Mala Bhalla,

Rashmi Sarkar

Priti Arun

Amrinder J. Kanwar

From

the Departments of Dermatology and Venereology &

*Psychiatry, Government Medical College & Hospital, Sector

32, Chandigarh 160 047, India.

Correspondence

to: Dr. Rashmi Sarkar, C/o. Mrs. C. Sarkar, Teachers’ Flats

No. 9, Sector 12, P.G.I. Campus, Chandigarh 160 012,

India. Email: [email protected]

Manuscript

Received: October 31, 2001;

Initial review completed: November 28, 2001;

Revision Accepted: September 27, 2002,

Trichotillomania,

though uncommon, is one of the causes of unexplained hair loss,

especially in children. Three girls in the age group of 4-6 years

were observed in our pediatric dermatology clinic to have

trichotillomania. In one child, there was co-existent alopecia

areata. All were referred to the child guidance clinic and they

all showed improvement with behavior therapy. A close liasion

between the dermatologist, psychiatrist and parents would go a

long way in preventing this alopecia.

Key words:

Children, trichotillomania.

Trichotillomania is

a disorder of compulsive hair pulling that results in

alopecia(1,2). While in dermatology, trichotillomania is

classified as a self-inflicted dermatosis, in psychiatry, it is

classified as an impulse-control disorder(3) along with conditions

such as compulsive gambling and kleptomania. Trichotillomania in

children is commonly associated with nail biting, thumb sucking,

anxiety and learning disability while adult patients show more

diverse psychopathology with depression, anxiety,

obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic attacks. Hair pulling and

plucking is commonest from the frontoparietal and temporal regions

of the scalp, often on the non-dominant side of the scalp although

occasionally the eyelash, eyebrow, pubic and hair on other body

sites may be involved(2). We describe three girls with

trichotillomania who presented with loss of hair over scalp and

other parts of the body; one of the patients had co-existing

alopecia areata.

Case Reports

Case 1:

A 4-year-old girl presented with loss of hair over the scalp of 6

months duration, since the time she had started going to school.

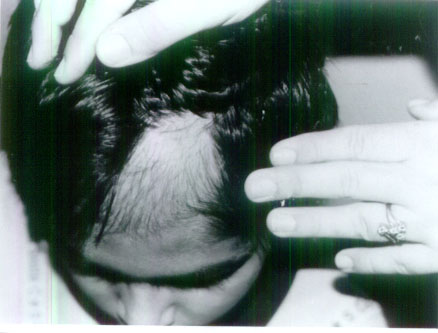

Examination revealed an irregular, coarse patch of hair loss over

the left frontal region of the scalp (Fig. 1). Short,

broken hairs of variable length were present, palpable as a

stubble. There was no evidence of scaling or inflammation, the

hair at the margin were not easily pluckable and the hair over the

rest of scalp was normal in texture and strength. There was no

history of loss of appetite, abdominal pain, diarrhea or

constipation. Examination of the mucous membranes, nails, oral

cavity and abdomen was normal. On questioning, the mother revealed

that this child was constantly fighting with her brother, was

obstinate and quick to take offense. Child was the youngest of

three siblings and pampered a lot by the grandparents. The mother

used to hit her often on undesirable behavior e.g. hair

pulling with her fingers when sitting idle and fighting. This

would often result in the child becoming angry and pulling out

more hair.

|

| Fig.1. A coarse patch of

loss of hair over left frontal area scalp with short broken

hairs. |

Case 2:

A 4-year-old girl presented with loss of hair over the vertex of

the scalp of 1-year duration. She had developed a small, bald

patch over the vertex of the scalp, which gradually increased in

size. There was no scaling but short exclamation mark hairs were

present which were confirmed on light microscopy of the hair; the

hair over the rest of the scalp was normal in texture and

strength. The rest of the cutaneous and systemic examination was

normal. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination of the hair was

negative. She was diagnosed as alopecia areata and was initially

treated with topical steroids for 4 weeks and later oral steroids

(prednisolone 10 mg OD) were given for 8 weeks. There was some

improvement in the form of hair regrowth but after a while the

baldness started extending on one side. On examination, coarse

irregular patches of hair loss with few short broken hair of

varying lengths palpable as a stubble were present on the left

temporal region of the scalp. No exclamation mark hair were seen.

The parents, on questioning, revealed that they had noticed the

child pulling out her hair from the sides of the scalp which was

not related to any activity. She was willful, frequently threw

temper tantrums, had the habit of thumb sucking and was the only

child of her parents.

Case 3:

A 6-year-old girl presented with loss of hair over the scalp of 4

years duration. The mother gave the history that the child

initially used to pluck out hair from the left parietal region of

the scalp, but since the last 6 months the child had started

pulling hair from the right parietal and temporal areas. Six

months back, the school of the child had been changed. She had the

habit of thumb sucking. The rest of the history, cutaneous and

systemic examination were similar as in case 1.

A potassium

hydroxide examination and light microscopic examination of the

hair was done in all cases which did not reveal any abnormalities.

A diagnosis of trichotillomania was considered in all three cases

though the second patient also had co-existing alopecia areata.

The parents were advised to shave the affected area and watch for

hair regrowth. The children were referred to the child guidance

clinic for behavior therapy where they were seen by a

psychiatrist, who also ruled out other psychiatric ailments. All

three girls had normal IQ. Parental counseling was dne for nature

of illness, to stop using physical punishment and to bring

consistency in discipline. The patients received several sessions

of play therapy, which were aimed at conflict identification, and

suggestion. Distraction was taught, to be used by parents.

Differential reinforcement was used where good behavior was

rewarded and rewards were withdrawn whenever there was undesirable

behavior. Along with these the first and the second child were

asked to make star charts and were rewarded with play sessions.

The first two patients benefited from therapy and their hair

showed re-growth on the shaved area and they stopped pulling out

the hair. The re-growing hair was of fairly uniform length though

thinner; and light microscopy revealed the hair ends to be

fractured. In the case of the third patient, after the counselling

and two sessions with the psychiatrist, the mother reported that

the child had stopped pulling hair from the scalp but had started

doing the same from the legs, as a consequence of which, patches

of hair loss were present over the legs. So, she was referred once

again to the child guidance clinic. However, subsequently the

child was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Trichotillomania is

a term coined by Hallopeau, a French dermatologist, in 1889(4). It

literally means a morbid craving to pull out hair. It may have a

multifaceted etiology, including alteration in brain metabolism, a

positive family history, a disturbed social setting and possibly

maternal deprivation(5). It occurs worldwide including in Indian

setup, and may prove to be a serious condition, if accompanied by

trichophagy and trichobezoar(6,7). Trichotillomania occurs more

than twice as frequently in females as in males in the adult age

groups, but below the age of 6 years boys outnumber girls by 3:2

ratio, although others have found the male to female ratio in

children to be 1:1(5). In clinical setting, the disorder

predominantly affects females(3), as also observed in the present

cases.

In psychiatry,

trichotillomania is classified under impulse control disorders(3).

Features of trichotillomania that fit this description include the

inability to resist urges to pull one’s hair which was present

in these cases and mounting tension before pulling and feeling of

relief afterwards which may not always be forthcoming especially

in a small child(8). However, in the present cases, the parents

had noticed the children pulling out the hair unconsciously or

deliberately. Moreover, the disturbance could not be accounted for

by another mental disorder or any dermatological condition and the

condition caused significant clinical distress, both of which were

other features, which supported the diagnosis. The child develops

the habit of twisting hair around his fingers and pulling it,

which is only partially conscious and may replace the habit of

thumb sucking(9) as observed in two patients. Other associated

clinical features include nail biting and temper tantrums. Hair

pulling and twirling is a normal aspect of behavior in children

and young adults and assumes clinical importance only when

significant alopecia develops(9).

It is usual for

trichotillomania to occur in a rather disturbed social setting.

Young girls may utilize this condition to avoid being sent to

school and to induce the parents to give in to their demands(9) as

noted in two of our patients. In early childhood, the factors

contributing to the emotional strain, which leads to

trichotillomania, are almost always found in a conflicting

mother-child relationship whereas, at the school-going age, it

usually results from the pressure on a child to achieve more or

sibling rivalry, which could be the case in the first patient.

From the psychodynamic point of view, hair may be regarded as a

‘transitional object’, which acts as a comforter to the child

who is distanced by the mother from the breast(9).

Alopecia areata and

trichotillomania present the most frequent causes of circumscribed

hair loss in children and can occur together in childhood(10), as

observed in the second patient. The connection between the two is

not very clear but it has been proposed that trichotillomania may

result from scratching at the site of alopecia areata that is

symptomatic with pruritus, initiating a habit-forming behavior, or

patients with a mental predisoposition may artificially prolong

the disfigurement as the hair on the bald patches of alopecia

areata regrows(10). Skin biopsy is useful for documenting the two

conditions (but was refused by the parents), although these can be

diagnosed easily by the dermatologist.

Early onset

trichotillomania, beginning before the age of six years is usually

self-limiting and responds to simple interventions involving

suggestion, reassurance and simple behavioral treatment

approaches(11), as was done in the present cases as well. In

children, the drug therapy which includes selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, neuroleptics and

lithium carbonate is rarely used(5). Trichotillomania may be

uncommon but must be thought of in cases where there is ambiguous

loss of hair in childhood with no apparent underlying cause and

where the scalp is normal or where almost no hair is lost by

combing or gentle pulling. Trichotillomania is best overcome by an

interdisciplinary approach to treatment and a liaison between the

dermatologists, psychiatrist and the parents is needed for the

effective management of this condition.

Contributors:

MB worked up the patients clinically, reviewed the literature and

drafted the manuscript. RS was the consultant-in-charge, provided

the concept, co-drafted the manuscript and revised it critically.

PA was the psychiatrist who treated the patients, co-drafted the

manuscript and revised it critically. AJK has overall critically

revised and approved of the manuscript in its final version. RS

shall act as the guarantor.

Funding:

None.

Competing interests:

None stated.

1. Cotterill JA,

Millard LG. Psychocutaneous Disorders. In: Champion RH,

Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, eds. Textbook of

Dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific

Publication 1998; pp 2785-2814.

2. Minichiello

WE, O’ Sullivan Rl, Osgood-Hynes D, Baer L. Trichotillomania:

clinical aspects and treatment strategies. Harv Rev Psychiatry

1994; 1: 336-344.

3. Christenson

GA, Crow SJ. The characterization and treatment of

trichotillomania. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57 (Suppl 8): 42-47.

4. Hallpeau H.

Alopecie par grattage (trichomanie ou trichotillomanie). Ann

Dermatol Syphiligr 1889; 10: 440-446.

5. Jefferson JW,

Greist JH. Trichotillomania - A Guide. 1st ed. Madisson

Institute of Medicine: Obsessie Compulsive Information Centre,

1998.

6. Sood AK, Behl

L, Kaushal RK, Sharma VK, Grover N. Childhood trichobezoar.

Indian J Pediatr 2000; 67: 390-391.

7. Sharma NL,

Sharma RC, Mahajan VK, Sharma RC, Chauhan D, Sharma AK.

Trichotillomania and trichophagia leading to trichobezoar. J

Dermatol 2000; 27: 24-26.

8. Burt VK.

Impulse-control disorders not elsewhere classified. In:

Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. Textbook of Psychiatry. 6th edn.

Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 1995; 1412-1415.

9. Cotteril JA.

Trichotillomania: a manipulative alopecia. Int J Dermatol 1993;

32: 182-183.

10. Trueb RM,

Cavegan B. Trichotillomania in connection with alopecia areata.

Cutis 1996; 58: 67-70.

11. International Classification

of Diseases. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural

disorders; Clinical description and diagnostic guidelines. 10th

edition. World Health Organization 1992.

|