|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57: 124-128 |

|

Impact of Using Different Growth References

on Interpretation of Anthropometric Parameters of Children Aged

8-15 Years

|

|

Preeti Singh1, Sonal Gandhi1, Rajeev Kumar

Malhotra2 and Anju Seth1

From Department of 1Pediatrics,

Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital;

and 2Delhi Cancer Registry, BR Ambedkar IRCH, All India

Institute of Medical Sciences; New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Anju Seth,

Director Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical

College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital, New Delhi 110 001,

India.

Email: [email protected]

Received:

June 11, 2019;

Initial review: July 29, 2019;

Accepted: December 03, 2019.

|

|

Objective: To compare the effect

of the application of three growth references (Agarwal, 1992; Indian

Academy of Paediatrics (IAP), 2015; and World Health Organisation (WHO),

2007) on interpretation of anthropometric parameters in schoolchildren.

Setting: Cross-sectional

school-based study.

Participants: Children 8-15 years

studying in one government school and one private school of Delhi.

Procedure: The age- and

gender-specific standard deviation scores of height-for-age and

BMI-for-age were estimated for each student enrolled, using the three

growth references independently.

Main outcome measure: The

proportion of children with short stature, thinness and overweight/

obesity determined by each growth reference were compared.

Results: A total of 1237 students

participated in the study. A significantly higher proportion of children

(both sexes) were classified to have short stature using WHO 2007

reference (8.8%) as compared to the Agarwal (3.3%) charts and IAP, 2015

references (3.6%). The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was

highest (34.8%) by the IAP, 2015 reference as against 32% by Agarwal

charts and 29.1% by WHO, 2007 reference. Good agreement existed between

the IAP, 2015 reference and Agarwal charts in classifying subjects into

different BMI categories (Kappa=0.82) and short stature (Kappa=0.99).

Conclusions: In view of

differences noted, use of national population derived reference data is

suggested to correctly define growth trajectories in children.

Keywords: Comparison, Growth charts, Obesity,

Short stature.

|

|

A

nthropometry is the universally accepted tool for

the assessment of a child’s growth and nutritional status. The

anthropometric parameters of an individual are interpreted by comparing

with the age- and sex-matched reference data. The interpretation of an

individual child’s anthropometric parameters would depend upon the

reference data used. Clinicians often face a dilemma on the choice of

growth reference for anthropometric assessment among the different

national and international growth references/standards available.

International consensus exist on the use of the World Health

Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards derived from the multi-centric

growth reference study for assessing growth of children up to 5 years of

age [1]. However, there is no similar multi-nation data for children

beyond five years of age, and most nations use local population-derived

reference data for this age group. In India, the growth reference charts

developed by Agarwal, et al. [2] are more than two decades old.

The newer Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) growth references [7] for

Indian children 5-18 years are based on collated national data generated

during last 10 years [7]. Besides, there exist the International WHO

growth reference charts for children 5-19 years of age, which are

primarily based on growth of American children [8,9]. The availability

and use of multiple references for clinical and research purposes can

create confusion amongst healthcare providers and difficulty in correct

interpretation of epidemiological and research data. A difference in

prevalence of stunting, wasting, and thinness in school children from

low income countries was reported on application of WHO, 2007 and NCHS

growth references [10]. Similar inferences were drawn when the

prevalence of overweight and obesity in school children was compared

using the WHO charts, Agarwal charts and International Obesity Task

Force (IOTF) growth reference charts [11].

We compared the effect of the application of three

different growth references; that developed by Agarwal, et al.

[2] (Agarwal reference), IAP growth reference, 2015 [7] (IAP 2015) and

the WHO growth reference [9] (WHO 2007) on estimation of proportion of

school children (aged 8-15 years) classified as having short stature,

thinness, severe thinness, overweight, and obesity.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in July 2016

on schoolchildren aged 8-15 completed years, studying in 3 rd-10th

grades at two schools in northern Delhi. We selected a government and a

private school to enable enrollment of children belonging to different

socio-economic strata and diverse nutritional status. Children suffering

from systemic illnesses or who had undergone a major surgical procedure

likely to interfere with the growth, and those with obvious skeletal or

neurological problem hindering evaluation of physical growth were

excluded. A prior permission from school authorities was obtained.

Passive parent consent and verbal student assent was also taken prior to

enrollment in the study. The parents were given a patient information

sheet containing the relevant details of the study and their written

consent taken. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional

Ethics Committee.

Prior to the start of the study, one researcher was

trained to measure the bodyweight and height using standard procedures.

The investigator collected the date of birth of the enrolled subjects

from the school records. Using standardized equipment and techniques,

the weight and height of all children fulfilling the inclusion criteria

were recorded. The weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg using

electronic digital weighing machine without footwear and minimal

clothing. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable

stadiometer (Seca 222; Seca GmbH & Co. Germany). Body Mass Index (BMI)

was calculated by standard formula.

Using each of the three growth references - Agarwal

reference [2], IAP 2015 [7] and WHO 2007 [9], age- and gender-specific

standard deviation scores (SDS) of height-for-age (HFA-SDS) and

BMI-for-age (BMI-SDS) were calculated for all students. Children with

HFA-SDS < –2 were considered to have short stature across each of the

three reference charts. Definition of thinness/obesity varies among the

different references. For WHO 2007 reference, subjects with BMI-SDS <-2

were considered thin, with BMI-SDS between 1 and 2 as overweight and >2

as obese [12,13]. For IAP 2015 and Agarwal reference charts, the cutoff

of BMI/age <3 rd percentile

and <5th percentile,

respectively were used to define thinness [27]. The cutoff of BMI/age at

23rd adult equivalent (71st centile in boys and 75th centile in girls)

and 27th adult equivalent (90th centile in boys and 95th centile in

girls) was applied to classify overweight and obesity, respectively

according to the IAP 2015 reference charts. As per the Agarwal charts,

overweight and obesity were defined by the BMI /age cut off between 85th

and 95th centile and >95th centile, respectively. The proportion of

children with short stature, thinness, overweight or obesity obtained on

applying each of the three growth references was compared.

Statistical analyses: The data was analyzed by

statistical software SPSS version 20 (IBM Crop, Armonk, NY). For the

purpose of statistical inference, a 2-year interval was used to show the

height and BMI distribution of the subjects enrolled. The three-way

ANOVA test was applied to evaluate the differences in the growth

parameters between the students of the government school and private

school across different age intervals on using the three different

growth references. The McNemar test was applied for height variable and

McNemar-Bomker test was applied for the BMI to assess the agreement

between the two reference charts. A linear mixed model with suitable

covariance structure on the basis of minimum Akaike’s Information

Criteria (AIC) was applied to compare the mean (SD) score

obtained by the use of different reference charts and to assess whether

mean Z score difference is influenced by gender. The Kappa statistic

value was adjusted when prevalence and bias influenced the Kappa

statistic. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered as

statistically significant.

Results

Of the 1256 students screened from the two schools,

1237 students (767 boys) participated in the study; 16 students were

excluded because either the date of birth was unknown or the age was

more than 16 years. Data pertaining to three students was removed as

outliers because they were severely obese (BMI >35 kg/m 2).

The proportion of students enrolled from the government school was

46.6%. The age and sex distribution, and height and BMI of the children

is summarized in Web Table I. The mean SDS for height and

BMI among children in government and private school across all age

groups and both sexes were significantly different on application of the

three growth reference charts (Web Table II, III).

The mean SDS for HFA and BMI for age determined using

the three growth references is given in Table I. Linear

mixed model revealed no significant difference between genders among the

three growth references. However, the mean SDS of HFA estimated by WHO

2007 reference was significantly lower than the Agarwal and IAP 2015

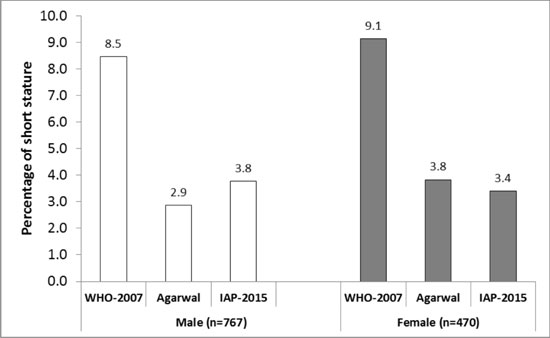

references (P<0.001). Thus, a significantly higher proportion of

children (both sexes) were classified to have short stature using WHO

2007 reference (8.8%) as compared to the Agarwal (3.3%) and IAP 2015

references (3.6%) (Fig. 1). The visual comparison of

distribution of height for age and BMI for age SDS among the three

growth references along with the normal SDS is presented (Web Fig.

1 and 2).

TABLE I Comparison of Standard Deviation Scores of Height for Age and BMI for Age of Children Aged 8-15 Years

Using Three Different Growth Reference Charts (N=1237)

|

Variable |

WHO, 2007 [9] |

Agarwal, 1992 [2] |

IAP, 2015 [7] |

|

Height for age |

|

|

|

|

Girls |

-0.46 (1.19) |

0.45 (1.55) |

0.16 (1.16) |

|

Boys |

-0.35 (1.24) |

0.44 (1.23) |

0.08 (1.18) |

|

Total |

-0.41 (1.22) |

0.44 (1.36) |

0.11 (1.17) |

|

BMI for age |

|

|

|

|

Girls |

0.07 (1.43) |

0.41 (1.31) |

0.25 (1.17) |

|

Boys |

-0.06 (1.68) |

0.66 (1.60) |

0.12 (1.15) |

|

Total |

-0.02 (1.60) |

0.56 (1.50) |

0.17 (1.16) |

|

*All values in mean (SD); P<0.001 for all comparisons between

WHO, 2007 [9] vs IAP, 2015 [7] and Agarwal [2] vs IAP 2015; WHO:

World Health Organization; IAP: Indian Academy of Pediatrics. |

|

|

Fig. 1 Proportion of children aged

8-15 years with short stature using three different growth

reference charts.

|

|

|

Fig. 2 Body mass index (BMI)

categories in children aged 8-15 years using three different

growth reference charts.

|

Figure 2 shows the comparison of the BMI

categories in boys and girls using the three growth reference charts.

Among boys, the IAP reference classified the maximum proportion with

obesity (17.7%), while the Agarwal charts identified the highest

proportion of overweight (20.6%) children. In girls, the IAP reference

reported highest proportion with overweight (21.7%) and obesity (13.4%).

The combined prevalence of overweight and obesity was highest (34.8%) by

the IAP 2015 reference as against 32.0% by Agarwal charts and 29.1% by

WHO2007 reference. The proportion of children (boys and girls combined)

classified as obese was maximum (16.1%) by IAP 2015 as compared to 12.1%

and 10.9% by Agarwal and WHO 2007 references, respectively. The IAP 2015

reference classified least proportion of children with thinness (2.4%)

as compared to Agarwal reference (4.4%) and WHO 2007 reference (11.2%).

The degree of agreement in classifying subjects into different BMI

categories was best between the IAP 2015 and Agarwal references

(Kappa=0.82), followed by WHO and Agarwal (Kappa=0.75) and least with

WHO and IAP references (Kappa=0.60).

Discussion

The comparative assessment of anthropometric para-meters

in school children using three different growth references yielded the

following key observations. The low mean SDS of HFA by WHO 2007

reference resulted in classifying higher proportion of children with

short stature as compared to IAP 2015 and Agarwal reference. Application

of WHO 2007 reference also led to diagnosing higher proportion of

children with thinness as compared to the IAP 2015 reference. Use of IAP

2015 reference accounted for a greater proportion of children classified

with overweight and obesity as compared to Agarwal and WHO 2007

references. Amongst the three growth reference charts, a good

concurrence existed between Agarwal and IAP 2015 references in

identification of short stature, thinness, and overweight/obesity.

The primary limitation of this study was the lack of

assessment of the divergent growth pattern observed in adolescents with

the attainment of puberty. Also, since the objective was primarily to

compare the three growth references, results on interpretation of

anthropometric data cannot be generalized to represent nutritional

status of children in this area.

The higher HFA-SDS of the subjects on application of

IAP 2015 reference charts as compared to WHO 2007 reference shows that

the Indian children are shorter than their Caucasian counterparts.

Similar inference was drawn after the publication of the IAP 2015 growth

reference charts [7,9]. Use of WHO charts will thus lead to an increase

in diagnosis of short stature, creating undue anxiety among parents and

unnecessary referrals to the health facility. The higher mean HFA-SDS

obtained on application of Agarwal reference as compared to IAP 2015

reflects the secular trends in height in India over the past two

decades, and is consistent with previous observations [15,16].

The WHO 2007 reference classified participants in

lower weight strata compared to the IAP 2015 and Agarwal references.

This led to diagnosing higher proportion of children with thinness by

WHO references as compared to the other two references. Likewise,

application of WHO 2007 references underestimated the proportion of

overweight and obese children among the study group as compared to that

obtained by applying IAP 2015 charts. This can lead to missing the

opportunity of identifying these children and offering them appropriate

screening and management. The IAP 2015 BMI centiles/Z scores are lower

as compared to Agarwal Z scores in Agrawal charts, indicating a

steep rise in obesity/overweight in recent times [6,16]. Thus,

application of a similar criteria of 85th and 95th centile to define

overweight and obesity as used by Agarwal, et al. [2] would have

led to a much lower proportion of children being identified with these

conditions on application of IAP 2015 reference. This has been taken

care of in the IAP reference by linking the definition of overweight and

obesity to adult BMI equivalent of 23 and 27, respectively. This led to

lowering of cut-off for defining, and a corresponding higher detection

rate of overweight and obesity by IAP 2015 reference. A rise in the

weight and BMI centiles of both boys and girls on application of recent

reference data from India as compared to Agarwal reference charts has

been reported by Khadilkar, et al. [15] and Marwaha, et al.

[6].

The present study brings out the impact of using

updated national growth reference charts on interpretation of

anthropometric data of older children and adolescents. We conclude that

IAP 2015 growth reference remains in excellent agreement with Agarwal

reference for recognition of short stature while identifying less

children with short stature and more children with overweight and

obesity as compared to WHO 2007 reference. This will have an impact on

screening and management of children with both short stature and

overweight/obesity.

Contributors: PS: execution of the study,

data analysis and writing the manuscript; SG: execution of the study and

writing the manuscript; RKM: contributed in execution of the study, data

analysis and writing the manuscript and AS: conceptualized the paper,

was overall responsible for quality of data collection and maintenance,

modified and finalized the draft.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

References

1. de Onis M, Garza C, Onyango AW, Martorell R, eds.

WHO child growth standards. Acta Paediatrica. 2006; 450:S1-101.

2. Agarwal DK, Agarwal KN, Upadhyay SK, Mittal R,

Prakash R, Rai S. Physical and sexual growth pattern of affluent Indian

children from 5-18 years of age. Indian Pediatr. 1992;29:203-82.

3. Agarwal DK, Agarwal KN. Physical growth in Indian

affluent children (Birth-6 years). Indian Pediatr. 1994;31:377-413.

4. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Choudhury P, Agarwal

KN, Ugra D, Shah NK. IAP growth monitoring guidelines for children from

birth to 18 years. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:187-97.

5. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Chiplonkar SA. Growth

performance of affluent Indian preschool children: a comparison with the

new WHO growth standard. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:869-72.

6. Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Ganie MA, Kanwar R,

Shivaprasad C, Sabharwal A, et al. Nationwide reference data for

height, weight and body mass index of Indian school children. Natl Med J

India. 2011;24:269-77.

7. Indian Academy of Pediatrics Growth Charts

Committee, Khadilkar V, Yadav S, Agrawal KK, Tamboli S, Banerjee M, et al. Revised

IAP growth charts for height, weight and body mass index for 5- to

18-year-old Indian children. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:47-55.

8. WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO

Child Growth Standards: Methods and Development. Length/height-forage,

weight for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass

index-for age: methods and development. http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/technical_report/en/index.html. Accessed

September 10, 2019.

9. de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A,

Nishida C, Siekmann J, et al. Development of a WHO growth

reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health

Organ. 2007;85:660-7.

10. Rousham EK, Roschnik N, Baylon MA, Bobrow EA,

Burkhanova M, Campion MG, et al. A comparison of the National

Center for Health Statistics and new World Health Organization growth

references for school-age children and adolescents with the use of data

from 11 low-income countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:571-7.

11. Stigler MH, Arora M, Dhavan P, Tripathy V, Shrivastav

R, Reddy KS, et al. Measuring obesity among school-aged youth in

India: A comparison of three growth references. Indian Pediatr.

2011;48:105-10.

12. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH.

Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity

worldwide: International survey. BMJ. 2000, 320: 1240-43.

13. Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA. Body

mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents:

International survey. BMJ. 2007;335:194.

14. Sim J, Wright CC. The Kappa statistic in

reliability studies: Use, interpretation, and sample size requirements.

Physical Therapy. 2005;85:257-68.

15. Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV, Cole TJ, Sayyad MJ.

Cross-sectional growth curves for height, weight and body mass index for

affluent Indian children, 2007. Indian Pediatr 2009;46:477-89.

16. Sharma A, Sharma K, Mathur KP. Growth pattern and

prevalence of obesity in affluent school children of Delhi. Public

Health Nutr. 2007;10:485-91.

|

|

|

|

|