|

|

|

Indian Pediatr 2020;57:

1172-1176 |

|

What Is New in the Management of Childhood Tuberculosis

in 2020?

|

|

Varinder Singh 1 and Ankit

Parakh2

From 1Department of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical College and

Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital; and 2Pediatric Pulmonology and Sleep

Medicine, BL Kapur Memorial Hospital; New Delhi, India.

Correspondence to: Dr Varinder Singh, Director-Professor, Department

of Pediatrics, Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran

Children’s Hospital, New Delhi 110 001, India.

Email: [email protected]

|

|

The Government of India has developed

a National Strategic Plan for tuberculosis (TB) elimination by 2025,

five years ahead of the global target set by the World Health

Organization (WHO). For achieving these targets there has been a

paradigm shift in the diagnostic and treatment strategies of TB at all

ages. This update summarizes the specific changes in pediatric TB

management in light of the guidelines developed by National Tuberculosis

Elimination Program and Indian of Academy of Pediatrics.

Keywords: Diagnosis, End TB

strategy, National strategic plan, National Tuberculosis Elimination

Program.

|

|

W orld Health Organization (WHO)

announced the End TB strategy with the target of reducing tuberculosis

(TB) deaths by 90% and 95%, and, incidence by 80% and 90%, by 2030 and

2035, respectively [1]. However, Government of India has decided to aim

TB elimination from our country by 2025, ahead of the global target [2].

Childhood TB is an important area of intervention while drawing the

road-map to end TB. National Tuberculosis Elimination Program (NTEP) and

Indian of Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) have partnered to develop updated

guidelines and training program for management of childhood TB in the

country. The salient updates are detailed below.

NEW PARADIGM OF TB DIAGNOSIS

There is a paradigm shift in diagnostic strategy from

conventional smear microscopy to molecular methods of diagnosis due to

their higher sensitivity. NTEP approved rapid nucleic acid amplification

tests (NAAT) like Xpert Rif/Truenat

have made it possible to detect Mycobac-terium

tuberculosis (MTb) with much higher sensitivity as compared to smear

and rapidity than culture. The testing turnaround time for rapid NAAT is

2 hours. These tests are also nested for establishing rifampicin

resistance - a surrogate for multi-drug resistant (MDR) TB.

In addition, NTEP also recommends Line probe assays

(LPA) – which are multiplex NAAT- to test for resistance to rifampicin,

isoniazid and other second line drugs (flouroquinolones and second line

injectables). Unlike rapid NAAT, LPA due to its relatively lower

sensitivity can be used directly only in smear positive specimens or

else after isolating MTb on culture, and has a turnaround time of 3-4

days.

So, TB diagnostics have now graduated to upfront

testing every likely patient for presence of MTb as well as rifampicin

resistance under the strategy called universal drug sensitivity testing

(U-DST) [3].

How Does It Impact the Diagnosis of TB in Children?

Conventional TB diagnostics for children involved

appropriate use of clinical details, chest radiology and tuberculin skin

test, with much less focus on micro-biology, due to poor yield (AFB

smear) or access issues (MTb cultures). U-DST strategy has led to change

in the diagnostic pathways to include NAAT for every patient where a

biological specimen can be procured. Routine chest imaging is done as

initial screening test as testing of respiratory specimens from

radiologically positive cases improves the yield of NAAT [4,5].

While NAAT has higher sensitivity than the smear, yet

it fails in many paucibacillary cases. It is good only as a ‘rule in’

test and a negative NAAT does not rule out TB. The conventional methods

of clinical diagnosis still need to be relied upon among those who are

not confirmed by molecular tests. Current algorithm for evaluation of a

child with pulmonary TB is shown in Fig. 1.

MANAGEMENT OF CHILDHOOD TB

What Is New in Treatment?

Treatment of TB has also evolved from erstwhile

standard regimens based on the likely risk of drug resistance (new

versus retreatment cases) to regimens based on identification of key

resistance. The evidence available earlier in 70s suggested that the

retreatment cases could be treated with a simpler 5 drug category II

regimen. However, post implementation operational research and

meta-analysis showed that this strategy was associated with increased

risk of treatment failure with amplification of resistance to other

companion drugs, particularly, if the patient was initially harboring

rifampicin resistance [3,6]. With the feasibility of upfront rapid

testing for rifampicin resistance, use of standard regimens without

sensitivity testing is no more recom-mended for both the new as well as

retreatment cases.

Likewise, the non-responders to initial regimen for

drug sensitive TB (by 4 weeks) should be assessed again for presence of

drug resistance (rifampicin and isoniazid at least). Non responsive

cases with resistance to rifampicin and/or isoniazid are also tested for

resistance to second line drugs like fluoroquinolones and the injectable

aminoglycosides to provide the most suited regimens depending on the

resistance pattern. The effort is to manage the cases as per the

sensitivity to key drugs, thus improving outcomes and preventing further

ampli-fication of drug resistance. Retreatment cases with-out rifampicin

resistance are now treated again with initial 4 drug regime while being

tested for isoniazid resistance. In case of isoniazid (mono- or poly-)

resistance, 6 month uniphasic 4 drug regime, where isoniazid is replaced

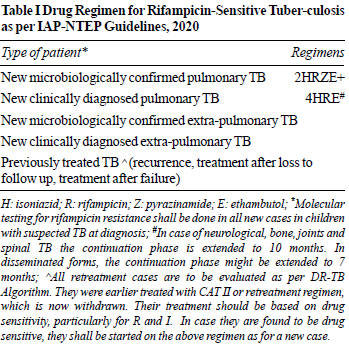

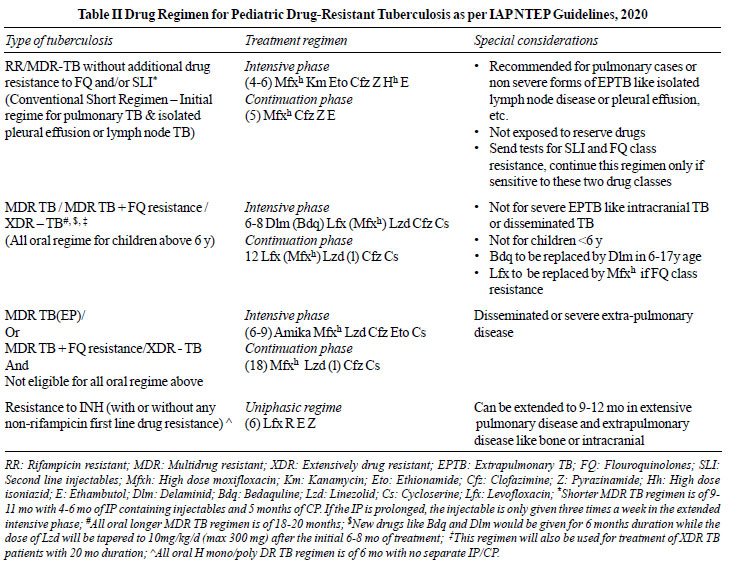

by levofloxacin, is recommended. The IAP NTEP 2020 TB treatment

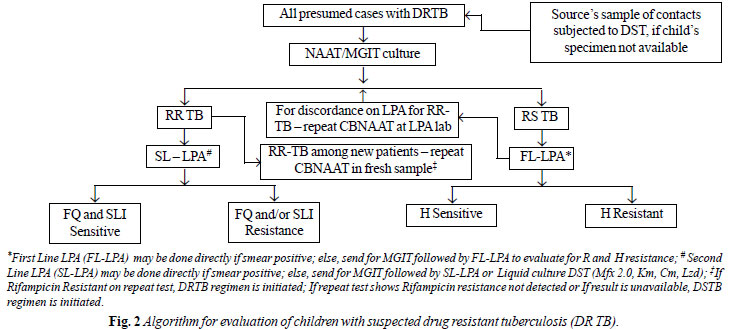

guidelines are shown in Table I and II. The

algorithm for evaluation of children with suspected drug resistance is

shown in Fig. 2.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|

What Else Is New in Management?

NTEP has introduced daily therapy with dispersible

tablets in fixed dose combinations (FDC) for children. Younger children

get 3-drug FDCs (HRZ) along with 100 mg ethambutol tablets. Older

children can also get, in addition, 4-drug FDCs (RHZE) to meet their

drug dosages (Table III). Isoniazid and rifampicin are in

a ratio of 2:3 and the average dose of isoniazid is around 10 mg/kg/day.

These drugs are given free of cost in public sector and the private

sector can also access these drugs for free through various partnership

schemes that the program offers.

Table III Tuberculosis Drug Formulations and Dosages for Children As per IAP NTEP Guidelines, 2020

| Weight band (kg) |

Dose from 0-18 y* |

| 4-7 |

1P + 1E |

| 8-11 |

2P + 2E |

| 12-15 |

3P + 3E |

| 16-24 |

4P + 4E |

| 25-29 |

3P+3E+1A |

| 30-39 |

2P+2E+2A |

|

H-Isoniazid, R-Rifampicin; Z-Pyrazinamide, E-Ethambutol;

*number preceding the letter denotes number of pediatric or

adult formulations; IAP: Indian Academy of Pediatrics; NTEP:

National Tuberculosis Elimination Program; Pediatric formulation

(P) H50, R75, Z150 + E 100 (E separate tab); adult formulation

(A) H75, R150, Z400, E275; Children (aged 0-18 y)

upto the weight of 39 kg should be managed as per this table;

children (aged 0-18 y) ³40 kg would be managed as per the

various weight bands described for adults. |

Experts now also recommend addition of pyridoxine (10

mg/day) with isoniazid containing regimens because of the risk of

peripheral neuropathy due to higher dosages of isoniazid and high

prevalence of malnutrition amongst the affected.

Current Status of Preventive Treatment

Goal to eliminate TB cannot be achieved timely unless

the pool of cases with latent infection is treated. TB preventive

treatment may now be extended to all household contacts of an infectious

case after ruling out disease by symptom screening in line with WHO

guidance. For children above 5 years, if facilities exist, one may test

for presence of latent infection and then treat. But it is not mandatory

to test for infection due to lack of simple and affordable point of care

tests. TB preventive treatment is also recommended for any tuberculin

skin test positive child who is receiving immunosuppressive therapy

(children with nephrotic syndrome, acute leukemia, etc.), and a

child born to mother who was diagnosed to have TB in pregnancy but has

no evidence of disease [7].

Isoniazid is recommended for TB preventive treatment

at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day for six months. No drugs are currently

recommended for TB preventive therapy for the contacts of MDR TB cases

but a close follow up for two years after exposure is recommended for

timely identification of those developing disease among exposed [8].

To conclude, the management of TB in children now has

undergone a sea change with drug sensitivity directed therapy becoming

the corner pillar. NTEP approved rapid NAAT has become the core

investigative modality and erstwhile clinic-radiological approach of

diagnosis is used only when NAAT fails in a clinically probable case.

The pediatricians need also to be aware of the updated guidelines

detailing change in regimens and drug dosages so that they can

rationally manage TB among children.

Contributors: Both authors contributed to

reviewing the literature, drafting, correcting and finalizing the

manuscript.

Funding: None; Competing interest: None

stated.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy.

WHO; 2015.

2. Ministry of Health with Family Welfare. National

Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis: 2017-25. Revised National Tuberculosis

Control Programme. March 2017. Accessed September 16, 2020. Available

from: https://tbcindia. gov.in/WriteReadData/National%20Strategic

%20Plan% 202017-25.pdf

3. Central TB Division, Ministry of Health with

Family Welfare. Technical and Operational Guidelines for TB Control in

India 2016. Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program. MoHFW.

Accessed September 16, 2020. Available from: www.tbcindia.gov.in

4. Raizada N, Sachdeva KS, Nair SA, et al.

Enhancing TB case detection: Experience in offering upfront Xpert

MTB/RIF testing to pediatric presumptive TB and DR TB cases for early

rapid diagnosis of drug sensitive and drug resistant TB. PLoS One.

2014;9:e105346.

5. Singh S, Singh A, Prajapati S, et al; Delhi

Pediatric TB Study Group. Xpert MTB/RIF assay can be used on archived

gastric aspirate and induced sputum samples for sensitive diagnosis of

paediatric tuberculosis. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:191.

6. Menzies D, Benedetti A, Paydar A, et al.

Standardized treatment of active tuberculosis in patients with previous

treatment and/or with mono-resistance to isoniazid: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6: e1000150.

7. Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Updated and

Consolidated Guidelines for Programmatic Management. World Health

Organization; 2018.

8. Padmapriyadarsini C, Das M, Nagaraja SB, et al. Is

chemoprophylaxis for child contacts of drug-resistant TB patients

beneficial? A systematic review. Tuberc Res Treat. 2018: 3905890.

|

|

|

|

|