Atrial standstill or paralysis has been defined as

the absence of any electrical or mechanical activity of atria [1-3]. In

atrial standstill, there is no evidence of atrial electrical activity in

the surface ECG leads or on electrophysiological evaluation. We report

atrial standstill in acute myocarditis that persisted even after the

resolution of myocarditis.

Case Report

A 10-year-old girl presented with congestive heart

failure (CHF) following an episode of low grade fever. She had no family

history of cardiac illness, pacemaker implantation, embolic events or

skeletal muscle disease. Investigations revealed a normal total

leukocyte count (7x 10

9/L)

with 18% neutrophils. Serum electrolytes were in the normal range. The

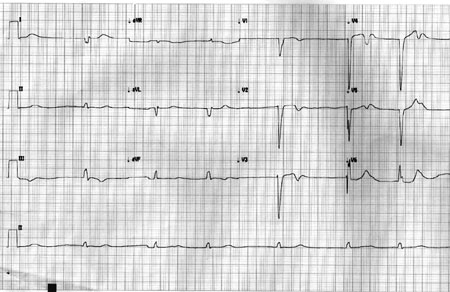

ECG at the time of presentation showed absent P waves and a wide QRS

regular escape rhythm at 40/min (Fig. 1). Cardiac troponin

T was raised (1793 ng/L). Echocardiogram showed hypokinesia of the left

ventricle and mild left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. Her Anti-ds DNA

and anti-nuclear antibody titres were normal. She had received

intravenous immunoglobulins, ampicillin and ranitidine before she was

referred to our unit. We continued conservative management with bed

rest, diuretics, and digoxin. Her CHF improved, and subsequently she was

discharged. At review visit 6 weeks later, she had no CHF but had the

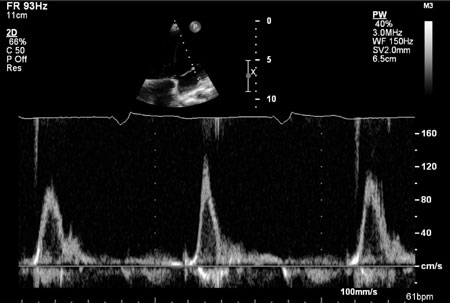

same ventricular escape rhythm and exertional fatigue. Echocardiogram

showed improved LV function (ejection fraction 51%). Mitral and

tricuspid inflow Doppler study showed absence of "a" wave suggestive of

total atrial standstill (Fig. 2). An evaluation done for

neuromuscular disease showed normal muscle strength and normal

electromyography.

|

|

Fig. 1 The 12 Lead ECG showing

idioventricular rhythm with absence of P wave and wide QRS

escape rhythm.

|

|

|

Fig. 2 Mitral inflow pulse wave

Doppler showing absence of ‘a’ wave and paced rhythm at

60/minute.

|

Electrophysiology study (EPS) showed no evidence of

atrial electrical activity. There was no atrial capture even at maximum

pacing output (25mA), from multiple atrial sites (Web Fig.

I), consistent with atrial standstill. She underwent a pacemaker

implantation, and subsequently the right ventricular pacing parameters

were normal. Her ECG after 10 months showed no p waves, and the

fluoroscopy and echocardiography showed no suggestion of atrial

contraction. Interrogation of the pacemaker confirmed that she was

totally pacemaker-dependent.

Discussion

Atrial standstill has been reported to occur in

inherited myopathies, valvular cardiomyopathies, digitalis or quinidine

intoxication, hypoxia, hyperkalemia, myocardial infarction, systemic

lupus erythematous, and Chaga’s disease. Atrial standstill secondary to

myocarditis, persisting long after the acute phase, is extremely rare.

Atrial standstill could be defined as partial or

total [4]. In partial atrial standstill, conduction disturbance within

the right atrium alone is a more common finding. The absence of P waves

in surface ECG occur in sinus node arrest with junctional escape rhythm

which is thus a differential diagnosis of atrial standstill. However, in

sinus arrest, the atria can be shown to be excitable by pacing whereas

in atrial standstill, atria are non-excitable and cannot be captured

even with high pacing outputs. This results in lack of mechanical

functioning of atria, and predispose to intra-atrial thrombus formation.

Our patient had a wide QRS escape rhythm with no P

waves. This indicates an escape rhythm from below the level of His

bundle (Infra-Hisian). The inability to capture the atria even at high

current output during the EPS confirmed atrial standstill in our case.

We used digoxin for LV dysfunction in spite of patient having

bradycardia because digoxin has minimal action on infra-Hisian tissues,

and is less likely to suppress the escape rhythm. However, a stand by

temporary pacemaker was kept ready, and patient was closely monitored.

Isoprenaline, which can be used to increase the heart rate, can also

worsen the conduction in infra-Hisian disease, and hence was not used.

She was closely monitored in the acute phase, and as there was a

possibility that her rhythm may normalize once her myocarditis resolves,

we waited for six weeks before implanting a permanent pacemaker.

Persistent atrial standstill is a rare disorder [5],

and that occurring after myocarditis is even rarer. Straumanis, et al.

[6] have reported a 11-year-old child with biopsy-proven necrotizing

acute myocarditis causing atrial standstill. However, this was transient

and resolved after 3 days of treatment with methylprednisolone. Our

patient had persistence of atrial standstill, even after the ventricular

dysfunction recovered. Abdelwahab, et al. [7] have reported a

case of multiple atrial arrhythmias (atrioventricular node re-entry and

two different focal atrial tachycardias) originating from the remaining

atrial myocardium after global scarring of both atria following a remote

viral myocarditis. Talwar, et al. [8] reported a case series in

which two of the patients had lymphocytic infiltrates on right

ventricular endomyocardial biopsy. In another case series of 11 patients

with atrial standstill reported by Nakazato, et al. [9], three

had histological evidence of chronic myocarditis. None of their patients

had a presentation suggestive of acute myocarditis.

Pathological involvement of atria in atrial

standstill can be localised or diffuse. Our patient likely had a total

atrial standstill as evidenced in mitral pulse wave Doppler showing

absence of ‘a’ wave. As atrial standstill is a well-known cause of

cardiogenic embolism [9], anti-coagulation is mandatory; our patient was

started on Warfarin. The management of patients with atrial standstill

include anticoagulation in all patients, and pacemaker implantation in

patients who have symptomatic bradycardia due to insufficient rates of

escape rhythm.

We conclude that acute myocarditis can rarely cause

extensive damage to the atria causing loss of electrical and mechanical

function. This may herald atrial standstill, which can persist even

beyond the acute phase when other changes have recovered.

Contributors: MAP and SP: case management,

drafting of manuscript; AT and NN: case management critical revision of

manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. Surawicz B. Electrolytes and the

electrocardiogram. Am J Cardiol. 1963;12:656.

2. James TN. Myocardial infarction and atrial

arrhythmias. Circulation. 1961; 24:761.

3. James TN, Rupe CE, Monte R. Pathology of the

cardiac conduction system in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern

Med. 1965;63:402.

4. Lévy S, Pouget B, Bemurat M, Lacaze JC, Clementy

J, Bricaud H. Partial atrial electrical standstill: report of three

cases and review of clinical and electrophysiological features. Eur

Heart J. 1980;1:107-16.

5. Allensworth DC, Rice CI, Lowe G. Persistent atrial

standstill in a family with myocardial disease. Med Am J.

1969;47:775-84.

6. Straumanis, John PW, Henry BC, Christopher LR.

Resolution of atrial standstill in a child with myocarditis. PACE.

1993;16:2196-202.

7. Amir A, John LS, Ratika P, Magdy B, Martin G.

Mapping and ablation of multiple atrial arrhythmias in a patient with

persistent atrial standstill after remote viral myocarditis. PACE.

2009;32:275-7.

8. Talwar KK, Dev V, Chopra P, Dave TH, Radhakrishnan

S. Persistent atrial standstill — clinical, electrophysiological and

morphological study. PACE.1991;14:1274-81.

9. Yuji N, Yasuro N, Teruhikoa H, Masataka S,

Shunsuke O, Hiroshi Y. Clinical and electrophysiological characteristics

of atrial standstill. PACE. 1995;18:1244-54.