|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58: 153-161 |

|

Indian Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines for

Pediatric Skin Care

|

|

R Madhu, 1

Vijayabhaskar Chandran,1 V

Anandan,2 K Nedunchelian,3

S Thangavelu,4 Santosh T

Soans,5 Digant D Shastri,6

Bakul Jayant Parekh,7 R

Remesh Kumar8 and GV

Basavaraja9

From 1Department of 1Dermatology, Venereology and

Leprosy, Madras Medical College, Chennai, Tamil Nadu; 2Department of

Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, Govt Stanley Medical College,

Chennai, Tamil Nadu, 3Research and Academics and 4Department of Pediatrics, Mehta Multispeciality Hospitals, Chetpet, Chennai, Tamil

Nadu; 5AJ Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Mangalore,

Karnataka; 6Killol Children Hospital, Surat, Gujarat; 7Bakul Parekh

Children Hospital and Multispeciality tertiary care centre, Mumbai,

Maharashtra; 8Apollo Adlux Hospital, Cochin, Kerala; and 9Indira Gandhi

Institute of Child Health, Bangalore, Karnataka; India.

Correspondence to: Dr C Vijayabhaskar, No 4, Gandhi

Street, SS Nagar Extension, Thirumullaivoyal, Chennai 600 062,

Tamil Nadu, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

|

Objective :

To develop standard recommendations for skin care in neonates,

infants and children to aid the pediatrician to provide quality

skin care to infants and children. Justification: Though

skin is the largest organ in the body with vital functions, skin

care in children especially in newborns and infants, is not

given the due attention that is required. There is a need for

evidence-based recommendations for the care of skin of newborn

babies and infants in India. Process: A committee was

formed under the auspices of Indian Academy of Pediatrics in

August, 2018 for preparing guidelines on pediatric skin care.

Three meetings were held during which we reviewed the existing

guidelines/ recommendations/review articles and held detailed

discussions, to arrive at recommendations that will help to fill

up the knowledge gaps in current practice in India. The initial

draft of the manuscript based on the available evidence and

experience, was sent to all members for their inputs, after

which it was finalized. Recommendations: Vernix caseosa

should not be removed. First bath should be delayed until 24

hours after birth, but not before 6 hours, if it is not

practically possible to delay owing to cultural reasons.

Duration of bath should not exceed 5-10 minutes. Liquid cleanser

with acidic or neutral pH is preferred, as it will not affect

the skin barrier function or the acid mantle. Cord stump must be

kept clean without any application. Diaper area should be kept

clean and dry with frequent change of diapers. Application of

emollient in newborns born in families with high risk of atopy

tends to reduce the risk of developing atopic dermatitis. Oil

massage has multiple benefits and is recommended. Massage with

sunflower oil, coconut oil or mineral oil are preferred over

vegetable oils such as olive oil and mustard oil, which have

been found to be detrimental to barrier function.

Keywords: Cleanser, Emollients,

Infant, Massage, Newborn.

|

|

Skin is the largest organ in

the human body with

vital functions such as barrier integrity,

thermoregulation, immunological function,

protection from invasion of microbes and ultraviolet rays [1].The skin

of a newborn or an infant is different from the adult skin. Skin of the

term newborn is 40-60 times thinner, less hydrated and has reduced

natural moisturizing factor (NMF) compared to the adult skin. The skin

of a preterm baby is thinner than that of a term baby and is vulnerable

to impaired thermo-regulation, increased skin permeability, increased

transepidermal water loss (TEWL), dehydration, predisposition to trauma

and increased percutaneous absorption of toxins. The fragile and

delicate nature of the skin of the neonate calls for special care in

cleansing. It has been observed that skin of the newborn undergoes

various structural and functional changes from birth to first five years

of life [2,3]. About 30% of children who attend the pediatric

out-patient departments present with dermatological disorders, which

makes it essential to prioritize skin health from the very beginning

[4]. Skin care in newborn or a child is not given the due attention that

is required, and in addition, in India, there are varied community and

culture-based practices that can adversely affect the healthy skin in

babies [5]. Hence, there is an urgent need for formulation of standard

recommendations for skin care of newborns and infants in India based on

the available literature.

PROCESS

To accomplish the goal of preparing guidelines on

pediatric skin care, a committee comprising of pediatricians and

dermatologists with experience in pediatric dermatology (Annexure I)

was formed under the auspices of Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) in

August, 2018. We performed an a literature search across multiple search

engines, namely Pubmed, MEDLINE, Cochrane and Google Scholar for the

terms, "newborn/ preterm/infant skin care", "first bath", "WHO

guidelines", "recommendations", "cord care", "nappy care", "cleanser",

"emollients", "massage." Search was limited till September, 2019. We did

a systematic review of the evidence available on skin care for babies in

the various headings such as bathing, cleansing, care of the umbilical

cord, nappy care, care of hair, cleansers, oils used for baby massage,

atopic dermatitis and dry skin. Three meetings were held, during which

we reviewed the existing guidelines/recommendations and review articles,

and held discussions, with regard to skin care practices in neonates,

infants and children, to arrive at recommendations that will help to

fill up the knowledge gaps in current practice in India. The first

meeting was held in Mumbai on 5 August, 2018 and the two subsequent

meetings were held at Chennai on 12 May, 2019 and 20 October, 2019. An

initial draft was prepared based on the available evidence and

experience, and then sent to all the other members for their inputs,

after which, the final recommendations were drafted.

GUIDELINES

Newborn Skin Care

Care of the skin of newborn babies encompasses

assessment of the skin, identification of the risk factors that will

affect the barrier function and routine care of skin.

Assessment of the skin of the neonate: During the

first examination of the newborn, it is essential to do a head to foot

examination of the skin. Various parameters to be observed are dryness,

scaling, erythema, colour, texture and physiological changes. Neonatal

skin condition score (NSCS) based on the score (1 to 3) given to the

condition of neonate’s skin related to dryness, erythema, and break

down/excoriation is useful for daily evaluation of newborn skin. Perfect

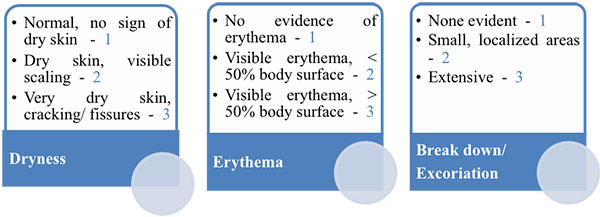

score is considered to be 3, while worst score is 9 (Fig. 1) [6].

|

|

Fig. 1 Neonatal skin condition score.

|

Identification of risk factors that will affect the

barrier function: Epidermal barrier function will be affected due to

immaturity of the skin, phototherapy, iatrogenic injuries, extensive

epidermolysis bullosa, septicaemia and environmental temperature.

Treatment related risk factors may occur due to antiseptics, adhesives

and vehicles in topical medications. Term babies with either

physiological or pathological jaundice on phototherapy and preterm

babies in incubator are susceptible to increased transepidermal water

loss (TEWL).

Routine care of skin in term and preterm

Ideal care of skin of newborn comprises of gentle

cleansing, protection of barrier function, prevention of dryness of

skin, avoidance of maceration in the body folds and exposure to toxins,

prevention of trauma and promotion of normal development of skin.

Skin to skin care

WHO recommends that soon after birth, baby is placed

on the abdomen of the mother before the cord is cut or over the chest

after the cord is cut, after which entire skin and hair is wiped with a

dry warm cloth. It is strongly recommended that the baby dressed only in

a diaper (maximises the skin to skin contact between the baby and the

mother), be left on the mother’s chest with both of them being covered

with pre-warmed blankets, for at least 1 hour after birth, as this will

help to promote breast feeding and prevent hypothermia. WHO strongly

recommends skin-to-skin care (SSC) for all mothers and newborns without

complications, irrespective of the mode of delivery immediately after

birth [7]. (Strong recommendation; Level of evidence VII). If the

mother is unable to keep the baby in skin to skin contact due to

complications, then the baby should be well wrapped in a warm, soft dry

cloth. Head of the baby should be well covered with a dry cloth to

minimize the heat loss.

Vernix caseosa

Vernix caseosa is a natural cleanser and moisturiser

known for its anti-infective, antioxidant and wound-healing properties.

Development of acid mantle is facilitated by vernix caseosa, which also

supports the normal bacterial colonization [8,9]. WHO and the European

round Table meeting recommend that vernix caseosa should not be removed

because of the various beneficial functions [10-12] (Strong

recommendation; Level of evidence VII). Vigorous rubbing of the baby

should be avoided. If the baby’s skin is stained with blood or meconium,

wet cloth should be used to wipe followed by a dry cloth.

First Bath of the Newborn

It is a well-known fact that bathing in newborn can

lead to hypothermia, increased demand of oxygen, unstable vital signs

and disruption of behavior. WHO recommends that the first bath should be

delayed until 24 hours after birth but not before 6 hours, if it is not

practically possible to delay owing to cultural reasons. But while

bathing a baby after 6 hours of life, one must ensure that the baby is

normothermic with a stable cardiorespiratory status [10-14]. (Strong

recommendation; Level of evidence VII). This holds good for a term

baby weighing more than 2.5 kgs. Delayed bathing promotes successful

initiation of breast feeding, and facilitates bonding and skin to skin

care [15]. Bath should always be given in a warm room and the

temperature of bath water should be between 37 0C

and 37.50C [11]. Temperature

of the water should be checked by the health worker or caregiver by

immersing their hand. Duration of bath should not exceed 5-10 minutes as

an over hydrated skin is fragile with increased threshold for injury

[11] (Strong recommendation; Level of evidence VII).

If choosing to give a tub bath, depth of the water

should be 5 cm, up to the hip of the baby. As bath tub and bath toys are

potential sources of infection, they must always be disinfected [11]. It

would be ideal for the health workers to use gloves while giving the

first bath [11]. In those babies born to mothers infected by hepatitis B

and/or HIV, bath should be given at the earliest when the baby is

physiologically stable, with stringent aseptic precautions [16,17].

It will be ideal to use a synthetic detergent

(syndet) rather than a soap to cleanse the baby as the latter tends to

damage the epidermal barrier. It has been observed that it takes about

an hour for the regeneration of skin pH after use of soaps. Syndet

liquid cleansers are preferred over syndet bars. Liquid cleansers with

acidic or neutral pH (appropriate blend of ionic, non-ionic and

amphoteric surfactants) do not affect the skin barrier function or the

acid mantle and hence recommended. AWHONN (Association for Women’s

Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses) neonatal skin care guidelines

recommends the use of minimal amount of pH neutral or slightly acidic

cleanser [17]. (Strong recommendation; Level of evidence VII). In

case of cost constraint, a mild soap with low alkaline pH may be

minimally used; although, soaps are best avoided in neonates [11,18].

Routine Bathing in Neonates, Infants and Children

Routine bathing of newborn and infants is mainly need

based and dependent on the regional, cultural and climatic conditions.

Daily bath not exceeding 15 minutes is preferable, except during winter

or in hilly regions, wherein bath may be given twice or thrice in a week

or as per the local culture [11]. After bathing, baby should be dried

from head to foot using a dry warm towel. Use of bubble baths and bath

additives should be avoided as these may increase the skin pH and cause

irritation.

Care of the Diaper Area

Diaper area exposed to excessive hydration,

maceration, occlusion and friction has an increased pH due to the action

of fecal ureases on urea. This increase in pH potentiates the action of

fecal enzymes, which are highly irritant to the skin. Hence, diaper area

should be always kept clean and dry [19]. Moistened cloth or cotton ball

soaked in lukewarm water could be used to clean the area after

defecation [20] (Strong recommendation; Level of evidence VII).

Dry soft cloth/towel can be used to pat dry the skin. Cloth should not

be dragged on the skin during removal of faeces or urine or while

drying. Only a mild cleanser with slightly acidic to neutral pH that

will not disturb the barrier function should be used in the perineal

area [11,18,21,22].

Diapers should be changed frequently in order to

prevent diaper dermatitis [11,17]. (Strong recommendation; Level of

evidence I). Duration could vary from every 2 hours in neonates to

every 3-4 hours in infants. Cloth napkins are preferable. These are to

be washed in warm water and dried in sunlight. Frequent exposure of the

nappy area to air would be beneficial [18,22]. If frequent change of

napkins is not possible, application of mineral oil to the skin over the

diaper area will act as a barrier [18,22]. Baby wipes that are mild on

the infant skin may be used [23]. (Strong recommendation; Level of

evidence III). Wipes should be free of fragrance and alcohol. If

disposable diapers have to be used, superabsorbent gel diapers may be

used. Application of barrier creams containing zinc oxide, dimethicone

and petrolatum-based preparation at each change of diaper will be

beneficial in babies with diaper dermatitis [24] (Strong

recommendation; Level of evidence I).

Care of the Umbilical Cord

Umbilical cord should be cleaned with lukewarm water

and kept dry and clean. Care taker’s hands should be washed before and

after cord care. If the stump is soiled, it should be washed with water

and syndet /mild soap and dried thoroughly with soft, clean cloth. WHO

recommends that nothing should be applied on the cord stump [10,12] (Strong

recommendation; Level of evidence VII). Diaper should be cladded

below the stump. No bandage should be applied on the stump [10,12].

Care of the Scalp

First hair wash in a newborn baby may be given after

the cord falls. Cradle cap of the scalp is the common problem in newborn

babies. Application of mineral oil to the crust and removal after 2 to 3

hours will be helpful. Baby shampoos which are free from fragrance could

be used. They should not cause irritation to the eyes [18,22]. Hair wash

can be given once or twice a week or as and when required in case of

soiling [18,25]. In case of children, hair wash can be given twice a

week using a mild shampoo.

Care of Nails

Nails should be cut and kept short [18,26].

Use of Baby Talcum Powders

Routine use of powders is not advocated in neonates

and young infants. In the case of infants, if desired, mother should be

advised to smear the powder on the hands and then gently apply on the

skin of the baby. Puffs should not be used as it may result in

accidental inhalation of powder [18,25]. Powder should not be applied in

the groins, neck, arm and leg folds.

Care of Skin of Preterm Baby

Preterm baby should be kept in a warm environment.

Gentle and minimal handling of the preterm babies would be ideal. Hand

hygiene measures are to be followed strictly by the

mother/caregiver/healthcare workers. Kangaroo mother care is recommended

for the routine care of preterm and low birth weight newborns weighing

2000 g or less at birth, as soon as the neonates are clinically stable

[12] (Strong recommendation; Level of evidence VII).

Tub-bathing which results in less heat loss, is

recommended as a safer and comfortable option than sponge bathing in

healthy, late preterm infants with gestational age (GA) between 34-36

weeks [27,28]. In a randomized clinical trial (RCT) [29], swaddle

immersion bathing method was found to maintain temperature and reduce

stress in preterm babies with GA between 30-36 weeks from 7-30 days of

postnatal age compared to conventional bathing, and hence was concluded

as an appropriate and safe bathing method for preterm and ill infants in

NICUs [29]. Swaddled bathing was found to be more effective at

maintaining body temperature, oxygen saturation levels and heart rate

compared to tub bathing. AWHONN recommends the use of only warm water

without use of cleansers, during the first week of life in infants less

than 32 weeks of gestation [17]. UK Neonatal skin care guidelines state

that babies less than 28 weeks of gestation should not be bathed and

instead recommends the use of sterile pre-warmed water to pat dry the

skin [30]. Sponge bathing given in stable preterm neonates resulted in a

transient drop of temperature at 15 minutes, but not to the extent of

causing hypothermia and subsequently temperature began to rise by 30

minutes and normalized by 1 hour post-bath. Hence, it appears to be a

safe method of routine cleansing of stable preterm babies [31]. A RCT

[32] documented that bathing preterm neonates every 4 days decreases the

risk of temperature instability [32].

To summarize, preterm babies with GA less than 28

weeks should not be bathed, and in case of soiling, sterile pre-warmed

water could be used to cleanse with gentle patting of the skin to dry

[30] (Strong recommendation; Level of evidence IV). In India,

sponge bathing is the most common method, currently in vogue, to cleanse

babies with GA between 28-36 weeks. However, as the comparison studies

between sponge bathing and swaddle immersion bathing, have documented

that the latter method is more efficacious in thermoregulation and

maintenance of oxygen saturation, swaddle immersion bathing could be

adopted, with the training of nursing staff [29] (Strong recommendation;

Level of evidence II). As there is paucity of Indian literature in this

area, the need for more research is highlighted.

Preterm babies are more vulnerable to develop

percutaneous toxicity because of the thin skin and larger body surface

area. Hence stringent care should be taken while using topical

antiseptics in these babies. Alcohol containing solutions have been

shown to cause skin burns and hence best avoided in preterm babies. 2%

Chlorhexidine is a safer alternative topical antiseptic agent used in

newborn units. Use of gentle medical adhesives to secure intravenous

cannulas is to be practiced because epidermal stripping secondary to

removal of adhesive dressing is the main cause of skin injury in preterm

babies. Adhesive should be loosened with mineral oil or petrolatum based

emollient and removed gently avoiding the use of adhesive removers.

Position of the baby must be frequently changed. Gentle application of

appropriately selected emollients will help to decrease the TEWL and

maintain the barrier function [11].

Ideal Cleanser

An ideal cleanser is one that is mild and fragrance

free with neutral or acidic pH and does not irritate the skin or eyes.

It should not affect the acid mantle of the skin surface, remove the

lipids/ natural moisturizing factor (NMF) or disrupt the barrier

function [25]. Soapless liquid cleansers appropriately formulated for

use in babies could be preferred by virtue of the maintenance of barrier

function [11,33]. In children with normal skin, mild soaps are to be

used. Syndets are preferred in children with skin disorders that disrupt

the barrier function such as atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis, eczema,

psoriasis etc.

Shampoos

They are soapless, and consist of principal

surfactant for detergent and foaming power, secondary surfactants to

improve and condition the hair, additives to complete the formulation

and special effects. Shampoos that are used in babies should be mild,

fragrance free and should not irritate the eyes [33,34].

Use of Emollients

Dry skin is seen in preterm, post term, intra uterine

growth retardation babies, neonates under radiant warmers and

phototherapy, and in children with conditions like atopic dermatitis,

ichthyosis, contact dermatitis and psoriasis. Various factors like

bathing in hot water, frequent washing and use of harsh detergents,

exposure to low humidity like air-conditioned environment and cold

climate will worsen the dryness of the skin. Ceramides, cholesterol,

free fatty acids and NMF present in the stratum corneum contribute to

the maintenance of the skin hydration and integrity of the barrier

function. NMF and free fatty acids play an important role in the

maintenance of low pH in the stratum cornuem and in turn barrier

integrity [35]. Skin of neonate has been observed to have less hydration

of the skin surface, thinner stratum corneum and epidermis, less NMF and

increased water loss [36]. Similarly, reduced levels of NMF has been

observed in the stratum corneum of infant skin. Washing the skin with

soaps removes the lipids and NMF resulting in an increase in the pH of

the stratum corneum and altered homeostasis of the skin. Hence liquid

cleansers or if not affordable, judicious use of mild cleansing bars

would be the ideal recommendation in babies prone for dry skin [35,36].

The baby’s skin is clinically dry but may not appear so. Dry skin leads

to micro and macro fissure formation which results in easy penetration

of allergens and bacteria. Hence, the use of emollients is very

important in order to restore the barrier integrity, prevent infections

and further damage. Gentle application of emollients will help to

enhance and maintain the skin barrier function [11,37] (Strong

recommendation; Level of evidence VII and IV).

Natural olive oil and mustard oil have been used for

many years as emollients. Studies have shown that these disrupt the skin

barrier and hence should not be used [5,38] (Strong recommendation;

Level of evidence II). Vegetable oils high in linoleic acid such as

safflower oil or sunflower oil are recommended for infant’s skin. Skin

barrier recovery occurs faster with sunflower seed oil and petrolatum,

whereas it gets delayed with mustard seed oil, soybean oil and olive oil

[5,38]. Oleic acid content of olive oil inhibits synthesis of

arachidonic acid, increases membrane permeability and TEWL. Mineral oil

has been found to be an effective skin moisturiser by virtue of

emollient and occlusion property. In addition, mineral oil, which has

limited penetration, does not contain the carcinogenic polyaromatic

hydrocarbons and hence has been found to be very safe [39].

Appropriately selected emollients which are petrolatum-based, water

miscible, and free of preservatives, dyes and perfumes could be used in

pre/post term/IUGR babies, neonates under radiant warmers/ phototherapy

and in those infants and children with atopic dermatitis, contact

dermatitis, psoriasis and ichthyosis. Emollients decrease the risk of

invasive infection in preterm infants by prevention of access to deeper

tissues and the blood stream through skin portals of entry [36].

In the case of healthy babies, in whom the stratum

corneum function has been disturbed by use of harsh soaps, emollients

play a significant role, especially during winter. Simpson et al have

shown that application of emollient in babies born in families with high

risk of atopy tends to reduce the risk of developing atopic dermatitis

[40] (Strong recommendation; Level of evidence II). Emollients

marketed as natural, herbal and organic have to be used with caution as

there are limited study data on these and hence, are to be avoided

unless proved to be effective and safe.

Massage

Systematic application of touch is termed as massage.

Massage promotes circulation, suppleness and relaxation of the different

areas of the body and tones of the muscles. It relieves the physical and

emotional stress in the baby and supports the baby’s ability to fulfill

the individual developmental potential. Massage increases the activity

of the vagus nerve which results in increased levels of gastrin, insulin

and insulin like growth factor 1 that enhances the food absorption,

weight gain contributing to increase growth. There is greater bone

mineralization, more optimal behavioral and motor responses in infants

who were given massage. It has been observed that preterm infants who

were given massage had reduced cortisol level and parasympathetic

response, reduced stress response, increased vagal activity and gastric

motility, release of gastrin, improved weight gain and enhanced motor

development. Massage of hospitalized preterm or low birth weight babies

resulted in improved daily weight gain, reduced length of stay in the

hospital and had positive effect on postnatal complications and weight

at 4 to 6 months. In summary, benefits of massage are improved barrier

function, decreased TEWL, improved thermo-regulation, stimulation of

circulatory and gastrointestinal systems, improved sleep rhythm and

enhanced neurological and neuromotor development [41-45].

Touch therapy –massage – by whom? when? where? how?:

Massage may be given by mother, father, grandparents, caregiver or

nurse. Full body massage will need fifteen to thirty minutes of

uninterrupted time and is to be given when the baby is quiet, alert and

active, preferably one to two hours after feed. Massage is to be given

in a warm room. Massage provider should avoid having long nails or

wearing any jewelry in the hands. Massage should be slow and gentle but

firm enough for the baby to feel secure.

Oil Massage

Oil acts as a source of warmth and nutrition and

helps in weight gain of the babies. Coconut oil, sunflower oil,

synthetic oil and mineral oil are being used for massage [5,38,46,47].

Babies massaged with oil showed less stress behavior and lower cortisol

levels than those who were given massage without oil [48]. Thus, oil

massage has multiple benefits and hence is recommended [38,46,48] (Strong

recommendation; Level of evidence VII). Mustard oil has been shown

to cause irritant and allergic contact dermatitis while olive oil is

reported to cause erythema and disruption in skin barrier function

[44,45]. Oil massage is to be avoided during summer, if miliaria rubra

is present. Oil massage should be given before bath during summer and

after bath during winter [38,48.49].

Synopsis of evidence-based recommendations for skin

care in neonates and infants is given in Table I [50] and

assessment of recommendations in Supplementary Table I.

Table I Evidence Based Recommendations for Skin Care in Neonates and Infants

|

Recommendation |

Level of

evidence [50] |

Strength of recommendation |

|

Skin-to-skin care (SSC) for all mothers and newborns without

complications at least for one hour [7,12] |

Level VII |

Strong |

|

Vernix caseosa should not be removed [11,12] |

Level VII |

Strong |

| First bath should

be delayed until 24 hours after birth but not before 6 hours

[13] |

Level VII |

Strong |

| Duration of bath

should not exceed 5-10 minutes [11] |

Level VII |

Strong |

| Liquid cleanser

with acidic or neutral pH preferred as it will not affect the

skin barrier |

Level VII |

Strong |

| function or the

acid mantle [11,17] |

|

|

| Prevention of

diaper dermatitis - Frequent change of diapers [24] |

Level I |

Strong |

| In babies with diaper

dermatitis, frequent change of diapers, use of super absorbent

diapers and protection of perineal skin with a product

containing petrolatum and or zinc oxide [24] |

Level I |

Strong |

| Use of soft

clothes and water for cleansing the diaper area is

encouraged [20] |

Level VII |

Strong |

| Only fragrance

free baby wipes can be used [23] |

Level III |

Strong |

| Nothing should be

applied on the cord stump [10] |

Level VII |

Strong |

| Kangaroo mother

care is recommended for the routine care of preterm and low

birth |

Level VII |

Strong |

| weight newborns

weighing 2000 g or less at birth, as soon as the neonates are

|

|

|

| clinically stable

[12]. |

|

|

| Swaddle immersion

bathing could be adopted, with the training of nursing staff

[29] |

Level II |

Strong |

| Gentle application

of appropriately selected emollients will help to maintain the

barrier function [11,37] |

Level VII |

Strong |

|

Application of emollient in babies born in families with high

risk of atopy tends to

|

Level II |

Strong |

| reduce the risk of

developing atopic dermatitis [40] |

|

|

| Vegetable oils

such as olive oil and mustard oil should not be used [5,38] |

Level II |

Strong |

| Oil massage has

multiple benefits and hence is recommended [38,46,48] |

Level II |

Strong |

Care of Skin in Special Situations

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) occurs in genetically

predisposed children with impaired epidermal barrier function and immune

dysregulation. AD is characterized by chronic relapsing dermatitis with

pruritus and age dependent distribution of skin lesions. Initially, skin

lesions start over the face and trunk followed by extensor aspects and

later involves the flexural areas. Emollients containing ceramides,

lipids and n-palmitoyl ethanolamine and natural colloid oatmeal are

useful in children with atopic dermatitis. Emollients are to be applied

within 3 to 5 minutes after a quick bath (5–10 minutes) in lukewarm

water and patting the skin dry. Frequency of application should be every

4 to 6 hours depending on the degree of dryness. Emollients should be

applied 30 minutes before the application of topical corticosteroid

cream. Proper application of sufficient quantity of emollients will help

to reduce the frequency of flares. In babies at high risk for atopic

dermatitis, application of emollient from birth has been observed to be

safe and effective towards primary prevention of atopic dermatitis [40,

51-53].

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis occurs mostly in the sebum rich

areas of the body like scalp, face and body. The exact etiology is not

known but may be associated with various factors like genetic

predisposition, Malassezia colonization of the skin, dryness of

the body and environmental factors like cold weather. In newborn period,

the maternal hormones may trigger this condition. Usually seborrheic

dermatitis appears by third or fourth week of life and peaks by 3 months

of age. Scaling over the scalp, around the eyes, nose and the folds of

the skin and diaper area may be present. It is usually asymptomatic and

disappears by one to six months of age. Emollients are useful in

infantile seborrheic dermatitis. Hydrocortisone 1% cream has been found

to be of use for lesions on the face. Topical azole antifungal agents

could be used for lesions in the groin [54].

Photoprotection

Routine use of sunscreens has not been a common

practice in the community at large in India. But, in the recent years,

there is increased interest and awareness evinced among the parents,

especially those with children involved in sports. Sunscreens used in

children should ideally provide broad spectrum (ultraviolet A and

ultraviolet B) coverage, good photo stability and should not cause

irritation. Those that contain physical or inorganic filters such as

zinc oxide or titanium oxide are preferable. Liquids, sprays and

alcohol-based gel formulations are likely to cause irritation and hence

are best avoided in children below 12 years. Sunscreens that contain

para amino benzoic acid (PABA), cinnamates and oxybenzone may cause

allergic contact dermatitis. In infants below 6 months of age,

photoprotection with appropriate clothing and headgear is recommended,

rather than use of sunscreens. American Academy of Pediatrics recommends

limitation of sun exposure between 10.00 am and 4.00 pm, use of

protective, comfortable clothing, wide-brimmed hats, sunglasses with

ultraviolet (UV) protection and broad-spectrum sunscreen with Sun

protection factor (SPF) ³15

in infants older than 6 months and children. Sunscreen should be applied

30 minutes before going outdoors with reapplication every 2 hours and

after swimming, excessive sweating, vigorous exercise and toweling.

Application of appropriate quantity (2 mg/cm2)

to all the sun-exposed areas is necessary to provide good photo

protection [55-57].

CONCLUSION

Evidence based standard recommendations for care of

the skin of newborn babies and infants will facilitate the improvement

of quality of skin care of the babies which in turn will have a positive

impact on their future health. These recommendations could be further

revalidated with advent of more scientific data in the years to come.

Contributors: All authors approved the

final version to be published, and are accountable for all aspects of

the work to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity

of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This activity was supported with

academic grant from Johnson & Johnson Pvt Ltd, India, to Indian Academy

of Pediatrics. The funding agency had no role in selecting the experts,

topics selected for discussion, and preparing the guidelines.

Competing interest: None stated.

ANNEXURE 1

Expert Members of the Committee

(in alphabetical order)

Anandan V (Chairperson, IAP Dermatology

chapter), Chennai; Bakul Jayant Parekh, Mumbai; Basavaraj

GV, Bengaluru; Digant D Shastri, Surat; Madhu R

(Secretary, IAP Dermatology chapter), Chennai (Co-convener);

Nedunchelian K (Executive Board member, IAP Dermatology chapter),

Chennai; Remesh Kumar R, Cochin; Santosh T Soans,

Mangalore; Thangavelu S (Executive Board member, IAP Dermatology

chapter), Chennai; Vijayabhaskar C (Treasurer, IAP Dermatology

chapter), Chennai (Convener).

REFERENCES

1. John A. McGrath ,JouniUitto. Structure and

functions of the Skin. In: Griffiths CEM, Barker J, Bleiker T,

Chalmers R, Creamer D, editors. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 9thedn.

West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell; 2016. p.37-84.

2. Fluhr JW, Darlenski R, Lachmann N, et al. Infant

epidermal skin physiology: Adaptation after birth. Br J Dermatol.

2012;166:483-90.

3. Walters RM, Khanna P, Melissa Chu, Mack MC.

Developmental changes in skin barrier and structure during the first 5

Years of Life. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2016; 29:111-18.

4. Thappa DM. Common skin problems in children. Int J

Pediatr. 2002; 69:701 6.

5. Darmstadt GL, Mao-Qiang M, Chi E, et al. Impact of

topical oils on the skin barrier: possible implications for neonatal

health in developing countries. Acta Pediatr. 2002;91: 546-54.

6. Lund CH, Osborne JW. Validity and reliability of

the neonatal skin condition score. J Obst Gyn Neo. 2004;33:320-27.

7. WHO recommendations for management of common

childhood conditions. 2012;1-164. Available from:

https://apps.who.int/ iris/bitstream/ handle/10665/44774/

9789241502825_eng.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2018.

8. Hoath SB, Pickens WL, Visscher MO. Biology of

vernix caseosa. Int J of Cosmetic Sci. 2006; 28:319-33.

9. Singh G, Archana G. Unravelling the mystery of

vernix caseosa. Indian J Dermatol. 2008; 53:54-60.

10. Zupan J, Willumsen Z. Pregnancy, Childbirth,

Postpartum and Newborn Care: A guide for essential practice. 3rd

edition. World Health Organisation 2015; 1-184. Available from:

http//www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent . Accessed September

20,2018.

11. Peytavi UB, Lavender T, Jenerowicz D, et al.

Recommendations from a European Round table Meeting on Best Practice

Healthy Infant Skin Care. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016; 33: 311-21.

12. WHO recommendations on newborn health: guidelines

approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee. World Health

Organization; 2017 (WHO/MCA/17.07). Available from:

https://apps.who.int › iris › bitstream › handle ›

WHO-MCA-17.07-eng.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2018.

13. WHO recommendations: Intrapartum care for a

positive childbirth experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available from https:// apps.who.int ›

iris › bitstream › WHO-RHR-18.04-eng.pdf. Accessed September 22,

2018.

14. Ness MJ, Davis DMR, Carey WA. Neonatal skin care:

A concise review. Int J Dermatol. 2013; 52:14-22.

15. Smith E, Shell T. Delayed Bathing. International

Child birth Education Association Position Paper. 2017;1-3.

Accessed January 15, 2019. Available from https://icea.org/uploads/

2018/02/ ICEA-Position-Paper-Delayed-Bathing -PP.pdf

16. Rowley S, Voss L. Auckland District Health Board

Newborn Services Clinical Guideline - Human Immunodeficiency Virus

(HIV). Nursing Care of Infants Born to HIV Positive Mothers. 2010.

Accessed January 15, 2019. Available from https:// www.adhb.

govt.nz/newborn/Guidelines/Infection/NursingCare.htm

17. Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and

Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN). Neonatal Skin Care: Evidence-Based Clinical

Practice Guideline, 4th Edition. 2018. Available from

https://www.awhonn.org/store/ViewProduct.aspx?id =11678739 .

Accessed April 12, 2019.

18. Sarkar R, Basu S, Agrawal RK, Gupta P. Skin care

for the newborn. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:593-98.

19. Stamatas GN, Tierney NK. Diaper dermatitis;

etiology, manifestations, prevention and management. Pediatr Dermatol.

2014; 31:1-7.

20. Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and

Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN). Neonatal Skin Care Evidence-Based Clinical

Practice Guideline, 2nd edition. Association of Women’s Health Obstetric

and Neonatal Nurses; 2007. p.1-81.

21. King Edward Memorial hospital, Govt of Wastern

Australia. Neonatal Clinical Guidelines. Accessed on July 23, 2019.

Available from https:// www. Kemh.health.wa.gov.au> WNHS.NEO.Skin-Care-Guidelines.pdf

22. Dhar S. Newborn skin care revisited. Indian J

Dermatol. 2007;52:1-4

23. Ehretsmann C, Schaefer P, Adam R. Cutaneous

tolerance of baby wipes by infants with atopic dermatitis, and

comparison of the mildness of baby wipe and water in infant skin. J

European Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001; 15:16-21.

24. Heimali LM, Storey B, Stellar JJ, Davis KF.

Beginning at the bottom. Evidence –based care of diaper dermatitis. MCN

Am J Matern Child Nurs 2012; 37:10-6.

25. Madhu R. Skin care for newborn. Indian J Pract

Pediatr. 2014;16:309-15

26. Afsar FS. Skin care for preterm and term

neonates. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:855-58

27. Taþdemir HÝ, Efe E. The effect of tub bathing and

sponge bathing on neonatal comfort and physiological parameters in late

preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud.

2019;99:103377. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019. 06.008. Epub 2019 Jun 21.

28. Kusari A, Han Am, Virgen CA et al. Evidence–based

skin care in preterm infants. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019; 36:16-23.

29. Edraki M, Paran M, Montaseri S, Nejad MR,

Montaseri Z. Comparing the effects of swaddled and conventional bathing

methods on body temperature and crying duration in premature infants: A

randomized clinical trial. J Caring Sci. 2014;3:83-91.

30. UK Neonatal Skin Care Guideline. 2018. Available

from: http://www.cardiffandvaleuhb.wales.nhs.uk >opendoc.

Accessed April 06, 2019.

31. Mangalgi S, Upadhya N. Variation of body

temperature after sponge bath in stable very low birth weight preterm

neonates. Indian J Child Health. 2017; 4:221-24.

32. Lee JC, Lee Y, Park HR. Effects of bathing

interval on skin condition and axillary bacterial colonisation in

preterm infants. Appl Nurs Res. 2018; 40:34-38.

33. Fernandes JD, Machado MCR, Prado de Oliveira ZN.

Children and newborn skin care and prevention. Ann Bras Dermatol.

2011;86:102-10.

34. Siri SD, Jain V. Infant’s skin and care needs

with special consideration to formulation additives. Asian J Pharm Clin

Res. 2018; 11:75-81.

35. Moncrieff G, Cork M, Lawton S, Kokiet S, Daly C,

Clark C. Use of emollients in dry-skin conditions: consensus statement.

Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013; 38:231-38.

36. Telofski LS, Morello, PA III, Correa MC, Stamatas

GN. The infant skin barrier: can we preserve, protect, and enhance the

barrier? Dermatol Res Pract. 2012. ID 198789. doi:10.1155/2012/198789

37. Garcia Bartels N, Scheufele R, Prosch F, et al.

Effect of standardized skin care regimens on neonatal skin barrier

function in different body areas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010; 27:1-8.

38. Danby SG, AlEnezi T, Sultan A, et al. Effect of

olive and sunflower seed oil on the adult skin barrier: Implications for

neonatal skin care. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013; 30:42 50.

39. Rawlings AV, Lombard KJ. A review on the

extensive skin benefits of mineral oil. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012;

34:511-18.

40. Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, et al.

Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective

atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:818-23.

41. Rosalie OM. Infant massage as a component of

developmental care: Past, present and future. Holist Nurse Pract.

2002;17:1-7.

42. Field T, Diego M, Hernandez- Reef M, et al.

Insulin and insulin –like growth factor -1 increased in preterm infants

following massage therapy. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008; 29:463-66.

43. Mileur ML, LuetkemeierM , Boomer L, Chan G.M.

Effect of physical activity on bone mineralization in premature infants.

J Pediatr. 1995;127:620-25.

44. Field T. Infant massage therapy research review.

Clin Res Pediatr. 2018; 1:1-9.

45. Scafidi F, Field T, Schanberg S. Factors that

predict which preterm infants benefit most from massage therapy. J Dev

Behav Pediatr.1993;176-80.

46. Shankaranarayanan K, Mondkar JA, Chauhan MM,

Mascarenhas BM, Mainkar AR, Salvi RY. Oil massage in neonates: An open

randomized controlled study of coconut versus mineral oil. Indian

Pediatr. 2005; 42:877-84.

47. Ognean ML, Ognean M, Andrean B, Georgian BD. The

best vegetable oil for preterm and infant massage. Jurnalul Pediatrului.

2017; 20:9-17.

48. Field T, Schanberg S, Davalos M, Malphura J.

Massage with oil has more positive effects on neonatal infants. Pre and

Perinatal Psychology J. 1996;11:73-78.

49. Dhar S, Banerjee R, Malakar R. Oil massage in

babies: Indian perspectives. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2013; 14:1-3.

50. Ackley BJ, Swan BA., Ladwig G, Tucker

S. Evidence-based nursing care guidelines: Medical-surgical

interventions. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.p.7

51. Madhu R. Management of atopic dermatitis. Indian

J Pract Pediatr. 2015;17:242-48.

52. Rajagopalan M, Abhishek De, Kiran Godse, et al.

Guidelines on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in India: An Evidence

–based Review and an Expert Consensus. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;

64:166-81.

53. Horimukai K, Morita K, Narita M, et al.

Application of moisturizer to neonates prevents development of atopic

dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:824-30.

54. Hogan PA, Langley RGB. Papulosquamous diseases.

In: Schachner LA, Hansen RC, editors Pediatric Dermatology, Vol

2. 4thedn. Mosby Elsevier 2011. p. 901-51.

55. Tania Cestari, Kesha Buster. Photoprotection in

specific populations: Children and people of color. J Am Acad Dermatol.

2017;76;S111-21.

56. Pour NS, Saeedi M, Semnani KM Akbari J. sun

protection for children: A review. J Pediatr Rev. 2015;3:e155:1-7.

57. Madhu R. Polymorphic light eruptions. Indian J

Pract Pediatr. 2015;17:262-68.

|

|

|

|

|