|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2016;53: 149-153 |

|

Placebo-controlled Randomized Trial Evaluating

Efficacy of Ondansetron in Children with Diarrhea and Vomiting:

Critical Appraisal and Updated Meta-analysis

|

|

Source Citation: Danewa AS, Shah D, Batra P, Bhattacharya SK, Gupta

P. Oral ondansetron in management of dehydrating diarrhea with vomiting

in children aged 3 months to 5 years: A randomized controlled trial. J

Pediatr. 2016; 169:105-9.

Section Editor: Abhijeet Saha

|

|

Summary

In this double blind randomized placebo-controlled

trial from New Delhi, India, 170 children (age 3 mo to 5 y) with acute

diarrhea with vomiting and some dehydration were randomized equally to

receive either single dose of oral ondansetron or placebo in addition to

standard management of dehydration according to World Health

Organization guidelines. Failure of oral rehydration therapy (ORT),

administration of unscheduled intravenous fluids, and amount of oral

rehydration solution intake in 4 hours were the primary outcomes.

Failure of ORT was significantly less in children receiving ondansetron

compared with those receiving placebo (31% vs 62%; P<0.001;

RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.35, 0.72). The oral rehydration solution consumption

was significantly more in the ondansetron group (645 mL vs 554 mL;

mean difference 91 mL; 95% CI: 35, 148 mL). Patients in the ondansetron

group also showed faster rehydration, lesser number of vomiting

episodes, and better caregiver satisfaction. The authors concluded that

a single oral dose of ondansetron, given before starting ORT to children

<5 years of age having acute diarrhea and vomiting, results in better

oral rehydration.

Commentaries

Evidence-based Medicine Viewpoint

Relevance: Clinical experience suggests that

vomiting is often a significant barrier to successful oral rehydration

therapy (ORT) in children with acute gastroenteritis. Vomiting can

result in reluctance among family members/caregivers to administer

adequate quantity of oral fluid; it sometimes impels physicians to

prescribe intravenous fluids to avoid the delays associated with oral

rehydration; and it also creates difficulties for individual children to

accept oral rehydration salt (ORS) solution in appropriate amounts.

Available systematic reviews suggest that anti-emetic therapy

administered in conjunction with ORS solution (ORS) may enhance the

efficacy of ORT [1-4]. Against this background, the recent trial by

Danewa, et al. [5] comparing oral ondansetron versus

placebo for management of dehydration among children with diarrhea

having associated vomiting, is a significant value addition to existing

literature. The authors identified some of the lacunae in existing

knowledge [1] and addressed these. Table I summarizes the

main features of the trial.

Table I Summary of the Trial

|

Objective |

To

compare the efficacy and safety of orally administered

ondansetron versus placebo, for the management of dehydration in

children prescribed oral rehydration therapy for diarrhea and

vomiting. |

| Study

design and setting |

Single center, placebo controlled double-blinded, randomized

controlled trial in a tertiary care, teaching hospital in Delhi,

India. |

|

Population (P) |

Inclusion criteria: Children (3mo-5y) with diarrhea (<14 d

duration) with WHO-defined ‘some dehydration’ and >2 episodes

vomiting in the preceding 6 h prior to presentation. Exclusion

criteria: Children with severe acute malnutrition, altered

sensorium, seizures, peripheral edema, paralytic ileus, previous

receipt of any anti-emetic medication and/or prior intravenous

fluids. |

|

Intervention (I) |

Ondansetron (oral) (0.2 mg/kg) just before starting ORT. Unlike

previous trial, the investigators used precise rather than

empiric dosage. |

|

Comparison (C) |

Placebo (oral) administered in a similar dose. |

|

Outcomes (O) |

Efficacy: Failure of ORT (defined as persistence or worsening of

dehydration after 4 h of therapy); Need for intravenous fluids

(with clear criteria for the same); Total volume of ORS accepted

within 4 hours of treatment; Vomiting episodes; Duration of

dehydration; Parent/caregiver satisfaction with treatment.

Safety: Adverse events (diarrhea, headache, rash) recorded by

investigators during therapy. |

|

Time-frame (T) |

All

outcomes were assessed within a short time-frame of 8 hours.

|

|

Sample size |

Sample size was calculated a priori for each of the three

primary outcomes, and the total number randomized was adequate

to cover for any drop outs following randomization.

|

|

Similarity of groups at |

Children in the intervention and comparison groups had similar

characteristics at baseline in terms of age |

|

baseline |

distribution, gender, duration of diarrhea, dehydration status,

nutritional status, and vomiting frequency. |

Critical appraisal: Critical appraisal of the

trial [5] adapting various standard tools [6,7] is summarized in

Table II. The trial fulfilled all criteria for low risk

of bias. It is interesting to note that children in the ondansetron

group could take 75 mL/kg fluid over 4 hours. Incidentally this is the

exact target volume for children with ‘some dehydration’. In contrast,

those in the placebo group could take an average of 63.7 mL/kg in the

same duration. This means that in real world situations, children having

vomiting are unable to accept the required volume of ORS solution. While

this readily explains why nearly two-thirds of children in the placebo

group required another round of ORT or intravenous fluids, it also

suggests that current protocols recommending 75 mL/kg ORS solution may

be chasing a futile goal in such children. The issue is somewhat

complicated by the fact that majority of participants in this trial were

infants receiving breast milk. Since the number of breastfeeding infants

in each group and estimation of number/volume of feeds was not measured,

its implications are unclear.

Table II: Critical Appraisal of The Trial

| Trial

Parameter |

How it was

Done |

Interpretation |

| Randomization |

The allocation

sequence was generated by a computer program. |

Adequate |

|

Varying block

sizes were used to allocate participants. |

|

| Allocation

concealment |

The allocation

sequence was not revealed to anyone involved in the |

Adequate |

|

study.

Intervention and placebo were made available in identical

bottles |

|

|

labelled with

a code representing the allocation. |

|

| Blinding |

Participants,

their parents, and professionals who delivered the |

Adequate |

|

intervention,

managed the children, and assessed the outcomes, were

|

|

|

all blinded.

The intervention and placebo were prepared to have similar

|

|

|

concentration,

taste, colour, and odour. They were packaged in identical

|

|

|

bottles with no distinguishing features. The same volume (mL/kg)

was |

|

|

administered

to both groups. |

|

| Selective

outcome reporting |

All relevant

short-term outcomes were included in this trial. |

Adequate |

| Incomplete

outcome |

Of the 170

participants randomized, only 3 (1.8%) did not complete the

|

Adequate |

| reporting |

study per

protocol. This low attrition is probably owing to the short term

|

|

|

outcomes in

the trial. |

|

| Statistical

methods |

Appropriate

statistical tests were used for most outcomes. Per protocol |

Adequate

|

|

analysis was

chosen, rather than intention-to-treat analysis. However,

|

|

|

as the

attrition rate was very low, it may not compromise the validity.

|

|

| Main results (Ondansetron

|

Failure of

ORT: RR 0.50 [95% CI 0.35, 0.72], NNT rounded to 4 Need |

Ondansetron

|

| vs placebo) |

for

intravenous. fluids: RR 0.56 [95% CI 0.30, 1.07], NNT 9Volume of

|

superior for

all |

|

ORS accepted:

Mean difference 91 mL [95% CI 35 mL, 147 mL] |

outcomes

except |

|

Vomiting

episodes: Mean difference -1.80 [-2.5, -1.1] Duration of

|

need for |

|

dehydration:

These are presented as survival curves and demonstrate |

intravenous

fluids. |

|

superiority of

ondansetron starting from 3 hours after administration.

|

|

|

Parent/care-giver satisfaction: Statistically significant

superiority |

|

|

with

ondansetron for each component. However, overall score not

|

|

|

presented;

hence need not be synonymous with clinical significance.

|

|

|

Adverse

events: No events in either group, hence differences (if any)

|

|

|

cannot be

determined. |

|

| Overall

impression |

Validity: RCT

with a low risk of bias.Results: Clinically meaningful

|

|

|

results for

almost all outcomes.Applicability: Applicable in most

|

|

|

health-care

settings. |

|

|

ORT: Oral rehydration therapy; NNT: Number needed to treat;

RCT: Randomized controlled trial. |

On the other hand, if children were able to take 75

mL/kg ORS solution within 4 hours, why did some require intravenous

fluids? This issue gains even more importance considering that all the

previous trials and systematic reviews on this subject reported

statistically significant reduction in the need for intravenous

rehydration. The absence of this finding here [5] necessitates updating

current systematic reviews.

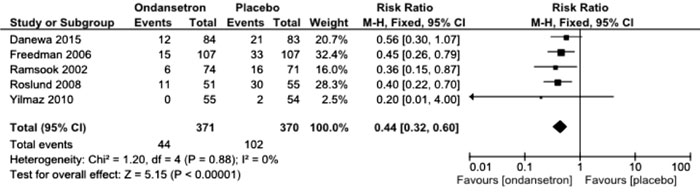

Literature search was conducted through PubMed and

the Cochrane Library (search terms: ondansetron diarrhea) on 14 th

January 2016, to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing

ondansetron (oral) versus placebo in children with diarrhea and

vomiting, for clinically meaningful outcomes. Trials reporting studies

in children with specific causes of diarrhea (such as irritable bowel

syndrome) were excluded. A total of 141 and 104 citations, respectively

were found. Screening by title, abstract and full text resulted in

identifying 5 eligible RCTs, including the current trial [5,8-11]. One

trial [12] was excluded as it used intravenous ondansetron.

Web

Table I summarizes the key features of the additional

trials. Fig. 1 presents the updated meta-analysis

incorporating data from the present trial for the pertinent outcome. The

updated relative risk is 0.44 [95% CI 0.32, 0.60; 5 trials, 741

participants; I2=0),

confirming that ondansetron reduces need for intravenous fluids by about

55%.

|

|

Fig. 1 Updated meta-analysis of

ondansetron versus placebo for need of intravenous fluids.

|

Although ondansetron is perceived as a relatively

safe medication, it has the potential to create unpleasant [8,9,13] and

even dangerous side effects [14-16]; although the dose, route, and

participant characteristics may have a bearing. Rarer side effects may

not be observed in a trial with limited participants; this point has

been emphasized by the investigators also [5]. In the absence of a

surveillance system to identify adverse events, physicians themselves

should carefully monitor and report adverse effects. Since orally

administered ondansetron has a short half-life of 3-4 hours [17], it may

be prudent to monitor recipients for at least 24 hours. It is pertinent

that two professional European societies have recommended caution before

ondansetron is routinely used [18].

Extendibility: This well-designed and

well-executed RCT was conducted in a setting familiar to most healthcare

facilities in India and much of the developing world. Participant

selection, intervention adminis-tration, healthcare setting, and outcome

monitoring were similar to the real-world scenarios in centers equipped

to handle acute diarrhea and dehydration. Therefore, the results are

readily extendible to similar settings across the world. It may be

possible to cautiously extend the results to field/community settings

where a combination of ondansetron and ORT administration may begin at

home/primary centres before/while the dehydrated child is transferred to

a facility with resources/personnel to administer intravenous fluids if

required. The enthusiasm for using ondansetron should be tempered with

caution concerning its potential adverse effects.

Conclusion: Ondansetron administered before ORT

in children with diarrhea having additional vomiting results in better

rehydration. However, physicians should be careful to monitor and

report (note emphasis) any side effects of ondansetron occurring in

the first 24 hours. These results are not extendible to children

presenting with severe dehydration.

References

1. Fedorowicz Z, Jagannath VA, Carter B.

Anti-emetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis

in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

2011;9:CD005506.

2. Carter B, Fedorowicz Z. Antiemetic treatment

for acute gastroenteritis in children: An updated Cochrane

systematic review with meta-analysis and mixed treatment comparison

in a Bayesian framework. BMJ Open. 2012;19:2.

3. Freedman SB, Pasichnyk D, Black KJ,

Fitzpatrick E, Gouin S, Milne A, et al. Gastroenteritis

therapies in developed countries: Systematic review and

meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128754.

4. Freedman SB, Ali S, Oleszczuk M, Gouin S,

Hartling L. Treatment of acute gastroenteritis in children: An

overview of systematic reviews of interventions commonly used in

developed countries. Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8: 1123-37.

5. Danewa AS, Shah D, Batra P, Bhattacharya SK,

Gupta P. Oral ondansetron in management of dehydrating diarrhea with

vomiting in children aged 3 months to 5 years: A randomized

controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2015; Dec 1. pii:

S0022-3476(15)01165-8.

6. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Critical

Appraisal Tools. Available: from: http://www.cebm.net/critical-appraisal/. Accessed January 14,

2016.

7. Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. Available from: http://ohg.cochrane.org/sites/ohg.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Risk%20of%20bias%20assessment%20tool.pdf.

Accessed January 14, 2016.

8. Roslund G, Hepps TS, McQuillen KK. The role of

oral ondansetron in children with vomiting as a result of acute

gastritis/gastroenteritis who have failed oral rehydration therapy:

A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:22-9.

9. Freedman SB, Adler M, Seshadri R, Powell EC.

Oral ondansetron for gastroenteritis in a pediatric emergency

department. N Engl J Med. 2006;354: 1698-1705.

10. Yilmaz HL, Yildizdas RD, Sertdemir Y.

Clinical trial: oral ondansetron for reducing vomiting secondary to

acute gastroenteritis in children – a double-blind randomized study.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:82-91.

11. Ramsook C, Sahagun-Carreon I, Kozinetz CA,

Moro-Sutherland D. A randomized clinical trial comparing oral

ondansetron with placebo in children with vomiting from acute

gastroenteritis. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:397-403.

12. Rerksuppaphol S, Rerksuppaphol L. Efficacy of

intravenous ondansetron to prevent vomiting episodes in acute

gastroenteritis: A randomized, double blind, and controlled trial.

Pediatr Rep. 2010;2:e17.

13. Ondansetron side effects. Available from: http://www.drugs.com/sfx/ondansetron-side-effects.html. Accessed

January14, 2016.

14. Freedman SB, Uleryk E, Rumantir M,

Finkelstein Y. Ondansetron and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias: A

systematic review and post marketing analysis. Ann Emerg Med.

2014;64:19-25.

15. Moazzam MS, Nasreen F, Bano S, Amir SH.

Symptomatic sinus bradycardia: A rare adverse effect of intravenous

ondansetron. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5:96-7.

16. Moffett PM, Cartwright L, Grossart EA,

O’Keefe D, Kang CS. Intravenous ondansetron and the QT interval in

adult emergency department patients: An observational study. Acad

Emerg Med. 2016;23:102-5.

17. The Comprehensive Resource for Physicians,

Drug and Illness Information. Available from: http://www.rxmed.

com/b.main/b2.pharmaceutical/b2.1.monographs/CPS-

%20Monographs/CPS-%20(General%20Monographs-%20Z)/ZOFRAN.html.

Accessed January 14, 2016.

18. Guarino A, Ashkenazi S, Gendrel D, Lo Vecchio

A, Shamir R, Szajewska H; European Society for Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition; European Society for

Pediatric Infectious Diseases. European Society for Pediatric

Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition/European Society for

Pediatric Infectious Diseases evidence-based guidelines for the

management of acute gastroenteritis in children in Europe: Update

2014. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59:132-52.

Joseph L Mathew

Department of Pediatrics, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India.

Email: [email protected]

Pediatric Gastroenterologist’s Viewpoint

Vomiting associated with acute gastroenteritis is a

distressing symptom for children and their parents. Persistent vomiting

is also one of the main causes of failure of oral rehydration therapy

and need for intravenous rehydration. Decision of using antiemetic drugs

should be guided by their efficacy, side effects and cost. A cochrane

review published in 2011 and a systemic review published in 2012

concluded that use of ondansetron when compared to placebo increased the

proportion of patients with cessation of vomiting (RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.29,

1.61), reduced the need of immediate hospitalization (RR 0.40, 95% CI

0.19, 0.83) and need for intravenous rehydration (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.29,

0.59) [1,2]. All studies done so far were done in emergency department,

in children with persistent vomiting and mild to moderate dehydration.

There is lack of evidence from ambulatory settings, in children with

vomiting and no dehydration, and in children with moderate to severe

acute malnutrition. Most of studies have used a single dose. Studies

have also reported prolongation of diarrhea in children who received

ondansetron [1]. There is also some concern regarding prolongation of QT

interval in patients with potential electrolyte abnormalities who

receive intravenous ondansetron [3].

In the present study, authors evaluated the role of a

single dose of oral ondansetron in facilitating successful rehydration

of under-five children. This study also reported similar efficacy by

demonstrating lesser failure of ORT (31% vs 62%) and lesser need

of intravenous fluids. This study is most probably the first

double–blind randomized placebo controlled trial on this topic from a

developing country. Present study confirms efficacy of single oral dose

of ondansetron on cessation of vomiting, resulting in better oral

rehydration and parents’ satisfaction. At present there is lack of

evidence for repeated doses, use in ambulatory settings, and in children

with malnutrition.

References

1. Fedorowicz Z, Jagannath VA, Carter B.

Anti-emetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis

in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2011;9:CD005506.

2. Carter B, Fedorowicz Z. Anti-emetic treatment

of acute gastroenteritis in children: An updated Cochrane systematic

review with meta-analysis and mixed treatment comparison in a

Bayesian framework. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000622.

3. FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal

heart rhythms may be associated with use of Zofran (ondansetron).

Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm271913.htm. Accessed

January 10, 2015.

Praveen Kumar

Department of Pediatrics , LHMC, New Delhi, India.

Email:

[email protected]

Pediatrician’s Viewpoint

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) has been the

cornerstone of all the diarrhea treatment protocols since 1970s.

However, in this era of indiscriminate use of antibiotics and other

drugs, ORT is being grossly underused. One of the major barriers to ORT

is vomiting which makes pediatricians prefer intravenous fluids many a

times only for parental reassurance. Literature suggests that wealthier

family children are 1.5 times less likely to receive oral rehydration

salt (ORS) solution. Till ORS is made more palatable, we have to rely on

other cost-effective strategies to promote its use.

In this study, the authors have carried out a

systematic randomized controlled trial (RCT), and supported the use of

single dose of ondansetron in acute diarrhea with vomiting for

successful delivery of ORT. However, lack of follow-up to see

readmission rates or assessment for worsening of diarrhea, as reported

in previous studies, has not been done.

In the Indian context, it could be an excellent step

to scale up ORS use as motivating parents and even healthcare providers

to give ORT despite vomiting is not easy, and traditional antiemetics

have been marred with side effects. However, we should resist from a

tendency to jump to this drug as it was originally intended for severe

vomiting in chemotherapy and post-operative patients. More robust

studies are needed to address the concerns of safety and benefit in

ambulatory settings, and in select group of children such as those with

severe malnutrition and other co-morbities.

Shivani Deswal

Department of Pediatrics,

PGIMER, Dr RML Hospital,

New Delhi, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

|

|

|

|