|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2015;52: 115 -118 |

|

Effect of Simultaneous

Administration of Oral Polio Vaccine on Local Reaction of BCG

Vaccine in Term Infants

|

|

MMA Faridi and Shitanshu Srivastava

From Department of Pediatrics, Era’s Lucknow Medical

College, Lucknow, UP, India.

Correspondence to: Dr MMA Faridi, E-9 GTB

Hospital, Delhi 110 095, India.

Email: [email protected]

Received: December 30, 2013;

Initial review: February 06, 2014;

Accepted: December 08, 2014.

|

Objective: To study local reaction and to ascertain timing of scar

formation in infants after BCG vaccination at birth, with and without

simultaneous administration of trivalent OPV.

Design: Prospective observational study.

Setting: Teaching hospital in Lucknow, India.

Participants: 152 term neonates born in the

hospital and given BCG and OPV 0-dose simultaneously before discharge,

within 7 days of birth (Group I) , and 122 infants born at home or in

private health facility, not given OPV-0 dose, coming for vaccination

within 7 days of age (Group 2).

Intervention/Observation: Follow up done at 6

week, 10 week, 14 week and 9 months. Local reaction was recorded at the

site of BCG vaccination.

Results: Scar formed in

£14 wks

in 51.3% and 89.3% babies in Group 1 and Group 2, respectively following

BCG vaccination (P<0.001). At 9 months, scar developed in 93.9%

infants in Group I and 94.3% babies in Group II. Abortive reaction and

non-reactors were similar in both groups (P>0.05).

Conclusions: Simultaneous administration of BCG

vaccine with trivalent OPV to term infants in early neonatal period

prolongs the time of scar formation but sequence of local reaction is

not affected.

Keywords: Abortive reaction, BCG, Immunization, Neonate, OPV,

Scar.

|

|

B

CG is routinely administered to all newborn

infants under the Universal Immunization Program. Oral Polio Vaccine

(OPV) is recommended at birth together with BCG vaccine for all

institutional deliveries [1]. Local reaction at the BCG vaccination site

is described as papule, pustule, ulcer, scab, scar and abortive

reaction; it may take 10 weeks to 6 months or more to form a scar [2].

Administering OPV together with BCG might down- regulate the response to

BCG vaccine [3]. The present study was planned to observe local reaction

and time of scar formation in term appropriate-for-gestation age (AGA)

infants, following BCG vaccination within 7 days of birth with or

without simultaneous administration of trivalent OPV.

Methods

The present study was conducted in the Department of

Pediatrics, Era’s Medical College and Hospital, Lucknow, India during

March 2008 to December 2010 after taking approval from the Institutional

Ethics Committee and informed consent from parents. All consecutive term

AGA babies [5] of both sexes born in the hospital with birth weight

2.2-4 kg were recruited. Consecutive neonates who were not delivered in

the study hospital but came for vaccination within 7 days of birth were

screened by history and available investigation reports done in the

antenatal period, and were included if they fulfilled inclusion

criteria. Infants having contact with tuberculosis patient or those born

to mothers suffering from tuberculosis, severe anemia, diabetes,

HIV/AIDS or Hepatitis B and those admitted in the neonatal intensive

care unit for sepsis, intrauterine infection, jaundice, perinatal

asphyxia, congenital malformation or suspected chromosomal anomalies,

and family residing more than 10 km away from the hospital were excluded

from the study.

The institution protocol is to discharge normal

parturient mothers and their babies after 48 hours of birth; in case of

Lower Segment Cesarean Section (LSCS) a mother is discharged on day 5-6

after removing abdominal stitches. BCG vaccine is given only on

Thursdays; rest of the vaccines are administered on all working days.

Therefore, BCG and OPV-0 dose cannot be administered simultaneously to

all infants before discharge from the hospital. In home-delivered

infants, the BCG vaccination is advised within 2 weeks but OPV 0-dose is

not recommended to them under National Immunization Schedule. The study

subjects thus were divided in two groups: Group I: Infants born in the

study hospital and received BCG and OPV 0-dose simultaneously within 7

days of age before discharge; and Group II: Babies born at home or in a

private health facility, who did not receive either OPV-0 dose or Pulse

Polio Program dose, and came to study hospital for immunization within 7

days of age. Only BCG vaccine was given to them.

All mothers were counseled for exclusive

breastfeeding by a nurse or faculty trained in infant and young child

feeding counseling at the time of discharge [6]. They were also

counseled for regular follow-ups and immunization on subsequent visits

as per National Immunization Schedule.

One trained staff nurse with more than 5 years of

experience in the immunization clinic administered 0.1 mL of BCG vaccine

(Danish 1331 strain; BCG laboratory, Guindy Chennai) to all enrolled

babies. The freeze-dried vaccine was reconstituted with normal saline

and given intradermal on the left arm just above the insertion of the

deltoid muscle with a 26-gauge needle and tuberculin syringe to produce

a wheal of 5 mm. The reconstituted vaccine was used within 4 hours and

then discarded. Cold chain was maintained and monitored as per standard

protocol. Oral trivalent polio vaccine Sabin strain (Bharat Biotech) was

administered to babies in Group I simultaneously with BCG. OPV was not

administered to infants belonging to Group II. Cold chain was maintained

and vaccine viability was checked with the help of vaccine vial monitor.

Four follow-ups were done at 6 (+1) week, 10 (+1)

week, 14 (+1 week) and 9 months (+2 weeks). The local reaction at the

vaccination site was recorded as papule, pustule, ulcer, scab, scar, no

reaction, and abortive reaction [2]. Babies who did not have any

reaction at the inoculation site at 14 weeks were labeled as

non-reactor. Infants who did not develop scar by 14 weeks but had

papule, pustule or ulcer were counseled for follow-up at 9 months. Local

reaction was recorded by a single observer in all subjects. If there was

any ambiguity, both authors concurred for abortive reaction or no

reaction.

Statistical analyses: The data were entered in

Microsoft Excel and checked for any inconsistency. Univariate logistic

regression analysis was carried out to find out any relationship of scar

formation at 6, 10, 14 weeks and 9 months with sex and birth weight of

the infants. P-value <0.05 was considered as significant.

Analysis was carried out with SPSS Version 16.0.

Results

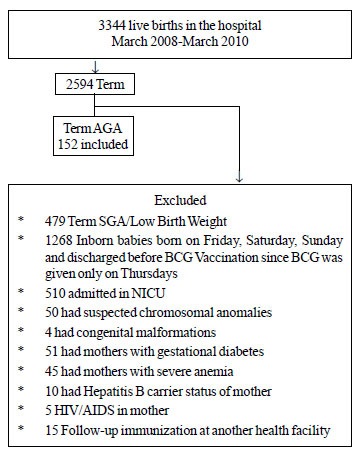

Out of 275 babies recruited (Fig. 1),

Group I comprised of 152 consecutive neonates. Four of these infants

were lost to follow-up and 148 infants were included for analysis. Group

II comprised of 123 neonates, who received only BCG. One child was lost

to follow-up due to change of residence as per telephonic conversation.

Hence, data of 122 infants were analyzed.

|

|

Fig. 1 Recruitment flow of

participants

|

Number of infants delivered normally, with the help

of forceps and by LSCS, socioeconomic status of the parents and clinical

profile of the mothers such as hemoglobin level, parity and antenatal

check-up status were comparable in both groups. The mean (SD) birth

weight of babies in Group I [2.73(0.30 kg)] and Group II [2.75 (0.32

kg)] was comparable (P=0.57). The mean age of infants at

immunization was 2.6 days (range 1-6 days) and 3.9 days (range 2-7 days)

in Group I and II, respectively. Both groups were sex- and age-matched.

Sex and birth weight of the infants did not affect either the

development of local reaction or time of scar formation in both groups.

The advent and sequence of local reaction was similar

in both groups at 6, 10 and 14 weeks following BCG vaccination (Table

I). A higher (P<0.01) proportion of infants deceloped scar at

6 weeks in Group II infants (25.4%), in comparison to infants of Group I

(3.4%).

TABLE I Local BCG Reaction in Group I (BCG and OPV0 dose) and Group II (only BCG) Infants

|

Local Reaction |

6 wks

Group |

10 wks

Group |

14 wks

Group |

9 months

Group |

|

I No. (%) |

II No. (%) |

I No. (%) |

II No. (%) |

I No. (%) |

II No. (%) |

I No. (%) |

II No. (%) |

|

Induration |

30(20.3) |

5(4.1) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Papule |

54(36.5) |

13(10.7) |

14(9.5) |

5(4.1) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pustule |

39(26.4) |

28(22.9) |

43(29.1) |

3(2.5) |

10(6.8) |

1 (0.8) |

0 |

0 |

|

Ulcer |

10(6.8) |

33(27.0) |

30(20.3) |

18(14.8) |

20(13.5) |

4 (3.3) |

0 |

0 |

|

Scab |

0(0.0) |

7(5.7) |

35(23.6) |

2(1.6) |

33(22.3) |

1 (0.8) |

0 |

0 |

|

No reaction |

10(6.8) |

5(4.1) |

8(5.4) |

4(3.3) |

5(3.4) |

4 (3.3) |

5 (3.4) |

4 (3.3) |

|

Abortive reaction |

|

|

|

|

4(2.7) |

3 (2.5) |

4 (2.7) |

3 (2.5) |

|

N= 148 in Group I and 122 in Group II. |

Table II depicts the comparison of scar

formation between infants of Group I and II. The development of scar was

significantly lower among Group I as compared to Group II infants till

14 weeks post-vaccination. The cutaneous reaction at the site of BCG

immunization in the form of either scar or abortive reaction was similar

(96.6% vs 96.8%) in both groups.

TABLE II Comparison of Scar Formation in Two Groups

|

Reaction |

6 wks

Group |

10 wks

Group |

14 wks

Group |

9 months

Group |

|

I No. (%) |

II No. (%) |

I No. (%) |

II No. (%) |

I No. (%) |

II No. (%) |

I No. (%) |

II No. (%) |

|

Scar |

5(3.4) |

31(25.4) |

18(12.1) |

90(73.7) |

76(51.3) |

109(89.3) |

139(93.9) |

115(94.3) |

|

No scar |

143(96.6) |

91(74.6) |

130(87.8) |

32(26.2) |

72(48.6) |

13(10.7) |

9(6.1) |

7(5.7) |

|

OR (95% CI), |

0.10 (0.04-0.27) |

0.05 (0.03-0.09) |

0.13 (0.07-0.24) |

0.94 (0.34-2.60) |

|

P value |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

0.91 |

|

*Derived by univariate logistic regressionN = 148 in Group I

and 122 in Group II. |

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that simultaneous

administration of OPV with BCG vaccine at birth may affect local BCG

reaction. The sequence of cutaneous reaction, incidence of abortive

reaction and number of non-reactors were similar in infants given BCG

and OPV together and those who received BCG vaccine alone. However, scar

formation lagged behind at 6, 10, and 14 weeks post-immunization in

infants who received both BCG and OPV together. Eventually scar formed

by 9 months in all infants at the site of BCG inoculation.

Interaction between the two live vaccines, BCG and

OPV, administered simultaneously at birth, was studied by the

development of local cutaneous reaction but effect on in vivo

immune response was not studied by us. The other limitations were

non-randomized design of study, and no blinding of investigators.

OPV is widely administered along with BCG at birth in

developing countries but little is known regarding the adverse impact on

cellular immune responses following vaccination [4]. The development of

scar at the site of BCG vaccination is regarded as an evidence of

successful vaccination [3,7-8] and may be taken as a surrogate marker

for development of immunogenicity [9,10]. It has been reported that the

scar forms in 65.3% to 100% infants following BCG vaccination (7-14). In

all these studies, OPV was not administered simultaneously with BCG

vaccine. Kaur, et al [3]. opined that BCG and OPV given together

at birth might delay scar formation by 3 months of age [3]. Sartono,

et al. [4] demonstrated that mucosal administration of OPV

simultaneously with intradermal BCG vaccination at birth may have

profound immunological consequences. They reported that this may down-

regulate response to BCG in the form of fewer numbers of scar formation,

reduced scar size, reduced in vivo response to purified protein

derivative (PPD) and significantly lower IL-13 and IFN- g

and a tendency to have lower IL-10 in response to PPD at 6 weeks

following immunization [4]. Jensen, et al. [15] in a recent study

have also shown that giving OPV and BCG together to neonates led to

significantly lower prevalence of IFN-g

and reduced levels of interleukin-5 to PPD, implying that OPV affected

both Th-1 and Th-2 cytokine responses. Most BCG efficacy studies were

done prior to the introduction of OPV at birth. It may be speculated

that the addition of OPV to BCG at birth has further compromised the

protection induced by BCG [4]. After BCG vaccination, a cascade of

reaction takes place where IL-2, interferon-g

and TNF-a are

predominantly secreted. Inflammation and suppuration at the site of BCG

vaccination are mediated through interleukins [16]. Which of these

reaction/s or cascade is affected by OPV, if administered

simultaneously, at the time of BCG vaccination is an area of research.

We conclude that simultaneous administration of OPV

with BCG vaccine delays scar formation, but it does not affect

sequential development of the local reaction or proportion of

non-reactors.

Contributors: Both authors participated in study

design, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing.

Funding; None; Competing interests: None

stated.

|

What Is Already Known?

•

The formation of scar at the site of BCG vaccination is

regarded as an evidence of successful immunization.

What This Study Adds?

•

Simultaneous

administration of BCG and OPV at birth prolongs the time of scar

formation.

|

References

1. Yewale V, Choudhary P, Thackar N, editors. IAP

Guide Book on Immunization. IAP Committee on Immunization 2009-2011. p.

47-52.

2. Faridi MMA, Krishnamurthy S. Abortive reaction and

time of scar formation after BCG vaccination. Vaccine.

2008;17:26:289-90.

3. Kaur S, Faridi MMA, Agarwal KN. BCG vaccination

reaction in low birth weight infants. Indian J Med Res. 2002;116:64-9.

4. Sartono E, Lisse IM, Terveer EM, Van de Sande

PJM, Whittle H, Fisker AB, et al. Oral polio vaccine influences

the immune response to BCG vaccination. PLoS One. 2010;5: e10328.

5. Lubchenco LO, Hansman C, Dressler M, Boyd E.

Intrauterine growth as estimated from live born birth weight data at 24

to 42 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 1963;32:793-800.

6. Infant and Young Child Feeding Counseling: A

Training Course: The 3 in 1 course-2008 Version (An Integrated Course on

Breastfeeding, Complementary feeding and Infant Feeding & HIV –

Counseling). Breastfeeding Promotion Network of India and IBFAN Asia.

7. Seth V, Kabra SK. BCG Vaccination. In:

Essentials of Tuberculosis in Children, 3rd Ed; 2006; p. 597-620.

8. Thayyil-sudan S, Kumar A, Singh M, Paul VK,

Deorari AK. Safety and efficacy of BCG vaccination in preterm babies.

Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:F-646.

9. Gupta P, Faridi MMA, Shah D, Dev G. BCG reaction

in twin newborns: Effect of zygosity and chorionicity. Indian Pediatr.

2008;45:271-7.

10. Ahmad S, Javid I. Absence of scar formation in

infants after BCG vaccination. Professional Med J. 2006;13:637-41.

11. Lakhar BB. Neonatal BCG vaccination and scar

success. Indian Pediatr. 1995; 32:1323.

12. Joshi S. BCG vaccination (immunization dialogue).

Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:332-3.

13. Sedaghatian M, Hashaem F, Hossain MM. Bacillus

Calmette-Guerin vaccination in preterm infants. Int J Tuber Lung

Dis.1998;2:679-82.

14. Fine PEM, Ponnighaus JM, Maine N. The

distribution and implication of BCG scar in Northern Malawi. Bull

World Health Organ. 1989;67:35-42.

15. Jensen KJ, Karkov HS, Lund N, Andersen A, Eriksen

HB, Barbosa AG, et al. The immunological effects of oral polio

vaccine provided with BCG vaccine at birth: A randomised trial. Vaccine.

2014;32:5949-56.

16. Sallusto F, Lenig D, Förster R, Lipp M,

Lanzavecchia A.Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing

potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708-12.

|

|

|

|

|