Sandip Bartakke, S.B. Bavdekar, Pratima Kondurkar,

Mamta N. Muranjan, Mamata V. Manglani* and Ratna Sharma*

From the Department of Pediatrics, Seth G.S. Medical

College and KEM Hospital and *Division of Pediatric

Hematology-Oncology, L.T.M. Medical College and L.T.M. General

Hospital.

Mumbai, India.

Correspondence to: Dr. S.B. Bavdekar, A2-9, Worli

Seaside CHS, Pujari Nagar, KAG Khan Road, Worli, Mumbai 400 018,

India. E-mail:

[email protected]

Manuscript received: June 24, 2003, Initial review

completed: October 27, 2003;

Revision accepted: September 6, 2004.

.

Abstract:

A prospective multi-centric study was

conducted to determine if iron-chelating agent deferiprone also

chelates zinc. Twenty four-hour urinary zinc levels were

compared in multiply transfused children with thalassemia major

not receiving any chelation therapy (Group A, n = 28), those

receiving deferiprone (Group B, n = 30) and age and sex-matched

controls of subjects in Group B (Group C, n = 29) by a

colorimetric method. The 24-hour mean urinary excretion of zinc

was significantly higher in Group B (1010.8 ± 1248.1 mcg) than

in the other two groups (Group A: 547.8 ± 832.9mcg and Group C

459.8 ± 270.3mcg) indicating that deferiprone chelates zinc.

Keywords: Adverse event, Chelation, Hemosiderosis, Iron.

Beta thalassemia is one of the most common

genetic defects seen in certain populations(1). Thalassemia major

represents the life threatening variety of this disorder wherein

the child’s life depends upon receipt of regular red cell

transfusions. Chronic iron overload leading to organ dysfunction

involving the heart, liver and endocrine glands is the logical

consequence of life-long transfusion therapy(2).

Chelation therapy with desferrioxamine (deferoxamine)

helps avert iron overload(3). However, the drug has to be

administered as a subcutaneous infusion 5-6 days a week. Cost of

therapy and need to administer it as an injection make many

families reluctant in initiating chelation therapy. Deferiprone

(L1 or 1, 2-dimethyl-3-hydxoxypyridin-4-one), the only oral

iron-chelating drug cleared for clinical use, is primarily being

prescribed in the developing countries. Although the drug

deferiprone offers an affordable option to children with

thalassemia major in developing countries, it is imperative that

investigators continue to study the drug. Gastrointestinal

disturbances, arthralgia, agranulocytosis and raised levels of

transaminases in the liver are some of its known side effects(4).

Being a chelator of iron, it is possible that the drug may also

chelate other metallic ions. Zinc is one of the important elements

that play an extensive role in various body functions. However,

limited information is available regarding the effect of

deferiprone adminis-tration on zinc status. Hence, the present

study was undertaken to determine the effect of deferiprone

therapy on urinary excretion of zinc.

Subjects and Methods

This prospective study was conducted at two

large tertiary care hospitals in Mumbai over a period of one year.

The institutional ethics committee endorsed the study protocol.

Multiply transfused children diagnosed to have thalassemia major

on the basis of clinical presentation, dependence on blood

transfusion and hemoglobin electrophoresis report were enrolled in

the study after obtaining an informed consent from the guardians.

Those not receiving any chelation therapy were included in Group A

while those receiving deferiprone were enrolled in Group B. In

addition, the age-and sex-matched children without thalassemia

major and not receiving any transfusion therapy were included in

the study as controls (Group C) after following a similar

procedure for obtaining the consent from the guardians. The

controls were also matched for the nutritional status. The data

regarding age at diagnosis, duration of transfusion therapy,

yearly trans-fusion requirements (transfusion required in the last

12 months), results of the liver function tests (plasma levels of

hepatic transaminases and protein), serum ferritin levels and the

dose and duration of deferiprone therapy was collected by review

of records. The nutritional status was deter-mined and the grade

of malnutrition was judged using the classification provided by

the Indian Academy of Pediatrics(5).

Two mL of venous blood was collected from

subjects using heparin as anticoagulant. The sample was

centrifuged and plasma was separated. Twenty-four hour, urine was

collected by patients at home in a zinc-free container. The volume

of the urine was measured in the laboratory. Samples of plasma and

urine were stored in the refrigerator at 2şc to 8şC and

determination of zinc levels in these samples was done in batches

of five samples. The laboratory technician who performed the assay

was unaware of the groups to which the subjects belonged. Zinc

level was estimated using a colorimetric method(6) using a kit

provided by Randox Laboratories. Comparison of a variable between

different groups was deter-mined using Student’s "t" test.

Correlation of different variables in a single group was done by

using coefficient of correlation.

Results

Eighty seven subjects (55 boys and 32 girls, M

: F = 1.6) were enrolled in the study that included 28 children in

Group A, 30 in Group B and 29 in Group C. As shown in Table I, the

three groups were comparable in terms of age and state of

malnutrition. Fifteen (50%) children in Group B were on

deferiprone for only 3-6 months, six were receiving the drug for

7-12 months while another 9 (30%) were on chelation therapy for

over 12 months. As shown in Table 1, the 24-hour urinary excretion

of zinc was significantly higher in children receiving deferiprone

(Group B, 1010.8 ± 1248.1 mcg) than in the other two groups.

Children with thalassemia major who were receiving regular

transfusion therapy, but were not receiving any chelation therapy

(Group A) did not show significantly high urinary zinc excretion

(547.8 ± 832.9 mcg/24 hr) as compared to the controls (Group C,

459.8 ± 270.3; P >0.05).

TABLE I

Demographic Characteristics, 24-hour Urinary Zinc Excretion and Plasma Zinc Levels.

|

Characteristics |

Group A |

Group B |

Group C |

Children with thalassemia major on

Regular transfusion therapy |

Controls |

Without chelation

therapy |

On deferiprone

|

|

Age (Mean ± SD; years) |

7.2 ± 2.5* |

7.9 ±3.4* |

7.2 ±2.9* |

|

Male: female ratio |

1.3:1 |

2: 1 |

1.9 : 1 |

|

Median grade of malnutrition |

II |

II |

II |

|

24-hr urinary zinc excretion (µg/24

hrs) |

547.8 ±832.9** |

1010.8 ±1248.1**# |

459.8 ±270.3# |

|

Plasma zinc level (µmol/L) |

8.0 ±5.8 |

7.5 ±6.0 |

9.5 ±3.8 |

*P > 0.05, ** P< 0.01; #: P<0.001.

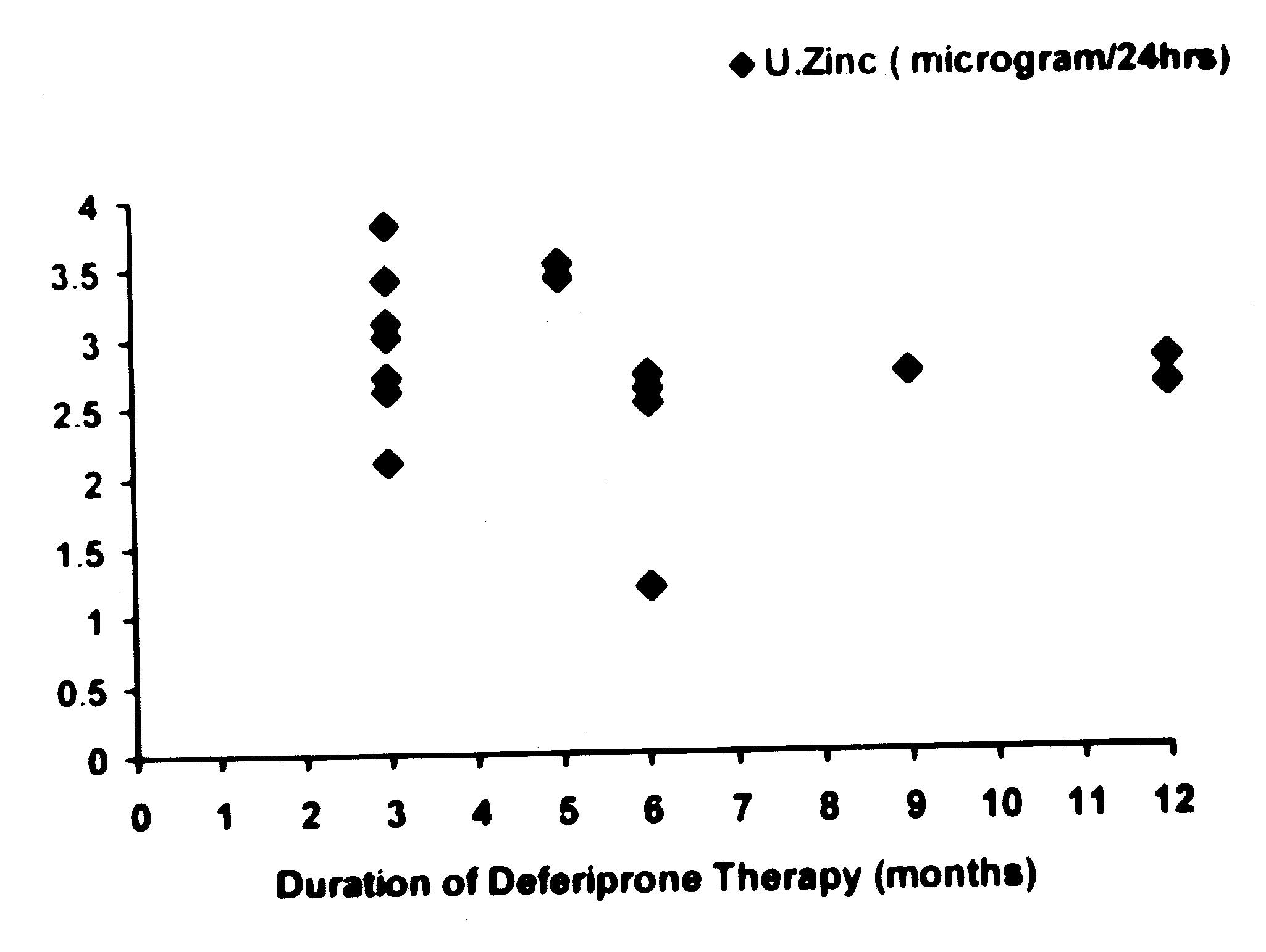

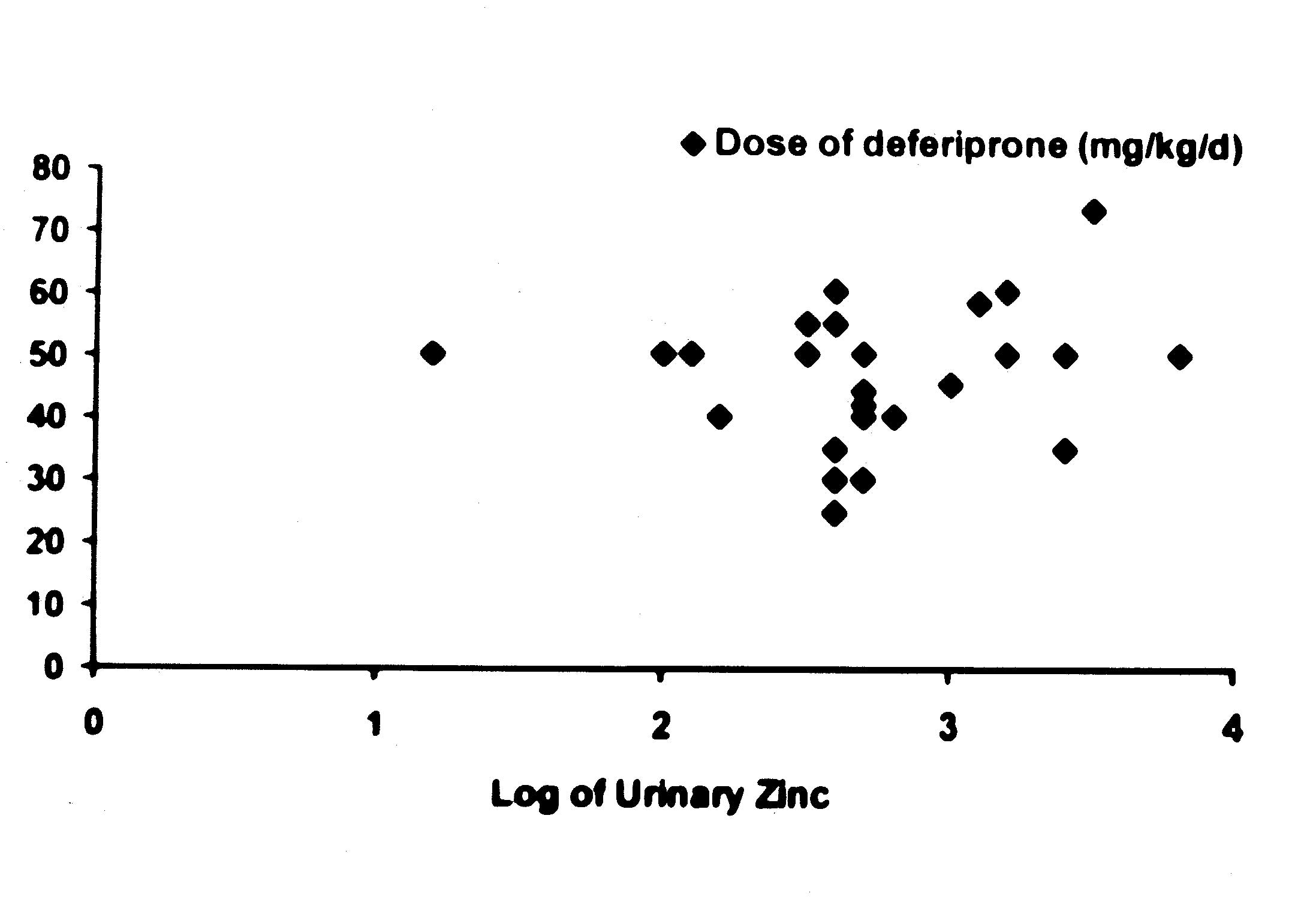

An attempt was made to determine if the urinary

excretion of zinc was related to the duration and dose of

deferiprone in the patients belonging to the Group B (Figs. l and

2). As the range of values for 24-hour urinary zinc excretion were

too wide, log of these values were compared with the duration and

dose of deferiprone therapy. It was noted that there was no

correlation between duration (r = – 0.26, P <0.05) and dose (r =

0.19, P <0.05) of deferiprone and (log of) urinary zinc levels.

Although plasma zinc levels in Group B were found to be lower than

those in other groups, the difference was not statistically

significant (P >0.05). However, it is noteworthy that the levels

in all the three groups were significantly lower than the

reference values(6).

|

|

| Fig. 1.

Relationship between the duration of deferiprone therapy and

urinary zinc excretion. |

Fig. 2.

Relationship between the dose of deferiprone and urinary

zinc excretion.

|

Discussion

A few studies have indicated that deferiprone

may, in addition to iron, chelate zinc as well. This is an

important issue since zinc plays an important role in several

physiological functions; protein synthesis, gene expression,

immunity, wound healing amd maintenance of integrity of

intra-cellular organelles(7). In addition, it has been recently

noted that deferiprone therapy is associated with zinc depletion

in thymocytes(8).

The present study demonstrated that urinary

zinc levels in children on deferiprone were significantly higher

than those in controls as well as in children with thalas-semia

who were not receiving deferiprone. This unequivocally proves that

the drug chelates zinc and it is not the "thalassemic state" that

is responsible for excessive zinc excretion. The study did not

demonstrate any significant relationship between dose of

deferiprone and duration of chelation therapy and urinary zinc

excretion. Al Refaie, et al.(9) also did not find correlation

between the dose of deferiprone and the extent of urinary zinc

excretion. It is possible that long-term deferiprone therapy

depletes total body zinc and therefore, urinary zinc excretion may

not increase any further or may, in fact, show a decline from the

baseline when the body zinc stores have been significantly

depleted.

The failure of the present study to demonstrate

this relationship may be due to the fact that up to 50% of our

subjects in Group B were receiving deferiprone for a short period

of 3-6 months. This may also account for the inability of the

study to demonstrate significantly lower plasma levelsof zinc in

patients receiving deferiprone.

Despite certain limitations, the findings

obtained from the study have definite implications. Deferiprone

chelates zinc and hence, with long-term use is likely to result in

depletion of body zinc. Cohen, et al.(4) and Al-Refaie, et al.(9)

have already shown that deferi-prone therapy results in low zinc

levels in the blood. Therefore, it may be prudent to start zinc

supplementation to avoid the occurrence of negative zinc balance.

This is probably more relevant in Indian children as they are

known to have zinc levels that are lower than reference

values(10).

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Nilima Kshirsagar, Dean,

Seth G.S. Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai for permitting

the authors to publish this study.

Contributors: SB data collection, statistical

analysis, providing first draft; SBB involved in

conceptualization, designing of the study, editing drafts, will

act as guarantor; PK performed technical and laboratory tests; MNM

supervision over data collection, edited drafts; MVM: assisted in

designing and coordinating the study, edited drafts; RS:

supervision over data collection, assisted in literature review,

edited drafts.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

|

Key

Messages |

• Administration of deferiprone is associated with an increase

in the urinary excretion of zinc.

• Further research is warranted on the need to provide zinc

supplementation to children receiving deferiprone for a longer

duration.

|

|

|

1. Indian Council of Medical Research.

Multicentric study to determine b-thalassemia carrier rate

in school children in Bombay, Calcutta and Delhi, New Delhi,

Indian Council of Medical Research 1991.

2. Edward JB, Patricia JVG. Thalassemia

Syndromes. In: Miller DR, Robert LB (Eds.) Blood Diseases of

Infancy and Childhood, 7th edition, St. Louis; Mosby;

1990,460-498.

3. Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM.

Iron-chelating therapy and the treatment of thalassemia.

Blood 1997; 89: 739-761.

4. Cohen AR, Galanello R, Piga A, Dipalma

A, Vullo C, Tricta F. Safety profile of the oral chelator

deferiprone: A multi-centre study. Br J Hematol 2000; 108:

305-312.

5. Nutrition subcommittee of the Indian

Academy of Pediatrics. Report. Indian Pediatrics 1972, 9:

360.

6. Makino T, Saito M, Horiguchi D, Kina

K. A highly sensitive colorimetric determination of serum

zinc using water soluble pyridylazo dye. Clinical Chimica

Acta 1982; 120: 127- 135.

7. Hipolito VN, Ananda SP. Vitamins &

Trace elements In: Alex CS, Leonard J (Eds.) Gradwohl’s

Clinical Laboratory Methods and Diagnosis. 8th edition, St.

Louis; The C.V. Mosby Company. 1980; p. 376-378.

8. Maclean KH, Cleveland JL, Porter JB.

Cellular zinc content is a major determinant of iron

chelator-induced apoptosis of thymocytes. Blood 2001; 13:

3831-3839.

9. Al-Refaie FN, Wonke B, Hoffbrand AV,

Wickens DG, Nortey P, Kontoghiorghes GJ. Efficacy and

possible adverse effects of the oral iron chelator 1,2

dimethyl 3-hydroxypyrid- 4- one (Ll) in thalassemia major.

Blood 1992; 80: 593-599.

10. Lahiri K, Kher A, Rathi S. Zinc: In Health and

Disease. In: Gupte S. (Ed.) Recent Advances in pediatrics.

Special Volume Nutrition, Growth and Development. New Delhi:

Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 1997. p. 287-

298.

.

|