|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2017;54:116 -120 |

|

Behavioral Problems in

Indian Children with Epilepsy

|

|

Om P Mishra, Aishvarya Upadhyay, Rajniti Prasad,

Shashi K Upadhyay and *Satya K Piplani

From Department of Pediatrics and *Division of

Biostatistics, Department of Community Medicine; Institute of Medical

Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

Correspondence to: Prof OP Mishra, Department of

Pediatrics, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University,

Varanasi 221005, India.

Email: opmpedia@yahoo.co.uk

Received: February 05, 2016;

Initial review: March 28, 2016;

Accepted: November 29, 2016.

Published online: December 05, 2016.

PII:S097475591600030

|

Objective: To assess prevalence of behavioral

problems in children with epilepsy.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study of

children with epilepsy, and normal controls enrolled between July 2013

to June 2015. Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) was used as a tool to

assess the behavior based on parents reported observation.

Results: There were 60 children with epilepsy in

2-5 years and 80 in 6-14 years age groups, and 74 and 83 unaffected

controls, respectively. Mean CBCL scores for most of the domains in

children of both age groups were significantly higher than controls.

Clinical range abnormalities were mainly detected in externalizing

domain (23.3%) in 2-5 years, and in both internalizing (21.2%) and

externalizing (45%) domains in children of 6-14 years. Younger age of

onset, frequency of seizures and duration of disease had significant

correlation with behavioral problems in both the age groups.

Antiepileptic drug polytherapy was significantly associated with

internalizing problems in older children.

Conclusion: Age at onset, frequency of seizures

and duration of disease were found to be significantly associated with

occurrence of behavioral problems.

Keywords: Child behavior checklist, Co-morbidity, Outcome.

|

|

C

hildren with epilepsy suffer from symptoms of

disease, effect of therapy, risk of recurrence, impairment of brain

function and development of behavioral problems [1]. Psychopathology has

been reported to be associated with epilepsy [2,3]. Psychiatric

disorders can occur in 50-60% of patients with epilepsy [4], and

behavioral co-morbidities to the tune of 43% of cases [5].

Previous studies have reported that these children

have problems of attention, hyperkinesias, thought, low self-esteem,

anxiety and depression [6-10]. Further, cognitive and behavioral

impairments can even occur following a single seizure, and antiepileptic

drugs may also alter behavior to some extent [11].

Previous studies done in children with epilepsy have

addressed a mixed age group (4-16 years) and shown variable results in

different domains [12, 13]; using child behavior checklist (CBCL), a

well standardized tool for detection of behavioral problems in epilepsy

[14,15]. In the present

study, we have assessed behavioral problems in two separate age groups

(2-5 and 6-14 years) using standard CBCL tool for each group and have

tried to find out the differences in pattern of occurrence of behavioral

problems. Additionally, factors associated with development of these

problems were also analyzed in both younger and older age groups.

Methods

This was a cross -sectional study conducted on

children with epilepsy who were recruited from the Epilepsy Clinic and/

or Out Patient Department (OPD) at Institute of Medical Sciences,

Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. Purposive sampling method was used

for the selection of cases during the period of July 1, 2013 to June 30,

2015. The protocol of the study was approved by institutional ethical

committee, and informed consent was obtained from the parents or

authorized representative of each child.

Children of 2-14 years age group of both gender

having idiopathic epilepsy, defined as history of occurrence of 2 or

more episodes of unprovoked focal or generalized seizures having normal

cranial CT/MRI scan and normal/ abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG)

[16]. Controls were recruited from the OPD of Pediatrics who came for

their routine health check-up and were found healthy, and they belonged

to similar age group as of patients with epilepsy. Exclusion criteria:

Patients with the diagnosis of symptomatic epilepsy syndromes, epileptic

encephalopathy, febrile seizures, cerebral palsy, developmental delay,

mental retardation, neuro-degenerative and metabolic disorders,

neurotuberculosis, and neurocysticercosis were excluded from the study.

Developmental delay was labelled on the basis of

history and developmental assessment, and Binet-Kulshrestha Intelligence

Scale was used for intelligent quotient (IQ) assessment in all cases.

Moderate and severe developmental delay/mental retardation cases were

excluded. Detailed information regarding age of onset, types of seizures

(partial/generalized), frequency, duration of disease, antiepileptic

medications, compliance to treatment, control of seizures and family

history were recorded. The IQ was categorized as average when score was

ranging between 90-109 and below average when it was between 75-89. The

frequency of seizure was defined as per Sabbagh, et al. [17]. All

patients were receiving antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin sodium/ sodium

valproate/ carbamazepine/ clobazam) either as monotherapy or in

combinations of two or three. Children who were admitted for acute

control of seizures were assessed once it was controlled and they were

discharged from the hospital. Contolled seizure was defined as cases who

were seizure free for at least 6 months before assessment and those who

had recurrence of seizures despite antiepileptic medications were

considered as uncontrolled seizure. Revised Kuppuswamy scale was [18]

was used for the assessment of socio-economic status.

Assessment for behavioral problems was done by a

clinical psychologist. The native language of the study population was

Hindi and the questions were translated from English version of CBCL by

a language expert, and same questions were asked to each

parent/caregiver and also to those who could not read, and the responses

were recorded in the three-point scale of the Achenbach CBCL [19]. The

CBCL (2001 version) included 100 items for 2-5 years age-group and 113

for 6-14 years age-group, and parents reported inventory was used for

the study. Parents rated their child’s behavior on a three-point Likert

scales: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true

or often true) and took 30-45 min to complete. The scale has

standardized normative scores for age and gender encompassing behavioral

dimensions such as emotionally reactivity, anxious/depressed, somatic

complaints, withdrawn, sleep problems, attention problems, and

aggressive behavior in 2 to 5 year age group; and anxious/depressed,

withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, social problems, thought

problems, attention problems, rule breaking and aggressive behavior

problems in the age group of 6-14 years. It also provided a total

behavior problem score and two second-order factor scores for

internalizing problems (emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, somatic

complaints, withdrawn and sleep problems) and externalizing behavior

(attention problems and aggressive behavior in younger age group and

rule breaking and aggressive behavior in older children). Counseling was

provided to children and families having clinical range abnormalities,

and non-responders were referred to psychiatrist for pharmacotherapy.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using

SPSS software version 16.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). Student’s t-test was used

to compare the observations of patients with controls. Chi-square test

was applied for comparisons of data of proportions. Yates correction was

done wherever required and relative prevalence with confidence intervals

were also calculated. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated

for the factors such as age of onset, frequency of seizure and duration

of disease and Spearman’s correlation coefficient for antiepileptic drug

polytherapy with the development of behavioral problems. A P

value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

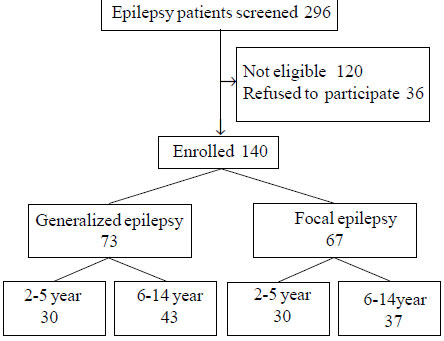

A total of 140 children with epilepsy and 157 healthy

controls in a similar age group were enrolled (Fig. 1),

and were further sub-divided into two age-groups: 2-5 years (60 epilepsy

and 74 controls) and 6-14 years (80 epilepsy and 83 controls). The mean

(SD) age of onset of disease was 2.6 (1.8) years and 4.9 (2.3) years in

2-5 and 6-14 years age-group, respectively. There were 41 males in 2-5

years and 51 in 6-14 years age-groups in cases with epilepsy. In 2-5

years age group, 31(51.7%) received sodium valproate, 10 (16.7%)

phenytoin sodium and 19 (31.7%) cases drugs in combinations (levetiracetam,

carbamazepine/oxcarbamazepine, clobazam); The corresponding figures in

6-14 years age-group were 45 (56.2%), 10 (12.5%) and 25 (31.3%),

respectively.

|

|

Fig. 1 Details of enrolment of the

children with epilepsy.

|

There were no significant differences as regard to

total behavioral problems between children on monotherapy as compared to

polytherapy in both younger (10.5% vs 17.1 %, P=0.35) as

well as older age groups (35% vs 41.5%, P=0.41),

respectively. A relatively higher percentage of children with below

average IQ had total behavioral problems in comparison to those who had

average IQ in both younger (18.6% vs 13.6%, P=0.96,

relative prevalence (RP) 1.15, confidence interval (CI) 0.25- 5.30) as

well as older age group (49% vs 34%, P=0.15, RP 1.03, CI

0.39-2.75), but the differences were found to be insignificant.

Thirty nine (65%) children in 2- 5 years group and 44

(55%) in 6-14 years had controlled seizures and the rest had

uncontrolled seizures at the time of assessment. In younger age-group,

there was no significant difference in the occurrence of behavior

problems between children with controlled and uncontrolled seizures

(2.5% vs 9.5%, P=0.25, RP 0.18, CI 0.48-12.37). However,

in the older age group, children with uncontrolled seizures had higher

incidence of behavior problems than children with controlled seizures

(50% vs 18.1%, P=0.003; RP 2.44, CI 0.07-0.50). None of

the parents of cases had any history of psychological problems. No

significant differences in mean values of different domains were found

in children on monotherapy versus polytherapy in both age groups.

However, in the 6-14 years age-group, uncontrolled seizures were

significantly (P<0.05) associated with internalizing behavioural

problems.

TABLE I CBCL T Scores in Controls and Children With Epilepsy in 2-5 Years-Age Group

|

Domains |

Controls(n=74) |

Epilepsy(n=60) |

|

†Emotionally reactive |

53.4 (5.0) |

55.5 (5.0) |

|

Anxious/depressed |

52.8 (3.5) |

52.5 (3.4) |

|

Somatic complaints |

51.1 (3.2) |

50.7 (2.5) |

|

#Withdrawn |

51.2 (3.2) |

53.6 (5.9) |

|

Sleep problems |

50.6 (1.4) |

50.9 (2.1) |

|

*Attention problems |

54.6 (5.1) |

61.2 (6.2) |

|

*Aggressive behavior |

54.3 (4.3) |

59.5 (6.7) |

|

Internalizing problems |

45.7 (7.6) |

48.1 (7.6) |

|

*Externalizing problems |

51.4 (7.6) |

60.2 (5.5) |

|

*Total behavior problems |

48.3 (9.1) |

53.0 (5.5) |

|

All values in mean (SD); *P<0.001; #P=0.004,† P=0.021. |

TABLE II CBCL T Scores in Controls and Children With Epilepsy in 6-14 Years Age-group

|

Domains |

Controls |

Epilepsy |

P value |

|

(n=82) |

(n=80) |

|

|

Anxious/depressed |

50.3 (2.4) |

53.9 (5.7) |

<0.001 |

|

Withdrawn/depressed |

55.2 (5.2) |

58.6 (8.6) |

0.003 |

|

Somatic complaints |

56.7 (6.4) |

55.8 (7.2) |

0.788 |

|

Social problems |

53.7 (3.7) |

57.2 (5.7) |

<0.001 |

|

Thought problems |

50.8 (2.3) |

51.0 (3.6) |

0.622 |

|

Attention problems |

53.5 (3.9) |

57.6 (6.0) |

<0.001 |

|

Rule breaking behavior |

53.4 (5.2) |

55.1 (5.8) |

0.021 |

|

Aggressive behavior |

58.9 (7.9) |

65.9 (9.6) |

0.001 |

|

Internalizing problems |

49.4 (7.6) |

53.9 (10.1) |

0.002 |

|

Externalizing problems |

56.3 (7.1) |

61.9 (8.5) |

<0.001 |

|

Total behavior problems |

50.9 (6.2) |

56.6 (7.8) |

<0.001 |

|

All values mean (SD). |

Mean values of behavioral scores in patients with

epilepsy aged 2-5 years were significantly higher as compared to control

in the CBCL domains of emotional reactivity (P=0.021), withdrawn

(P=0.004), attention problems (P<0.001), aggressive

behavior (P<0.001), externalizing (P<0.001) and total

behavior problems (P<0.001) (Table I). In the 6-14

years age group, all the domains showed significantly higher scores in

patients than controls, except somatic complaints and thought problems (Table

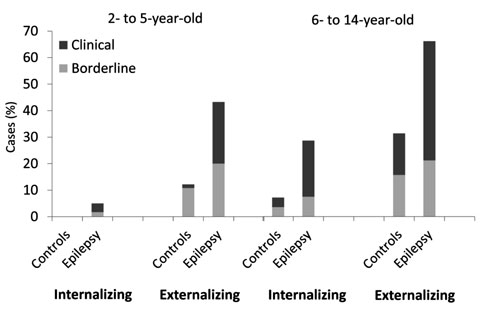

II). Further, 23.3% children with epilepsy of 2-5 years had

externalizing behavior scores, and 21.2% and 45% of 6-14 years had

internalizing and externalizing behavior scores in the clinical range,

respectively (Fig. 2).

|

|

Fig. 2 Internalizing and externalizing

behavioral problems in 2-5 and 6-14 years age-groups in controls

and children with epilepsy.

|

Age of onset of seizure had negative correlations

with total behavior problems (r= -0.289, P<0.05) in 2- 5 years,

and with internalizing (r= -0.230, P<0.05), externalizing (r=

-0.243, P<0.05) and total behavior problems (r= -0.339, P<0.01)

in 6-14 age groups. Frequency of seizure had positive correlations with

externalizing (r=0.41) and total behavior problems (r=0.37)

in younger age-group, and also in older age-group older (r= 0.251 and

0.410, respectively). Duration of disease had positive correlations with

internalizing behavior problems in both younger (r= 0.307) and older age

groups (r= 0.251). Further, in older children, significant positive

correlations were found for antiepileptic drug polytherapy (r= 0.293)

with internalizing behavior problems.

Discussion

In the present study, most of the behavior domains in

children with epilepsy had higher mean scores than controls, but below

the cut-off levels. Externalizing behavioral problems appeared to affect

patients of both the age-groups, but internalizing behavior such as

depression and anxiety were mostly limited to school-age children.

Impaired attention, anxiety, depression,

hyperkinetic, impulsivity, low self-esteem and thought problems are some

of the co-morbidities reported earlier, mostly in mixed age-group of

children [5-7,9]. In

addition, educational underachievement has been also observed in these

children [20]. Behavior problems may not only occur following idiopathic

epilepsy but also due to secondary causes like neurocysticercosis [21].

Abnormal excitability and disrupted synaptic plasticity in the

developing brain can result in epilepsy and subsequently behavior

problems in these patients

[22].

We did not observe any difference in the incidence of

behavioral problems in children with below average IQ in comparison to

cases with average IQ in both the age groups. It may be possible that

effect of IQ was not distinctly seen because of lesser number of cases

in the sub-groups. In contrast, Buelow, et al. [23] observed a

higher risk of occurrence and mean problem scores in cases with low IQ

as compared to patients having middle or high IQ groups, and all types

of problems were found in children with low IQ. Similar to our findings,

Powell, et al. [24] also observed no significant difference in

behavior between children with epilepsy having decreased

seizure-frequency as compared to those with good seizure-control.

A significant effect of age of onset, frequency of

seizures and number of antiepileptic drugs in relation to behavioral

problems have been reported earlier [5,10, 17]. We found younger age of

onset, and frequency of seizures were significantly associated with

behavioral problems. In addition, duration of disease in both age groups

and anti-epileptic drugs in older children also affected the

internalizing problems. However, no difference in behavioural problems

was observed between mono and polytherapy. In contrast, effect of

polytherapy over behavioural problems was found by Datta, et al.

[25] in their patients with epilepsy. It appears that multiple factors

affect the behavioral domains in children with epilepsy. Further, it is

likely that the child’s psychological perception of the disease

situation, especially in older children, could be another contributing

factor to the patient’s behavior during the course of illness. Thus, use

of minimum number of anti-epileptic drugs for seizure-control should be

aimed, to minimize the occurrence of behavioral impairment in these

children.

The strength of the present study is the use of a

standardized validated measurement tool, applied in two age-groups of

population to observe the different behavioral pattern. However, it has

certain limitations as findings are based only on parent-reported

observations. We did not observe the effect of parental educational

level and teacher-report of school-going children, which may limit the

generalizability of the results up to some extent. Further, it would be

also be pertinent to carry out follow-up assessments to document

resolution of problems after discontinuation of treatment.

In conclusion, due attention should be given for

recognition of behavioral co-morbidities in children with epilepsy. They

need periodic assessment during epilepsy treatment and if abnormalities

are detected, may need counseling and also adjustment on behalf of

parents.

Contributors: OPM, AU, SKU: involved in

the design, conduction, analysis of data and drafting of manuscript; RP:

helped in conduct of study and drafting of manuscript; SKP: performed

the statistical analysis of data.

Funding: None; Competing

interest: None stated.

|

What is Already Known?

• Children with epilepsy can develop

behavioral problems in various domains.

What This Study Adds?

• Behavioral co-morbidities differ in

children with epilepsy in different age-groups, with affection

of externalizing behavior in younger children and both

internalizing and externalizing behavior in older age-group.

|

References

1. Malhotra S, Malhotra A. Psychological adjustment

of physically sick children: Relationship with temperament. Indian

Pediatr. 1990; 27:577-84.

2. Jones R, Rickards H, Cavanna AE. The prevalence of

psychiatric disorders in epilepsy: a critical review of the evidence.

Funct Neurol. 2010;25: 191-4.

3. Gaitatzis A, Trimble MR, Sander JW. The

psychiatric co-morbidity of epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand.

2004;110:207-20.

4. Marsh L, Rao V. Psychiatric complications in

patients with epilepsy: A review. Epilepsy Res. 2002;49:11-33.

5. Choudhary A, Gulati S, Sagar R, Kabra M, Sapra S.

Behavioral comorbidity in children and adolescents with epilepsy. J Clin

Neurosci. 2014; 21:1337-40.

6. Gulati S, Yoganathan S, Chakrabarty B. Epilepsy,

cognition and behavior. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81: 1056-62.

7. Otero S. Psychopathology and psychological

adjustment in children and adolescents with epilepsy. World J Pediatr.

2009; 5:12-7.

8. Hoare P, Mann H. Self-esteem and behavioral

adjustment in children with epilepsy and children with diabetes. J

Psychosom Res. 1994; 38:859-69.

9. Rodenburg R, Stams GJ, Meijer AM, Aldenkamp AP,

Deković M. Psychopathology in children with epilepsy: A meta-analysis. J

Pediatric Psychol. 2005;30:453-68.

10. Austin JK, Risinger MW, Beckett LA. Correlates of

behavior problems in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1992;33:

1115-22.

11. Aldenkamp AP, Bodde N. Behavior, cognition and

epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2005;182: S19-25.

12. Kobayashi K, Endoh F, Ogino T, Oka M, Morooka T,

Yoshinaga H, et al. Questionnaire based assessment of behavioral

problems in Japanese children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav.

2013;7:238-42.

13. Eom S, Eun SH, Kang HC, Eun BL, Nam SO, Kim SJ,

et al. Epilepsy-related clinical factors and psychosocial

functions in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;37:43-8.

14. Allison Bender H , Auciello D, Morrison CE,

MacAllister WS, Zaroff CM. Comparing the convergent validity and

clinical utility of the Behavior Assessment System for Children-Parent

Rating Scales and Child Behavior Checklist in children with epilepsy.

Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13:237-42.

15. Gleissner U, Fritz NE, Von Lehe M, Sassen R,

Elger CE, Helmstaedter C. The validity of the Child Behavior Checklist

for children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:276-80.

16. Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton

P, Lee P, et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions

proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the

International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia. 2005;46:470-2.

17. Sabbagh SE, Soria C, Escolano S, Bulteau C,

Dellatolas G. Impact of epilepsy characteristics and behavioral problems

on school placement in children. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9:573-8.

18. Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. Kuppuswamy’s

socioeconomic scale: updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian J

Public Health. 2012;56: 103-4.

19. Achenbach TM. Achenbach system of empirically

based assessment (ASEBA). Manual for the child behavior checklist

Pre-school (1.5–5 year), 2000 and School (6–18 year). Burlington, USA:

Research Centre for Children Youth and Families, 2001.

20. Singh H, Aneja S, Unni KE, Seth A, Kumar V. A

study of educational underachievement in Indian children with epilepsy.

Brain Dev. 2012; 34:504-10.

21. Prasad R, Shambhavi, Mishra OP, Upadhyay SK,

Singh TB, Singh UK. Cognitive and behavior dysfunction of children with

neurocysticercosis: a cross sectional study. J Trop Pediatr. 2014;

60:358-62.

22. Brooks-Kayal A. Molecular mechanisms of cognitive

and behavioral co-morbidities of epilepsy in children. Epilepsia.

2011;52:S13–20.

23. Buelow JM, Austin JK, Perkins SM, Shen J, Dunn

DW, Fastenau PS. Behavior and mental health problems in children with

epilepsy and low IQ. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:683-92.

24. Powell K, Walker RW, Rogathe J, Gray WK, Hunter

E, Newton CR, et al. Cognition and behavior in a prevalent cohort

of children with epilepsy in rural northern Tanzania: A three-year

follow-up study. Epilepsy Behavi. 2015;51:117–23.

25. Datta SS, Premkumar TS, Chandy S, Kumar S,

Kirubakaran C, Gnanamuthu C, et al. Behaviour problems in

children and adolescents with seizure disorder: associations and risk

factors. Seizure. 2005;14: 190-7.

|

|

|

|

|