|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2015;52: 149 -150 |

|

Preputial Calculus in a

Neurologically-impaired Child

|

|

RI Spataru, DA Iozsa and M Ivanov

From Department of Pediatric Surgery, Emergency

Clinical Hospital for Children "Maria Sklodowska Curie", University of

Medicine and Pharmacy "Carol Davila" Bucharest, Romania.

Correspondence to: Dr Spataru Radu-Iulian: 20, Bld.

Brancoveanu C., PC 041451, Emergency Clinical Hospital for Children

"Maria Sklodowska Curie", Bucharest, Romania,

Email: [email protected]

Received: July 28, 2014;

Initial review: September 01, 2014;

Accepted: October 09, 2014.

|

|

Background: Preputial calculi are rarely encountered in childhood.

Case characteristics: A 5-year-old boy with symptoms of chronic

balanoposthitis. Observation: A preputial stone was documented

and removed at circumcision. Outcome: Uneventful postoperative

recovery. Message: In children, association between phimosis and

neurologic impairment represent predisposing condition for preputial

stone formation.

Keywords: Children, Phimosis, Prepuce.

|

|

P

reputial calculi are an uncommon entity. It has

been described in isolated case reports, mostly in elderly men, with

tight phimosis and poor hygiene [1-4]. It is postulated that these

calculi originate from inspissated smegma with lime salts trapped into

the phimotic prepuce, infected stagnant urine or migrated calculi from

the upper urinary tract into the preputial sac [1]. Preputial calculi in

children are very rare [5-7] , usually associated with phimosis and

other urologic and/or neurologic anomalies.

Case Report

A 5-year-old-male was referred to our hospital with

the presumed diagnosis of balanoposthitis. The child had paraparesis and

incontinence for urine and feces, following surgery in infancy for

myelomeningocele. The penis looked severely swollen, from the tip almost

to the penoscrotal junction. The foreskin was significantly thickened,

with a tight phimotic ring showing ulceration on its circumference,

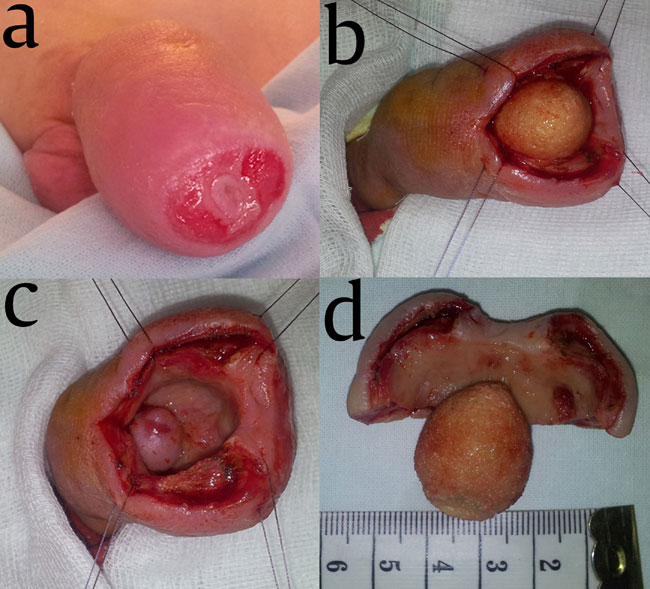

making impossible examination of the meatus opening (Fig. 1a).

No stricture band or hair tourniquet could be found along the penile

shaft or at the base of the penis. Testes and scrotum looked normal.

Significant diaper rash and pressure sores were evident in the inguinal,

perineal and sacral area. No signs of acute urine retention were noted.

The patient presented intermittent leaking urine without an obvious

stream. The patient was diagnosed with chronic balanoposthitis probably

occurring in the context of neurological impairment and tight phimosis.

Bladder catheterization for urine analysis was unsuccessful. A metal

probe was attempted to pass through the foreskin opening when a

presumable foreign body was identified with a hard, stone-like

consistency.

The radiologic examination of the abdomen and pelvis

showed a well-defined, round, radiopaque shadow in the distal penile

region. Ultrasound revealed a bright hyperechoic structure located in

the preputial sac; there were no signs of urolithiasis.

Circumcision was performed (Fig. 1 b-d)

with the removal of a thick preputial sac molded on a 3/2 cm ovalar

calculus with the glans imprint on it, light colored with a rough

surface. Penis had a normal size with an adequate meatus opening. Postop

urethral catheterization showed presence of leukocyte, but negative

urine culture. Postoperative recovery was uneventful. Chemical analysis

of the stone showed calcium oxalate with no foreign bodies found inside.

Serum and urinary levels of electrolytes and uric acid were in normal

ranges; parathyroid hormone level was also normal.

|

|

Fig. 1 (a) Penis severely swollen,

from the tip almost to the penoscrotal junction; tight phimotic

ring showing ulceration on its circumference; (b,c,d) removal of

a thick preputial sac molded on a 3/2 cm ovalar calculus with

the glans imprint on it, light colored with a rough surface.

|

Pathological exam of the prepuce confirmed

balanoposthitis.

Discussion

In the first years of life the prepuce is attached to

the glans by physiological congenital adhesions, so there is a little

room for urine to collect in the preputial sac. There have been

described, in extremely rare cases, congenital giant deep preputial sac

with very large capacity for urine collection [8], which could favor

stone formation. In our case, no such anomaly could be identified.

Scarring of the prepuce with progressive fibrous

phimosis due to chronic pathological conditions such as Balanitis

xerotica obliterans (BXO) usually occurs in older children and adults.

Newly published data has shown a higher incidence than was previously

reported in children under the age of 5, if the diagnosis is based on

histopathological examination at the time of circumcision [9]. Our

histopathological examination was able to exclude BXO as a possible

cause for phimosis.

In adults with neurogenic bladder, 62.5% of

nephroliths were metabolic disease-related [10]. This research

highlights the importance of documenting metabolic disorders in

neurologically-impaired patients with urolithiasis. In children,

preputial stones occur in the presence of phimosis associated with other

urological and/or neurological malformation (e.g. epispadias and

low imperforated anus and myelomeningocele). Neglected preputial stones

may generate serious complications such as bilateral hydronephrosis and

acute renal failure [1], or even penile carcinoma [3]. One case

described in a child showed preputial skin fistula as a consequence of

multiple preputial calculi [7].

In our case, evaluation excluded presence of calculi

anywhere else along the urinary tract, or foreign body as a nucleus, or

signs of present urinary infection. We can assume that the possible

etiology was either migration of a proximal situated micro-calculus,

which developed further in the tight preputial sac or de novo

formation of the calculus in the stagnant urine in the preputial cavity.

In conclusion, preputial calculi can occur in

childhood, association between tight phimosis and urinary incontinence

representing a predisposing circumstance.

Contributors: SR: Conception of the work;

revising paper for important intellectual content; IDA: Analysis and

interpretation of the data for the work; drafting the work; IM:

Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data for the work;

drafting the work and revising it critically for important intellectual

content. All authors approved the final manuscript and take

responsibility for its conent.

Funding: None; Competing interests: None

stated.

References

1. Yuasa T, Kageyama S, Yoshiki T, Okada Y. Preputial

calculi: a case report. Acta Urol Jpn. 2001;47:513-5.

2. Hori N, Hoshina A, Kinoshita N, Kato M, Arima K,

Tajima K, et al. A case of preputial calculi. Acta Urol Jpn.

1985;31:327-9.

3. Mohapatra TP, Kumar S. Concurrent preputial

calculi and penile carcinoma a rare association. Postgrad Med J.

1989;65:256-7.

4. Nagata D, Sasaki S, Umemoto Y, Kohri K. Preputial

calculi. BJU Int. 1999;83:1076-7.

5. Sharma SK. Phimosis and the preputial calculus.

Indian Pediatr. 1983;20:386.

6. Ellis DJ, Siegel AL, Elder JS, Duckett JW.

Preputial calculus: a case report. J Urol. 1986; 136:464-5.

7. Tuğlu D, Yuvanç E, Yilmaz E, Batislam E, Gürer

YKY. Unknown complication of preputial calculi: preputial skin fistula.

Int Urol Nephrol, 2013, July 25, online, DOI 10.1007/s11255-013-0496-x.

8. Philip I, Hull NJL. Congenital giant prepucial

sac: Case reports. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;3: 507-8.

9. Jayakumar S, Antao B, Bevington O, Furness P,

Ninan GK. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children and its incidence

under the age of 5 years. J Pediatr Urol. 2012;8:272-5.

10. Matlaga BR, Kim SC, Watkins SL, Kuo RL, Munch LC,

Lingeman JE. Changing composition of renal calculi in patients with

neurogenic bladder. J Urol. 2006;175: 1716-9.

|

|

|

|

|