

18.1 |

17.8 |

| 6 |

16 |

15.6 |

18.4 |

18 |

| 6.5 |

16.1 |

15.8 |

18.7 |

18.2 |

| 7 |

16.3 |

16 |

19 |

18.5 |

| 7.5 |

16.5 |

16.2 |

19.3 |

18.9 |

| 8 |

16.8 |

16.5 |

19.7 |

19.3 |

| 8.5 |

17 |

16.8 |

20.1 |

19.7 |

| 9 |

17.3 |

17.1 |

20.5 |

20.2 |

| 9.5 |

17.6 |

17.4 |

21 |

20.7 |

| 10 |

17.9 |

17.8 |

21.4 |

21.2 |

| 10.5 |

18.3 |

18.2 |

21.9 |

21.7 |

| 11 |

18.6 |

18.6 |

22.4 |

22.2 |

| 11.5 |

19 |

19 |

22.9 |

22.8 |

| 12 |

19.3 |

19.4 |

23.3 |

23.3 |

| 12.5 |

19.7 |

19.8 |

23.8 |

23.8 |

| 13 |

20 |

20.2 |

24.3 |

24.3 |

| 13.5 |

20.4 |

20.5 |

24.7 |

24.8 |

| 14 |

20.7 |

20.9 |

25.1 |

25.2 |

| 14.5 |

21 |

21.2 |

25.5 |

25.6 |

| 15 |

21.3 |

21.5 |

25.9 |

26 |

| 15.5 |

21.6 |

21.7 |

26.3 |

26.3 |

| 16 |

21.9 |

22 |

26.7 |

26.7 |

| 16.5 |

22.2 |

22.3 |

27 |

27 |

| 17 |

22.4 |

22.5 |

27.4 |

27.3 |

| 17.5 |

22.7 |

22.8 |

27.7 |

27.6 |

| 18 |

23 |

23 |

28.1 |

27.9 |

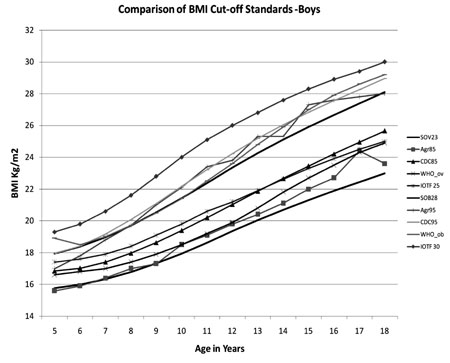

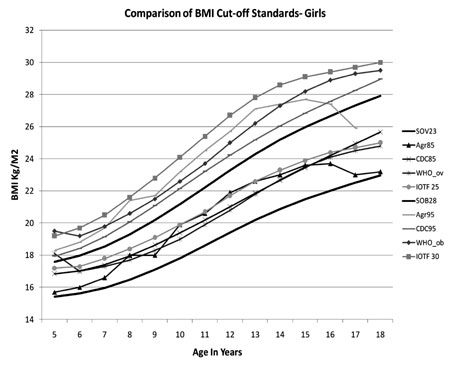

Table I gives suggested age specific BMI

cut-off values corresponding to adult equivalent BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m 2

at age 18 years age for Indian boys and girls. Fig. 3

and Fig. 4 show a comparison between the BMI

cut-off’s for overweight and obesity as suggested by the IAP 2007

guidelines, the CDC 2000, WHO charts, the IOTF and the present study for

boys and girls. Except at five years of age, the IOTF cut-offs are highest

and those suggested by the current study are the lowest.

|

|

Fig. 3 Comparative BMI cut-off’s

for overweight as suggested by the IAP 2007 guidelines, the CDC

2000, WHO charts, the IOTF and the present study for boys. |

|

|

Fig. 4 Comparative BMI cut-off’s for

overweight and obesity as suggested by the IAP 2007 guidelines, the

CDC 2000, WHO charts, the IOTF and the present study for boys. |

Figure 4 shows the percentage of children who

were normal, had one risk and had greater than one risk for metabolic

syndrome in the five BMI categories (<23, 23-25, 25-28, 28-30 and >30) in

the group of 208 children assessed for validating the cut-offs . While

around 5% of the children with an adult equivalent BMI of less than 23 had

one or more than one risk factor for MS, this percentage increased

progressively with increasing BMI category (43%, 47%, 72% and 80% in the

BMI category of adult equivalent BMI of 23-25, 25-28, 28-30 and >30 kg/m 2,

respectively).

Discussion

We have presented age and sex-specific BMI cut-offs for

Indian children, based on a reference population of urban affluent

children measured from June 2007 to January 2008, such that the cut-offs

are linked to the adult accepted BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m 2

for overweight and obesity for Asians. The BMI values suggested by this

study are comparable and at certain ages lower than those suggested by the

IAP 2007 Guidelines [22] and lower than other suggested cut-offs [23-25].

With the rising incidence of childhood obesity in

children the world over using the 85th and 95th percentile of the

population as cut-offs for overweight and obesity is likely to result in

underestimation of childhood obesity. Various methods have thus been used

to avoid the influence of unhealthy weights for length/height on BMI

reference curves. While constructing the WHO curves for school-age

children from 5-18 years observations falling above +2 SD of the

sample median for weight for height were excluded prior to constructing

the charts [23]. When the CDC 2000 growth curves were developed, data from

the NHANES III survey for children greater than or equal to 6 years of age

were excluded from the charts for weight-for-age, weight-for-stature, and

BMI-for-age as the prevalence of overweight was nearly double that seen in

earlier surveys [1]. In the present study we did not use the approach

suggested by the WHO because the cut-off of +2 SD for weight for height is

arbitrary and also for the technical reason that LMS data for calculation

of SD scores for weight-for-height for children from 5-18 years by the WHO

were not available. We also could not use the approach used by the CDC, as

all children in the present study were measured in a time period of 8

months and omitting data from the dataset as per an arbitrary cut-off

would have disturbed the regional representation of the study. Thus, we

used an external criterion, adult-linked BMI, to generate BMI cut-off

values for 5-17 year-old Indian children.

To develop an internationally acceptable definition of

childhood overweight and obesity that was less arbitrary and more

internationally acceptable, Cole, et al. used six large nationally

representative cross-sectional growth studies and for each survey

percentile curves were drawn that at age 18 years passed through the

widely used cut-off points of 25 and 30 kg/m 2

for adult overweight and obesity [26]. However, a WHO expert consultation

has reviewed scientific evidence which suggests that Asian populations

have different associations between BMI, percentage of body fat, and

health risks compared to Europeans. They concluded that the proportion of

Asians with a highrisk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease is

substantial at BMIs lower than the existing WHO cut-off of 25 kg/m2

for overweight [27-29]. Studies have also indicated that body fat

percentage in Indian children and adolescents as measured by

bio-electrical impedance analyser and by dual emission x-ray

absorptiometry is higher than in their Western counterparts [30]. Snehlata,

et al. have thus suggested that a cut-off of 23 and 28 kg/m2

be used for classifying Indian adults as overweight and obese,

respectively [31]. In a study to evaluate definitions of the metabolic

syndrome in adult Asian Indians Misra, et al., have also suggested

that the BMI cut-offs be lowered to 23 kg/m2,

they additionally suggest lowering the waist circumference cut-offs to 90

cm in men and 80 cm in women, and the subscapular skinfold thickness

cut-off to18 mm [32,33]. Validating the cut-offs suggested by this study

on 250 children, we found that around 43% children in the adult equivalent

BMI category of 23-25 kg/m2

had ≥1 risk

factor for development of the MS. Thus, if the adult equivalent of 25 kg/m2

was used as a cut-off for overweight, these children would be misdiagnosed

as normal. Similarly, around 73% children in the BMI category of adult

equivalent of 28-30 kg/m2 had ≥1 risk factor

for developing the MS and would be classified as overweight rather than

obese if an adult equivalent cut-off of 30 kg/m2

were to be used.

In a study to evaluate carotid arterial stiffness in

obese and healthy Indian children, Pandit, et al. have reported

that the stiffness, pulse wave velocity and elastic modulus of the right

carotid artery were significantly higher in obese and overweight children

suggesting that functional changes in the carotid artery start very early

in life [31]. Thus, there is a need to identify children at a risk of

overweight and obesity at an early age to avoid further cardiovascular

complications.

In conclusion, we have presented age and sex-specific

BMI cut-offs for Indian children, based on a reference population of urban

Indian affluent children, such that the cut-offs are linked to the adult

accepted BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m 2

for overweight and obesity for Asians. The BMI values suggested here are

likely to pick up obesity early and prevent future complications occurring

due to childhood obesity.

Acknowledgments: Professor T J Cole, ScD, MRC

Centre of Epidemiology for Child Health, UCL Institute of Child Health,

London, UK for his advice on the project.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study

design, data collection, data analyses, and manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: None stated; Funding:

None.

|

What is Already Known?

•

Asian Indians are a high risk

group for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease at BMIs lower

than the international WHO cut-off of 25 kg/m2 for overweight and

30 kg/m2 for obesity.

What This Study Adds?

•

Age and sex-specific BMI cut-offs for Indian children from

5-17 years are presented, such that the cut-offs are linked to the

adult accepted BMI of 23 and 28 kg/m2 for overweight and obesity

for Asians.

|

References

1. Weiss R, Caprio S. The metabolic consequences of

childhood obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:405-19.

2. Kapil U, Singh P, Pathak P, Dwivedi SN, Bhasin S.

Prevalence of obesity among affluent adolescent school children in Delhi.

Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:365-8.

3. Sidhu S, Kaur N, Kaur R. Overweight and obesity in

affluent school children. Ann Hum Biol. 2006;33:255-9.

4. Chhatwal J, Verma M, Rair SK. Obesity among

pre-adolescent and adolescents of a developing country (India). Asia Pac J

Clin Nutr. 2004;13:231-5.

5. Sharma A, Sharma K, Mathur KP. Growth pattern and

prevalence of obesity among affluent school children in Delhi. Public

Health Nutr. 2007;10:485-91.

6. Bose K, Bisai S, Mukhopadhyay A, Bhadra M.

Overweight and obesity among affluent Bengalee schoolgirls of Lake Town,

Kolkata, India. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3:141-5.

7. Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Wattigney WA, Harsha DW.

Obesity and cardiovascular risk in children. Ann NY Acad Sci.

1993;699:93103.

8. Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Newman WP, Tracy

RE, Wattigney WA. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors

and athero sclerosis in children and young adults. The Bogalusa heart

study. New Engl J Med. 1998;338:16506.

9. Mahoney LT, Burns TL, Stanford W. Coronary risk

factors measured in childhood and young adult life are associated with

coronary artery calcification in young adults: the Muscatine study. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:27784.

10. Malina RM, Katzmarzyk PT. Validity of the body mass

index as an indicator of the risk and presence of overweight in

adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:1316S.

11. Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Obesity Evaluation and

Treatment: Expert Committee Recommendations. The Maternal and Child Health

Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration and the Department of

Health and Human Services. Pediatrics. 1998;102:29

12. Buckler JMH. Growth disorders in Children. 1st ed.

London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1994.

13. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Cole TJ, Sayyad MG.

Cross-sectional growth curves for height, weight and body mass index for

affluent Indian children, 2007. Indian Pediatr. 2009; 46:477-89.

14. Bellizzi MC, Dietz WH. Workshop on childhood

obesity: summary of the discussion. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:1735.

15. Snehalata C, Vishwanathan V, Ramachandran A. Cutoff

value for normal anthropometric variables in Asian Indian adults. Diabetes

Care. 2003;26:1380-4.

16. Ministry of Urban Development (Lands Division),

Government of India. Letter No. J-220 11/1/91-LD.

17. Van’t Hof MA, Wit JM, Roede MJ. A method to

construct age references for skewed skinfold data,using Box-Cox

transformations to normality. Hum Biol. 1985;57:131-9.

18. Cole TJ, Green PJ. Smoothing reference

centilecurves: the LMS method and penalized likelihood. Stat Med.

1992;11:1305-19.

19. Van Buuren S, Fredriks, M. Worm plot: a simple

diagnostic device for modeling growth Reference curves. Stat Med.

2001;20,1259-77.

20. National High Blood Pressure Education Working

Group: The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of

high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics.

2004;114:555-76.

21. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection,

Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult

Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486-97.

22. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Choudhury P, Agarwal KN,

Ugra D, Shah NK. IAP growth monitoring guidelines for children from birth

to 18 years. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44: 187-97.

23. de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida

C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged

children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660-7.

24. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM,

Flegal KM, Mei Z, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United

States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 2002;246:1-190.

25. International Obesity Task Force. Obesity:

preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of WHO consultation on

obesity, Geneva, 3-5 June 1998. Geneva: WHO; 1998.

26. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH.

Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity

worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240-3.

27. Mckeigue PM, Shah B, Marmot MG. Relationship of

central obesity and insulin resistance with high diabetes prevalence and

cardiovascular risk in South Asians. Lancet. 1991;337:382-6.

28. Banerji MA, Faridi N, Atluri R, Chaiken RL,

Lebovitz HE. Body composition, visceral fat, leptin and insulin resistance

in Asian Indian men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84: 137-44.

29. Enas EA, Yusuf S, Mehta JL. Prevalence of coronary

artery disease in Asian Indians. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:945-9.

30. Pandit D, Chiplonkar S, Khadilkar A, Khadilkar V,

Ekbote V. Body fat percentages by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

corresponding to body mass index cutoffs for overweight and obesity in

Indian children. Clinical Medicine: Pediatrics. 2009;3:55-61.

31. Pandit D, Kinare A, Chiplonkar S, Khadilkar A,

Khadilkar V. Carotid arterial stiffness in overweight and obese Indian

children. J Pediatr Endocrinol and Metab.2011;24:97-102.

32. Misra A, Wasir JS, Pandey RM. An evaluation of

candidate definitions of the metabolic syndrome in adult Asian Indians.

Diabetes Care. 2005;28:398-403.

33. Misra A, Misra R, Wijesuriya M, Banerjee D. The

metabolic syndrome in South Asians: continuing escalation and possible

solutions. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:345-54.

|

|

|

|

|