|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58: 184 -186 |

|

Hepatic Visceral Larva Migrans Causing

Hepatic Artery Pseudo-Aneurysm

|

|

Ritu,1 Kumble S Madhusudhan2 and

Rohan Malik3*

Departments of 1Pediatrics, 2Radiodiagnosis,

and 3Hepatology and Clinical Nutrition,

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Email:

[email protected]

|

|

Visceral Larva Migrans refers to migration of second

stage nematode larvae through human viscera most commonly the liver and

lungs. This entity usually presents with fever, abdominal pain,

hepatomegaly and respiratory symptoms. Here we describe hepatic visceral

larva migrans causing hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm and presenting with

upper gastro-intestinal bleeding and its management.

Parasitic infections of liver are commonly

encountered in clinical practice and can have myriad presentations

posing a clinical diagnostic challenge. Hepatic visceral larva migrans

(VLM) is one such entity presenting with prolonged fever and liver

involvement especially in areas endemic for the parasite. Hepatic artery

pseudoaneurysm is a complication described mostly with traumatic liver

injury and post-surgery [1]. We describe this complication secondary to

hepatic VLM and its successful management.

A 12-year-old girl presented with high grade fever,

jaundice and right upper abdominal pain with progressive abdominal

distension associated with weight loss for four months and a history of

recurrent black tarry stools requiring blood transfusions. She was

resident of a rural area and her family of seven lived in an overcrowded

house, belonged to lower socioeconomic status with poor hygiene

practices, consumed vegetarian diet and had exposure to pet animals in

neighborhood. On examination she was underweight (BMI 12.5 kg/m2),

febrile and tachypneic, had severe pallor with pedal edema and no skin

lesions. Systemic examination revealed firm tender hepatomegaly (liver

span:17 cm) without ascites or splenomegaly and crepitations on right

side of chest. Ophthalmoscopic examination was unremarkable.

Investi-gations revealed anemia (hemoglobin 5.7g/dL), and leukocytosis

(16×103/L) with eosinophilia (1.4×103/L). Liver function tests were

alanine aminotransferase 23 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase 19 U/L,

alkaline phosphatase 590 U/L, total bilirubin 1.5 mg/dL with direct

fraction 1.2 mg/dL, serum albumin 1.9 g/dL with albumin:globulin ratio

of 0.4. As the child was sick at arrival, she was started on broad

spectrum antimicrobials and supportive treatment (blood transfusion and

albumin). Ultrasonography showed hepatomegaly with diffuse hypoechoic

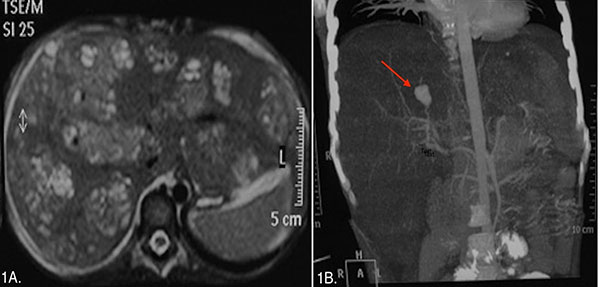

cystic lesions in both lobes of the liver. MRI abdomen showed lesions in

the liver appearing hypointense on T1-weighted and hyperintense on

T2-weighted images (Fig.1a) with mildly dilated common bile duct

and normal intrahepatic biliary radicles. Dual phase CT scan of abdomen

revealed multiple discrete and confluent hypodense lesions in both lobes

of liver along with a 1.5 cm pseudoaneurysm (arrow) arising from the

posterior branch of the right hepatic artery (Fig.1b). Based on

clinical and radiological findings, a differential diagnosis of visceral

larva migrans, cat scratch disease, Fascioliasis, disseminated

tuberculosis and invasive candi-diasis with underlying immunodeficiency

along with pseudo-aneurysm with suspected hemobilia was kept. The

patient underwent digital subtraction angiography (DSA) and successful

embolization of the pseudoaneurysm with n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue.

Subsequent investigations revealed normal stool examination and negative

Toxocara IgG serology, Echinococcus IgG serology, procalcitonin, Mantoux

test, gastric aspirate genexpert for Tuberculosis, and HIV serology.

Bacterial and fungal blood culture was sterile and upper GI endoscopy

was normal. Percutaneous liver biopsy demons-trated ill-defined

eosinophilic granulomas suggesting parasitic infiltration. Special

stains and tissue culture was negative for acid fast bacilli (AFB),

Bartonella and fungal elements. Based on clinical, radiological and

histopathological findings, diagnosis of visceral larva migrans was made

and child was started on albendazole (10mg/kg/day), diethylcarbamazine

(4mg/kg/day) and oral steroids (1mg/kg/day) in 3 cycles of 3 weeks each

with gradual tapering of steroids over next one month. Follow up imaging

at six months showed resolution of hepatic lesions.

|

|

Fig. 1 (a) Axial T2 weighted MR image

shows multiple conglomerate heterogeneous lesions in both lobes

of liver, (b) Coronal CT angiography image shows a

pseudoaneurysm (arrow) arising from the posterior branch of

right hepatic artery.

|

Visceral larva migrans (VLM) refers to migration of

second stage nematode larvae through human viscera most commonly liver

and lungs. The etiological agents include Toxocaracanis, Toxocaracati,

Baylisascarisprocyonis, Cappilaria hepatica, and Ascarissuum

[2]. Humans are accidental hosts and acquire infection by ingestion of

food contaminated with infective eggs. The clinical manifestations are

fever, hepatomegaly, weight loss and respiratory symptoms mimicking

asthma. An IgG ELISA based on 30 kDa recombinant Toxocara excretory–secretory

antigen has 92% sensitivity and 89% specificity [3]. Features suggestive

of VLM on CT are presence of multiple confluent peripheral and

periportal ill-defined hypodense, oval or elon-gated nodular lesions

scattered throughout liver parenchyma with peripheral rim enhancement

and MRI shows T2 hyperintense/T1 hypointense lesions with restriction on

diffusion weighted sequences [4]. Confirmation is by histo-pathological

examination which shows presence of eosino-philic granuloma, palisading

histiocytes and very rarely larva may be visualized. The slow migration

of larva through the tissue incites a host inflammatory response along

with eosinophilic infiltration and destruction of liver parenchyma. The

cytotoxic eosinophil derived proteins may damage the endothelium causing

vascular complications [5]. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm, a rare

complication has not been previously described with VLM. Pseudoaneurysm

develops due to the erosion of the eosinophilic abscesses into the

hepatic artery. Rupture of the aneurysm results in hemobilia and the

patients may present with hematemesis or melena or both. In cases of

rupture of the aneurysm, early intervention by angio-embolisation of

feeding artery should be considered. The embolizing agents used include

coils, n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue and thrombin [1]. Medical therapy

includes diethyl-carbamazine, mebendazole or albendazole for 2-3 weeks.

Steroids are indicated in cases of ocular and neurological toxo-cariasis

and in acute inflammatory manifestations of VLM [6].

We conclude that hepatic VLM can be a rare cause of

hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm resulting in upper gastro-intestinal

bleeding. Early recognition and comprehensive management is of utmost

importance.

REFERENCES

1. Nagaraja R, Govindasamy M, Varma V,et al. Hepatic

artery pseudoaneurysms: A single-center experience. Ann Vasc Surg.

2013;27:743-9.

2. Beaver PC, Snyder CH, Carrera GM, Dent JH,

Lafferty JW. Chronic eosinophilia due to visceral larva migrans: Report

of three cases. Pediatrics. 1952;9:7-19.

3. Norhaida A, Suharni M, LizaSharmini AT, Tuda J,

Rahmah N. rTES-30USM: Cloning via assembly PCR, expression, and

evaluation of usefulness in the detection of toxocariasis.Ann Trop Med

Parasitol. 2008;102:151-60.

4. Laroia ST, Rastogi A, Bihari C, Bhadoria AS, Sarin

SK. Hepatic visceral larva migrans, a resilient entity on imaging:

Experience from a tertiary liver center. Trop Parasitol. 2016;6:56-68.

5. Young JD, Peterson CG, Venge P, Cohn ZA.

Mechanisms of membrane damage mediated by human eosinophilic cationic

protein. Nature. 1986;321:613-6.

6. Magnaval JF, Glickman LT. Management and treatment options for

human toxocariasis. In: Holland CV, Smith HV, editors. Toxocara:

The Enigmatic Parasite. CABI Publishing; 2006.p.113-26.

|

|

|

|

|