Rupa Singh Piyush Gupta Kuldeep Singh Shekhar Koirala

From the Department of Pediatrics, B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Nepal.

Reprint requests: Dr. Rupa Singh, Department of

Pediatrics, B.P. Koirala Institute of Health

Sciences, Chapa Camp, Dharan, Nepal.

B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS), an autonomous Institute established

through an act of Nepalese Parliament

in 1993

is a major step towards making

Nepal self-reliant in the field of health care. The largest Nepal-India cooperation health project in Nepal so far, BPKIHS is envisaged as a nucleus of excellence in all aspects of health care deli very system at all levels and educating socially accountable physicians, nurses and allied health man- power. It will also cater to post graduate medical education and research so as to pro- vide specialists arid medical teachers to the country. Products of BPKIHS are expected to be a blend of academic excellence and conscientious commitment to the cause of positive

health(1).

BPKIHS is a residential university situated over a sprawling 699 acre campus with lush green vegetation at the foothill town of Dharan in Eastern Nepal. It has a functional 210 bedded hospital, which will be eventually upgraded to a 500 bed facility. Forty students are now being enrolled every' year to the MBBS programme after a rigorous selection. The faculty comprises of eminent medical specialists both from Nepal and India.

Development of a Need Based Curriculum

Need based education in Nepal stems from the fact that this country

is' one of the least developed and its health problems are

commensurate with that of low level of social development and poor economy(2). The founders of this Institute went through an evaluation of the existing medical systems, perceptions of the professionals and common people before deciding on the philosophy of the Institute. The broad objectives laid down for the institute were translated into action plan at an International Conference on Medical

Education held in December 1993 at

Dharan, participated in by eminent medical educationalists and, health services leaders from Nepal, India and WHO consultants. The MBBS curriculum of BPKIHS is ultimate outcome of this workshop and builds on

the strength of old by adding forceful and

validated new thoughts(3).

The principal objective of medical education is to produce doctors who possess clinical competence of a high order, have a sound community orientation, are proficient in communication skills and demonstrate attitudes befitting a health, professional. There are more than 1350 medical schools in the world ( over 135 in India). Except for a few of them, the rest follow subject based, teacher centered, theory laden, examination driven and specialization, oriented programs going on for decades without a review(4).

BPKIHS curriculum is designed to be need based, student centered, community oriented, throughly integrated, partially problem based and incorporates the organ system approach; a blend of idealism and realism in line with innovative medical education programs epitomized in the Edinburgh declaration of 1988(5,6). The curriculum encompasses all the six parameters outlined in the SPICES model and therefore differs markedly from the conventional model. Table I

depicts the contrasting approach between these two curriculum

strategies(7). While devising this curriculum, inspiration was also

drawn from the curriculum and programs of Care Western Reserve University, Cleveland, USA, School of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada (pioneer in use of interdisciplinary

problem based self directed learning), New Castle Medical School in Australia and Center of Medical Education, Dundee, Scotland.

TABLE I - Curriculum Strategies

|

SPICES model |

Conventional model |

| Student-centered |

Teacher centered |

| Problem-based |

Information gaterhing |

| Integrated |

Discipline based |

| Community based |

Hospital based |

| Elective |

Standard program |

| Systematic |

Opportunistic |

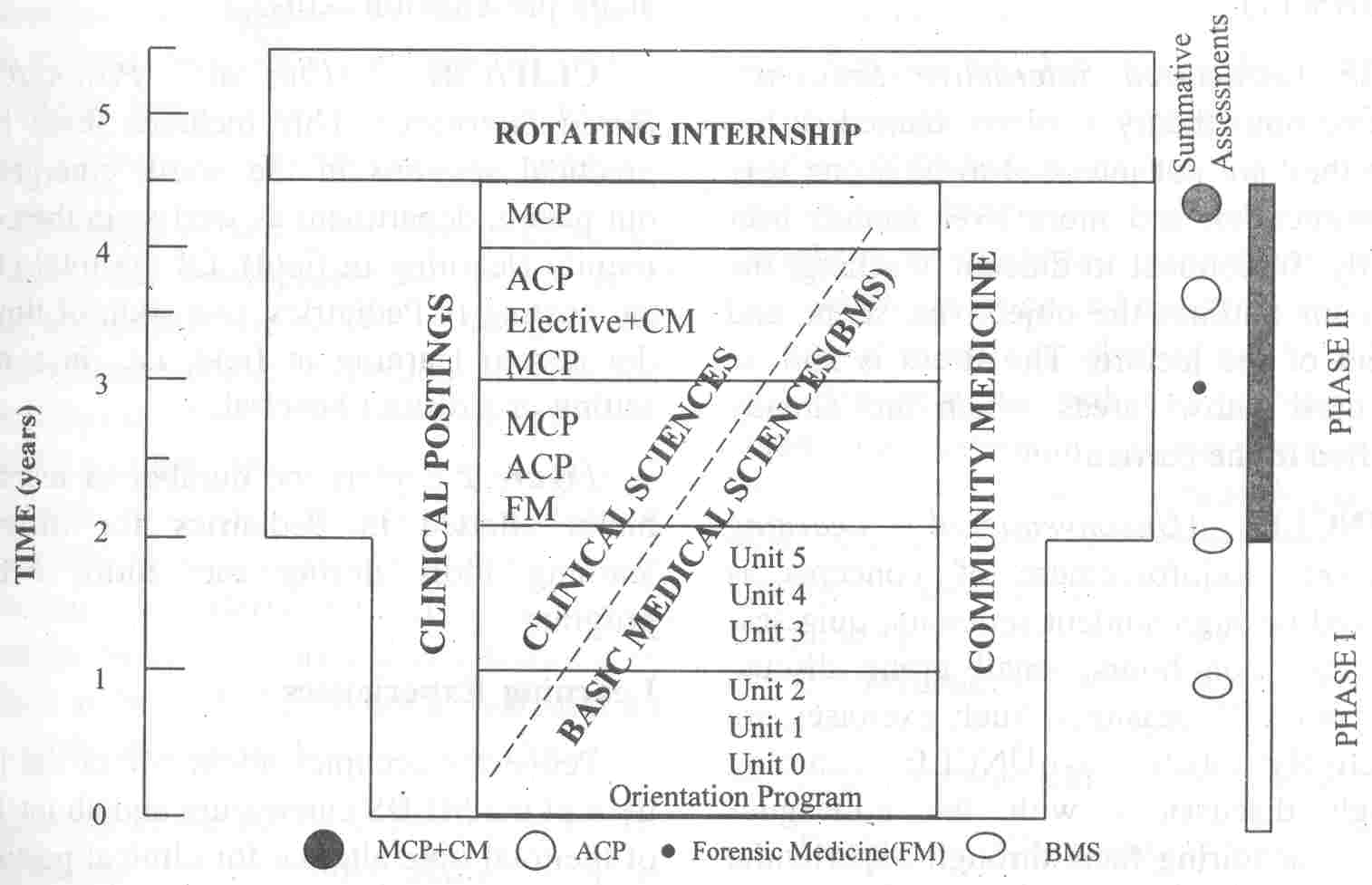

The MBBS curriculum of BPKIHS is committed to produce an undifferentiated generalist doctor capable of providing health services on his own to a large extent. During the Phase I of two years, the emphasis is on applied basic sciences along with community medicine and professional skills, while in Phase II spanning over next two and half years the stress is on clinical sciences with a high degree of integration between clinical and community medicine and applied basic

sciences. The curriculum incorporates early patient contact and emphasize on importance of study of community medicine and behavioral sciences from the very beginning. The focus remains on thorough integration aimed to be achieved at both horizontal and vertical levels throughout the entire course. Problem based Learning (PBL) exercises are organized at the beginning or end of an organ system to reinforce and recapitulate the basic concepts. The conceptual framework of the MBBS program isdiagramatically depicted in Fig. 1(5).

Pediatrics: A Separate Subject

Children under 14 years account for 42.4% of the total population of Nepal. In addition, Nepal has one of the poorest child health indicators with a Infant Mortality Rate of 79 per 1000 live births and under 5 mortality of 118 per thousand. Childhood malnutrition is rampant; underweight and stunting being prevalent in 49% and 64% children respectively. An estimated 90,000 under 5 deaths occur in Nepal every year predominantly of causes that are either preventable, easily treatable or manageable as a result of inadequate child health care system, inadequate

child care practices and child mal- nutrition(8-10). To improve the

existing preventive and promotive health care system for children, it

is thus imperative that the community physician has a proper training in common childhood ailments.

BPKIHS in its innovative MBBS curriculum has laid special emphasis on pediatric teaching by keeping it as a separate subject and more

importantly giving equal weightage to bring Pediatrics at par with

other major subjects including Medicine, Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology in terms of both time allotted for clinical posting as well as' marks allotted for final evaluation(5).

|

|

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework of the MBBS program at BPKIHS

Clinical Sciences (Figures in parenthesis indicate total duration of clinical posting in weeks)

MCP : Major Clinical Po stings [Medicine (12), Pediatrics (12), Surgery (12),

O&G

(12)]

CM : Community Medicine(6)

ACP : Allied Clinical Po stings: [Orthopedics (4), Emergency Medicine (8), Ophthalmology Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery (4), Anesthesiology (2), Psychiatry (2), Laboratory Medicine (2), Oral health (2), Dermatology (2), General Practice (4) and Radiodiagnosis (2)],

Elective: (10)

Basic Medical Sciences (BMS): Anatomy, Physiology, Biochemistry, Pathology, Pharmacology,

Microbiology. |

Pediatric MBBS curriculum at BPKIHS is need based with due consideration for

common local childhood problems, National Health Policy and programs.

It has emphasized on 'must know' areas by drawing up a core curriculum

and deleted the redundant to prevent factual overloading of students.

Common childhood problems like those concerned with growth and development, infectious diseases and neonatal care have been

given due importance to meet the real community needs.

Developmept of essential communication skills are also stressed besides possessing a sound

knowledge professional skills and medical ethics.

Learning Tools

The various instruments of learning in- cluded in the Pediatric curriculum

have been given titles that have originated in BPKIHS (11).

SIS (Structured Interactive Sessions): The one hour theory sessions, named so be- cause they are not intended to be a one way communication and more over sounds user friendly. In contrast to didactic teaching, the facilitator outlines the objectives, scope and content of the lecture. The stress is laid on the 'must know" areas which are already specified in the curriculum.

UNCLE (Unconventional Learning Exercise): Reinforcement of concepts is achieved through student seminars, quiz sessions,

question hours, small group discussions and PBL sessions. Such exercises are collectively labeled as. UNCLE. Learning through discussions with the colleagues helps in acquiring facts through experiential learning rather than through rote memory.

|

|

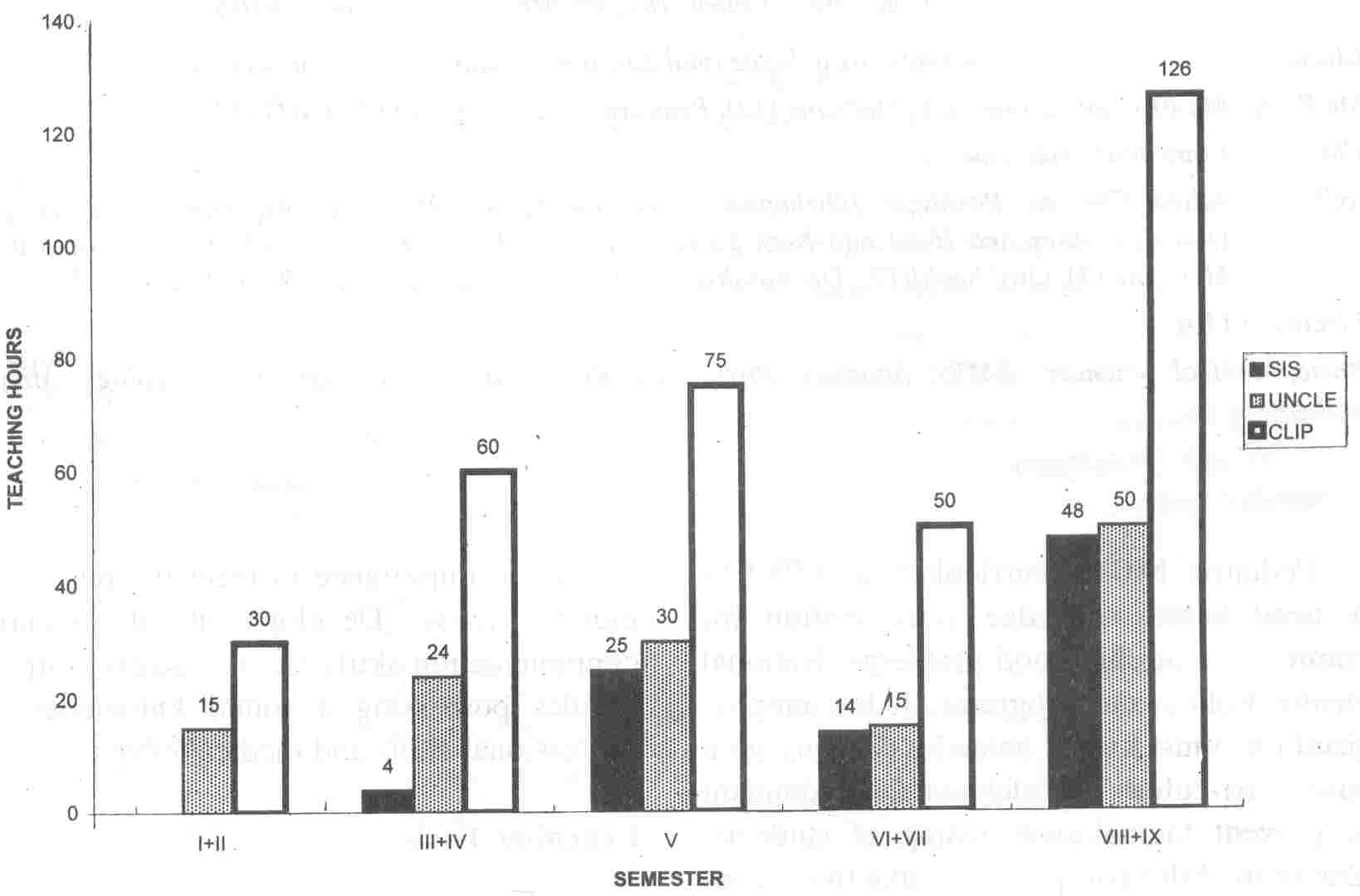

Fig. 2. Teaching hours allotted in Pediatrics for different teaming tools during MBBS (SIS: structured interactive session, UNCLE: unconventional learning exercise. CLIP: clinical

posting). |

This approach also helps the students to attain presentation skills.

CLIP/CBL (Clinical Posting/Case Based Learning): This

includes three hour practical sessions in the ward, emergency, out

patient department as well as in the community (learning in field). Of the total clinical posting in Pediatrics, one .sixth of time is devoted to learning in field, i.e., in a rural setting or a district hospital.

Figure 2 depicts the number of teaching hours allotted in Pediatrics for different learning tools during the' entire MBBS program.

Learning Experiences

Pediatrics occupies about 6% of the total time of the MBBS curriculum and about) 2% of the total time allotted for clinical postings. The teaching in Pediatrics starts right from

the beginning of Phase I of MBBS program and continues till the end of Phase II.

Teaching through lectures is restricted to a bare minimum while PBL and other unconventional learning experiences are encouraged.

Phase I (I-IV semester): Basics of normal growth and development and methods of their assessment are taught in 4 theory sessions of one hour each. Besides this, Pediatrics is involved in (i) Multisystem integrated student seminars that include topics on acute diarrheal, diseases, respiratory infections, rheumatic heart disease and common infections such as malaria and Kala-azar; and (ii)

Problem based multidisciplinary learning exercises at the end of each organ system (each one bf these exercise lasts for a week).

During Phase I clinical posting in Pediatrics, the basic art of history taking and physical

examination of different systems is learnt supervised by a tutor. The

students are encouraged to l1ake presentations and learn through discussions.

Phase II (V-IX semester): Theoretical concepts are learnt through SIS arranged in the organ system fashion. The theory topics specific for Pediatrics start from V semester and are continued in the VIII and IX semesters. Unconventional learning is carried out through small group discussions and problem based sessions assisted by a tutor. Students are exposed to their first block posting in Pediatrics in the V semester. During this five week posting, five sessions are allotted to learning in field in a rural setting or district hospital.

During VI and VII semesters, students are primarily posted in allied clinical subjects (Fig.

1). However, they do keep intact their touch with pediatric patients

by attending at least once a week clinical postings in the subject, named as Sharpen Your Clinical Skills

(SYCS) sessions. Students are also introduced to two entirely new subjects, i.e.,

General Practice and Emergency Medicine with clinical postings of 4 and 8 weeks, respectively.

Pediatrics is a major component of these two innovative subjects which

are taught in an integrated fashion and includes the general practice

and emergency problems of major as well as allied clinical subjects.

SIS are held for pediatric problems commonly encountered in general practice (acute respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, immunization, fever, behavioral and growth problems) and emergency (shock, poisoning, respiratory distress, congestive failure, anemia, convulsions, etc.). UNCLE continues through small group discussions, student seminars and problem solving sessions.

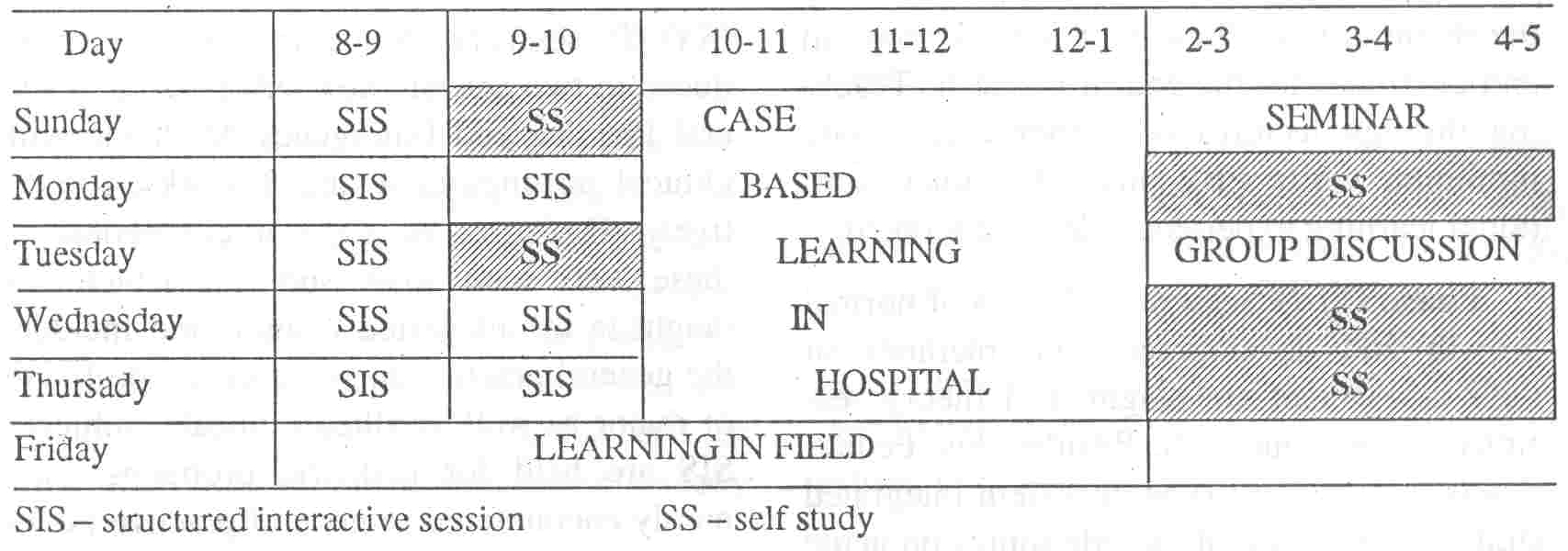

During the VIII semester, students again have a chance of coming back to Pediatrics during anyone of their five blocks of elective postings of two weeks each.' Final Clinical posting in Pediatrics in VIII and IX semester is scheduled for a period of total seven weeks. A typical weekly schedule for students during VIII and IX semester during Phase II is shown in Fig. 3. A large part .of the student's time is spent in independent study pursuing topics and learning issues either

derived from tutorial sessions or self generated. Some time is also

spent interacting with faculty members who act as important resources for learning.

|

|

Fig 3. Sample schedule of student week during Phase II, Semester VIII and IX of the BPKIHS curriclum. |

At the end of every organ system, the students are encouraged to evaluate the

teaching activities and suggest improvements by tilling up a structured questionnaire. Constructive criticism is usually associated with improvements in the teaching methodology.

Assessment

The weightage given to Pediatrics amount to 20% of the total marks in Final

MBBS examination at par with General Medicine, General Surgery, Obstetrics and

Gynecology and Community Medicine. The students go through both formative and summative evaluation.

Internal Assessment: The students are evaluated at the completion of each semester. Students of first four semesters are assessed only for their clinical skills through anintegrated

practical examination that includes all major subjects. Separate

theory and practical examinations for Pediatrics are held following the V, VIII and IX semesters. Theory and practical examinations in General Practice and Emergency Medicine are held at the end of VI and VII semester where pediatrics is integrated

with other major and allied subjects. From V semester onwards, constant evaluation regarding the student's ability to take history, perform clinical examination and derive useful conclusions forms a part of clinical postings. Students are also assessed during the unconventional learning exercises being held throughout their curriculum.

The internal assessment therefore continues throughout and results are opened to enable students to improve upon their performance. Marks earned contribute to 20% of the total score for final summative examination,

equally divided between theory and practical. This is in accordance

with the recently suggested guidelines(12).

Summative Evaluation: The final

.

summative examination will be conducted at the 'end of IX semester consisting of two theory papers of 160 marks each [Paper 1- Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) and Short Answer Questions (SAQ); Paper-II-Modified Essay Questions (MEQ)]

and practical examination of 320 marks. Practical will include a clinical examination in form of OSCE, structured short case presentation (80% weightage) and viva-voce (20% marks of total practical marks).

Assessment Tools

Every attempt is made to reduce subjectivity and to bring in more objectivity both in theory and practical components, as suggested recently(13). The students are given a precise task that is interpreted identically by various observers. The questions are framed clearly and according to the learning objectives already specified.

Assessment o/Knowledge (Theory examinations): Theory papers consist of three types of questions, i.e., multiple choice

(MCQ), short answer type (SAQ) and modified essay questions (MEQ). The correct

answer and the scoring pattern is predetermined for each type of question. MCQs could be of single answer, multiple response or reason assertion type. There is no negative marking.

Practical examination is aimed to be completely objectivized, reliable, valid and student centered. These are designed to test not only the knowledge but psychomotor skills, communications skills, attitude, etc. by means of objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) and problem solving exercises (PSE). In addition, objectivized short case presentations are also included in the final summative examination. .While' OSCE permits objective evaluation of clinical skills within a short time, the analyzing and synthesizing ability of the student is best evaluated using clinical case presentations(l4). Viva voce examinations are also standardized up to a major extent to minimize the chance factor.

In order to pass, a student has to secure a minimum of 50% and 60% of the total marks in theory and practical separately.

Epilogue

Pediatrics as a separate and major subject is the need of the hour

giving due consideration to poor child health status of the country

and need to train the health staff in management of common child health problems and delivery care. The BPKIHS curriculum 'has a provision for (i) constant evaluation of teaching learning methodology, quality of teaching and learning tools and resources; and (ii) imparting training to the teachers to practice this new system of medical education.

As the new curriculum is currently being introduced and no graduates have yet been

produced under this program, it is premature to examine the impact of

these developments in the health services sector. However, the staff

as well as the students are showing very positive attitudes and there

is enthusiasm among both the teachers and students to develop problem solving exercises and self directed

learning skills. The curriculum if proved to be effective and useful

may also' serve as an example to India where the MCI has already

stressed upon a need based curriculum(15).

The aim is that students should learn

well, find learning a pleasure, want to learn more and use efficiently what they learn to serve the children of Nepal(11). It is hoped that this thoroughly contemporary curriculum

with a futuristic outlook will stand the test of time and serve as a

model for medical schools of the future to adopt or adapt.

|

1.

Koirala S, Kumar N, Upadhyay M. Institutional goals and philosophy of B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Ghopa, Dharan. J Inst Med 1994; 16: 1-4.

2.

Mattock NM, Abeykoon P. The Institute of Medicine. Tribhuvan University, Nepal; Designing a Country Specific Prognimme. Innovative Programmes of Medical Education in South East Asia, WHO SEARO, New Delhi. 1993; pp 29-40.

3.

Medical Education for Twenty First Century: A brief report. Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Education, Dharan, 12-14 December 1993, J Inst Med 1994; 16: 94-101.

4.

Paul YK. Innovative programmes of Medical education I. Case studies. Indian J Pediatr

1993; 60: 759-768.

5.

The first version of the MBBS curriculum of BP. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Ghopa, Dharan, Nepal 1996.

6. The Edinburgh Declaration: World Conference on Medical

Education of the World Federation on Medical Education. Med Edu 1988: 22: 481-482.

7.

Harden RM, Sowden S, Dunn WR. Educational 'strategies in curriculum development:. The SPICES model. Med Edu 1984; 18: 284- 297.

8. Population Monographs of Nepal. Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commission, HMG, Kathmandu, Nepal 1995.

9. Nepal Family Health Survey Report. Family Health Division, Department of

Health Services, Ministry of Health, HMO, Nepal, 1997;

P 102.

10.

Nepal Multiple Indicator Surveillance: Health and Nutrition. National Planning Commission Secretariat: HMG, Nepal and UNICEF,

Nepal-Cycle I, January-March 1995; pp 35- 38.

11.

Bijlani R. The MBBS Programme of BPKIHS. Vision. BPKIHS, Dharan 1995; pp 8-10.

12.

Singh T, Singh D, Natu MV. Suggested model for internal assessment as per MCI Guidelines on Graduate Medical Education, 1997. Indian Pediatr 1998; 35: 345-347.

13.

Singh T, Natu MV. Examination reforms. at the grassroots: Teacher as the change agent. Indian Pediatr 1997; 34: 1015-1019.

14.

Verma M, Singh T. Experience with OSCE as a tool for formative evaluation in Pediatrics. Indian Pediatr 1993; 30: 699-701.

15.

Medical Council of India. Guidelines on Graduate Medical Education. New Delhi, Medical Council of

India 1997.

|