|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2021;58:144-148 |

|

Extended-Spectrum

b-Lactamase-Producing

Enterobacteriaceae Causing Community-Acquired Urinary Tract

Infections in Children in Colombia

|

|

Jhon Camacho-Cruz, 1

Javier Munoz Martinez,1

Julio Mahecha Cufino,1

German Camacho Moreno,1

Carolina Rivera Murillo,1

Maria Alejandra Suarez Fuentes,1

and Carlos Alberto Castro2

From Departments of 1Pediatrics and 2Medical Epidemiology, FundaciónUniversitaria de Ciencias de la Salud (FUCS) – Hospital de San

José and Hospital Infantil Universitario de San José de Bogotá,

Colombia.

Correspondence to: DrJhon Camacho, Associate Instructor,

Department of Pediatrics FUCS,Calle 10, No.18-75 Bogota, Colombia.

Email:

[email protected]

Received: March 24, 2020;

Initial review: April 29, 2020;

Accepted: December 03, 2020.

|

Objective: To characterize the pediatric patients presenting at the

two pediatric centers in Bogotá, with first isolate urine culture of

community-acquired extended-spectrum

b-lactamase

(ESBL)-producing enterobacteriaceae. Methods: Review of

microbiological data of children between January, 2012 and December,

2018, obtained using the WHONET software. Results: A total

of 2657 Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp and Proteus mirabilis -

positive urine cultures were obtained within a 6-year period; data of

132 patients were finally selected. Frequency of

ESBL-producing bacteria infections in community-acquired urinary tract

infections (UTI) was 5%: 123 E. coli (93.2%), 7 K. pneumoniae

(5.2%), 1 K. oxytoca (0.8%), and 1 P. mirabilis (0.8%).

Conclusion: A predominance of female sex, preschool children, and

lower tract urinary infections were found, as well as a low frequency of

comorbidities. Adequate sensitivity to amikacin and nitrofurantoin was

found in this study.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp, Management,

Prevalence, Sensitivity.

|

|

G

ram-negative bacteria are a common cause

of urinary tract infections (UTIs) in children, and are

frequently being reported as extended-spectrum

b-lactamase

(ESBL)-producing bacteria [1]. Actual incidence of urinary

infections due to ESBL-producing bacteria in children is

difficult to estimate; however, over the last 10 years,

resistance has been gradually increasing around the world [2].

Adult studies report a prevalence of 3% to

16.3% among all UTI patients [1], whereas a prevalence of 10.9%

has been reported in a pediatric study [3]. There are few

pediatric studies, estimating the prevalence and the incidence

of ESBL-producing enterobacteriaceae in community-acquired UTIs.

We report the frequency and the clinical characteristics of

children presenting with urinary infections and a urine culture

with community-acquired ESBL-producing bacteria in two hospitals

of Bogotá.

METHODS

A hospital record review of patients younger

than 18 years was done from the emergency department of Hospital

de San José and Hospital Infantil Universitario de San José in

Bogotá. Children included were those with urinary symptoms or

febrile condition without focus and initially an ESBL-producing

bacteria was isolated for the first time in the urine culture

from January, 2012 to December, 2018. Those with positive urine

cultures for healthcare-associated infections (defined as

hospital-acquired infections during treatment or care for a

medical condition) and reinfections (two or more UTI by

ESBL-producing bacteria) were excluded. Socio-demographic and

clinical variables were evaluated, including additional

diagnoses, underlying pathologies, inpatient manage-ment, and

characteristics related to antibiotic treatment. Information was

collected using an instrument developed by the investigators,

which was completed based on the review and selection of medical

records that met the inclusion criteria. Microbiological

information was obtained using the WHONET 5.6 software (World

Health Organization). Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC)

were also rated and interpreted in accordance with the

recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards

Institute (CLSI) of 2017 [4], measured based on the MicroScan

(Baxter) parameters in Hospital San José and on the VITEK2 (bioMerieux)

automated method, in the Hospital Infantil Universitario de San

José.

Statistical analyses: Information was

stored in a database to be then validated selecting 10% of the

records, and compared against the instruments. A descriptive

analysis of the information was conducted in STATA 12;

qualitative variables were presented with absolute and relative

frequencies, while quantitative variables included central

tendency and scatter measurements, in accordance with the

distribution of the data. This study was submitted and approved

by the ethics and the research on humans committees in both

hospitals.

RESULTS

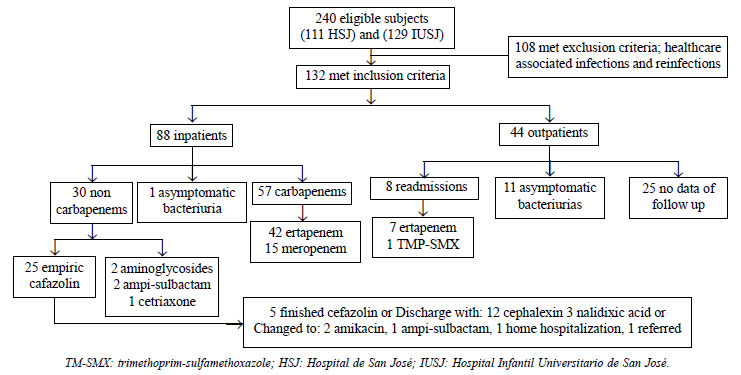

A total of 2657 positive urine cultures were

obtained, of which 240 were reported as ESBL-producing bacteria;

the medical records were reviewed, and in the end, 132 (81.8%

girls) patients were eligible for the final analysis (Fig.

1). Frequency of community-acquired ESBL-producing bacteria

isolates in first UTI was 5%. Of the 132 community-acquired

ESBL-producing bacteria isolates, 123 (93.2%) were from E.

coli, 7 (5.2%) from K. pneumoniae, and 1 (0.8%) each

from K. oxytoca, and Proteus mirabilis.

|

|

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the

study.

|

The median (IQR) age of girls and boys age 4

(1-6.5) year and 0.5 (0.2-1) year, respectively. Other

character-istics of the population are shown in Table I.

Table I Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of Children With First Episode of Urinary

Tract Infection by Community-Acquired ESBL-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (N=132)

| Characteristics |

No. (%) |

| Age (mo) |

|

| <12 |

28 (21.2) |

| 13-24 |

22 (16.7) |

| 25-60 |

45 (34.1) |

| 61-144 |

30 (22.7) |

| >145 |

7 (5.3) |

| Comorbidities |

|

|

Renal and urological comorbiditiesa |

18 (13.6) |

|

Other comorbiditiesb

|

15 (11.4) |

| Diagnosis |

|

|

Asymptomatic bacteriuria |

12 (9.1) |

| Lower UTI |

102 (77.3) |

| Upper UTI |

18 (13.6) |

|

History of hospitalizationc |

28 (21.2) |

|

History of surgeryc |

8 (6.1) |

|

Previous antibiotic therapyc |

50 (37.9) |

| UTId |

49 (37.1) |

|

Congenital malformatione |

26 (19.7) |

| Hospital stay (d), median (IQR)

|

9 (6-11) |

| UTI: Urinary tract

infection; ESBL; Extended spectrum beta lacta-mase;

aRenal and urological comorbidities: hydronephrosis,

pyelectasis, horseshoe kidney, nephrotic syndrome,

bladder diverticula, vesicoureteral

reflux, kidney transplant and nephrostomy; bOther

comorbidities: myelomeningocele, anemia,

chromosomo-pathy, cholestasis, hydrocephalus, systemic

lupus erythematous, pulmonary hypertension. c3 months

prior to ED visit; ddue to ESBL non-producing germs;

epredisposing to UTI. |

Additionally, 49 patients (37.1%) had a

previous history of UTIs, 25 patients (18.9%) had UTI-associated

congenital malformations, 19 (76%) had renal or urologic

conditions (hydronephrosis (n=9), pyelectasis (n=5),

horseshoe kidney (n=2), renal hypoplasia (n=1),

duplex collector system (n=1) and renal duplication (n=1)

and 6 patients (24%) presented with neurological malfor-mations

(myelomeningocele (n=5), hydrocephalus (n=1).

Among this group of malformations, 18 (69.2%) presented a

history of previous UTI. Furthermore, four patients (3.0%) were

in immunosuppressive therapy: two cases of nephrotic syndrome,

one case of systemic lupus erythe-matous and one due to chronic

kidney failure. Nine patients (6.8%) exhibited an additional

risk because of self-medication with amoxicillin, cephalexin,

trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) or metronidazole. 50

patients (37.9%) had no relevant history or risk factors for

UTI.

Imaging findings showed 92 (69.6%) patients

undergoing kidney and urinary tract ultrasound, of which 52

(56.5%) had normal results, 13 (14.1%) exhibited enlarged

kidneys, 9 (9.8%) had evidence of pyelocalicea-lectasia, 7

(7.6%) with kidney atrophy, 6 (6.5%) sediments in urine, 3

(3.2%) hydronephrosis, 1 (1.1%) duplicated pyelocaliceal system,

and 1 (1.1%) neurogenic bladder). Out of 24 patients undergoing

cystouretrography, 12 (50%) were normal, 7 (29.2%) had

vesicoureteral reflux, and 2 (8.3%) bladder diverticula; the

remaining three patients (12.5%) had penile hypospadias,

postvoid residual urine, and decreased posterior urethral

diameter. Finally, of 22 patients undergoing renal gammagraphy,

12 (54.5%) had documented pyelonephritis, 8 (36.4%) were normal,

and 2 (9.1) had kidney scarring.

Sensitivity profiles and co-resistance for

E. coli and K. pneumoniae are illustrated in Table

II. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the

detailed MICs for E. coli for the most important

antibiotics, using automated methods and their relationship to

the CLSI to define sensitivity and resistance.

Table II Specific Sensitivity CLSI 2017 of Each Antibiotic According to the ESBL-Producing

Bacteria Isolated in Positive Urine Culture (N=130)a

|

Escherichia coli

|

Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Antibiotic |

Sensitive |

Intermediate |

Resistant |

Sensitive |

Intermediate |

Resistant |

|

Ampicillin sulbactam, n=130 |

46 (35.4) |

25(19.2) |

52 (40) |

3 (2.3) |

0 |

4 (3.1) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam, n=68 |

56 (82.4) |

3 (4.4) |

5 (7.4) |

4 (5.8) |

0 |

0 |

| Amikacin, n=130 |

121 (93) |

1 (0.8) |

1 (0.8) |

7 (5.4) |

0 |

0 |

| Gentamicin, n=130 |

88 (67.7) |

1 (0.8) |

34 (26.1) |

6 (4.6) |

0 |

1 (0.8) |

| TMP-SMX, n=128 |

33 (25.8) |

0 (0.0) |

88 (68.8) |

3 (2.3) |

0 |

4 (3.1) |

| Nitrofurantoin, n=129 |

92 (71.3) |

28 (21.7) |

2 (1.5) |

5 (3.9) |

1 (0.8) |

1 (0.8) |

| Fosfomycin, n=57 |

52 (91.3) |

0 |

1 (1.7) |

3 (5.3) |

0 |

1 (1.7) |

| Ciprofloxacin, n=129 |

59 (45.7) |

2 (1.6) |

61 (47.3) |

4 (3.1) |

0 |

3 (2.3) |

| Meropenem, n=130 |

130 (100) |

0 |

0 |

130 (100) |

0 |

0 |

|

aOne case each of P. mirabilis and

K.oxytoca were excluded; Values in no. (%); all n not

equal to 130 because not all isolates had the disks for

that antibiotic in the antibiogram. |

After the initial assessment 44 patients,

empiric outpatient therapy was administered with cephalexin in

39 cases (88.7%), nalidixic acid in 2 cases (4.5%), no

antibiotic therapy was prescribed in 2 cases (4.5%), while

TMP-SMX was used in 1 case (2.3). Of these patients, 8 (18.2%)

relapsed and were admitted for ertapenem treatment (7) and 1 was

discharged with TMP-SMX. The remaining 36 patients (81.8%); 11

were considered to develop asymptomatic bacteriuria and 25

patients had no outpatient follow-up information available.

88 patients received hospitalized management,

70 (79.5%) were initially treated with cephalosporins, 7 (7.9%)

with aminoglycosides, and 11 (12.6%) received other antibiotic

therapies. Once the results of the urine culture were available,

57 (64.8%), received specific therapy with carbapenems:

ertapenem (n=42) and mero-penem (n=15); 31

patients (35.2%) received another betalactamic antibiotic

therapy (n=28) and aminogly-cosides (n=3).

Of the 107 patients followed, 12 were

considered asymptomatic bacteriurias, and 95 received empirical

treatment. Of these 95 patients, 74 (77.8%) required switching

over to carbapem management and 21 (22.2%) patients experienced

no change in their antibiotic treatment.

In terms of outcomes, one 7-month old patient

died, with Down syndrome admitted with a diagnosis of upper UTI

and E. coli isolate. The patient received empirical

treatment with ampicillin sulbactam, which was switched on day

three to ertapenem, based on the urinary culture results.

However, the condition of the patient progressed to septic

shock.

Hospitalization in last three months (n=28,

21.2%), recurrent urinary tract infection (n=49, 37.1%),

previous use of antibiotics (n=50, 37.9%) and urinary

tract abnormalities were findings for ESBL producing

community-acquired UTI.

DISCUSSION

This study presents the frequency of UTI

associated with community acquired ESBL-producing bacteria

similar to the levels reported in the international literature

[1,5]. Demographic characteristics include a higher frequency of

females, with an age group distribution similar to the reported

in the world literature [6,7]. The factors related with

ESBL-producing bacteria UTIs are: a history of a previous UTI

non ESBL-producing bacteria, urinary tract malformations,

hospitalization, or antibiotic therapy during the last 3 months

(40% first generation cephalos-porins) [5,8,9]. In terms of

comorbidities, surprisingly most patients were previously

healthy (without any comorbidities), which correlates with the

circulation of ESBL-producing enterobacteriaceae phenotype in

the community.

Median for hospital days is high, similar to

previous studies [10], in addition to a more than two-fold

increase in costs [9,11]. This may be due to the fact that

patients with infections from ESBL-producing bacteria have a

higher risk of hospitalization because of their past history

[6]. Findings of imaging studies were mostly normal and among

the most frequent ultrasound alterations were enlarged kidneys,

followed by pyelectasis; the number of patients who underwent

cystouretrographies and renal gammagraphies was low in contrast

with literature [6] as for most in our population it was their

first infection [12].

The most commonly isolated bacteria was E.

coli, so a more detailed analysis was performed of the

resistance to 8 antibiotics. A very high sensitivity was found

to fosfomycin, nitrofurantoin and amikacin, with similar

findings to those in the spanish study by Pérez, et al. [1]. A

variable sensitivity and resistance was also identified in the

group of betalactamase inhibitors, with a higher resistance in

the ampicillin sulbactam group and intermediate sensitivity,

with MIC approaching the resistance to piperacillin-tazobactam.

It is therefore hypothesized that these are not sound

therapeutic options in this scenario, because of the risk if

increased resistance as has been stated by other authors

[11,13]. A proportion of inpatients were treated with initial

empirical management with cephazolin, achieving a satisfactory

clinical evolution with a negative control urine culture. The

correlation of urinary concentrations that the drug can reach

should be studied [14]. In this series of patients, the typical

risk factors described in the literature were uncommonly seen

[7,15].

It can be suggested that this pathology may

be underdiagnosed or even treated incorrectly, impacting on

bacterial resistance and as a result in prognosis; forcing

health professionals treating this disease to explore the

presence of ESBL in a non-hospital population and without the

risk factors specified in the literature. Other studies should

be done to confirm if there are strains of multi-resistant

bacteria circulating in the community.

Taking into account the observational nature

of this study and the retrospective collection of data, it is

not possible to determine causality. However, this drawback was

offset using different sources of information. Further

analytical and experimental studies are needed to validate the

hypotheses herein discussed and propose an analytical study to

confirm if there are strains of multi-resistant bacteria

circulating in the community. Another limitation of study was

that discs of antibiotic for antibiogram were not uniformly

available for all cases.

UTIs from community acquired ESBL-producing

enterobacteriaceae are a serious public health issue as a result

of the increasing number of cases over the last decade. This

population presents a frequency of 5% for E. Coli and

K. pneumoniae. A predominance of low urinary infection was

found in previously healthy girls of preschool age. The typical

risk factors associated with ESBL-producing bacteria infections

in community acquired UTI were low in this population. This

study reveals the epidemiological and microbiological profile of

these hospitals, good sensitivity was found in this population

for amikacin and nitrofurantoin, so as to select an adequate

treatment and to design alternative non-carbapenem antibiotic

protocols for outpatients, with a view to promote the rational

use of antibiotics. Fosfomycin, piperacillintazobactam, and

other antibiotics require further investigation.

Ethics Clearance: Ethics and the research

on humans committees in both hospitals. Hospital ethics review

board (Comité de ética en investigación con sereshumanos

Hospital de San José, CEISH-HSJ). No. 0369-2018, dated September

17, 2018.

Acknowledgments: Diana Ortiz,

microbiologist of Hospital San Jose and Sandra Peña,

Head,Clinical Laboratory, Hospital InfantilUniversitario de San

José, for their contribution to the microbiological data.

Special thanks to the research division of

FundaciónUniversitaria de Ciencias de la Salud, Hospital de San

José, Bogotá, Colombia, for the translation of the manuscript.

Dr. Pablo VásquezHoyos for his guidance on methodology, and Dr.

Adriana Jiménez for sharing the data used for this article.

Contributors: JCC, JMM, JMC:

conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial

manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; GCM, CRM,

MASF, CCM: designed the data collection instruments, collected

data, carried out the initial analyses, and reviewed and revised

the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript

for important intellectual content, approved the final

manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all

aspects of the work.

Funding: Fundación Universitaria de

Ciencias de la Salud (internal support for academic research

projects).

Competing interests: None stated.

REFERENCES

1. Perez Heras I, Sanchez-Gomez JC, Beneyto-Martin

P, Ruano-de-Pablo L, Losada-Pinedo B. Community-onset

extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in

urinary tract infections in children from 2015 to 2016:

Prevalence, risk factors, and resistances. Medicine (Baltimore).

2017;96:e8571.

2. Fan N-C, Chen H-H, Chen C-L, et al. Rise

of community-onset urinary tract infection caused by

extended-spectrum b-lactamase-producing

Escherichia coli in children. Journal of Microbiology,

Immunology and Infection. 2014;47:399-405.

3. Jurado L, Camacho G, Leal A, et al.

Clinical, phenotypic and genetic characterization of

extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (E.

coli, K. pneumoniae and Proteus spp.) in

community-acquired urinary tract infections [Article in

Spanish]. Infectio: X Encuentro Nacional de Investigadores en

Enfermedades Infecciosas, Medellín 2016.p.24.

4. Wayne P. Performance Standars for

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 27th ed: Clinical and

Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017.

5. Kim YH, Yang EM, Kim CJ. Urinary tract

infection caused by community-acquired extended-spectrum

b-lactamase-producing

bacteria in infants. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93: 260-266.

6. Kizilca O, Siraneci R, Yilmaz A, et al.

Risk factors for community-acquired urinary tract infection

caused by ESBL-producing bacteria in children. Pediatr Int.

2012;54:858-62.

7. Topaloglu R, Er I, Dogan BG, et al. Risk

factors in community-acquired urinary tract infections caused by

ESBL-producing bacteria in children. Pediatr Nephrol.

2010;25:919-25.

8. Rodríguez-Baño J, Pascual A. Clinical

significance of extended-spectrum

b-lactamases.

Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2008;6:671-83.

9. Dayan N, Dabbah H, Weissman I, Aga I, Even

L, Glikman D. Urinary tract infections caused by

community-acquired extended-spectrum

b-lactamase-producing

and non-producing bacteria: A comparative study. J Pediatri.

2013;163: 1417-21.

10. Nieminen O, Korppi M, Helminen M.

Healthcare costs doubled when children had urinary tract

infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing

bacteria. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106:327-33.

11. Sheu CC, Lin SY, Chang YT, Lee CY, Chen

YH, Hsueh PR. Management of infections caused by

extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae:

Current evidence and future prospects. Expert Rev Anti Infect

Ther. 2018;16:205-18.

12. Sundar S, Chinnasami B, Sadasivam K,

Pasupathy S. Role of imaging in children with urinary tract

infections. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2017;4:751-55.

13. Tamma PD, Rodriguez-Bano J. The use of

non-carbapenem b-lactams

for the treatment of extended-spectrum

b-lactamase

infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64: 972-80.

14. Wang KC, Liu MF, Lin CF, Shi ZY. The

impact of revised CLSI cefazolin breakpoints on the clinical

outcomes of Escherichia coli bacteremia. J Microbiol Immunol

Infect. 2016;49:768-774.

15. Balasubramanian S, Kuppuswamy D,

Padmanabhan S, Chandramohan V, Amperayani S. Extended-spectrum

beta-lactamase-producing community-acquired urinary tract

infections in children: Chart review of risk factors. J Glob

Infect Dis. 2018;10:222-25.

|

|

|

|

|